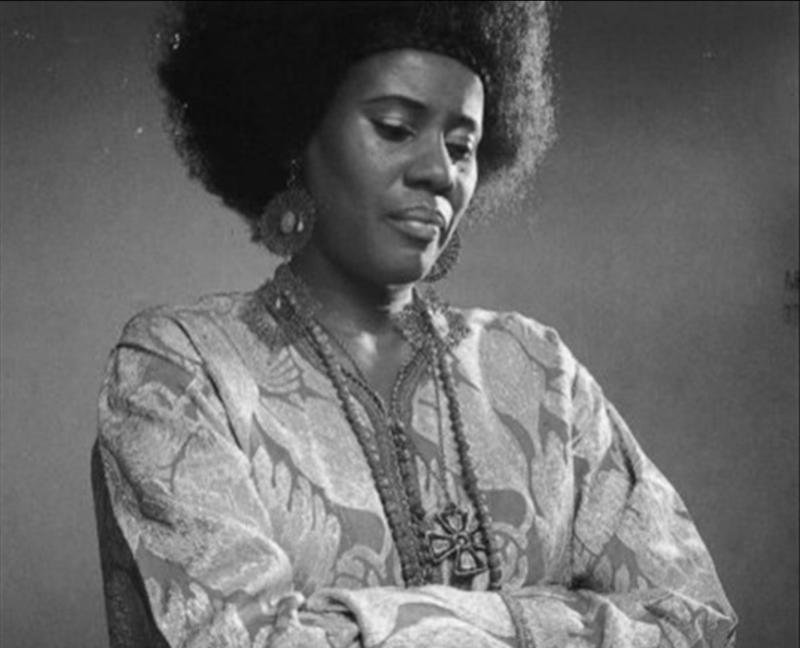

Iconic at 50: Alice Coltrane's 'Journey in Satchidananda'

( Youtube / Youtube )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC and that is Alice Coltrane's Journey In Satchidananda. This summer we're looking at, or rather listening to some iconic albums that turned 50 this year and digging into the political and social context in which they were made and their impact on both music and culture. The music historians say, 1971 was a particularly important year. Joining me now to talk about Alice Coltrane's Journey In Satchidananda and how it was shaped by its time also why it's gaining popularity now more than ever is Andy Beta music writer whose byline has appeared in the New York Times, Rolling stone, The Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, NPR, and more. Thanks for doing this Andy. Welcome to WNYC.

Andy Beta: Happy to be here, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start really basic. Some listeners might be asking themselves, Alice Coltrane, any relation to John Coltrane, the legendary jazz composer, and saxophonist? Let's begin with a little background on, yes John Coltrane's spouse. Can you give us a brief introduction to her life up until she met her husband, John Coltrane?

Andy Beta: Yes. Alice Coltrane was born Alice McLeod in Detroit in 1937. She started her career playing the piano and organ in a local Baptist church. It's probably a little bit lost the time but after the war, Detroit was the industrial center of the country and it was also a bebop hotspot. You had Donald Byrd, Yusef Lateef, Elvin Jones, Cecil McBee, and a lot of other jazz players all came out of Detroit's hometown scene. Alice's own family was a musical family. Her mother played in the church choir. Her sister, Marilyn went on to become a songwriter at Motown and her half-brother Ernest Farrow was a prominent jazz bassist in the city. She took up piano and organ at an early age and started playing these churches in the city and experienced what she called the gospel experience of her life. Very formative, early experiences for her.

As she grew up, her half-brother encouraged her to keep at it. She kept playing jazz, played bebop, married a Scott singer, and moved to Paris where she was mentored by another bebop, a legend, Bud Powell before her marriage ended and she wound up back in Detroit, which is where she joined a vibraphonist there by the name of Terry Gibbs and they began playing in Detroit. They landed this gig opening for the John Coltrane Quartet in 1963, soon after that, John and Alice were together.

Brian Lehrer: Did John and Alice Coltrane record together before his death in 1967?

Andy Beta: Many times. At this point in time, the John Coltrane Quartet was one of the most beloved jazz bands working at that time. By 1965, the pianist McCoy Tyner, and drummer Elvin Jones left the group. Soon after, Alice took over the role as a pianist in the band.

Brian Lehrer: Despite the ethereal sounds of harp and saxophone that we heard in the intro to the segment, and we'll play a few more track excerpts from Alice Coltrane's Journey In Satchidananda as we go, despite those ethereal sounds of harp and saxophone from that title track and in the whole album, it was born out of grief we should say. John died of liver cancer in 1967. According to an article in Pitchfork, the story goes that John Coltrane had ordered that harp, but died before it could arrive. Could you elaborate on that story a little bit for us and the role of the harp on this album? Not an instrument you hear in jazz a lot.

