Education News Roundup

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. This is school vacation week and we thought we'd offer some calling time now to teachers and principals and other educators out there today, which should also be interesting for everyone else. We've started a Twitter thread for those of you who don't want to call. It says, teachers and other educators, fill in the blank. After two pandemic years, my students are more, fill in the blank, than in 2019.

Teachers and other educators fill in the blank, after two pandemic years, my students are more, blank than in 2019. Tweet a reply using the #pandemicEd or call us up to answer on the air at 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Again, teachers and other educators, fill in the blank. After two pandemic years, my students are more what than in 2019. 212-433-9692. I wonder if one of the words some of you choose to fill in the blank is the word missing.

There are these stories of declining enrollment, at least in the New York City schools, and a new debate over whether schools that now have fewer kids should get less money from the city, the usual formula, I think, is X dollars per child. We'll talk about that. Complete the sentence however you want, teachers and other educators, fill in the blank. After two pandemic years, my students are more what than in 2019? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 or tweet a response using the #PandemicEd.

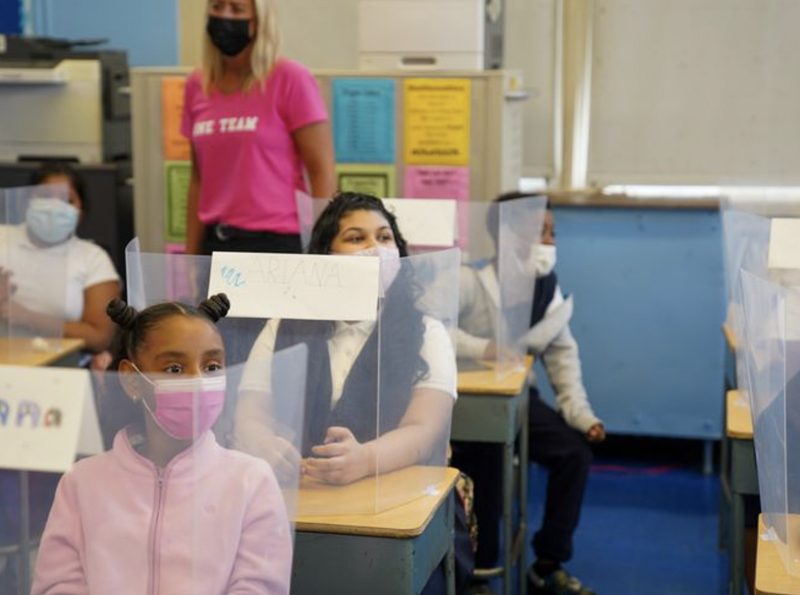

Also, when you call, we can talk about what else you're thinking about that's teaching-related as you get this much-needed week off. With state-level mask mandates coming off, what would you do in your classroom about masks if you get the autonomy to decide at the classroom level?

With state-level mask mandates coming off, you don't necessarily get to choose, but what would you choose in your classroom about masks if you get the autonomy to decide at the classroom level? 212-433-WNYC? Is it your observation that long-term masking has harmed any of your students in any way? What's your classroom-level view of that here on February 21st? 212-433-9692. How are you feeling about your own protection as adults in those classrooms?

Teachers, are masks still an issue for you as they pertain to you, not only the students? 212-433-9692. For those of you in New York City, I'm definitely curious to hear if you think the Eric Adams' administration, including David Banks as Schools Chancellor, are making a difference in your school in any way for better or worse or next or whatever or is it just too early for that? 212-433-WNYC. Teachers and other educators, fill in the blank. After two pandemic years, my students are more what than in 2019. We're filling the blank on Twitter, see our tweet, asking the question, or just reply with the #PandemicEd.

Along for the ride on this is Daily News education reporter, Michael Elsen-Rooney. Hi Mike, thanks for joining us on what maybe should be a school holiday for education reporters too. Welcome to WNYC.

Michael Elsen-Rooney: Thanks so much, Brian. Good to be here.

Brian Lehrer: Would you like to play predict the response on our fill-in-the-blank? Not what you would say but what words do you think we might hear from teachers and principals and other educators? After two pandemic years, my students are more what than in 2019? Based on your reporting.

