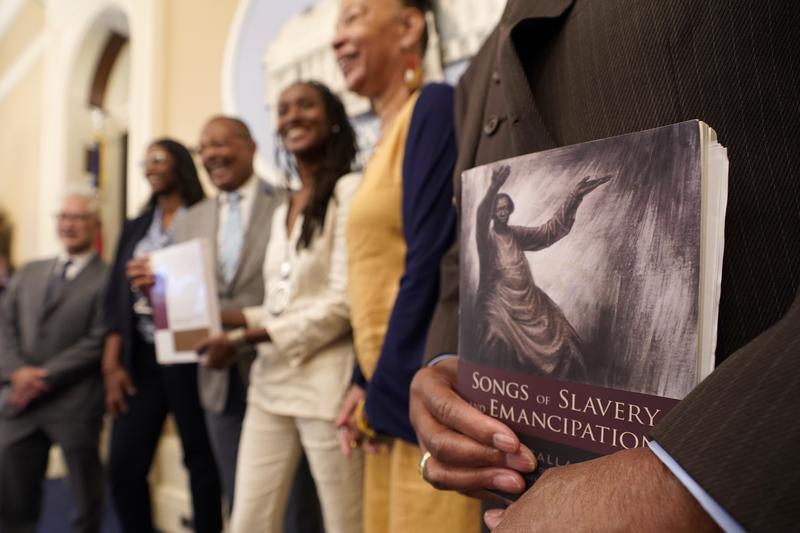

California's Reparations Task Force

( Rich Pedroncelli, File / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. I don't know if you've heard this yet, especially if you're not in California, but California is exploring the question of reparations. A task force will make recommendations next year to Governor Gavin Newsom on a plan to compensate African-American state residents for the economic legacy of slavery and racism. It'll be up to lawmakers in the state to act on those recommendations, but just the fact that they're looking at them with an official group is a big first step.

We'll talk now about the task force's work so far, and why California, which only gained statehood about 10 years before the start of the Civil War and wasn't officially a slave state, is even considering reparations for slavery and leading the way in a certain respect on that. We'll talk about how much of the state's resources would even begin to feel like historical redress.

Joining me now is Kurtis Lee, Los Angeles-based economics correspondent for the New York Times. Kurtis, thanks for coming on with us. Welcome to WNYC.

Kurtis Lee: Brian, thanks so much for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Who's on the reparations task force, and what has Governor Gavin Newsom asked them to determine?

Kurtis Lee: The reparations task force here in California, I think we should first step back obviously to 2020. After the murder of George Floyd, we saw a lot of social justice protests around this country. We saw a lot of companies, colleges, city and state leaders calling for racial justice. Lawmakers in Sacramento have to build- it basically would create a nine-member task force to explore reparation in the state of California for African-Americans and Black citizens obviously.

It's a mix of people on this task force. You have politicians, you have academics, you also have lawyers and historians and people who just really have obviously studied reparations, the history of this country. Basically, they've been just really exploring reparations and traveling the state, hearing from residents who have suffered from discrimination, whose families might have locked land here in California due to racist policies.

They've been holding these town hall-style meetings from San Francisco to Los Angeles and Oakland, really hearing from the community, hearing from residents, and really coming up with an idea of what reparations could possibly even look like in the state of California before they then move it on to a final report they will pass along to lawmakers in Sacramento to basically come up with a concrete plan that the legislature would eventually have to pass.

Brian Lehrer: Have you been to any of these town halls as a reporter and heard any individual stories? Maybe pass one example along here, because we can talk about slavery and the horrors of slavery and how the economics of slavery affect people to this day in the abstract, but when we hear a person's story, sometimes it hits home in a different way. Do you wake up at night thinking about any of them?

Kurtis Lee: Of course. I went to a meeting here in Los Angeles in September, and you hear these terrible tragic stories of loss of people who are just really sitting with a lot of pain, Black folks sitting with a lot of pain in this state. Reading the report, the committee came out with an initial report this summer that really outlined some of the tragedies of slavery and racism here in this state. A lot of enslaved Black people were brought to California during the Gold Rush era. The report gets into how redlining and obviously racially restrictive covenants had segregated Black Californians in some of the state's biggest cities.

When you look at what happened in the Western Addition in San Francisco, the Fillmore District, this was a vibrant Black neighborhood in San Francisco. This was the Harlem of the West, they called it in a lot of ways. City officials had designated this area a blight eventually in the '50s, '60s, and '70s. A lot of homes were demolished, a lot of Black-owned businesses were demolished and people were pushed out of San Francisco, Black people. What really also stuck with me was the story of Russell City, California. It's this community in the East Bay, in the Oakland Alameda County area.

