Cancelling the Arctic Leases

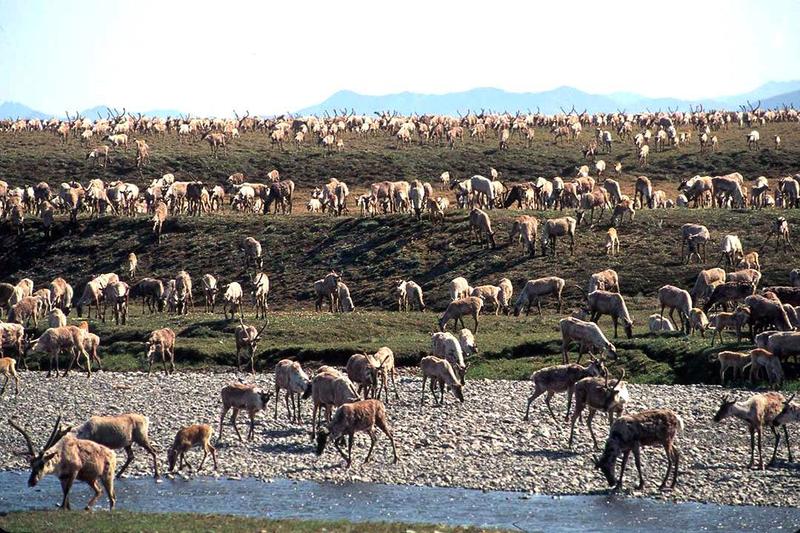

( U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service via AP, File / AP Photo )

[music]

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now, our Climate Story of the Week, which we're doing every Tuesday all this year on the show. A piece of big climate news in the last week is President Biden's decision to cancel seven oil drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge leases that were sold during the Trump administration. An article published by Vox this week begins with a line that the Biden administration can't make a move in the Arctic without a political mess.

This cancellation infuriates the oil companies as you might imagine. A decision this year to approve some drilling there raised the ire of environmentalists, so let's take a closer look. We'll touch on another piece of climate news too. A UN report that says the 2015 Paris Climate Accords are not producing enough change to meet its goals even though almost every country in the world signed on. With us now, Rebecca Leber, who wrote that Arctic story and covered the UN's Paris Accords assessment and covers climate change generally for Vox. Rebecca, thanks for coming on. Welcome to WNYC.

Rebecca Leber: Yes, thanks for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start in the Arctic and let's start with a background question. When we talk about the Arctic, where are we actually talking about geographically?

Rebecca Leber: It's a great question. Well, we're talking for these purposes, the Alaskan Arctic, so northern Alaska, the North Slope, which contains two really important pieces of land. One is called the National Petroleum Reserve and the other is called the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Brian Lehrer: How are they different?

Rebecca Leber: Well, unlike what the names imply, these are both really important regions for wildlife conservation as well as to Indigenous communities. The National Petroleum Reserve has a slightly different history, though, where it is open to oil development. That doesn't mean it's all open for oil. This is where the controversy has been over how much land would be protected. Then when we talk about the Arctic refuge, we are talking about really pristine lands that have never been open to fossil fuel development despite the oil industry really trying for decades to open that land.

Brian Lehrer: Before we even get into the policies, I guess the two area names might evoke very different reactions in our listeners. National Wildlife Refuge might sound like something to be protected from corporate destruction, climate change, or no. Strategic petroleum reserve might sound like something the country needs in case of emergencies like when the supply chain spiked the price of gasoline in the pandemic or if there's a war. I don't know if you can answer this, but is it right to think of them differently in those ways?

Rebecca Leber: It's certainly different in how they've been regulated over the decades. If you look at a map, these are situated pretty close to each other. Nature doesn't necessarily recognize those same borders and wildlife particularly overlap for a lot of these lands. Because of how these lands were governed going back to the Eisenhower administration, we have one area that's been closed off to drilling and another that has been a lot more open to it.

Another important piece of infrastructure here is that there's a pipeline that carries oil from the petroleum reserve to a port in southern Alaska. That pipeline's really important here because as your listeners are probably aware, permitting fights have long plagued a lot of projects for developing oil pipelines. Here, there's a pipeline that already exists to carry that oil, which makes it also a target for the industry, why they would want to keep drilling there.

Brian Lehrer: Okay, what exactly did Biden cancel in the wildlife refuge last week?