Michael Elsen-Rooney: I'll give it a go. I thought there may be some responses along the lines of, my students are more energetic or emotional or rambunctious perhaps. Which I think is just a reflection of kids have been through a lot over these past two years, and there's just some adjustment in coming back to school and getting used to the routines and the rhythms of being in school again. For some kids who were fully remote during the pandemic, just sharing a physical space with other kids again, that all takes some time to iron out.

I thought maybe on the more positive side too, there could be some responses in the bucket of, my kids are more resilient, or my kids are more tech-savvy, or my kids are more mature, is a reflection of teachers have seen in this new up-close way, all of this stuff their kids are going through, and balancing jobs, perhaps, or helping siblings. They've gotten some new appreciation for that, I think too.

Interviewer: Teachers, are any of those words the ones you would use to fill in the blank on your students are more what than before the pandemic? Mike put on the table, resilient, rambunctious, mature, tech-savvy. How about for you? Kate in Yonkers, you're on WNYC. Hi, Kate.

Kate: Hi, Brian, how are you today?

Brian Lehrer: Good. You're going to fill in that blank for us?

Kate: Yes, I am. Yes, I am. While I liked all the other adjectives that were just put out, one of the word I would use would be underserved. I wish that I could say that in 2022, that my special education students and general education students had more support. Mostly what we've seen is just an increase in testing. There's a lot of testing for the children to sit through, and I have to tell you that fourth graders are sitting through tests with 53 questions for two hours, so we've already done this four times.

That is something that I wish that the United Federation of Teachers could be a little bit more vocal and advocate more for the children, and that is what I wish.

Brian Lehrer: That's interesting. When you say there's all this testing, are you talking about in this school year, to see where the kids were after a year of going remote?

Kate: Yes. The kids, where they did this thing called the maps growth test. It was the first time that my children sat in a room with a laptop and had to answer 53 questions in two hours. That was very hard for them because most of them can figure out that maybe I'm not doing that well at this. One girl even complained, "Why are they asking me questions about things that I haven't learned yet?" It was like a humiliating process. There's going to be another round of testing and not to mention the state test.

Brian Lehrer: Is it revealing anything to you that's important, though, about where those kids are, as they come back to in-person learning? There's this phrase out there, learning loss. The tests are to measure learning loss, but a lot of people consider that phrase offensive and don't want us to say learning loss. I'm curious if you're in that camp?

Kate: I am in the camp, and it is clear that not all but some children are struggling more than other children because most children can learn regardless of the situation, but there are many children that are not. I just wanted to say, Brian, that the United Federation of Teachers, which is my union, they've had the same people in place since the 1960s. I wish that we could have perhaps a change in the Union so that the rights of children are more present today in the conversation because they're not. If they were, they wouldn't allow 10-year-olds to have to sit through all of this.

Brian Lehrer: Kate, thank you very much for your call. I really, really appreciate it. All right, teachers, you heard Kate there. You heard some of the predictions from our guest Daily News education reporter Michael Elsen-Rooney. How would you fill in the blank, your students are more what than before the pandemic? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet it with a #PandemicEd. We'll read some of your tweets as we go. Andrew in Manhattan is going to fill in the blank. Hi, Andrew, you're on WNYC.

Andrew: Hi, how are you?

Brian Lehrer: Good. Your students are more what than in 2019?

Andrew: I would say more dependent on me as the focal point to keep them together. I teach in the arts, I teach dance to my students. In my classroom, because of the nature of the classroom, I will also have them keep masks on even if mask mandate drops just because of the situation in terms of we can be more in close contact.

Obviously, they're dependent on me as a focus. Their focus is more toward me than toward each other and that their social skills towards each other is what is in detriment, and that's part of the challenge in the classroom right now.

Brian Lehrer: How do you respond to that as a teacher? How do you deal with it or help them if they're more dependent on you?

Andrew: In dance classes, I started [inaudible 00:09:52] and we go to duet work and then we'll go to group work and I've been leading up to that and how [unintelligible 00:09:59] to do with social-emotional learning, which I feel the arts teach really well and inherit in how we present it in all the arts, not just dance, but in music and theater also. We have a very strong arts school at my school, we have a lot of arts.

Brian Lehrer: You're talking about dance and you're talking little kids, right?

Andrew: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: I guess I would think pre-K. I would think [crosstalk]

Andrew: I teach pre-K through five.

