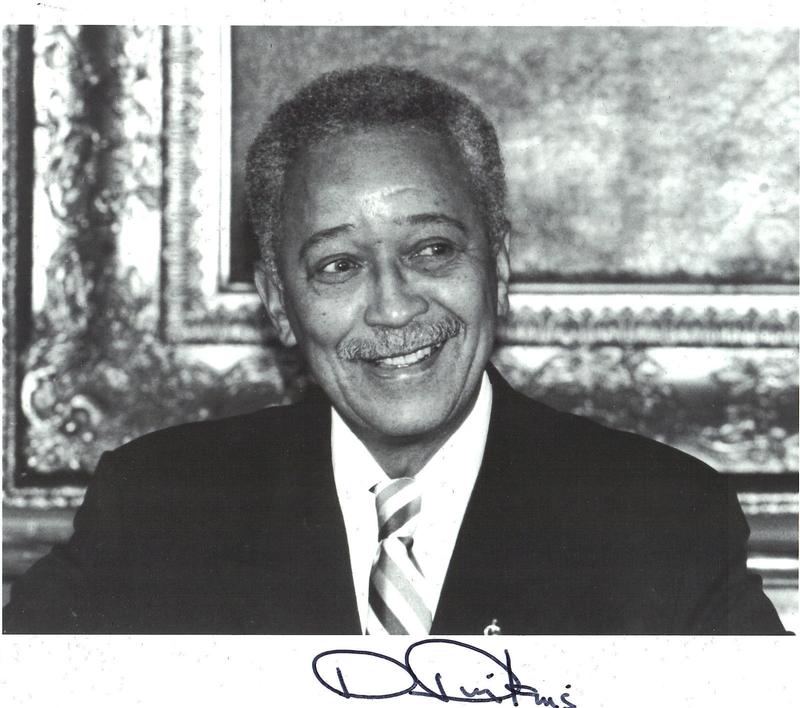

David Dinkins' Life & Legacy

( WNYC Archive Collections )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning everyone. Let's remember Mayor David Dinkins, who has died at the age of 93. Let's remember him as a person and let's take a trip back in history to the years of his rise and the four years he was mayor elected in 1989 before being defeated for reelection by Rudy Giuliani in '93. Let's talk about how all that back then informs all of what's happening today. We'll open up the phones for your David Dinkins thoughts in a minute, and we've got some great guests, but first here's a clip of David Dinkins on this show in 2009. The occasion was the 20th anniversary of his election as mayor and it happened to be the year that Barack Obama took office as president of the United States. I asked David Dinkins this. Do you think that you paved the way for Barack Obama in any respect?

David Dinkins: We have this expression Charles Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and I and others we say, "Everybody stands on somebody's shoulders." By that, we mean Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Rosa Parks and for me personally, Percy Ellis Sutton ran with such class and distinction in '77. They didn't laugh at me when I dare tried in '89. In that sense, yes, Obama stands on the shoulders of all of us. Had Jesse Jackson not run so well in 1988 and I was the co-chair of his campaign in New York state, and we registered a lot of people of color, and I got maybe 95% of that vote, I would not have succeeded.

Brian: David Dinkins with us here in 2009. With us now, former New York governor and former state Senate Minority Leader as a state Senator from Harlem, David Paterson. David Paterson was growing up and starting his political career when his father Basil Paterson was one of the four main Harlem powerbrokers known as The Gang of Four along with Dinkins, Charlie Rangel, and Percy Sutton, as Dinkins mentioned in that clip. Dinkins also gets mentioned in Paterson's new book, which is a memoir called Black, Blind, & In Charge. Hi, governor. Great to have you on again. Welcome back to WNYC.

David Paterson: Brian, it's been a long time. It's great to talk to you.

Brian: Want to start by reacting to that clip in which Dinkins mentioned your father and talks about that lending edge of shoulders to stand on?

David: I think that the former mayor, the late mayor, I hate to say at this point, laid that out very well that there were strides that were taken by some and others were able to go further. Sometimes those who took strides knew that they were limited in how far they could go, but they paved the way for others to go further, absolutely. There are so many people who would have been president, would have been governor, would have been mayor, but our country had not gotten over the 244 years of slavery, another 100 years of segregation, and that's why it took so long.

