Back to School COVID Update

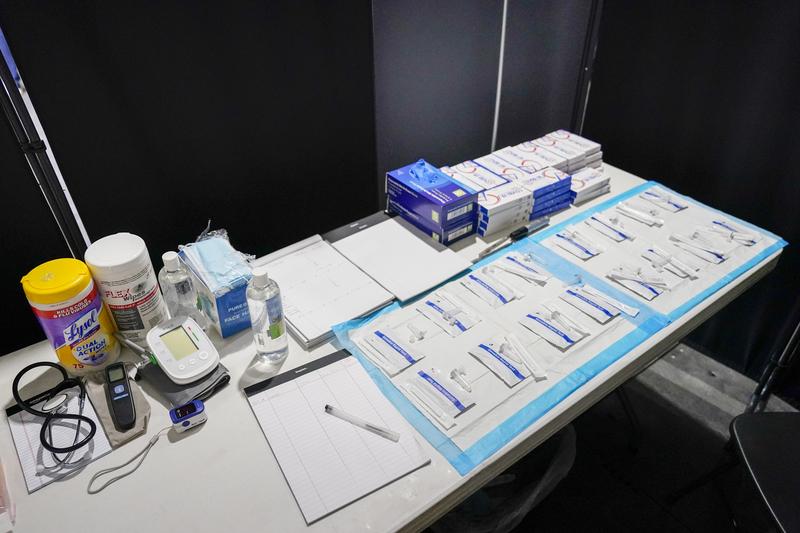

( Mary Altaffer / AP Photo )

Announcer: Listener-supported, WNYC studios.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Hope you had a great Labor Day weekend. Hope you had a great summer. If you're out there because you're getting back to local radio today after being away. For the parents of school-aged kids listening right now, maybe it's a sigh of relief as you pack the kiddos off to school again and let someone else deal with them for much of the day, right? Don't send them to school if there is no school. First day of school is a real patchwork around here. Here are some examples of how much so.

New York City public schools begin on Thursday. New Jersey is all split up. New York begins today. Jersey City, Thursday. Elizabeth, not until Friday. Even within the same area, we can have some differences. I read that school starts tomorrow for the Freehold Regional High School District, but on Thursday for the Freehold Borough School District. You 07726 zip code, folks don't go back the same day as the 07728. Looking at the Westchester map, just some examples, Ossining and Irvington today, New Rochelle and Katonah tomorrow, Mount Vernon and Yonkers on Thursday.

On Long Island, most of Nassau County, today, with some opening tomorrow. Carle Place, Elmont, Jericho, all tomorrow. East Williston on Thursday. Suffolk County is more split up than Nassau, so don't send your kids to school unless there is actually school is the bottom line on that. For you teachers, I know you're basically all back for prep, whatever the kids' show-up date is. Good luck out there parents, teachers, students, and staff.

We're back to real summer heat around here today, and most of this week, maybe all of this week. Highs in the 90s coming for the next number of days. Later this hour, we'll have our climate story of the week as we're doing every Tuesday, all this year on the show. Today we'll specifically break down the numbers after the hottest June and July on record globally and the single hottest day on record, which came earlier this summer. Global warming by the numbers as the summer of '23 nears its end coming up.

We'll also have a call in at the end of the show on how your garden did this year, what grew Well, what didn't? I know some of it's still growing. What are the long-term trends in the news from your own backyard coming up later. It's also a new season, sorry to say it, for COVID. Did you see the White House news on that this morning? First Lady, Jill Biden, just tested positive. We'll see about the guy she sleeps with. Later in the show, we'll have Franklin Foer from the Atlantic who has a new book about the Biden presidency as we head for real into the 2024 election cycle.

Biden gave a Labor Day speech yesterday in which one of the notable things to my ear was that he took a few specific swipes at Trump, something he often has tried to avoid, indication of election season coming more full swing. On COVID, a graph showing daily hospitalizations with COVID in New York City from the City's health department shows a tripling from early July through last week from the high teens per day as summer started now more than 60 per day being hospitalized according to the Health Department's data chart. With a new variant, BA.2.86 spreading here now, and the updated vaccines still a few weeks away from release and availability. COVID is back and a back-to-school story too.

