The Economic Disconnect

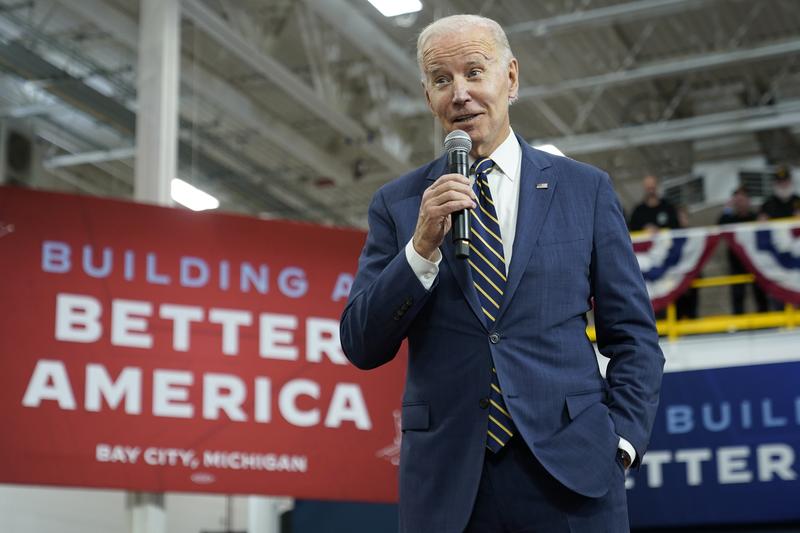

( Patrick Semansky / AP Photo )

Brigid Bergen: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. I'm Brigid Bergen, senior reporter in the WNYC in Gothamist newsroom, filling in for Brian today. On today's show, we're going to talk about the financial challenges of caring for our elders, and how the elder care system here in the United States is a disconnected Patrick that really doesn't work for anyone, and we'll want to hear your stories. Plus, now that the sag after and writer strikes are over, is it back to work for our local film and TV workers?

We'll talk about that sector of the economy. Have you ever looked around at other people and thought, they seem to have it all figured out? They are the real adults, and felt like you're just a fake it till you make it adult, yes, we have too. [chuckles] We're going to talk about that feeling of adult imposter syndrome later in the show. First, we turn to the economy. As a country, we were on the precipice of major uncertainty again, a looming government shutdown just before the holidays, and in one bright spot from an otherwise really weird day in Congress, we will talk about the almost fist fights another time, House members passed a stopgap measure to continue funding the government.

Speaker 2: On this vote, the yes are 336, the nays are 95. Two-thirds being in the affirmative the rules are suspended, the bill is passed, and without objection, the motion to reconsider is laid on the table.

Brigid Bergen: By all accounts, that is very good news for the economy, a major source of uncertainty is off the table, but will that help bolster the moods of Americans in terms of how they feel about their personal finances? It's too soon to know for sure, but there's definitely room for improvement. Of all the takeaways from the New York Times Sienna College poll released last week, more than half of those polled said that Biden's policies had hurt them personally. The Federal Reserves recently released Survey of Consumer Finances, however, paints a dramatically different picture.

Comparing American's net worth and income to that of three years ago, Americans in every income bracket saw sustainable gains in their net worth. If the economy has been improving post-COVID, whether as a result of President Biden's policies or something else, then why don't Americans feel that way?

Joining me now to talk about that gap between the mostly positive economic indicators and how Americans perceive the state of the economy is James Surowiecki, a contributing writer for The Atlantic, and the author of The Wisdom of Crowds. James, welcome back to WNYC.

James Surowiecki: Thanks for having me on.

Brigid Bergen: Our listeners, we can take your calls on two tracks here. The numbers from the Fed show that many Americans have grown their net worth in the last three years. Some bought houses, some started their own businesses, some paid down pre-existing debt when student loans were paused or the child tax credit was in place. Are you one of those people who has benefited from some of these programs, and how have you grown your net worth? Give us a call at 212-433-WNYC, that's 212-433-9692. You can also text or tweet @Brian Lehrer.