Brian: For listeners who don't know this history, who is your father, Basil Paterson? I know, but a lot of listeners don't know and what was the context of this Gang of Four, as they were known as neighborhood political leaders, your father and Dinkins and Congressman Rangel and former Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton?

David: My father grew up in Harlem. He was born in Harlem. He went to St. John's Law School and became a lawyer. Unfortunately, when he was 16 years old, he was getting off of a subway and he had his baseball glove. He was coming from playing stickball and a police officer asked him where he got the glove and he told him it was his glove. The officer pistol-whipped him and the NAACP came to my father's house and said that there were 20 witnesses, three of them white, what the officer had done to him and they wanted to file a suit against the New York City and the police department.

My father's father, my grandfather said to them, "You can do that, but you can't protect my son who's out on the streets if we have that lawsuit." He forbid them to take this lawsuit. I think my father felt badly that that couldn't happen. That was when he said-- he was 16 that was when he decided he wanted to be in public service. He was with Percy Sutton and a particular club and Dinkins and Rangel were in a different clubs. They were actually adversaries when they first knew each other. When my father ran for the state Senate in 1965, I was 11 years old and we would campaign and we were taking David Dinkins signs down, which seems quite interesting in terms of the years coming.

The reason I think that they were linked together is because they were all very talented. They all had great ability, but they also had an ability to compromise with each other because in other neighborhoods, there were some people, I would say their talent was comparable, but they just couldn't stop fighting. All of these men had diplomacy in their vocabulary and that's why they are as heralded as they are now.

Brian: Dinkins was the least flamboyant of the four. I think it's accurate to say. How did he become the one to rise to mayor?

David: Yes. Jack Newfield once said, "If the gang of four were the Beatles, Dinkins was Ringo Starr." Yes. My father was the one who was scheduled to run for mayor in 1985. He developed a heart condition that made him feel that he could not interact as much as he could before. Dinkins runs and wins for borough president in 1985. Rangel was looking to become ways and means chair. He wasn't going to leave Congress. Sutton had left government after he lost the 1977 mayoral race to run inner-city broadcasting, the FM radio stations, and had a cadre of radio stations around the country. It really was Dinkins who was next in line.

I don't think Mayor Dinkins himself wanted to run for mayor. His big ambition was to be borough president, just to give you the idea of the diminished expectations that were in the black community at that time, but what changed it was the court case that held that the Board of Estimate had to be dissolved because it violated one man, one vote or one person, one vote.

Brian: For people who don't know, it used to be something called the Board of Estimate, not the City Council that held most of the political power in New York. Go ahead.

David: Most of the political power. Dinkins as borough president was going to lose a lot of power and that's when the idea of running for mayor came to him in late 1988 and he announces and wins in '89.

Brian: Listeners, we do want your David Dinkins memories, we want your David Dinkins tributes, we want your David Dinkins questions for former Governor David Paterson. One second. Let me just give out the phone number for our listeners so they can join. 646-435-7280. 646-435-7280, or tweet @BrianLehrer. Governor, go ahead.

David: I've done a lot of interviews in the last few days and they always preempted what I said and they had me quoted as saying what everyone else said that he was a wonderful gentleman, people liked him, he was appreciated on both sides of the house, he loved kids and he was great to work with. What I wanted to point out is that I think in terms of what's going on today, that history is very anachronistic when it comes to Mayor Dinkins.

For instance, you hear people saying now the subways dangerous, there' homelessness all over the city, crime has spiked. This was the worst thing since the '80s. Then when they're unhappy with Mayor de Blasio, they say, "This is the worst thing that's happened since Dinkins." They connect Dinkins with what was going on in the '80s when, in fact, he never served one second of the '80s as mayor of the city of New York. He was elected in 1990. Now, former Police Commissioner Ray Kelly said yesterday that between 1984 and 1990, this was before Dinkins comes in, that crime spiked 64% in the city. That 64% took the death toll from homicides over 2,000 by 1986. When Dinkins became mayor, we already were losing 2,000 new Yorkers every year.