Let's talk about the COVID news first. We'll touch on RSV and maybe a few other things too as time permits with Dr. Daniel Griffin, MD PhD, chief of infectious disease at ProHealth, researcher at Columbia, president of the group Parasites Without Borders. That's how Republicans see asylum seekers, but this is not about that. Dr. Griffin is a regular on the podcast This Week in Virology. Dr. Griffin, always good of you to give us your time and expertise. Welcome back to WNYC.

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Now, thank you. Thank you, Brian. Thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Jill Biden, are you surprised the first lady just got COVID with the precautions that are taken typically to protect the President of the United States and presumably his wife?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: I'm not surprised, and this is, I believe not her first time testing positive with COVID. I saw that news this morning. Maybe there's something sobering here about the fact that COVID is here to stay. I sometimes joke with my patients, "Have you been breathing?" That's all it takes. There's no character flaw. This isn't something the Secret Service can keep people safe from.

Unfortunately, as we all know, individuals who seem fine, who have no symptoms, they can be exhaling SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. If you are there long enough and you breathe that in, and particularly if you're within that 3 to 6 feet persons talking, they don't even need to be coughing, and we see transmission.

Brian Lehrer: Do you think it's a sign of people generally letting down their guard when we had such a low COVID period in late spring, early summer? Again, it's not a judgment on anybody's character, as you say, but I wonder if they have the required testing before being in the company of the first family as they did earlier in the pandemic?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: That's an excellent question. I certainly don't know the details of how the president and his wife are handling possible exposures, but the mentality has changed. There was a point in time when everyone was getting tested every day. Well, almost everyone as we later learned, but most people, at least that was supposed to be the approach. As we've all seen is people are growing tired of testing. There's a bit of COVID fatigue. Part of this, I'm going to say, is reasonable and warranted. Part of it we also have to continue to be intelligent about but multiple vaccinations, ready access to early antiviral treatment. When you put those two together, we're in a very different situation.

Most people at this point have some degree of immunity, whether it's from prior infection or vaccination. Big difference now is who's getting offered treatment. I was surprised. Jill Biden actually looks quite young, but she is in her 70s. That does put her in a higher risk situation. I think this is something that we'll need to follow, but hopefully this gets people starting to think COVID is out there. If you're trying to make decisions, you're an older individual, maybe you have medical issues, you're trying to decide, "Should I go to that crowded indoor restaurant?" Okay, maybe now is not such a great time to be thinking about doing that.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, your questions are welcome for Dr. Daniel Griffin on the new wave of COVID or other infectious disease questions. We'll try to touch on RSV, for example, maybe even some others. Are you seeing those RSV vaccine ads all over television now like I am? Folks, 212-433WNYC, with your COVID and other related questions for Dr. Daniel Griffin. 212-433-WNYC, call, or you can text us at that number. Remember, 212-433-9692. You can also tweet @BrianLehrer. I read those hospitalization graph numbers from the New York City Health Department. That's one indicator. How would you describe in other ways the extent of the uptick we're seeing now in the greater New York area?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: No, Brian, I think it's great that you mentioned the data that we have. We don't have data on everything. We have data on hospitalizations, we have data on deaths. We really, several months ago, lost the ability to know how many cases, so sometimes we'll ask urgent cares or testing centers, "What percent of those tests are you doing that are positive?" A lot of people are testing at home not reporting that. A lot of people are not testing at home, not reporting that. Those are the numbers we have.

That's actually what we're seeing. We are seeing that the hospitalizations are increasing, and it's not just people who test positive, it's people who test positive and are in the hospital because of COVID. We are seeing 500, 600 COVID deaths a week. You start multiplying that we're getting still in the tens of thousands of deaths, and we expect that to increase on a yearly average.

Brian Lehrer: What is that number, the hundreds of CO-- give that number again, and is that a national figure or a local figure?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes, that's currently the national figure. It's about 500 to 600 deaths per week from COVID, so we're actually a little bit lower than we've been in the past. A challenge, and I think this is really important to point out, is a lot of those deaths are actually, I'm going to call them, silent deaths. Deaths in nursing homes, deaths in facilities, deaths in older individuals who test positive are not offered treatment, don't end up in the hospital, don't sit in an ICU where we see them every day. They're quietly dying in these facilities.