As we've seen from those polls, a lot of Americans feel that they are worse off than they were three years ago. If you feel that way, we want to hear from you too. Do you feel as some told the New York Times that Biden's economic policies have hurt your finances? If so, how? We want to hear from you. The number again is 212-433-WNYC, that's 212-433-9692. Is it the sticker shock at the grocery store, or are you feeling the squeeze now that student loans are in repayment. We want your help reporting this story. Give us a call, 212-433-WNYC, that's 212-433-9692. As I said, you can also text at that number.

James, now that we've wound that up, let's talk about your latest piece in the Atlantic. You looked at the numbers from the Federal Reserve's survey of consumer finances, as I mentioned in the intro, it shows that Americans in every income bracket saw substantial gains with the biggest gains registered by people in the middle and upper middle brackets. Where, or maybe how is net worth growing for middle and upper-middle-class Americans?

James Surowiecki: The survey of consumer finances, just a little bit of background is a survey that the Federal Reserve does every three years. It only comes out every three years, and it's really detailed. They have this professional survey company look at, interview people, and really go in-depth into people's net worth, their income, the whole thing. This particular survey was done and because of that, it takes a long time.

What this survey looked at was people's net worth, their home balance sheets as of 2022, and they compared it to 2019, which was right before the pandemic, and was the last time that the survey had been done. As you said, what they found was that pretty much across the board, Americans in every income bracket or wealth quintile, whatever you want to call it, saw gains, the biggest gains were for people in the middle and the upper middle, like the 70% to 80%, 90% of the income spectrum.

I think that the biggest source of those gains predictably, was the increase in the value of people's homes which was very impressive. That's almost by definition, most Americans their homes are their biggest asset, [chuckles] for a lot of Americans, it's almost their only asset. The increase in home values translated into a very large increase in their net worth. We also saw increases in people's financial assets. In part, that's the stock market, but the amount of money people had in the bank went up as well, people paid down debt.

One thing to keep in mind is that these numbers are all median numbers. They are really looking at, it's not just, oh, well, a few people at the top did really well, and that's skewed the whole thing. When you look at the median net worth of literally the average American, it rose by something like 37% between 2019 and 2022 which is a substantial gain.

Brigid Bergen: Yet, the New York Times Sienna College poll was getting a lot of traction in the media this past week. Other recent surveys show much of the same. Only 21% of those surveys said that their finances had improved under Biden's presidency, that's according to a bank rate poll, 33% surveys said that they were actually worse off financially under the Biden administration, that's according to an ABC News Washington Post poll. What specifically do you think Americans are reacting to, James?

James Surowiecki: I think the simple answer is inflation. You mentioned the sticker shock at the grocery store, and I think that is the primary driver of the way that people feel about the economy, gas prices as well, even though gas prices have been relatively stable now for a year or so. They're still significantly higher than they were certainly when Biden took office, and certainly than they were at the bottom of the pandemic in 2020. I think it's really that. We just don't have that much experience with inflation for a lot of people, it's really been literally decades with the exception of a little spike in 2006, 2007. It's really been decades since we've had what felt like significant inflation.

I think people were shocked by it, almost literally, I think that that's the biggest thing. The thing that's striking about it is that, the reality is, the net worth thing, the survey of consumer finances, that's the value of people's homes went up or whatever and you could say, that's not real money, it's hard to tap it or whatever it is, but real wages for the vast majority of Americans are now higher than they were in 2019. Even when you take inflation into account, the wage gains people have enjoyed have been substantial enough that something like 80% of Americans actually have higher real wages than they did in 2019.

I think that the reality is that, the inflation that people see and feel, has just been really so powerful that it's overshadowed everything. Consumers have actually felt better about the economy or they were feeling better [chuckles] about the economy between May, 2023 and September, then the last two months for whatever reason, they've gotten gloomier again. If you go back to, say, middle of 2020, '22, which is when inflation was really high, real wages had not fully recovered, Americans were more depressed about

the economy than they were at basically near the bottom of the global financial crisis in 2009. [chuckles] The economy was in a lot better shape in 2022 than in 2009-

Brigid Bergen: Sure.