This was a community that was a vibrant Black community where people fleeing the deep south during The Great Migration heading west to Los Angeles and Oakland and the Bay Area, settled in this civil community, Russell City. It was an unincorporated part of Alameda County, and basically, the county eventually designated this area a blight. They said that there wasn't running water, there wasn't reliable electricity, but it was home for a lot of people. It was a vibrant community.

There was blues clubs, there were a lot of people sitting on porches reminiscing about their lives that they had fled in the south and now their new work that they were doing in shipyards in the West. Eventually, county officials said this was a blight, people need to leave. They started seizing a lot of properties through eminent domain. People who had paid decent money back in the '50s, '60s for their homes, were given nearly a fraction of what they had paid and forced to move. A lot of people were relocated into parts of Oakland, into Hayward, and further outside in the Bay Area.

Just hearing the stories of tragedy, of loss, of generational wealth loss. When you look at the median wealth of Black households in the United States, it's $24,100 compared to $188,200 for white households. When you really talk about generational wealth and you look at the history of racism in this country, it really has a lasting legacy, and I heard that through those stories in Russell City when I talk to people.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for those examples. California listeners, if you're up early and listening to [unintelligible 00:06:25] Radio, our lines are open for you. What should your state take into account as it considers the question of reparations? Or anyone else, because this really is a national question. It's just that California hasn't paneled this task force now.

What should the country take into account as it considers the question of reparations? What could any state at the state level, even a state as huge as California, so much bigger than any other state in this country of 40 million people?

212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer, with Kurtis Lee from the New York Times, who's covering this as an LA correspondent. How does the task force think reparations would be distributed and how has the task force, if they've gotten this far yet, suggested that it would determine eligibility?

Kurtis Lee: The task force is looking at a number of ways that reparations could be implemented. I should note that, obviously, California is the first state in this country to do something like this, to create a reparations task force. This has not happened at the federal level in Congress. For almost 30 years, John Conyers, the former representative from Michigan was really pushing this bill called HR 40 that would essentially create a federal task force to explore reparations.

Since Conyers retired and obviously passed away, Sheila Jackson Lee in Texas has taken over this legislation in Congress. It said it passed out a committee for the first time in 2021, but eventually, it stalled on the floor of the house. Again, California is very much the first state to do this, but they've also looked at other examples of what cities have done. Evanston, Illinois. [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Can I jump in on that for just a second, the Congress piece?

Kurtis Lee: Yes, of course.

Brian Lehrer: Even with the Democratic Congress, the last few years, they couldn't get this famous Conyers' bill, which we've talked about on the show. Unfortunately, we never had him during his lifetime, but it wasn't going to commit anybody to anything, it was just going to study the question, and they couldn't get that through a Democratic Congress?

Kurtis Lee: There was a lot of pressure, obviously, from groups like the NAACP really calling for Congress to step up. Yes, you're absolutely right. After the momentum that was felt, after 2020, after George Floyd's murder, after this "racial reckoning" that this country was having, even Democrats were really pressed on this issue. You see people like Cory Booker, who was very vocal and supportive of this measure, speaking to the White House, to the Biden administration.

There was movement though. It passed out of committee for the first time but eventually, it stall. Absolutely, even with Democrats in power, it's been tough to get this bill passed. Obviously, California has essentially replicated what HR 40 is on the federal level, basically at the state level here in California.

Brian Lehrer: You were starting to say, before I so rudely interrupted, that there are some smaller examples out there at the city-- [crosstalk]

Kurtis Lee: Yes. You see it in Evanston, Illinois, recently. Officials there approved $10 million in the form of housing grants being rolled out in terms of reparations. Also, in Asheville, North Carolina, city leaders have committed 2.1 million toward reparations. These are obviously smaller places, cities, and it's nowhere near the level of the state of California but back to the task force in California, they're looking at a number of ways to implement reparations.

This could be also through housing grants, it could be through direct cash payments to residents. Again, a lot of this is up in the air in terms of what the legislature does with these recommendations that are given to them next year from this task force, and is there the political will to do anything? Will they move ahead and actually pass legislation that offers concrete payments to Black residents? It's still all very much up in the air.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. I guess what kinds of forms it would take is a fascinating rich topic of conversation. For example, Cory Booker, who you mentioned, some of the listeners may know, that he's famous in this arena for his baby bonds proposal, which is for basically every baby in the United States, regardless of race, to be given a certain amount of bond credit or whatever you'd call it, that would mature when they get to be 18 or so.