Rebecca Leber: Well, he canceled seven oil leases from an Alaska-owned oil company. This is an important detail because the Trump administration, when it opened up the Arctic refuge to oil drilling or oil permitting for the first time in its history, very few oil companies came to bid on these leases. There were only a handful of companies and a few of them actually voluntarily gave up their leases at the time. What Biden had before him to cancel, there was pretty slim pickings. There were very few leases left where there was any intent to hold on to it. In terms of the impacts of canceling those leases, it's fairly minor in the scheme of things.

Brian Lehrer: Even if we believe this is good for the world and that not many oil companies were even interested in there anymore, as I think you just said, does this break faith in some way because the President broke leases that were agreed to and signed?

Rebecca Leber: Well, yes, this is an interesting tension because, of course, Trump had approved these leases. This was very controversial in itself in the environmental community. What we see here is Biden trying to walk a really fine line here between the oil industry and environmentalists. This takes us back months ago to when the administration approved a different oil project in the petroleum reserve for ConocoPhillips that would expand oil drilling in Alaska. That really angered environmentalists. Here, we see an attempt to offer essentially an olive branch that Biden is expanding regulations and protections in the region. There's really no making anyone happy here. Biden is trying to walk a line.

Brian Lehrer: Well, how do these two things even fit together from Biden's perspective, canceling seven existing leases in the Arctic and approving a new one that you describe as vast?

Rebecca Leber: The seven leases that were canceled, that is in the Arctic Wildlife National Refuge, which as we were talking about is this area that has never been opened for drilling. The Willow project, which is the vast oil project that Biden did approve back in March, that is located in the National Petroleum Reserve.

The administration argues here that their hands were really tied legally, that they had to approve ConocoPhillips permit for building there, that they would've lost in court cases if they had even tried to fight it. This is still a fight going on in the courts where environmentalists are still suing over the project, but the administration basically says it didn't have the legal ground to fight on the Willow project. While it feels confident, it does have a case to cancel these leases in ANWR.

Brian Lehrer: Can you go into the bet that you write that ConocoPhillips is placing? This is so interesting and probably something that a lot of our listeners have not heard about before to pay off this bet on that drilling in the strategic petroleum preserve in the Arctic. To pay off, it seems from your article that gasoline prices would have to stay high for decades and the transition to electric vehicles would have to stall out compared to what's now planned. Climate action would have to fail in other ways too, yes?

Rebecca Leber: Yes, this is a really fascinating foy that ConocoPhillips is using here because it's also somewhat unique in the oil industry, at least in the Arctic, that taking a step back for oil prospects to pay off that they would obviously need to make more money than it costs. It's just very expensive to drill in the Arctic. There are lots of challenges here like frozen roads, ice, just weather in general. This has nothing to do with environmental regulations, why it's especially expensive to drill there. There's a lot of risks. To benefit from Arctic drilling, oil prices have to be high.

For the last decade or so, oil prices were not high enough to really justify even looking for Arctic oil. That's when we saw companies like Shell abandon their prospects in the Arctic entirely partly because oil prices wouldn't justify it and partly because there was some environmental pressure that they do so. ConocoPhillips here is taking a different approach saying, "We bet that oil prices remain high enough that this is still profitable, that the Willow project specifically will carry oil for the next 30 to 40 years and make a lot of money because prices will remain pretty high."

Now, that's in contrast with lots of projections around what we need to do for climate change. The International Energy Agency alone says we need no new fossil fuel infrastructure in coming years if we are going to meet our climate goals. Just today, the same agency said they expect demand for oil to start to peak in just the next few years, or they expect for fossil fuels overall that we would start to see this decline, which would effectively mean prices come down. There's this tension where oil companies are essentially betting against climate action by investing in the Arctic.

Brian Lehrer: Right, and you're right that ConocoPhillips, however, is almost the only oil company betting right now that drilling in the Arctic is a good investment under these changing political and policy circumstances moving to EVs. What do most oil companies think and why are there divergent predictions?

Rebecca Leber: Yes, this is really interesting because we see a lot of oil companies holding back from the Arctic specifically. Like I was saying before, just a few reasons here. One is the oil prices. Another is there's been pressure, especially on banks that help finance these projects, to stop funding Arctic drilling. We do see some major companies like BP, like Shell that have walked back their investments there, but that doesn't mean they're not investing in oil elsewhere.

Pretty much, every oil company across the board is playing this hypocritical game around climate change where they say, publicly, they're committed to net zero by 2050, but they're also saying, "We are investing in more oil projects. We are going to keep drilling and keep finding new oil," even though that's something the world can't afford, and that a lot of companies might be holding back on the Arctic specifically because of some risks unique to the region, but that doesn't mean they're holding back elsewhere.