James Surowiecki: -but inflation was high and it just bumped people out.

Brigid Bergen: James, have you dug into the data from any of these polls in terms of how this dissatisfaction breaks down, say, between income brackets or even party lines? Is this a case of richer Americans being dissatisfied with government spending on programs, or is it more complicated than that, or are there some partisan issues that are driving how people feel about the economy?

James Surowiecki: There are certainly partisan issues and that has been the case in polls now for many years. Republicans in particular feel much worse about the economy when a Democrat is president and much better when a Republican is in office. The best example of this was that [chuckles] if you looked at people's attitudes toward the economy in January 2017, so December 2016 or whatever, November 2016 to January 2017, so right after Trump got elected. Before the election, Republicans were incredibly gloomy about the economy, and as soon as Trump took office, their perceptions of the economy spiked massively.

Obviously, nothing had really changed about the fundamentals of the economy, but their feelings about the economy had grown significantly better. The same was true in November 2020 and then January 2021. Partisan attitudes do matter a lot and Republicans are significantly gloomy about the economy than Democrats are. Having said that, one of the things that is striking is that even Democrats have not been as cheery about the economy or even just feeling okay about the economy as you might expect. Even Democrats, a high percentage of them have been feeling not so great, and independents have been quite gloomy as well. Partisanship clearly matters, but it doesn't explain it all.

On the income front, my perception is that just looking at thinking about some of these polls, there is actually isn't a huge spread. I actually think one of the things that's quite striking that we could talk about is that the last few years have actually been worse for people at the top of the income spectrum, or let's say the kind of like 80 to 95% of the income spectrum than people at the bottom. I actually think that does have something to do with the general negative vibe in the economy. I think that that actually does have an impact even though it maybe doesn't always quite manifest itself in the polls.

Brigid Bergen: I want to bring in some of our listeners to this conversation. Let's go to Janice in Soho. Janice, thanks for calling the Brian Lehrer show.

Janice: Hello, thanks for taking my call. Yes, I just wanted to add on that. I actually work with a lot of people who are very well set up, financially, and there seems to be nothing destroying their amounts of money in their bank accounts. I also think that it's in a lot of people's best interest to have what I call, they're doing a selective fake news aspect of this, so they don't want anybody else to think that the economy is good. Your guests address some of this in the previous comments.

It's in a lot of people's best interest to create this idiotic concept that there's been nothing good happening in the economy through COVID and since COVID. This report came out, it is rock solid and they're still treating it like they treat everything else as fake news. Thank you for giving me some time.

Brigid Bergen: Janice, thanks for your call. James, I any reaction to Janice's comments on this idea of how we talk about some of these reports? Is the narrative part of what is influencing how people are feeling about it?

James Surowiecki: Yes, I think the media narrative has actually had a big impact on the way people feel. There've been a variety of polls or surveys that show that people will actually say things like, they've heard twice as many stories about unemployment rising as about job creation, which makes no sense. If you think about how many jobs have been created since January 2021, and even since January 2022, even after all the pandemic losses had been recovered, it makes no sense. You'll sometimes see polls where people will say things like [chuckles] unemployment is near a 10-year high or whatever, which unemployment is still below 4% and has been as low as 3.5% this year.

I do think there is a media ecosystem that for whatever reason, and some of it is partisanship, let's say whatever that's, let's call it the Fox News phenomenon or whatever but it's not just that. I do think there is a media ecosystem that for whatever reason has been built a little bit on negativity and gloom. One of the examples I talk about in a, not this piece that I wrote for the length, but one I wrote, I've written about this subject a few times, I think because it's so striking that I wrote about a few months ago is a New York Times headline that it was sort of a report on a really good jobs report.