There would be equality in, let's say, the ability to afford to go to college, which so distributes by race in this country because of the legacy of discrimination in this country. That's an example. I don't know if I got all the details exactly right but that kind of thing with Cory Booker's baby bonds.

Kurtis Lee: Absolutely. In terms of Booker, he's been a vocal supporter of the reparations and he's obviously, like you said, been out there with his effort for baby bonds. Also, lawmakers, the people I talk to here in California, they want to see this as this catalyst to really spark a fire under other states as well, possibly, lawmakers in Albany and in New York looking at something similar to what California is doing.

They really want to use this as a catalyst to create this dialogue in this country and not just let what occurred in 2020 after George Floyd dissipate. They really want to create a catalyst for this to move on for there to really truly be some racial justice in this country in these years ahead.

Brian Lehrer: TK in the Bronx, you're on WNYC. Hi, TK.

TK: 40 years ago, my grandmother left the Bronx and moved to San Francisco. She had a nice home in the Bay Area. I was about 10 years old. I can remember the whole neighborhood, Black, the whole neighborhood. We could go out on the porch. I could see the Golden Gate Bridge from my grandmother's porch. 20 years after that, she said, "We got to go. We were told we got to go." I said, "Grandma, who told you, you got to go?"

She said, "The people over here are saying we can't stay here, and they keep raising up my taxes. They keep raising up everything, my water. I can't stay here." She moved from there to Georgia and she ended up passing away in Georgia. If I go to that same neighborhood now that I grew up in then, there's not one Black family in that neighborhood. That neighborhood was all Black, all.

They have moved us all over this country and taken away houses time after time. We build it, and for some reason, it gets taken away time after time after time. That's my story, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: TK, thank you for sharing it, and keep calling us. In fact, Kurtis, if I'm seeing it right on housing discrimination specifically, and you can hear the multi-generational emotion in TK's voice. On housing discrimination specifically, you write in your Times article, the California Task Force estimates compensation of around $569 billion. Do I have that right? That's just for the years between 1933 and 1977. How did it arrive at that figure?

Kurtis Lee: Absolutely. That's been in these discussions that the panel has been having with economists and different experts on reparations. California, like you said, has nearly 39 million people. Nearly 6.5% of California residents are Black. That's around 2.5 million, people who identify as Black or African American here in the state. These are all preliminary figures.

These are just in-the-discussions and estimations of what it would cost just for this one area. This task force has identified several areas so far where they would look at implementing reparations. That number, in this area, can rise, it can be reduced. Some of the areas they're looking at are obviously housing discrimination, that's incarceration, unjust property seizures, the devaluation of Black businesses, healthcare.

Like you said, there is this number that's being floated out there, this $569 billion but, again, this is all very much just in the form of discussions. The task force has not officially recommended any of this. All of that will continue to be hashed out in a final report that'll be released in 2023, and then it would be on lawmakers in Sacramento to pass or not pass different forms of reparations in the state.

Brian Lehrer: This is WNYC FM, HD, and AM, New York, WNJT FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are on New York and New Jersey Public Radio and live streaming at wnyc.org. Few more minutes with Kurtis Lee, New York Times correspondent in Los Angeles, who has an article about the first-in-the-nation state-level reparations task force studying the idea of reparations for 400 years of slavery and other racism at the state level in California that's going to report back to Governor Newsom and the state legislature there next year and is possibly setting a model for what may be taken up next in other states.

Let's take another call. Beverly, in Savannah, Georgia, you're on WNYC. Hi, Beverly.

Beverly: Hi, Brian, thanks for taking my call. I love your show. I basically have been listening to these arguments for quite some time now and horrified at the unfortunate situation that we're in to have to be dealing with the very same fixed system that caused the atrocities and is perpetuating the atrocities. I think it's very important, obviously, to deal with the after-effects and the reforms but those cash payments should be made according to what was owed the ancestors of Black people.

The slaves were owed for their labor and their descendants should definitely be paid in cash. The reforms are necessary, but they should be separate. Otherwise, we'd just be perpetuating the situation where we're in centralizing a segment of our population and pretending that they're not entitled to spend what's owed to them, to spend the legacy of their ancestors as they see fit. The reforms for the society have to be separate. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Are you saying the reparation should be limited, because some people say this, "To actual descendants of actual American slaves"?

Beverly: No, I'm saying that reparation, as a term, has been muddied over all this time. Obviously, the descendants of those slaves are owed their legacy. Because all of these atrocities have been perpetuated through our society, there has to be reforms-- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Right. I see. You're saying baby bonds are not enough, civil rights laws are not enough, the actual cash that, in effect, has been stolen with the interest taken into account should be returned?