Brian Lehrer: You touched on something that I wonder if you could elaborate on the difference between hospitalizations with COVID and hospitalizations from COVID. You know what I'm talking about?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: No, I think it's an important distinction, and it's important to be very honest and I think transparent about this. There are individuals who are-- maybe they're in the hospital for some other reason. They twisted an ankle, they have a femur fracture, they have a urinary tract infection, whatever it is, and now it's time for them to go to a facility. A lot of facilities require we test them. They get a test, it comes back positive. Now, that person has no respiratory symptoms. They have no fever.

They have no illness, no COVID-19 illness, but they have a positive test. Also, have people where maybe that's the scenario when they hit the door. There clearly is a distinction between people with the disease, COVID-19, and people who just have a positive test.

Brian Lehrer: What is BA.2.6, and why does it have the nickname Pirola, P-I-R-O-L-A, this new sub-variant of Omicron?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: We're supposed to not use those nicknames, so this is what I hear. It's really hard. I have to say I even have trouble keeping track of this alphabet soup. What is happening over time, and what continues to happen over time is, the virus evolves. It's under a certain amount of pressure. Now a lot of that pressure is an immune pressure. It's under pressure to become immune evasive to re-infect people that have been infected before, to infect people that have been vaccinated. There's no pressure on the virus to be less virulent. Most of the transmission occurs in the first 5 to 10 days, almost all of it within the first 5, almost all of it within the first 10.

The pressure is the ability to continue to infect people that have been infected before, people that have been vaccinated. Over and over, there's always early data, early speculation about, will this be more or less severe than prior variants? We're going to continue to see variants and this is going to be an important issue for us to track when that question comes up, who should get boosters? Are the boosters going to make a difference, in the coming weeks?

Brian Lehrer: I'm seeing again from the New York City Health Department, basically, they think everybody should get the new booster when it's released, probably later this month. Would that be your advice or is that your understanding of the public health messaging we're about to see?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: I think there's two messages here. There's the public health message, which is the more people that get the booster, the more of an impact we have from a public health perspective on the disease. A lot of people in that physician-patient interaction, they'll ask, "Well, what about me? I'm not as altruistic as the public health folks would like me to be. What about me?" Now, if you're an individual over the age of 50, and I'm over the age of 50, you have a non-zero risk of a bad outcome. Getting that booster for probably three to four months will reduce your risk of even getting infected.

The superpower we talk about with vaccines, because vaccines are really there to prevent disease, and that 90% reduction disease is durable. You're in your 20s, you're in your 30s, you've already had three or four vaccines, maybe you had a prior infection. This is going to be a slightly different discussion as far as your personal risk-benefit if we're not talking about how do you help out your community, your parents, your friends, your loved ones, your coworkers, et cetera.

Brian Lehrer: You say risk-benefit. Are there risks?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: [laughs] As far as the vaccines are incredibly safe. I don't think we've-- well, I will say we have never had vaccines that have been under such close scrutiny. These are incredibly safe vaccines. Some people they feel crummy for a day or two and maybe feeling crummy for a day or two is a price they're not willing to pay to protect their family and friends. I joke, the only side effect of my vaccine was I actually felt a momentary period of frustration. It was right after opening an email from one of my colleagues. I'm sure it had nothing to do with the content of that email

Brian Lehrer: Listener tweets a question for you, "Do you have an opinion regarding the safety and efficacy between Pfizer, Moderna, and Novavax COVID-19 vaccines as it relates to the BA.2.86 variant?" Thank you very much. Writes to this listener, and I note from within that question that the company Novavax is back in the conversation now. We've really only talked about Pfizer and Moderna for so long, Johnson & Johnson at the beginning of the pandemic, but suddenly there's a Novavax vaccine coming out now, as I understand it, that also it's being talked about in this country. Yes?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Brian, I think that's great, and thank you for tweeting in that question. It's good that people are aware. There are options out there. There are three options. Here in the US there's the Moderna vaccine, there's the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, there's the Novavax, which is this, some people would think of it as, more traditional protein-based. All excellent vaccines, all excellent efficacy. A nice thing here is if maybe you didn't tolerate one of the earlier vaccines particularly well, now you can think about another option. I would say all three are very safe, very well tolerated, and all the data we're getting is effective as boosters.