It said something like, "The economy doing well," blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, but then it said, "As fears linger." That was actually the second time that New York Times had used the phrase, "As fears linger," in a headline about the economy in less than a year. It just felt like a symptomatic thing that there is always this sense. If you look, whatever, last month we got the third quarter GDP numbers and the economy grew at 4.9% in the third quarter, which is crazy this long into a recovery. Yet even then, there was, but what's the dark side of it? There's really been a real hesitancy to accept that the economy is not doing by any stretch of the imagination perfect, but it's actually pretty good.

The other example of this that I have talked about is last winter, Bloomberg ran a piece that said, it has this forecasting indicator and it said, "Chance of a recession, 100%." That was another example of basically just the expectation is that things are going to go bad. That I think partly explains why people are seeing everything through whatever the opposite of rose-colored glasses is, I don't know, black-colored glasses. I don't know what the difference is.

Brigid Bergen: Some sort of bleak shade. Listeners, if you're just joining us, I'm Brigid Bergen in for Brian Lehrer today. My guest is James Surowiecki, a contributing writer at the Atlantic, and author of The Wisdom of Crowds. We're talking about the state of the economy and how people are feeling about the state of the economy. There are reports out that show that people's net worth has grown in recent years. We're asking, what are your experiences, what are your stories? How is your bank account doing under this current administration?

We also know that inflation is a real issue, and we want to hear from people on both sides of the spectrum. The number is 212-433-9692, that's 212-433 WNYC. You can also text, we've gotten in some really great texts. I'll read some in the moment, but first I want to go to Joel in Clifton, New Jersey. Joel, thanks so much for calling.

Joel: Hey, how you doing, thanks for taking my call. Basically, I just wanted to explain my testament basically pretty much. I've been one of those that were part of the great resignation. I was getting paid under 100,000, and then during this administration, I finally got my first over $100,000 job. My wife is also making close to 200. We've been seeing gains. Yes, there is inflation of course, but all this negative feelings about the economy being perpetrated by the media, I feel like they don't tell the other side of the story of people actually seeing gains and seeing their net worth rise. I don't see that too much. All I see is a lot of negativity permeating the airways and the media.

Brigid Bergen: Sure. Joel, can I ask you, what industry are you in?

Joel: I work for pharma, like for biopharma, pretty much, so anything pharma-related. My wife is a web designer and we've seen our income grow from the last previous administration, we've seen it doubled up.

Brigid Bergen: Joel, thank you.

Joel: Like I said, I'm the other side of the

other talking.

Brigid Bergen: Yes, absolutely, and you're exactly some of the people we want to hear from today. We want to, to the extent that we can, help if it is, debunk the myth that everyone is doing poorly when we see reports of numbers that indicate otherwise, and stories like yours help us do that. We appreciate you helping us report the story. I want to read a text that we received, James. A listener writes, "I feel both. I'm paying on recent Parent PLUS loans, but our older student loans were forgiven. We've had raises, but inflation sucked most of that away. We've been able to do some repairs, but that means we've taken on some debt.

I like some of what the government has been doing, but I don't understand how Biden gets the credit or the blame. I feel that corporate practices are more central to our problems, not the government." James, any reaction to both Joel who has the good news story that we are asking people to share, and then also the texter who seems to be sitting on the fence of it?

James Surowiecki: Yes. I think both of those seem like good descriptions of people's experiences in this economy. What Joel said, the thing he mentioned was the great resignation, which I think means that he switched jobs. People who have switched jobs over the, say, last two years, which is something that's happened a lot, those people in particular have done exceptionally well.

One of the great things about tight labor markets, which we have had now for roughly a year and a half, maybe two years, a tight labor market is unemployment is low, there's a lot of demand for labor on the part of companies, and as a result, what has happened? Companies have had to pay more for wages. You can see that especially for lower-wage workers. There's been tremendous demand for them, and it's translated into higher wages and actually higher real wages, that is to say, even after you take inflation into account. I think that is a reality for a lot of people in this economy.