Brian Lehrer: Right, it's a more expensive place to drill, so maybe not worth the gamble as you were describing before. Why do you think ConocoPhillips thinks that's a good bet? Even after the increase in wildfires and record heatwaves and other climate-related extreme weather events that the general, non-activist public is feeling personally more every year, why do they think climate action politics will fail?

Rebecca Leber: Well, I think essentially like most things, it comes down to profit that ConocoPhillips has had these leases sitting around since the '90s and hasn't developed the Willow project in Alaska. If it does develop as they expect, it would produce a lot of oil in the next 30 years and potentially make them money if their bet pans out. The Arctic drilling, despite the cost, they're planning on making profit here.

This is where we see that tension where companies aren't really holding true to these values around climate change. They're just looking at the bottom line of what they can squeeze out for their oil prospects. Oil companies have-- they try to exploit their cheapest resources and cheapest oil reserves first, but that's not always available to them. For ConocoPhillips, this is a prospect for them to make a lot of money.

Brian Lehrer: Do native peoples and native lands in Alaska come into this conversation or not so much in these particular areas?

Rebecca Leber: It definitely does. This is where it gets complicated fast because you sometimes see a split where some Indigenous communities might be favorable to oil development if it benefits economically that community. Then we also see, on the other hand, communities that have protested, have penned letters to the Interior Department asking for them to revoke these leases, saying that not only it affects their way of life, it affects the wildlife in the region and permanently would reshape the ecosystem while not sending any kind of benefits to the community itself that they would bear the cost of the pollution but not the profits.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we are in our Climate Story of the Week, which we do every Tuesday here on The Brian Lehrer Show all this year. Your questions, comments, stories, all welcome on the two things that we're discussing today with Rebecca Leber, who covers climate change for Vox. This week, it's oil drilling in the Arctic and the UN report on the Paris Accords falling short also. Rebecca, get into this after a break.

Now that we've been talking about these particular Biden policies with respect to the Arctic in particular, we're going to talk about climate as a 2024 election issue. We're going to play a couple of clips from the Republican debate the other week to give you an indication of what Biden is probably going to face no matter who the Republican nominee is and talk about that with Rebecca Leber from Vox and maybe with you. On any of those things, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, call or text or tweet @BrianLehrer, and we continue after this.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. We are in our Climate Story of the Week with Rebecca Leber, who covers climate change for Vox. Onto these politics, Rebecca. The Republican Party seems like ConocoPhillips to also be betting on the failure of climate action and that climate action will be seen as unpopular in next year's election cycle. Let me give you two examples from last month's Republican presidential debate. First, here's a very short clip of Vivek Ramaswamy claiming a fossil fuel is imperative for average Americans' prosperity.

Vivek Ramaswamy: God is real. There are two genders. Fossil fuels are a requirement for human prosperity. Reversed racism is racism.

Brian Lehrer: I know there are a lot of other bullet points in there, but one of them was fossil fuels are necessary for human prosperity. Here's Nikki Haley, slightly longer clip about 45 seconds, who only can cite climate policy she's against when asked if she accepts that climate change is real.

Nikki Haley: Is climate change real? Yes, it is. If you want to go and really change the environment, then we need to start telling China and India that they have to lower their emissions.

[applause]

Nikki Haley: That's where our problem is. These green subsidies that Biden has put in, all he's done is help China because he doesn't understand all these electric vehicles that he's done. Half of the batteries for electric vehicles are made in China. That's not helping the environment. You're putting money in China's pocket and Biden did that. First of all, I think we need to acknowledge the truth, which is these subsidies are not working. We also need to take on the international world and say, "Okay, India and China, you've got to stop polluting," and that's when we'll start to deal with climate--

Brian Lehrer: Start to deal with the planet. Nikki Haley and Vivek Ramaswamy from last month's debate on Fox. Rebecca, what do you make of those answers and what it says Biden will be up against whoever the Republican nominee is next year? Assuming it's Trump, I don't think he's very different from those positions with respect to how climate policies get debated.

Rebecca Leber: I think we might all realize that climate denial isn't new for the Republican Party. This goes back a while. This was a heavy feature of Trump's administration and presidential election last time around. What I do think is new and coming through in those clips you shared is that climate change has increasingly become integrated in culture war rhetoric, that this is about a lifestyle choice, and this us-versus-them battle in a way that maybe we didn't see about a decade ago where it would have been Republicans disputing the science itself and saying that there's no evidence of human-caused climate change, even though there is no evidence supporting that.