Brian Lehrer: Effective as boosters for BA.2.86? I don't know if that's been tested. Has it?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: [laughs] You like to ask the hard questions. That is the challenge. We just heard, well, this last week that some of the manufacturers, the mRNA vaccine manufacturers, have submitted data to the Europeans. I haven't seen that data, I actually like to see it myself, suggesting that we're going to get that three to four-month boost in neutralizing antibodies, that there will be some three to four-month benefit. The challenge is going to be as we get into November, December, January, the peak of it, what will the variants be then predicting the future. Hardest thing to do, Yogi Berra tells us, and will we get those neutralizing antibodies? Will we get that three to four-month boost?

Brian Lehrer: It's the hardest thing to predict. I love that quote, by the way. I was just thinking about that quote in another context related to the show over the weekend. He said, "Yes, the future is the hardest thing to predict." Anyway, go ahead.

Dr. Daniel Griffin: No, no, no. He didn't say half the things he said.

[laughter]

Dr. Daniel Griffin: That's the big challenge. We are hoping that these boosters, and again, we're trying to predict now, and that's why it was based upon an XBBB monovalent. We will see. We'll know after the fact sometimes flu, that's another example of where we know after the fact. We try to guess, we try to predict, we come up with a formulation and then we'll see. Right now, everything we're hearing is positive. Are we hearing about efficacy about FL.1.5.1 or hear about the Eris, the EG.5. We're starting to get some supportive information and it will continue to come.

I think we'll have the data in time. The vaccines here in the US are not available today. The boosters will be available end of September or October. Actually, from a timing, is one of the first years that the CDC is starting to give guidance on timing of vaccines. They're doing that in the context of flu saying, "Don't do it too early." We're talking about a three to four-month boost protection. Most of us are advising if you're going to go ahead with the booster, it's going to be October-- end of October, early November is probably the time to be thinking about your flu and your COVID vaccine.

Brian Lehrer: Although a few people recently brought up a timing to me as, "Hey, school is starting now. There's going to be so much more congregating by kids and kids exposing their teachers, et cetera, and their families at home. Why isn't the booster timed for the start of school?" Is that a question you've ever thought of?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: No. It's an excellent question. It comes up with the issue of how often can you reasonably boost. If you could boost and get a shot every three months and just keep that at that super high level, okay, that's one public health strategy. You start to ask too much. If you boost now, then you've got protection for, let's say, September, October, November. By the time you get into December, January, it's really starting to lose its effectiveness. Do we boost again in December? For certain patient populations, that is not unreasonable, but for a broad public health perspective, you are starting to ask too much. If you ask too much, people are going to start saying you're asking too much of me.

Brian Lehrer: We have other COVID questions from me, from listeners, many questions coming in via our various means. I want to start folding in RSV to this conversation and take our first RSV callers. Gregory in Harlem, you're on WNYC with Dr. Daniel Griffin. Hi, Gregory.

Gregory: Hi. Good morning, Brian. Listen, I have been in a test of the GlaxoKlineSmith or SmithKline. I have been tested for the RSV. I heard recently that there was one [crosstalk]--

Brian Lehrer: Sorry, just to be clear. Does that mean you're a subject in the trial for the RSV vaccine?

Gregory: Correct.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you.

Gregory: Yes. It's been going on since-- actually before COVID. Now, I'm in my third year still feeling healthy. I'm 77 years old and I'm good. I just wanted to say that I'm hoping that we will have one for people like me coming out soon.

Brian Lehrer: Gregory, thank you very much-

Gregory: What is the doctor's-

Brian Lehrer: -for that report? Do you have a question besides telling us that story?

Gregory: Well, I just wanted if the doctor knows anything about any of the other trials that are going on and whether or not this is the only one and so forth.