On top of it, there's also, to me, in some ways, the most important aspect of the last couple of years is just that so many jobs have been created. We're pretty much back to where we were in 2019 in terms of not just the unemployment rate, but also the labor force participation rate. Like I said, that is really translated into gains for people at the lower end of the spectrum. We actually have seen a pretty significant reduction in income inequality at least as measured between the gap between the people at the 90% place at the spectrum, and people at the 10%. That's really compressed a lot, and I think that's really good.

Brigid Bergen: True.

James Surowiecki: The second, the texter, that I think is also true. The one thing I'd say is every time I write about this or talk about it or tweet about it people are understandably like, "Come on. Look at what gas prices are, look at what the grocery prices are," and I feel it. [chuckles] We went shopping the other day, and it's definitely the case. You come away, and you're like, "Wait, how much is it," and I totally understand that. It does feel like the wage gains or salary gains, they've gotten, it feels like, where did they go? If I'm making so much, why do I have to spend so much? Why am I not able to save more? I totally understand that.

I also think there's a psychological aspect to this that's interesting, which behavioral economists have talked about, and that is that when people think about the economy, and they think about their own financial state, and they think about raises they get, so the people who've gotten raises, pretty much everyone has gotten a raise with the exception of a few industries, which we could talk about that also, but when you get a raise, people tend to say, I deserved that. I got that raise because of my good work, because of what I'm doing blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. When inflation goes up, that, of course, is just the macro economy or it's Biden's fault or whatever.

The reality is that while your raise does have something to do with you, it also is a reflection of these broader macroeconomic trends a lot of time. It's a reflection of the fact that when companies really have to hire workers, they're going to pay more for workers, but we don't tend to think of it that way. It's like, the inflation is the fault of whoever, but the wage gains are basically your responsibility only. I think that has something to do with why people feel so gloomy as well.

Brigid Bergen: I want to bring in another caller who I think has some questions about whether these polls really have enough nuance to them. Anna in Westchester County, thanks so much for calling The Brian Lehrer Show.

Anna: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. Actually, I'm an English teacher and what we teach students in grammar is about frequency, what is the percent too much or too little you agree with this question? I think that's where I'm finding an issue with polls, which I believe generally are yes or no answers. Do you feel good about the economy or what have you? I think if the polls were done differently, there would be an algorithm where maybe 10% of the public agrees with this statement or 90% doesn't. I think that's really getting lost.

Generally, the default of the public is to complain or not really have recognition or gratitude. It's always groveling, "That's not enough, and I need more." I think that's a lot of issue where people are directly blaming Biden, I'm a Democrat, for things like inflation for which he really doesn't have a direct control. I think particularly the MAGA Republicans are generally put in a posture of outrage, loudness and complaints.

They get attention because when people raise their voice or say incredibly terrible things, that gets a lot more of the news cycle and filters into the public perception of the world compared to perhaps maybe a Democratic candidate or a posture that's a little bit more forgiving and understanding. Just as an aside, I've invested in the stock market in the past five years. My investment has grown anywhere from 100% to 300% within five years.

Brigid Bergen: Wow.

Anna: I feel a little bit stupid in a way because I'm in my '50s, where why didn't I invest earlier in my life, in my '20s, and I would have a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow?

Brigid Bergen: [chuckles] Anna, thank you so much for your call. James, just briefly, any reaction to Anna before we go to a break?

James Surowiecki: Yes. A lot of these polls do have some nuance in a sense of, they will ask do you totally agree with or somewhat agree with or are neutral about that. If you dig into those numbers, there's obviously more nuance. Even given that you're still going to see, it's still surprising. The poll result that you alluded to that I was really struck by was the New York Times, Siena poll where 53% said Biden's policies had hurt them personally.

Having said that, this point about negativity or venting, I do think some of what's going on in these polls is people are just dissatisfied generally with the state of the country, with maybe the political discourse, with just the vibe in America. I do think that some of what is being expressed in these polls has to do with this general sense of discontent, not just about inflation or whatever, but I'm just unhappy.