Beverly: Absolutely. Else, we're just not getting to the root cause. Else we're implying that Black people aren't entitled to what's owed to them. Else, we're implying that people have to spend their money for them because they just can't do it for themselves. The reforms are necessary for the society, obviously. When you let a problem fester for centuries, obviously reforms are necessary but the reforms alone are not sufficient.

Brian Lehrer: Beverly-- Go ahead.

Beverly: Frankly, I believe Blacks should be tax-xempt as well.

Brian Lehrer: Should we-- Sorry, you broke up there. The last thing you said was you also believe what?

Beverly: I believe that descendants of actually Blacks should be tax-exempt as well. It's a combat pay. American society, whether people are ready to admit it or not, is a gauntlet for Black citizens. I think we need to be protected much the way endangered species should be protected. We're not getting to the point. I know that politicians want to do the most that they think can be agreed upon, but we're just pushing-- we're just kicking the can down the road if we don't pay those reparations for the actual slavery to the actual descendants.

Brian Lehrer: Beverly, thank you so much. Please call us again. Alan in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Alan.

Alan: [unintelligible 00:21:00] voice, I apologize. I think we have to do with this something alike to what we need to do with COP27. The funds for loss and damage, not just focused on who is entitled to be compensated, but focusing the source payments on those most responsible. If we only talk about general revenues funding these compensation funds, you're going to scare away many low and moderate-income whites who would otherwise support the idea as justice because they're going to be afraid that they're going to be asked to pay an unfair share of problems that they have no role in.

Brian Lehrer: That's really interesting, Alan. Thank you. Is the task force dealing with that? We're almost out of time Kurtis, but Alan raises an interesting question there, which is, who pays if California comes up with a reparations bill from this task force? Should it fall on the general fund taxpayer or people who somehow have benefited more, however that's measured?

Kurtis Lee: That's where some of the pushback obviously in Sacramento came when this bill was presented in 2020. You saw, obviously, there was a lot of Republican pushback. Some Republicans, obviously, voted against the measure to create this task force and cited how the state would pay for this, would this be from taxpayers? There were concerns on that front.

Even at the local level, with some of these smaller efforts, there's an effort in Hayward, California, I mentioned Russell City, that was annexed by Hayward. In 2020 last year, the city of Hayward offered a formal apology to residents of Russell City and also created a smaller task force that's very local, that will look at reparations for descendants of Russell City. These couple of hundred people who-- several hundred people, who had lost their homes.

There was local pushback basically saying that this is a "era of social justice," and that this is not well thought out. People shouldn't have to- who weren't even living in the community then shouldn't have to essentially be a part of funding any reparation. There definitely has been pushback. All of this remains to be seen as we move into 2023 with the final recommendations that this task force will present to the state lawmakers here.

Brian Lehrer: On that, last question, how serious is Governor Newsom about taking actionable steps toward reparations once the task force completes its work? I think it's already clear they're going to come up with some recommendations for some reparations. We know that so many of the promises made by institutions and corporations in the so-called racial reckoning era post-2020 have gone unfulfilled.

Kurtis Lee: That's a critical question. When Newsom signed this bill in 2020, he released the statement really applauding it and encouraging the task force to get to work. He lauded this as a moment of reckoning in this state. Like you said, fast forward a couple years later now, what will the political wins look like? Is there still a vested interest from a rising Democrat in the party to really push forward with reparations? I think that remains to be seen in these months and years ahead.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, is he getting ready to run for President? We did a call-in this week for Democrats asking them if they want Biden to run for reelection or not, and a lot of them did, but among those who didn't, several mentioned Gavin Newsom as an alternative. Is he laying the groundwork either for that, if Biden doesn't run, or for 2028, if you can look even that far ahead?

Kurtis Lee: I think that, obviously, Governor Newsom is definitely a rising star in the party. He's had this elevated level of support in the party from people who are looking for an alternative to President Biden. He, earlier this year, went around Washington and did a tour meeting with lawmakers on Capitol Hill and just really just putting himself out there more. He fits a recall election last year here that he won and really revitalized him and really pushed him more to the national stage. He insists, obviously, that he's supporting President Biden should President Biden run in 2024. I think a lot of options are on the table for Governor Newsom.

Brian Lehrer: Kurtis Lee, New York Times correspondent in LA. Thanks so much for getting up early and doing this with us. Really grateful.

Kurtis Lee: Hey, thanks so much for having me, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.