Brian Lehrer: Thanks, Gregory. Thanks so much. Dr. Griffin?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes, Gregory, happy to jump in here. Thank you for sharing that. A lot of people, what is this RSV or as my mom always spells it, she's got the letters but in various different orders depending on the time she calls me. RSV people probably know from children. About 20% of children at some point will get a really severe case of RSV bronchiolitis lung infection requiring medical attention. We actually get a lot of cases in older adults and by older, I'm going to say 65 and over. 60 to 160, about 100,000 hospitalizations every winter. We probably get about 10,000 deaths every winter.

It's a pretty significant disease for filling our pediatric hospitals. Pretty significant disease for getting older folks in the hospital. If an older individual gets admitted with flu versus RSV, the RSV likelihood chance of not surviving is about twice the death rate, twice the chance of not surviving that hospitalization. Pretty significant issue, and there are a number of vaccines that have been through trials and actually this fall and are starting to hit the shelves in some parts of our country. There will be RSV vaccines. GSK, Pfizer's, a couple of different companies in the game. These vaccines are going to be recommended as a shared clinical decision with a physician and a patient.

Now, just what exactly does that mean? We're looking at vaccines that have in the clinical trials by a 90% reduction in ending up requiring to see the physician, requiring a medically attended lower respiratory tract infection with RSV. The trials were only about 30,000 people in each trial. We haven't seen those big rollouts that we saw with the COVID vaccines where we start to find rare side effects. At this point, the recommendation, if it's a high-risk individual clearly even if there's a very rare side effect, that side effect from our trials we anticipate being much lower than their risk of going into another season unprotected. By the way, these may actually protect for more than one season.

On the other side, someone who's right on the fence, maybe this individual's 66, they have no medical problems, they're thin, they're healthy, they exercise. For them, they're at much lower risk. They may want to wait. They may want to see what happens with the post-marketing surveillance. A couple of vaccines for those older adults. One of them is also authorized for the last trimester for a pregnant individual to then pass that protection onto their little kids. Then there's even a monoclonal for the little kids.

Brian Lehrer: RSV, remind us the initial stand for?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Respiratory syncytial virus.

Brian Lehrer: Syncytial means?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Basically a lot of cells connecting a syncytia, becoming the same cell. It has something to do with the way the virus interacts. COVID does that too. It can create these syncytia where it actually causes multiple cells to come together and form one large syn or same cell.

Brian Lehrer: You talked about trial. Just to be clear, I mentioned in the intro that I've been seeing RSV vaccine commercials all over television at least on-- I watch a lot of news. I watch my share of sports although Spectrum blacked out the US Open this weekend because of their contract dispute with Disney. News and sports at least, and probably a lot of other things showing RSV vaccine commercials. That means it's beyond the clinical trials point, right?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Oh, no, it is out there. Yes, Brian. We have Arexvy by GSK. We have ABRYSVO by Pfizer. These are out there. Those are already hitting the shelves in certain parts of our country. These are going to be available all around the country. Recommendation here is, go ahead as soon as it's available because as I mentioned, this is not just a three to four month. This is probably going to be at least a two-year protection. Well, some of us had the ability to look at some of that two-year data which continues to be very robust. This is out. This is already something people should be watching and trying to schedule their appointments.

Brian Lehrer: So many new COVID season questions coming in. We'll continue with Dr. Daniel Griffin and your questions right after this.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. We're talking primarily with Dr. Daniel Griffin about the new wave of COVID hitting our area and hitting the country. I mentioned in the intro before the data from the New York City Health Department which shows hospitalizations in New York City of people with COVID have tripled from early July to around now. Dr. Daniel Griffin is MD, PhD, chief of infectious disease at ProHealth, researcher at Columbia, president of the group Parasites Without Borders, and a regular on the podcast This Week in Virology. Our lines are full with people calling in with questions. You can also text us at the same number 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

Here's a question coming in via text. Dr. Griffin, a listener asks, "Is masking back in New York City healthcare facilities?" I think they mean as a requirement because the listener writes, "My mom caught COVID rehabbing from another life-threatening experience in a nursing home this past summer due to no masking by healthcare workers." At least that's why this listener thinks it happened. I know other people have been surprised recently by going to doctor's appointments and into healthcare facilities and they're masked. The healthcare workers aren't masked. They ask about it and the worker says, "No, we don't have to do that anymore."