The thing that's really striking about these polls and that you need to think about when we try to understand them is that people feel so much worse today than they did in 2019, even though objectively the economy is in just as good a shape, maybe even growing a little bit faster, and as the Fed survey suggested, people's finances are generally in a better position, et cetera. The question is, what's changed? Why do people feel so much worse? Again, I think inflation has something to do with it or a big part of it, but I also think some of it may be post-pandemic, just a general discontent with how things have gone over the last three years.

Brigid Bergen: Sure. I'm Brigid Bergen in for Brian Lehrer today. We need to take a quick break. My guest is James Surowiecki, a contributing writer at The Atlantic and author of The Wisdom of Crowds. We're talking about the economy and how you feel about it. We'll take more of your calls after the short break. Stay with us.

[MUSIC - Marden Hill: Hijack]

It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. I'm Brigid Bergen in for Brian today. We're speaking with James Surowiecki, a contributing writer for The Atlantic and author of The Wisdom of Crowds. James, we have a board full of callers and we've been getting a ton of texts. I want to read a few of them and give you a chance to respond. A lot of people echoing the sentiment that the media is driving a lot of this narrative, that in fact they think

that the economy is doing better. One listener writes, "I believe that the economy is showing that many of the economists' assumptions and models are being proven wrong, but they have to hold on to their erroneous theories and models. One example is that higher wages are bad for the economy." I'm not sure if that person suggests that higher wages are bad for the economy.

One that I thought was particularly interesting was related to people's 401(k)s. This listener writes, "I think 401(k) accounts have taken a beating this year, especially on securities. Seeing those balances decline, affects one's perception of wealth." Any reaction to that idea that some of this is this idea of what your future wealth may be impacted by what's happening right now?

James Surowiecki: Two things. One is the stock market has actually had a very good year. Last year was grim, 2022 was really grim, but the stock market in 2023 is now up. I don't know, it's around 15%, 16% from the beginning of the year. I think since Biden took office, it's up, probably around that. I can't remember exactly what it is, but I think it's somewhere between 15% and 20%.

I do think that if anything, and the stock market had, again, was up 2% yesterday. It's rallying because the inflation number came in so low, I do think that if anything, that should probably translate into maybe better consumer sentiment numbers going forward. We'll see how that goes. I think, again, [chuckles] there's this legacy of last year, when the market was down, and people got bummed out.

The media thing is interesting to me because, one thing I would say is, so one response you'll sometimes get when you talk about this stuff is people will say, "Just look around." My point is actually like, "Yes, look around. Go to the mall, or go to the airport, or go to the supermarket, and you will not see empty aisles, and you will not see empty airports. You will actually have seen over the last eight months packed stores and packed airports and people spending a lot." That actually has been one of the big drivers for me of thinking about the fact that the economy is actually doing well, just quite concretely.

Brigid Bergen: Sure.

James Surowiecki: I know what a recession looks like. I know what it looks like when people are really feeling bad. What happens is people cut back significantly on their spending, and they are not doing that. That's why I think there is something about the way the story is being covered that does have an impact.

Along those lines, I think one thing that's worth thinking about is that, if you think about the industries that actually have not done great over the last couple of years, they include finance to a certain extent, they certainly include tech, which had a very hard time in 2022, and the beginning of 2023. You'll remember we had those bank failures, the Silicon Valley Bank failed in early 2023, the startup economy had to roll back a little bit, and the media business. We know we're wrestling in the media business with a tough advertising market and digital advertising in particular.

I actually think that has had an impact as well on the broader global perceptions of the economy, because media, tech, finance, these are very influential industries, in terms of how people generally see the economy, the media, obviously. I'm not surprised that some of the negativity that people in those industries feel about their own businesses has seeped more generally into the broader views of the economy.