Andy Beta: Right. It's very much an album without a lot of history in the form. I guess it should be known that in the 1960s, John Coltrane was like many people in America. He was a seeker, he was reading the Bhagavad Gita, studying meditation, yoga. He was very much of that time and his sound began to change dramatically as he was pushing towards something that wasn't jazz, that wasn't necessarily blues that could somehow embrace Indian classical North African music. He called it a universal sound and he himself didn't live to realize this and that became Alice's mission. The Coltrane house itself, he had a drum kit. He was studying with wooden flutes and he was always trying out new instruments.

Most famously he picked up the soprano saxophone and learned that and that became the instrument he used on his biggest work, My Favorite Things. I think it's something along those lines that led him to order this heart for his wife. As you said, harp is [unintelligible 00:05:34] sounded jazz without much precedent. I imagined this gift for his wife was pushing forward his new sounds and new possibilities. We've mentioned that John passes from liver cancer, and it was incredibly abrupt. He complained about being in pain in May of that year, and six weeks later was gone. She was left a widow by the age of 30 with her daughter from her previous marriage and three young sons that she had with John Coltrane. Then reeling with all this harp shows up and she told Ebony magazine at the time, "I noticed that his invisible hand that brought me through." No doubt this harp arrives as this sign from beyond for lack of a better description.

Brian Lehrer: That's a haunting story. I see that a few Alice Coltrane in Satchidananda fans are calling in and we'll take your phone calls in a minute. 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280, as we continue our series on important albums and music that came out 50 years ago, this year, 1971 considered an unusually important year in music and their social context today. It's Alice Coltrane's Journey In Satchidananda with Andy Beta, music writer whose byline has appeared in the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, NPR, and more. 646-435-7280. Before we take a few calls and hear some more music excerpts, if there's a reason why people might not be so familiar with Alice Coltrane as compared to John, even though her popularity is rising these days so long after her own death, you wrote in a recent article in the Washington Post that in jazz circles, Alice Coltrane was maligned and disparaged in a manner that I guess we could say anticipated the vitriol that would be dumped on other spouses of beloved male rock stars, like Yoko Ono and Courtney Love. Can you talk about why critics were so harsh toward her solo work at first?

Andy Beta: At the time, the Coltrane Quartet was one of the most beloved jazz groups of the time. They were just formidable, nothing could stop them and they made so many classic albums. Then you see this break up with McCoy Tyner leaves, Elvin Jones leaves for one reason, or the other, this blame is put on to Alice. She's the reason they broke up and it very much parallels the idea of, "Oh, it's Yoko Ono that breaks the Beatles." The Beatles couldn't break up on their own, it had to be this outside force, this woman that comes in and she's the one that makes the break up possible. I just think there were just these other elements where obviously Coltrane himself was undergoing these changes.

Instead of imparting it onto him where John Coltrane himself is almost a sainted figure in jazz and in 20th-century music. If he can do no wrong, then who is to blame for this? Unfortunately, it becomes Alice because, with his passing, Alice has control over the tapes and all the recordings he made in the years leading up to his death. As some of this music starts to come out posthumously, there's these other elements that she adds to these tapes. [unintelligible 00:09:30] this album called Infinity, where she adds in another bass player, Charlie Hayden, who played with Ornette Coleman and she had strings and these other things, and which is basically heresy in jazz. Overdubbing is frowned upon, adding these things after the performance is greatly frowned upon so she just dealt with criticism for her own work and then for how dare she add these element's to John Coltrane's music?

In 2002, she addressed these criticisms in an interview with The Wire magazine where she was just saying, "Here's all these people saying, "We know that the original recording didn't have any strings, so why didn't you leave it as it was?" Her response was, "Were you there? Did you hear John's commentary and what he had to say?" Goes on to say, "We had a conversation about every detail. John was showing me how here, these are the sounds, blends, tonalities, and resonances. These things could all be in there." As she argues, she was actually carrying out his vision by bringing these other elements in and taking his music to places that where he to live, he probably would've done it himself. This became her role, carrying the torch of his vision forward and the slings and arrows that she faced because of this.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting and important historical context there. Who gets to play the role of saxophonist after the death of her husband John Coltrane on Alice Coltrane's classic Journey in Satchidananda? It's Pharoah Sanders. Let's listen to just a little bit of his playing on the song from the album Stopover Bombay.

[music]

Jeanine in Northern Virginia, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jeanine, thank you for calling in.