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Thank you for texting in this question. It's a bit of a patchwork across different facilities. People may know, sometimes I'm seeing patients out of Long Island. Sometimes I'm attending the Dr. House at Columbia at New York Presbyterian in the city. I had the chance to be with the new interns. With the new interns, we were still at Columbia Presbyterian, we're still in masking in all clinical situations. Some of the hospitals on Long Island had done away with mask mandates but actually last week, some of the facilities had gone back to mask mandates.

I think the other, and this is important too, if I was in an outpatient office setting, if a patient is more comfortable with a mask there's a lot of reasons to be sensitive to our patient. Nothing troubles me more than when a patient requests that the healthcare provider wear a mask and the healthcare provider responds with, "Oh, we're not required anymore." What happens when they do away with mask mandates for the surgeons? Well, I will still try to find a surgeon that wears a mask during my surgery.

Brian Lehrer: Listener asks, could you please clarify the distinction between having the disease COVID and just testing positive with no symptoms in terms of transmissibility?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Thank you for asking that because this is one of the big things about this virus, SARS‑CoV‑2 that that really created a problem, a challenge, well, I can say a bit of a disaster for us is that a lot of viruses, a person has symptoms, they're coughing, they're sneezing, that's when they're contagious. That was the case with SARS 1, SARS-CoV-1, back years ago is people were not transmitting until they were sick. What we have seen with SARS‑CoV‑2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is a lot of individuals never get symptoms. A lot of individuals prior to getting symptoms are able to transmit that virus to others. There is both an asymptomatic and a presymptomatic transmission that occurs with this virus.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call. Here's Jeff in Albany. You're on WNYC with Dr. Daniel Griffin. Hi, Jeff.

Jeff: Hi, Dr. Griffin. Thanks so much for being on this morning. A couple of quick questions. When New York City rolled out those numbers on hospitalizations, are those hospitalizations due to COVID or are those just people that were hospitalized and they found they had COVID?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Brian, since you put up the numbers, you should tell us. That is actually, and I think you make a good point, that is often a challenge. Clearly, the data we get when we get on deaths, their deaths due to COVID-19. Sometimes when you look at the trend in hospital admissions, that can get a little bit less refine, less subtle, less hard to pin down.

Brian Lehrer: I didn't see in that data graphic that I was referring to before, whether the New York City Health Department released that particular distinction. What I saw was the number of hospitalizations of people that's the with COVID number is three times what it was in early July. That certainly indicates that more people are getting COVID, whether some of them are asymptomatic or not and are surprised that they have COVID when they get their routine screening when they enter the hospital. You also mentioned that deaths are going up, which is the unreputable number in terms of the meaning of the transmission of the new variant, right?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes. Not only that, and Jeffrey, I think it's glad I'm really positive you're asking this because the deaths, if anything, we're really careful not to call something a COVID death if they died from something else, and maybe in a sense, I think we may undercount. Someone gets COVID and then three weeks later they have a heart attack and die. There probably was some aspect of the inflammatory hypercoagulable state of COVID that triggered that heart attack, but we do not count that, that counts as a heart attack.

We're probably even undercounting the number of deaths that COVID triggers. Those are hard numbers. When someone ends up getting COVID, dying within the first two weeks, then clearly that's a COVID death.

Brian Lehrer: Another listener writing to me asks about the timing of when to get the COVID vaccine if people have had a recent case. For example, someone emailed saying they got COVID over the 4th of July weekend and this person wonders when she should get the new booster.

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Excellent question. Now that everyone has had either three shots or three shots one of them being an exposure to COVID, we're really looking at boosting. The boosting is a three to four-month boost. Getting that infection probably does give a three to four-month boost. Most of us would recommend, based on the science, that if you had an infection, wait three months before you get that booster.

Brian Lehrer: Kate in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Kate.

Kate: Oh, hi. Thank you to taking my call. I was asking, I think what you were just talking about, two things. First of all, I'm back at work because I tested negative, and now the phone's ringing.

Brian Lehrer: Do you need to get it?