Brigid Bergen: James, you wrote in your piece, "If the policy response had been less aggressive, the US economy would be in worse shape now. We have a bit of a comparison to what it could have been like if we look at Europe." I'd love for you to talk about that a little bit further, but I want to also read a text that we got from a listener that connects to this idea which the listener writes, "Inflation rose worldwide after the pandemic, and USA fared better than most nations. Did Biden cause inflation in France?" Can you talk a little bit about what the-- [crosstalk] Yes, go ahead.

James Surowiecki: This is a really important point, and it was basically the real thesis of the article I wrote for my most recent article for The Atlantic. I think that one of the reasons why this debate, or whatever it is we're having, this conversation about why people feel so gloomy matters is not just a kind of, you want people to see the economy as it is, you do, but the bigger reason why it matters is that my main concern is that you don't want the gloom people feel or the negativity people feel by the Biden administration to translate into people saying, the next time we have a big downturn a recession or whatever, we should really be much more cautious in how we respond to it.

We don't want the government to step in and try to help people out or whatever. I actually think if you contrast the US's response to the COVID recession, to what happened in 2008, and 2009, and our response to the global financial crisis, we were far more aggressive this time around. The result is that we rebounded so much faster, and people are so much better off three years, or whatever it is two and a half years after the COVID recession, than they were two and a half years, or actually, even four or five years after the global financial crisis recession.

It's really important to take away from this that we are not helpless in the face of recessions. The federal government can step up. It can make things a lot better for ordinary Americans and that's what happened. We had enhanced unemployment benefits, we had the child care tax credit, we had the stimulus payments. Those things not only helped Americans, quite literally, just in terms of giving them money they wouldn't otherwise have had, but it also helped businesses because it meant there were customers and it helped business get back on its feet a lot faster. That I think is really important.

Yes, the contrast to Europe is really worth noting. Europe generally responded less aggressively than we did. Europe has inflation that pretty much is the same as ours, it might even be a little bit higher right now. They also have much higher unemployment, and their economies are growing much more slowly. In some cases, some of them have gone back into recession. That's the real counterfactual, I think.

The problem is that understandably, the average American who goes to the grocery store isn't saying to themselves, "If I were in France, it would just be just as expensive."

[laughter]

James Surowiecki: It's not something we're going to do, and I don't think we should. I understand why we don't, but I do think that is the thing to keep in mind.

Brigid Bergen: James, before I let you go, we started this conversation, and I played a little clip from the House yesterday, passing that stopgap measure to avoid a government shutdown. According to CNN, the bill would extend funding until January 19th for priorities including military construction, Veterans Affairs, transportation, and housing in the Energy Department. That is a crisis averted, at least for now.

James Surowiecki: For now, yes.

Brigid Bergen: Does it feel like there's always this potential shutdown with the fact that this potential for shutdown continues to loom? How does it impact the feelings of the economy or even voters' impressions of the stability of our government?

James Surowiecki: I do think it has an impact. I do think this sense of lurching from crisis, or almost crisis to the next almost crisis, [chuckles] has an impact, just generally on the way we feel about the economy, the way we feel about the country, and the like. We went through the whole debt ceiling crisis earlier this year, that was averted at the last minute. This is a little bit different. This is not about the debt ceiling, this is a continuing resolution to fund the government but it's basically coming from the same place. Yes, I think this whole general sense of unease and anxiety that people feel, I think it permeates our view of the economy.

I would say one of the thing which is, I actually think that's part of why the rising inflation was so unsettling to people, is just that it felt new, we hadn't dealt with it in a long time and I think also, there's something about inflation that makes people feel like things are a little bit out of control. It just, again, contributes to this general sense of, something's off. I think that explains some of what people are really expressing when they say, I'm much worse off than I was two years ago, even though you probably aren't much worse off than you were two years ago.

Brigid Bergen: [chuckles] James, thank you so much for joining me. We're going to leave it there for now. My guess has been James Surowiecki contributing writer to The Atlantic and the author of The Wisdom of Crowds. We really appreciate you joining us this morning.

James Surowiecki: Thanks for having me on. I appreciate it. Thanks.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.