Ask a Meteorologist: New York Metro Weather

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

[music]

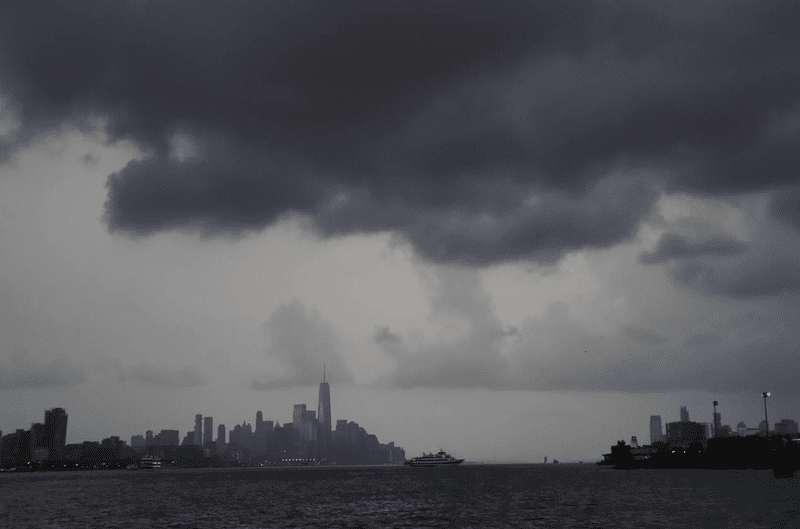

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. When the weather forecast for the New York Metro area on Monday included a severe thunderstorm warning, wind gust of up to 60 miles per hour, large hail, and even an isolated tornado possible, Northern New Jersey and the Lower Hudson Valley too, you might have been worried we'd get the sort of conditions that have so overwhelmed this area from time to time in recent years. There was a collective sigh of relief when a good chunk of the region was spared.

We figured this might be a good chance to demystify the science of weather forecasting a bit as we've done on the show a couple of times before, and it's also a good time to check in on how well the city at least is communicating about extreme weather. Rewinding back in September, Hurricane Ida you'll remember made clear the need for better messaging around severe weather conditions when many in New York City suddenly met quickly rising flood waters. Those emergency declarations should have arrived far sooner in that case. There's a really short piece on the website Curbed that we'll link to where you can read about that in greater detail.

Right now let's hear from John Homenuk, meteorologist and founder of New York Metro Weather. If that name sounds familiar, it's probably because you've seen New York Metro Weather's incredible Twitter feed. Every day it provides a rating out of 10 of the day's weather along with a vibe. Wednesday's weather rating today is 9 out of 10, still a bit of a breeze as it describes it, but the sun is shining and the temperature is heading into the lower 70s this afternoon. ''The vibes remain pretty dang good.'' Hey, John, welcome back to WNYC. It's good to have you on this 9 out of 10 day.

John Homenuk: Oh, Brian. Thanks for having me. I really appreciate it.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, this is a quick 10-minute segment, but what if you always wanted to ask a meteorologist. How can John Homenuk one of the founders of New York Metro Weather help you understand how his team or anyone else predicts the weather, your chance to ask a meteorologist at 212-433-WNYC. If you get in quickly, 212-433-9692 or tweet @BrianLehrer. What happened on Monday?

John Homenuk: Monday was a classic day where I think the focus on communication and improving how we get the point across when it comes to the weather is going to be important moving forward. The risk obviously existed for severe thunderstorms throughout the day, but as I'm sure you know, severe thunderstorms are often quite localized. They are sometimes a mile or two across, maybe a little more than that, depending on the size of the storm itself. Here in New York, we often get lines of storms.

They come through from west to east, but in this case, this was just a couple of individual cells that were moving through from west to east. Some areas got heavy rain, some areas got winds. There was damage in parts of Upstate New York and Eastern Pennsylvania but other areas such as a large majority of the New York City Metro were able to avoid the severe thunderstorms themselves. There was one

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

storm that moved I think it was in Queens and then out into Nassau County.

Other than that, we were able to avoid it and that's just the nature of severe thunderstorms. Thunderstorm forecasting is one of the most complex things there is to do in meteorology. There is a major focus in the meteorology industry as a whole in pinning down those warnings and being better at communicating them to the public.

Brian Lehrer: One thing I see about New York Metro Weather is that you rarely, if ever, at least of late, say that there's a 30% chance of rain, put it in those rounded percentage terms. Instead, you'll say there's possible rain all day or all afternoon. Is that a deliberate choice to avoid the percentages?

John Homenuk: It is. I think we found that when it comes to communicating the weather, people want something that's digestible. I think if you say 30% here and 50% there, it just creates more confusion. I think for someone that's heading out for their commute to work every day, what they want to be able to read is, ''Okay, there's a chance of showers this afternoon.'' We don't know that there's going to be showers everywhere, but there is a chance that there's going to be a shower. We don't expect any severe weather or hazardous weather, but it might rain, and so people can prepare accordingly. I think the percentages start to get a little confusing. Until we can pin down how we can best use the numbers, sometimes it's just a little better to be a little bit more direct.