It stayed over 2,000 for two years and then Dinkins cut the crime rate by 25% with his Safe City Streets Act that was passed in Albany. This notion that all these terrible things were going on during Dinkins actually went on during Mayor Koch. I'm not here to disparage Mayor Koch. The real cause of the problem all around the country was the crack epidemic that started in 1985, but this whole idea that Dinkins supervise the lawlessness that he caused the budget to become imbalanced. When in fact, when he left office in 1993, New York City had a $500 million surplus, which mayors public officials are not known for leaving surpluses because they could spend that money on programs before they left.

The 6,000 police officers that Dinkins got from federal money for the Safe City Safe Streets Act did not join the force until the administration of Mayor Giuliani. I just wanted to make the record straight. I'm not saying David Dinkins was greatest mayor that the city ever had. I'm saying he was a very good mayor.

Brian: I talked about this on yesterday show, too how crime was going up and up and up on Ed Koch's watch for those 12 years, certainly the murder rate as you just cited, and yet people didn't seem to hold him personally responsible for it in the way that they did mayor David Dinkins in his first year. You want to just say it, do you think that was racist?

David: I think it was racialized. I don't think that some of the people who've said it are actually themselves racist, but to equate the crime, which they saw as being committed by Black and brown people with what they saw as the ineptness of Dinkins when, in fact, they put it on his report card and he wasn't even in school was really outrageous.

It's one of the reasons I'm so happy you gave me the chance to say this because I said it to everyone else and they take the clips and they had me saying he was like an uncle to me and yes, he was like an uncle to me but what they're going to do is be nice to Dinkins for a few days now that he's passed away and within six months, we'll be back to saying, "Oh, back when Dinkins was mayor, all these things went wrong." Dinkins was a healer and an administrator that changed things. He's the one that implemented the Civilian Complaint Review Board in 1992,

Brian: Not only that he was the first one who hired Ray Kelly and he was the first one who hired William Bratton to fight crime in New York City and he raised taxes to fund more police. You mentioned the Safe Streets, Safe City program that was largely simply to increase the number of police officers on the force to start to really fight back that crime. Imagine a Democratic politician today proposing to raise taxes to fund the police for more cops.

David: I'll tell you something right now. If I was in government right now with the problems that have occurred with police departments around the country, I would devote more money. I would refund the police department and change the whole concept of policing rather than defunding a system that to many people isn't working and then let it look even worse than it did before.

Mayor Dinkins may have taught us a lesson particularly Democrats who are quick to adopt these like a little slogans that really don't make any sense. If you're going to clean up the police department, you're going to need more resources and that's exactly what the mayor did. That was a very good point, Brian.

Brian: We're remembering David Dinkins, the late mayor of New York from 1989, elected in '89 and served through '93 has one term with former governor of New York, David Patterson. Kenny in the Bronx. You're on WNYC. Kenny, thank you for calling in.

Kenny: Oh, Brian, we love you in the Bronx. My governor, we love you too. My first experience when I was 19 years old, [unintelligible 00:14:01] Latinx gay young man seen somebody run for familiar. In the part of the time, when we were apathetic, we got involved and it was an experience and we saw a lot of old hands at politics and they didn't let us in and Bill Lynch was the campaign manager God bless his soul and he said, "No, that kid needs to do this and that." He put us to work and all of us young Dems from the Bronx and Harlem got together and nice long friendships I've made from that. I would never be involved in public service without him. I really appreciated the dynamic Harlem for and the group that made us dream in the Bronx.

Brian: Kenny, nicely put, thank you so much. Please call us again. Hassoni in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC. Hello, Hassoni.

Hassoni: Hi, actually Brian I'm calling you, I live in Brooklyn, but I'm in Martha's Vineyard right now so take you wherever I go. My memories of a mayor Dinkins as more so about his love affair with his wife. His wife, the beautiful enormously classy Joyce Dinkins, and how he would always be concerned of where Joyce was and his love and concern for her was just a true model for what life should be with the person that you're married to and their legacy of marriage of what almost 70 years is something that I truly admire.