Kate: I tested negative on Friday. No, this is way more important. Thanks, Brian. Talking to you is the most important thing I could do today. I had a really nasty bout of COVID. I tested negative Friday so I am back at work, but I still feel really rough, really bad. When can I get the booster because I don't want to go through this again. Also, I was really surprised having been vaxxed and boosted how utterly unwell I have been this past week. Sweating, severe muscle pain, feeling like somebody is crushing my chest and poking me in the throat, dizzy spells, lightheadedness, all sorts of things like that. Is that what we are seeing with these new variants? Worst symptoms?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes. Kate, thank you for calling in. One of the challenges with COVID that I think a lot of people struggle with is that people have had different experiences. Maybe for some people, it was a sore throat, and then the same person gets COVID again a number of months later, and this time they are laying out. They are in bed. They're doing nothing that, as you're describing, really horrible experience. Every time there's a new variant, there's always a news piece on the new variant presents this way versus that way. Now we're seeing diarrhea, now we're seeing sore throat.

COVID is a viral disease and viruses present like viral diseases. Some people have diarrhea, some people sore throat, some people a lot of trouble breathing and chest discomfort. Some people that horrible myalgia. The big thing is that people can respond differently. I'm not sure that the variant really changes the presentation. Whenever we look back in time, once we've had enough time and experience with the new variant, we keep learning this lesson over and over again. This is a viral illness. It presents like a viral illness and the only way to know whether it's COVID or not is to do that test.

Kate: I think I'm just scared. I don't want to be scared anymore. I think like everybody listening right now we're so fed up with this and it feels like it's never going to end. I feel like I'm never going to get past these symptoms. Even though I'm vaxxed, I'm boosted, I'm masked, I feel like I'm doing the right thing.

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes. Let me continue to respond to that, Kate. I think there's a couple of things here. One other one is when do you get your next booster and so you just right now. There's going to be about three months while your immune system is actually educating itself from this experience. About three months from now. We're early September, so September, October, November, it'll be early December would be the recommendation on the booster. Remember that booster is going to boost. It's going to reduce your risk of even getting infected for a period of time but unfortunately, COVID is here.

There's lots of COVID, so boy, instead of 15 minutes and you get COVID, if you spend an hour, 30 minutes, then you might end up. Unfortunately, COVID is still on the horizon. In addition to the vaccines and something maybe we haven't messaged enough about, getting early treatment. Getting treatment within the first five days can really-- about 90% reduction on top of the vaccines in reducing your risk of a bad outcome and a growing experience that people may feel better a little bit sooner with the treatment.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a text that we're getting a few versions of listener rights. "I have an infant daughter who is now eligible for the COVID vaccine, but I'm unsure whether I should give her the bivalent and outdated shots available now or wait to see if she's eligible for the new vaccine. I haven't been able to find any clear guidance on this." Any that you can give?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes. Thank you for the question. Now that we're maybe 10 days away or less from the release of the updated vaccines, you're close enough now that I would say just wait about two weeks, schedule a time with your pediatrician to talk to them and it probably makes sense for you to just go ahead with the updated vaccines. One of the challenges I say to one of my colleagues, Dr. Berger, is. "Boy, being a pediatrician and navigating all the rapid changes in the pediatric COVID vaccine area has been an incredible challenge. I'm glad that I did decide not to go into pediatrics."

Brian Lehrer: You mentioned the antiviral treatment that people can get and Larry in Brooklyn Heights is calling with a question about that. Hi, Larry. You're on WNYC.

Larry: Hey, hi. Your guest just mentioned this, that you should get treatment within the first five days. This was my experience having COVID and have some acquaintances of mine. You can't get it. You call your private doctor, anybody and they say, "You have COVID? Don't come to my office. If you're really sick, go to the ER." You can't get it. I did read articles in The Times somewhere else saying the actual use of Paxlovid, I believe that's the name of the drug, is much lower than it should be. I'm guessing that's the reason.

If there's a public health way to get this or something, that would be fantastic, but more or less, that's a very hard treatment to get because doctors don't want you in their offices if you have COVID. That's what I have to say.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Larry.

Larry: It's funny. It comes right after Kate who Dr. Griffin just mentioned that get it and her symptoms were the same as mine.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I know somebody in my personal life who says her dad has COVID right now and is having the same problem with access. Dr. Griffin?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Larry, thank you. Maybe this is a plug for Optum. It is an educational.