Brian Lehrer: Pre-K through five. I would think that kids anywhere in that age range, after being cooped up so much during the pandemic, if they had an opportunity in a class to dance, that they would start moving like crazy, is that wrong?

Andrew: No, it's not wrong at all. They really need it. They really, really need it. We even have an after-school program, I have two dance companies, one third grade, and one fourth and fifth grade. That is the best part of my day because they come in and we're creating and are working together. I set up the rules and the classroom for them, and then we bring one piece that I'm making, and then they're going to work on their own stuff. They need that to be in contact with each other. They need to have as playful in many, many ways, but I feel like that should be part of our all system.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Andrew. Thank you for your call. Some of the tweets coming in. A listener writes, "My students are more flexible than before the pandemic." Another writes, "After two pandemic years, my students are more in need of social-emotional learning and mental health support than they were in 2019." Another listener tweets, "As a public school teacher and public school parent, after two years, we are all more distrustful of institutions and whiplashing ever-changing protocols and rules, so more distrustful."

Another one writes, "I'm a fifth-grade special ed teacher. After two years, my students are still getting back lost time on skills, but they are more aware of and engaged with the world." There's a smattering of what's coming in on Twitter. Listeners filling the blank. My students are more what than before the pandemic in 2019. Tweet @BrianLehrer or use #PandemicEd as we continue along for the ride on this with Daily News education reporter, Michael Elsen-Rooney. Michael, what are you thinking as you hear those couple conversations on the phone or some of those tweets?

Michael Elsen-Rooney: You really hear the full range of just how complicated this is and how I think schools are still trying to assess what the effect of the pandemic was on those students. It's not just this simple cut-and-dry thing. There were a lot of clear areas where students really suffered and schools are trying to identify that, but a lot of areas where kids continued to grow and how do you strike that balance in terms of what school looks like right now.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take some more calls. Erica on Long Island, you're on WNYC. Hi, Erica, what do you teach? Your students are more what?

Erica: Hi. I teach special education and co-teaching high school on Long Island. My students are far more distracted than they were before the pandemic. The phones were always an issue, the AirPods, whatever, but since they were either learning all virtually for parts of the pandemic or last year we taught in a hybrid model, where half were at home, half were in the room. When you're at home, they were learning through Google Meet, then they swap places the next day, that they are just more distracted.

The phones are an issue, having split screens open. They were used to having other things around them when they were at home to entertain them, having access to other devices to help them find the answers. It's been a struggle to get them focused and out of those habits of, I can be on TikTok and pay attention in class and I can look up the answers. That's been what I've noticed from the students.

Brian Lehrer: More distracted. Erica, thank you very much. Yeti, in Harlem. You're on WNYC. Hello, Yeti, if I'm saying your name right. Am I?

Yeti: Hi. Yes, it's Yeti. Nice to speak with you.

Brian: Yeti. I apologize. Hi.

Yeti: That's all right. Hi.

Brian Lehrer: What do you teach?

Yeti: I teach 12th-grade science but I'm also a special education teacher in a co-teaching classroom.

Brian Lehrer: Your kids are more what than in 2019?

Yeti: I feel that our kids are more lost. I feel like just like the last caller when you're in school, you have the ability to have consistency, you have the ability to have rhythms in place, you have boundaries, you have all of these things that help to fortify you as-- and these are talkers, young adults, getting them ready for the world outside because they've lost basically two years of that repetition and those qualities that help to get them ready for the outside world.

It's a struggle as well, just to get them to do basic, just to stop being on their phones as the last caller said, just to remember why they're in school to get them to do the work, to stop relying on us as much. It's a bit frustrating, it's a bit heartbreaking. There are some lights at the end of the tunnel, but it's a fight, it's definitely a fight.

Brian Lehrer: One of the questions I'm going to ask our guests from the Daily News about, has to do with graduation rates, which were actually a little up in the last school year, which might surprise people since there's all this assumption that people were falling behind. For you, as someone who teaches high school, if I'm understanding you right, did you have a better graduation rate than before? If so, what would you attribute it to?