I do believe that he died of heartache, I think it was very difficult for him to be without her. I know that people I know who were very, very close to him and talk to him every day, talk about just how much he missed her and so I'm sure that he is finally reunited with her and it's probably dancing and looking forward to spending eternity with his wife as he always had envisioned since 1953. [crosstalk]

Brian: That's so beautiful, Hassoni. Thank you very much. David Patterson, Joyce Dinkins just died a few months ago, and then the mayor.

David: On the mayor's inauguration day, they were riding to the inauguration and there was a construction site and they were looking at the construction workers and Dinkins said to his wife, "This guy, he looks like this old boyfriend of yours that you had years ago." He said it could be him and she said, "Yes, it does look like him." He said, "If you'd married him, you'd be married to a construction worker." Mrs. Daikin said to the mayor, "If I married him, he would have been mayor."

Brian: Who's the real power broker in the family and she just died last month.

David: She died on October 12th, he died six weeks before him.

Brian: Rosie in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC. I have a feeling I know which Rosie in Brooklyn this is. Hi, Rosie.

Rosie: Hi, Brian, how are you? Happy holidays. Hi David, how are you as well, I miss seeing you?

David: How are you?

Rosie: Good. I was going to say that, yes, Rosie Price, this is me. Yes, it is and [crosstalk] and I love you. I wanted to say that a young budding activist in the ACE movement, Mayor David Dinkins was the first elected officials who ever reach out to me personally and ask me to help New York shine and said that I had a very promising career as an activist and what I consider being an elected official. I said, "Oh, no, I'll just leave that up to you," but he introduced me around towns. I got to know all the political players and he taught me a lot. He also invited me to US Open once he found out that I was not only a boxing fan but also a tennis fan.

It was just amazing to go to the US Open with Mayor David Dinkins, but it was even more equally amazing to be acknowledged for my activism. To lend that hand, to extend that hand, how many elected officials do that? The only other elected official that has ever personally reached out to me was Congresswoman maybe of Alaska. Of course, it was then Senator Barack Obama, but David Dinkins was the first.

He was the first person to do that and I wasn't the only person who previous up a young man just stated that he reached out to him too. He just saw people who were on the grounds trying to make a difference. He was like, "Come on inside, get on the inside, and let's make the city a better place." I miss him dearly. I miss him dearly.

Brian: Thank you for that beautiful tribute, Rosie, thank you so much for calling in. David, she mentions the tennis stadium in Queens. I don't know that there's ever been a better stadium deal financially for the city and state of New York. Do you ever thought of that?

David: Yes. The US Open was ready to move out of New York and they were able to put it together. By the way, I think it was in very poor taste that when mayor Giuliani succeeded, mayor Dinkins said he never went to the Westside tennis club. He never went to the US Open. He was always pronouncing that there was chicanery in the way their contract was set and I see that that kind of reaction, we haven't lost that here in America, but when we do, we'll be doing a lot better.

Brian: I wonder if the Yankees are embarrassed, that Giuliani wears his New York Yankees world series ring every day as he's doing these wacky news conferences but we'll have to ask the New York Yankees also joining us for a few minutes. Ester Fuchs, long-time, Columbia and Barnard public affairs professor who helped bring Mayor Dinkins to Columbia to teach after his mayoralty. She also worked for Mayor Bloomberg in his first term. Hi, Esther. Welcome back to WNYC.

Esther: Hi, Brian. Oh, it's great to talk to you and to Governor Paterson, who he knows I'm a long-term fan of Governor Paterson and his perspective is so important.

David: Esther, happy Thanksgiving, how are you?

Esther: Thank you, sad like you, but we're thinking about Mayor Dinkins, we all get to smile.

Brian: What do you think is important to remember about David Dinkins?

Esther: I think over the last couple of days, we've been doing a really good job in getting people to understand what his true policy legacy is. I won't go through the litany of things. I think Governor Paterson really covered them. I would just say not to forget the Beacon Schools, which were part of the Safe Streets, Safe Cities program, because that was the community policing and helping young people essentially after school and on the weekends.

One of the few things that has managed to stay in place through the Giuliani years and of course, Mayor Bloomberg expanded it it's an extraordinary program Beacons and it has become a national model, but he did so much at the community level that people don't really recognize. I agree with David, which is there's this, oh, focus on his dignity and his grace and his courtliness, which all of which is true, but it was for a purpose and I think people need to put that into context, particularly in modern politics now, Mayor Dinkins came to Columbia to teach kids, to teach young people and to listen to them in the way he did throughout his entire career.