Jeanine: Hey, Brian. I just wanted to say thank you so much for featuring this Alice Coltrane. She is amazing. Throughout COVID, one of the many things I do as an artist, I'm a conscious dance facilitator, my form that I share is rhythm therapy. I was prepping for an online class because I've taken my classes online early on in the pandemic and I found this through Spotify. It's just helped me through this whole year, finding a Black hippy, an old-school Black hippy [chuckles]. I was born in 1970, so I was one when this came out.

It's like finding her was like finding a friend that I never knew existed because now there's been an upsurgence of Black folks doing yoga and kinetic yoga and connecting to the African roots of yoga and spirituality in that way. This music just blends the American form of jazz with ancient forms, with the harp, and with African rhythms in such a way that during all of the chaos of COVID and last year with all of the social justice stuff and George Floyd, just to be able to lean into this music was a way that my mind and a lot of my students' minds were able to rest. Thank you for featuring this, and thank you to the expert for giving more perspective about Coltrane, about the couple, about their kids. I just want to thank you so much. I lost my mom on the 11th, and literally, I was listening-

Brian Lehrer: Sorry.

Jeanine: -to this as part of my healing. Music really does make a difference. Thank you for featuring this.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you.

Jeanine: I hope that more folks will listen. [laughs]

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Jeanine. Thank you.

Jeanine: Have a great weekend.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you so much. Wow.

Andy Beta: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Andy, first, Black hippy, do you second that description of Alice Coltrane from back in the day? What about her rising popularity now? More family context, her son Ravi Coltrane is a well-known jazz saxophone player these days. The producer and rapper Flying Lotus is her grand-nephew worked with artists like Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, even Kendrick Lamar. There's I think hip hop-influenced spiritual jazz music that's the context for which Alice Coltrane is making a posthumous comeback. What can you say about any of that?

Andy Beta: Just speak to Jeanine's point and whether I would call her a Black hippy, what she and John were doing definitely predates the rise in hippydom. One could argue that John Coltrane's example inspired these other musicians in rock to take on this expanded consciousness and to learn more beyond western civilization and western history. The era we're talking about is very much about upheaval and the social ills of the time. Along with John Coltrane, jazz became more fiery, more chaotic, more angry.

You also had artists like Abby Lincoln and Nina Simone who were growing more and more politically outspoken. Also, someone like Marvin Gaye, who's What's Going On also comes from the same time. Really tackling these ills and these issues that are still present with us, police violence, war, poverty, inequality, drug abuse, death. Obviously, as we've seen in the last year or two, these ills are still with us and very much still a problem in our society. For many people who went through the last year and a half, it's like, what do you do about it?

What's crucial for Alice is she turned inward. You can call it in today's parlance it's, oh, it's self-care, it's spiritual self-preservation. Amid all of these, Alice was seeking a higher wisdom. Everything around her is angry and engaged and here she is in this way that would just be really baffling at the time. It's introspective, it's contemplative, it's gentle and impressionistic. I think a lot about Christ's message in Luke 17:21 where it says, "Behold the kingdom of God is within you." Journey in Satchidananda is that exactly because when you think about taking a journey, you think about you're going somewhere, you're traveling. You're visiting something. Just in the name itself, it's Journey in Satchidananda. It's this inward journey that she's taking in the music.

Brian Lehrer: It's in it's not to. That by itself is so interesting. She had her Journey in Satchidananda. George Harrison at that time in the middle of all of the things that were swirling around him as a member of the Beatles turned to similar kinds of spirituality. Let me get Kathleen in Jersey City. Kathleen, I apologize for having to crunch you but 30 seconds. I know you're calling in about Satchidananda.

Kathleen: Oh, yes. I was trained at Integral Yoga on 13th Street in New York City. I was told there was a time when Integral Yoga was petering. There was a need to raise money to purchase the building in order to continue the work Satchidananda was doing. It just so happened that he decided he was going to purchase the building and they needed so much money. It just happened that Alice Coltrane called up and said, "I want to donate this amount of money." It was the exact money, exact sum that he needed in order to purchase the building.

Brian Lehrer: The last track we're going to listen to a little bit is the live recorded Isis and Osiris, going out on this segment, but on it, listeners, you can hear Vishnu Wood playing the oud in the minor scale. It's one of the songs on the album that sounds the saddest. We've talked so much about grief in the context of Alice Coltrane's Journey in Satchidananda. We thank Andy Beta, music writer whose byline has appeared in The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, NPR, and more. Wrote about the Alice Coltrane album in the Washington Post. Thanks so much for coming on, Andy, this was really interesting and moving.

Andy Beta: Thank you so much. It was an honor to be here.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.