Yeti: Unfortunately, I can't answer that question. This is my first year at this new school. Before that, I was in middle school. I will say for our middle schoolers, they were able to progress relatively seamlessly, but it's different when you get to an older group of kids.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. Yeti, thank you so much for chiming in. Michael Elsen-Rooney, Daily News education reporter, let me go to that story that you wrote recently about the graduation rate being slightly up. That might be counterintuitive if people would've thought that there would've been this falling behind and graduation rates might have declined. Tell us what you know.

Michael Elsen-Rooney: The state came out with their annual graduation rates and it showed that New York City's four-year graduation rate for this cohort that graduated in 2021 was up about two points from last year, which was up from the previous year and has actually been rising steadily for a while, a decade about. The big caveat here is that, over the past two years, they changed the requirements to graduate.

Normally, you have to pass five Regents exams, and starting in spring 2020, they canceled the Regents exams and continued to cancel most of them through the 2021 school year. Instead, they allowed you to get credit for that if you passed the course that corresponded to that class. We don't really know how much that affected things. It's certainly possible it did and so it's not quite apples and oranges. It's certainly not the sky falling type numbers.

Brian Lehrer: Some of the students who might have failed the standardized Regents exam in some of the subjects that passing the Regents is required for graduation in, they might have gotten a pass to graduate anyway. You have a related story, I guess, called New York city teachers conflicted over having to give failing students F grades again, rather than incompletes as Omicron upended learning. Did F grades take the pandemic off until now?

Michael Elsen-Rooney: Yes, pretty much. That policy came into place in spring 2020 when schools shut down. I should say, the rationale behind not giving out Fs and not holding Regents exams, is that the belief was there really would not have been a fair way to assess kids given the vast disparities and access kids had to remote learning and how do you impose a test that's really fair in those circumstances.

There are arguments against it, but a lot of real concerns about what it would've meant to do that. The F rule, these grades, basically, you got an incomplete instead of an F and had additional time to make it up. That rule expired at the start of this school year, and the idea was somewhat back to normal, full in-person in school, we can do failing grades again.

My story was about the fact that went out the window when Omicron hit and there were lots and lots of students absent again and things were totally disrupted, and so some teachers felt again, it was difficult to fairly assess which kid deserved to fail in those circumstances.

Brian Lehrer: This is [unintelligible 00:20:00] WNYC-FM HD and AM New York. WNJT-FM 88.1 Trenton. WNJP 88.5 Sussex. WNJY 89.3 Netcom. WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are New York and New Jersey public radio. Few more minutes with Daily News education reporter, Michael Elsen-Rooney on this first day of winter break and so many school districts around here Presidents' week, as some call it.

The question on the table, for you educators on Twitter or on the phones, fill in the blank. My students after two years of the pandemic are more what than in 2019. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or a tweet @BrianLehrer with the #PandemicEd. More tweets coming in, "My students are more politicized, activated, radical," says somebody.

Someone else writes another list of adjectives. "My students are more disengaged, angry, emotional, violent, desperately looking for connection." Those are almost the opposite. Michael, I don't know if you've reported on anything like this one way or another but one teacher saying their students are more disengaged, angry, looking for connection desperately. The other one says they're more politicized, activated, and radical, which indicates some engagement. Any thoughts?

Michael Elsen-Rooney: The first one made me think that it seems like such a long time ago but George Floyd's racial-justice protest happened that first summer during the pandemic. I remember talking to a lot of students who were really engaged in that and probably the fact that they were not in school contributed to that. They had more ability and more space to focus on those types of issues.

It could depend on how you're looking at it, maybe engaged in things outside of school or causes or political issues or passions that they have. Obviously, if you're looking at it in the academic sense, that could look very different and kids who engaged in things outside school had trouble readjusting.

Brian Lehrer: Speaking of engaged or disengaged, are you familiar with the declining enrollment stats in the city? Is it really hundreds of thousands fewer kids than last school year?

Michael Elsen-Rooney: I'd have to look at the exact number. It partially depends on how you're measuring cause if you take into account the fact that preschool was actually expanded this year due to the city having more federal money and they expanded the three-year-old pre-K program. Enrollment's only down about 2% compared to last year. If you remove that from the equation, it is down somewhat more significantly.

It is a real question and challenge for the city in terms of if that continues, how does it affect individual schools? If you have schools that are becoming really small, it just becomes much harder for those schools to operate. Then, as you mentioned at the top, funding is traditionally tied to enrollment and when schools lose students they lose funding.