Now, what we hear is that candidates are skipping that entirely. They will lose at any kind of debate on the scientific merits. They're keeping this heavily focused on cultural issues. I think one example of that is how focused Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has been around gas stoves and incorrectly characterizing bans on gas stoves as this fight over lifestyle choices and equating this with the climate fight. Even though, of course, climate change action, we're talking about a much broader scope of economic issues and regulations and so on. The focus on people's lifestyles, I think, is a newer trend.

Brian Lehrer: I guess it's getting harder to deny that climate change is real because the statistics are out there for how the average temperature has been increasing decade by decade, year by year. We've talked on the show many times about how the nine hottest years since they started keeping records are the last nine years. July was the hottest month on record globally ever. The warming is undeniable. Do the Republicans come out in your reporting so far with alternative methods of mitigating it if they don't want things like offshore windmills or gas stoves converting to electric?

Rebecca Leber: Yes. The short answer is no, Republicans don't have solutions for climate change, or at least nothing that is even remotely serious to the challenges ahead. I've interviewed Bob Inglis, who is a former congressman, who has since dedicated his career to fighting for climate action from a conservative perspective. Even he says that the Republican Party doesn't have the solutions that are appropriate for the crisis that we're facing. Those kinds of solutions need to tackle things like unabated fossil fuel emissions.

Republicans really neatly try to sidestep that issue entirely. The one proposal that we're seeing more Republicans coalesce around is this idea that we can save ourselves by planting trees. This is an interesting proposal because, of course, everyone loves trees. Trees can do a lot for the environment and the climate. By only focusing on trees, Republicans are missing the forest here that there are a lot more solutions needed in order to bring down emissions so that this idea is not even remotely appropriate for the kinds of challenges we face.

Brian Lehrer: In our Climate Story of the Week, which we do every Tuesday with Rebecca Leber today who covers climate change for Vox, and we started this conversation for those of you who have joined late by talking about Biden's somewhat contradictory policies for drilling in the Arctic in Alaska. We're getting a call from Lawrence in Anchorage. You're on WNYC. Hi, Lawrence.

Lawrence: Hi. Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: Can hear you just fine. Hi.

Lawrence: Hi. Yes, I live here in Anchorage. I've lived here for a number of years since the '80s basically on and off. I understand a little bit about what the relationship is between the oil industry and our local economy here. I don't know if you're aware, but BP pulled out entirely from the area a few years ago. There's an empty office building that they were here since day one of the pipeline basically and they're gone. A lot of high-end jobs, oil industry jobs are gone.

We lost thousands of jobs over the last few years here and so that's affected the economy. Also, I don't know if people are aware of this, but a lot of the people that work up on the slope where this drilling is occurring, they are not even from the state really. A lot of them do shifts like two or three-week shifts on and off. They leave the state and their money goes. We don't have an income tax or a sales tax here, so we're not getting a lot of benefit from that.

The only thing is, every year, we get a dividend as they call it, which fluctuates according to what the fund is, but that's going to dry up at some point soon. They're drawing money from that fund too because the economy here is so bad. We have a huge deficit and we have a very conservative politics here. We have a very conservative governor, very conservative mayor in this town. I don't know what to say about it, but we're not really benefiting as far as I'm concerned from the oil industry the way it used to be when the pipeline first opened.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, and yet the sentiment of the majority of Alaska voters, you would say, is, "Drill, baby, drill," because that's where they see potential benefits for them coming?

Lawrence: Well, I don't know. I think it's kind of mixed here. You have a lot of people that are looking at the end days here because I think people realize that, at some point, the end is going to come to the oil. There's not going to be that stream of income. Also, we're also experiencing climate change here. I called a few months ago about that. We've had a lot of extremes in climate here in Alaska over the last number of years. I think people are realizing that. Villages are sinking. The tundra is melting. There's glaciers melting. Juneau had a big glacial dam that broke and flooded areas. We have a lot of stuff going on here due to climate change. I don't know. I think it's a mixed bag as far as drilling.

Brian Lehrer: Lawrence, thanks for the view from Anchorage. We really appreciate it. Aaron, with the view from East Meadow, Long Island, you're on WNYC. Hi, Aaron.