He continued to engage in civic life. When he went to charity events, it was not to put on a tuxedo. It was to help these amazing organizations raise money for the causes that he believes were so important whether it was posse for college prep or agency, association to benefit children and his wonderful friends, Gretchen Buchenholz, he considered all of her kids and daycare and all of her programs, his kids, the junior tennis league, children's health fund, all of that was for purpose. He lent his name and he showed up, who shows up? No one shows up.

Then what he did at Columbia for students was what he did when he walked down the street and when people stopped him and he would not just allow them to take a selfie with him, but he would stand there and listen and encourage and engage. I never saw anything like it. I just had the good fortune of having this office that opened up to his office.

I could see what was going on and he always invited me in to meet the so-called important people who would come in to see him and ask him for something. He did not turn anybody away. He would treat one of the SIPA students the same way he would treat Reverend Al Sharpton, who came to see him over the years, many, many times, and who he treated also respectfully, which I always found to be quite amazing and extraordinary to be perfectly honest.

Brian: Did he? Because I read it as I was just trying to remind myself of some things about the Dinkins years, I was reading some old New York Times clippings and one of them referred to Al Sharpton, calling Dinkins a political whore.

Esther: That is exactly right. I'll tell this very quick story because it just shows you who Mayor Dinkins was. Fairly recently, Reverend Sharpton came to see him and my door was open and I could hear part of the conversation and people come when they need something and he was respectful. He listened, he provided the advice and he was genuinely warm and Reverend Sharpton left.

I have to tell you, I walked into the office because he expected me to do that. I looked at him and I said, "How could you do that? How are you able to do that? Why did you do that?" Governor Paterson will recognize this story because I know it's happened to him so many times too. He would smile, his smile. It was a deep, deep smile of knowing.

He said, "He's changed and he's doing good things now and we need to be supportive of anybody who's really trying to engage the civic conversation in a way that helps people who are underrepresented," as he used to like to say, "Helps the least among us." He recognized that and he was going to hold this any personal animus. I'll tell you, I don't know how he could do that, but he did and he meant it and it was real. The one thing I would just say is the authenticity of this man was so deep and so great.

He knew what he had to do and he knew that he had to do it his way. When I say civil discourse, I say this now with great importance. He was about figuring out what people had in common. We all know that for him to win that mayoralty the first time, he needed to get 30% of the white vote and he did and it was close. It was hard to do and New York was the last of all the 10 largest cities in this country to elect a Black mayor. As David pointed out, it was a very, very difficult time that he came into office that he inherited, but he did that.

This gorgeous mosaic was not just a metaphor. It was a recognition of people's differences, but that there's ways of fitting the pieces of the mosaic together and figuring out what we have in common. It's so much easier to run a campaign, dividing people. That's what we saw in presidential politics with President Trump.

That's what he's done, sow the seeds of poison all over the country and Mayor Dinkins had to run against Rudy Giuliani, who did that in New York, sowing the seeds of poison in our communities all around the city, but Mayor Dinkins, persisted, he continued, he continued to live a life that demonstrated that you can be respectful to people. You can get things done because it's important to recognize how much he actually got done and that you can live a life of grace and dignity and caring and still be tough and successful. I think he did that. He did that in the most beautiful way.

Brian: Not only is that hard to top. That's a good reason to end the segment. We are also out of time except Ester Fuchs.

Esther: Thank you Brian. Thank you, David.

Brian: I hear the emotion in your voice and for all the times that you've been on the show doing hardcore political analysis. I don't think I've heard you like this before. Ester Fuchs from Columbia University. David Paterson, you get the last word at 30 seconds.

David: Here's to Mayor David Dinkins and his wife, Joyce, who I would like to feel are up in heaven preparing for Thanksgiving.

Brian: Former Governor David Paterson's new book, by the way, his memoir, which refers to David Dinkins among so many other people and things is called Black, Blind, & In Charge. Thank you so much, governor.

David: Thank you, Brian. Great to talk to you.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.