Brian Lehrer: We've been reporting on that on the station with our education reporter, Jessica Gold, the controversy over with declining enrollments schools getting less city funding at those schools and they say it's not fair. If the usual formula is based on per-pupil enrollment, theoretically, the students who remain wouldn't get hurt by that if the per-pupil funding for each of them is the same as it was. Is that too simplistic a way to look at it?

Michael Elsen-Rooney: I think the problem is that there are certain features of schools that you just need that are not dependent on the number of students. For schools to operate, you just need certain things in place. You need a certain number of administrators and a certain number of social workers. If your budget keeps shrinking, you lose the ability potentially to provide some of those basics that just should be like a foundational thing that every school has.

I think that's the worry and schools plan around the number of staff that they have and a stable amount. If that's in flux all of a sudden and you're losing people, that just can really be a challenge to adjust to.

Brian Lehrer: One more to tweet, one more call. Fill in the blank. My students are more what than before the pandemic in 2019 and elementary school. Our teacher writes, "My students are more appreciative than in 2019." Justin in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Justin.

Justin: Hi. Thank you for having me. I would say my children are more broken if I had to pick an adjective. I would say I think a big part of it, what's going on right now, obviously, the 18 months where kids were viewed, in my view, as viral vectors and as young human beings in need of education. Kids being stuck to this ridiculous six-foot rule last year where high school kids only attend for three hours twice a week in order to maintain that sacred six-feet long after all of us.

I'm a school social worker and all educators had vaccine access. Now, again, being in-person is so much better even with masks than being home, but now it's time to get rid of the masks. Every adult recreation, you could even see our mayor and our governor partying it up and having fun maskless everywhere. Kids, four-year-olds, five-year-olds, who are with speech impediments and delays, have to mask all day, even in speech therapy, even in classes.

They were masking for two years to protect the adults. The adults are now living their lives and our kids who-- Adults, you and I, I don't know you personally, Brian, but you and I wouldn't suffer if we had to wear a mask on a Saturday night but kids do suffer from it. I really think, I really hope that the governor and the mayor take the same step as governor New Jersey over the river in New Jersey, Governor Murphy I should say, and that masks become optional ASAP.

Brian Lehrer: Of course, that's a big debate. Do students wear masks suffer? For you, as a school social worker, who says you see it, how do you see it?

Justin: The kids tell me. Obviously, some kids say they don't mind but some kids they say, "I don't know what half my classmates look like. I don't raise my hand as much in class because it's just so hard to talk with the mask," or the shy kids who had trouble making friends before COVID, now have the double whammy of being out of practice for 18 months at home, and now trying to socialize from behind the mask who can't see facial expressions.

I fear that there are some kids who they don't say anything but they're wearing the mask, not for COVID caution. Maybe they already had Omicron plus two or three shots so there's no concern about getting sick with COVID but they covered three-quarters of their face because don't like their appearance. Body image has always been an issue for adolescents. If your entire pubescent face has been covered since you were 12, 13 years old, it's become like a security blanket.

I think we're going to have a lot of it issues. Obviously, no one should ever be forced on mask. If anything, we should be providing premium KN95 masks to those who are sincerely concerned and want to keep wearing it. To normalize the idea of showing our faces and unmasking, its past time.

Brian Lehrer: Justin, thank you so much for your call. Let's end on masks. Michael, after that call like the caller reminded us, Governor Murphy in New Jersey is lifting the statewide requirement for masking in schools on March 7th. Individual school districts will decide. Newark, for one, says it will keep theirs in place. In New York, Governor Hochul says she's waiting until after this winter break week to decide. Did she say what she'll be looking for?

Michael Elsen-Rooney: She said it's going to be a combination of things, that there's really no one metric. It's vaccination rates and case rates and hospitalization rates. As we've learned, this is just a really, really sticky and difficult question. There's obviously going to be people upset no matter what she chooses. The big question, of course, for New York City, is whether the city would keep its own mask mandate even if the state lifted it. We'll have to see. She's reevaluating that after the break, is what she said

Brian Lehrer: Michael Elsen-Rooney, Daily News education reporter. Thanks so much for joining us today. Really, really appreciate it.

Michael Elsen-Rooney: Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.