Aaron: Hi, Brian. Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Aaron: Okay, I wanted to talk about quickly the inextricable link between politics and climate action. Particularly in the context of the Democratic Party having a proper primary this year, it seems that the Democratic National Committee has boxed out all primary opponents to President Biden. They have effectively chosen a winner before there has even been a primary. There are qualified candidates to primary Joe Biden and those are Marianne Williamson and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

The committee has effectively boxed them out from all media coverage. I feel like if there were more competition in the primary, we could actually hold our Democratic Party candidates to actually discussing climate matters. Right now, we have a better-of-two-evil system. I know a lot of people feel that way about our two-party system. If we actually have a proper Democratic Party primary, we could actually hold our Democratic candidate to being more active in the climate agenda.

Brian Lehrer: Let me follow up with you, Aaron, and get your take on this. Another way to look at the Democratic primary field right now is that Marianne Williamson and RFK, Jr., are fringe. They're not getting a lot of media, not because the Democratic Party infrastructure has blocked them out, but because there's reason not to take them as viable challengers to Biden. That's the same reason this argument would go that no bigger-name Democrats are getting in because they just think they'll lose. That's the state of the Democratic primary right now, but tell me if you disagree.

Aaron: The voters, I think that it's necessary to allow free and fair elections. I believe all information has to be available for voters to make informed choices on who they vote for. The Democratic Party has an imperative to allow voters to decide who to vote for and not have a predetermined choice, almost like a coronation. There has to be an election. We have to have a full-throated democracy and not just choose one candidate to go against the Republican Party because, at that point, who's going to hold him accountable for climate action? There has to be some conversation.

Brian Lehrer: Right, I'm just asking who's choosing. It seems like the Democratic primary electorate doesn't have interest. Even though they have interest in theory in having somebody younger, those people who would get a lot of votes aren't stepping up.

Aaron: I disagree. I don't think it has anything to do-- it does not reflect on the interest. It reflects on the willingness of major media corporations to host these other voices, these challengers, and to properly display their agendas and let them voice their ideas. I think if they actually were given a platform, you would see these numbers go up. They are reaching poll numbers that previously would qualify them to debate, but there are no debates. Joe Biden has declined to debate them. I think this is a failure. Effectively, we're not really holding his feet to the fire as far as climate policy.

Brian Lehrer: For good policy. Aaron, let me--

Aaron: Okay.

Brian Lehrer: Right, because there's no competition pushing him to a more progressive spot. Aaron, thank you for calling us. Keep calling. Where do you think, Rebecca, that activism, short of a Democratic primary, which might not happen apparently, but where activism might fit into 2024 politics? America saw on TV last week, news coverage of the three activists who held up the US Open tennis semifinals for almost an hour, including one who glued themselves to the ground. Good politics or what bigger picture role next year for the activist community on climate?

Rebecca Leber: Yes, I think protests and activism is certainly shifting to reflect that this is not an open primary year. We saw a lot of focus from US environmental groups the last cycle in pressuring the front runner at the time, Biden, into coming out stronger on his climate platform. The dynamics of this cycle, as your caller was mentioning, are certainly different. They may have some less leverage in a way, but I don't think that means they have no voice here because Biden is certainly worried about engagement and enthusiasm in his re-election prospects.

He really needs to maintain support to have a chance at re-election. His record on climate is hugely important to that because we see in polling that while the Republican base may not be very interested in climate change issues, Democrats rank it really highly in priorities. When you look at issues like the economy, health care, immigration, climate change is really high up there as well. Biden wants to prove that he has a strong record here.

Brian Lehrer: Especially with young Democratic voters for turnout. Let me get a comment from you before you go on. The other climate story from this week that I mentioned in the intro, the UN declaring the 2015 Paris Climate Accords are not meeting their goals. What did the UN say?

Rebecca Leber: This might sound like just another climate report saying that we are far off-track to meeting our climate change goals, which it is in a way, that this was a scorecard issued. It was mandated by the Paris Agreement issued in 2015 that the world assessed how much progress it's made on meeting about 1.5 or 2 degrees in climate change that they assessed the country's goals and commitments so far and see how much further we have to go on. The bad news is we have a long way to go. The good news is there has been progress made. Part of the process of this stocktake is to urge more action.

Brian Lehrer: Just real quick, did they single out countries, India or China, like Nikki Haley did in that clip, the US despite the biggest climate policy bill ever from Biden and Congress that Haley was opposing in that clip? Anybody?

Rebecca Leber: No. What's important here is that this was a technical scientific assessment that will play into the politics come November when the world meets for its next climate conference in Dubai. That's where the politics will really come in of seeing how much countries need to step up to contribute to climate cuts.

Brian Lehrer: Rebecca Leber covers climate change for Vox. Thank you so much for joining us on our Climate Story of the Week.

Rebecca Leber: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.