Brian Lehrer: Your employer?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Yes, Optum, our group. The reason I say it's a plug for that is that all through the pandemic, not only do I do this weekend virology, the clinical updates for our entire group and anyone else who wants to listen, but on a regular basis every Wednesday, I meet with all of our urgent care providers throughout New Jersey, Westchester, Connecticut, New York City, Long Island, just reinforcing that we don't need to have 500 people dying a week. It could be as low as 50. We don't need to have all these people end up in the hospitals.

I had a patient last week that I was speaking to in the ER and she had called one of her providers, not an Optum provider. During the first week actually, she had her daughter do it and the doctor just said, "Well, hopefully you will be okay," and now I'm seeing her in the hospital. This is an ongoing educational issue. Maybe now if you are listening and you don't have COVID, have that conversation with your provider, "Hey, if I get COVID, if I am high risk over the age of 50 or have medical issues, if I get sick will you make it possible for me to get treated in that first five days and reduce my risk of progression by 90%? If the answer is not yes, you need to look for another provider.

We have made it our policy, I'll say it, my personal mission, to make sure that if a individual goes to one of our urgent cares and tests positive, we are willing to spend the time to work through any drug interactions, to look at kidney function. If you are reaching out to your Optum primary care, we are setting up telehealth within the same day, within 24 hours to work through because we do not want our patients unnecessarily progressing when we have these just tremendous tools out there.

Larry, no, I appreciate putting this out here. I shared on this weekend virology where places down in Florida because of misinformation not utilizing this as much as they should and I am troubled to hear that here in the northeast where we're supposed to be the pinnacle of medical excellence, we are having patients who should be appropriately treated falling through the cracks.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, I think I owe you an apology because I was using the old name for your medical group. You've been saying Optum, but I introduced you as with ProHealth. It's now Optum, just to be clear, for Dr. Daniel Griffin's association. There's another treatment that a listener just wrote to ask me about called Metformin, not as well known to the general public as Paxlovid. Is that something you recommend for COVID?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Let me talk about that. That is a great question. Thanks for bringing it up. Actually, United Health Group was involved, and some of my colleagues were involved in the trial looking at that. As far as treatments during the first five to seven days that prevent progression to hospitalization and death, number one, Paxlovid. Number two, if you can get it, a three-day IV remdesivir. The next option would be molnupiravir, Thor's hammer. Some people are asking during this first week, "Is there something I can do to potentially reduce my risk of developing long COVID?"

We get some preliminary data that maybe some of these antivirals like Paxlovid may reduce that chance by 20%, 30% which a lot of people are more worried about long COVID than these acute hospitalizations or even death. Living with long COVID can be a horrible thing. There was a trial, the COVID out trial. I think David Boulware was the first author. My friend Ken Cohen was on this. If you do a rather challenging regimen in that study, there may be a reduction in getting long COVID down the line. We're not sure that that reduction is better than Paxlovid, so most of us are still recommending if you can access Paxlovid, that's probably your best choice for preventing that long-term outcome.

Brian Lehrer: We're over time, but I'm going to throw in one final note from somebody who just sent an article saying to the listeners concerned about accessing Paxlovid that you can get a Paxlovid prescription from a New York state-licensed pharmacist bypassing the doctor. It doesn't reference other states, but at least in New York. Do you know that to be the case?

Dr. Daniel Griffin: That is the case. A number of our pharmacies have stepped up and they have protocols where you can go in, you can get that test, you can get that prescription, and you can get treatment. We do have options. If you're potentially a candidate, if your risk of progression is not zero, and you would like to reduce that by 90%, so what are those things? You're over the age of 50, you have medical problems and actually being obese is even one of those, hypertension, et cetera. If your doctor won't do it, and you're not able to navigate that way, some of our pharmacies have these programs. Jump on your computer, Google away, and let's make that happen.

Brian Lehrer: Dr. Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, chief of infectious disease at Optum, researcher at Columbia, president of the group Parasites Without Borders, and a contributor to This Week in Virology, the podcast. Thank you so much for being a contributor here as you come on pretty frequently with us. Dr. Griffin, we always appreciate it very much.

Dr. Daniel Griffin: Oh, Brian, thank you for having me, and everyone, thanks for listening. Be safe out there.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.