Brian Lehrer: Isn't it better to know that there's a 30% chance of rain or a 70% chance of rain than to just say there's a chance of rain all day?

John Homenuk: Well, I think it comes down to the descriptions of it. I don't think that we just say there's a chance of rain all day. I think we get a little bit more specific than that. The percentages get confusing and it's funny, we have a couple of emails about this just from a couple of weeks ago. The question is, does it mean 30% chance of rain where I am or does it mean 30% chance of rain for this hour in this location? It's just confusing and people don't understand. We have different terms we'll use-- there's been a lot of studies done in terms of different words to use for severity. Slight, moderate, enhanced, high. How do people receive those words? We've been using more words in grammar to get the point across as opposed to percentages.

Brian Lehrer: Adjectives instead of numbers.

John Homenuk: Absolutely.

Brian Lehrer: The hook for this segment is the severe weather warnings many in the region got on Monday. Then, for the most part, it never happened and I'm curious what pitfalls you think cities and other localities should avoid when they're sending out communications about severe weather because it's important that people trust those communications when they do come, right?

John Homenuk: Absolutely and here's one of the major things. Right now when severe thunderstorm warnings are issued, the folks at the National Weather Service,

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

they do an amazing job of getting these warnings out to people, especially tornado warnings when you get the notification on your phone. The nature of these storms as I mentioned earlier is a lot of them are so small and they move erratically and they're hit or miss. Even our best weather models, they have a difficult time modeling where these storms are going to go. One of the major focuses, how can we narrow down the warning areas?

If you get a tornado warning right now, sometimes that warning includes areas that are at a pretty wide region that are probably not going to be impacted by the tornado. The tornado itself might be a quarter mile wide, maybe even less than that. How do we get better at narrowing down the area that we push that warning out to? That's a major focus of communication and meteorology moving forward. From our perspective as a public entity that communicates to weather, we have the ability to say that.

The warning gets issued and we are on Twitter or live streaming and we can say here's where the warning is, but these are the towns that are at actual risk and we can point to it on a map. I think it's those secondary sources that we can use to make the weather a little bit more digestible for people that are becoming really important moving forward.

Brian Lehrer: Question for you from Twitter listener asks, ''Why is it called meteorology, not weatherology?''

John Homenuk: [laughs] That's a great question.

Brian Lehrer: It doesn't have anything to do with meteors, does it?

John Homenuk: Well, yes. I don't even really have the answer to it, it's funny. One of the jokes, when I was in college, is someone came up to me. I was at a coffee shop and I said, ''Oh, I'm a meteorologist,'' and the response was, ''Oh, so you're the guy I'll turn to whenever I want to know when the next meteor shower is?'' I just laughed because there's not really much you could say, but meteorology is the study of the atmosphere and the weather and meteorology as it relates.

Brian Lehrer: Martha in Ridgewood, you're on WNYC. Hi, Martha.

Martha: Hi, my question has to do with Doppler radar online. I'm just wondering how accurate it is when planning your day and seeing where and when rain is going to hit and I'll take my response off air.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for asking a meteorologist.

John Homenuk: Hi, Martha, thank you for the question. Doppler radar is extremely accurate, especially if you're using the one available on the National Weather Service website. The one thing is obviously you're not going to see into the future, so you're just seeing what's up until now. You can loop that and make your own conclusions from there, but it's quite accurate in the National Weather Service page hosts a Doppler radar that updates every couple of minutes, so you can look at your

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

location on a map and see where the showers and storms are.

Brian Lehrer: Louis in Brooklyn you're on WNYC to ask a meteorologist. Hi, Louis.

Louis: Hi, Brian. I've always wondered that sometimes when you want to plan a trip in advance, you can go into the weather channel and see the forecast for 30 days in advance. I'm wondering how is it that you guys can see so far in advance, like a month in advance. They'll say that it's going to be cloudy or sunny. How do you guys do it?

John Homenuk: I'm going to provide a very disappointing answer to this. The data that you're getting there is just an algorithm typically from a couple of weather models and usually, it's very inaccurate. We do quite a bit of seasonal and long-range forecasting on a consulting basis as well, and I can tell you personally, that it is almost impossible to predict the exact weather 30 or 40 days in advance at any given location.

While you might get a general idea as to what the average temperature is and what maybe the cloud cover might be on average, it's really just a shot in the dark when it comes to the actual observed weather conditions. There are 30 or 40 different weather models that we use on a daily basis and those long-range forecasts can vary so dramatically depending on which model you use. I would say take it with a very serious grain of salt.

Brian Lehrer: Lisa in Brooklyn wants to ask a meteorologist what 30% chance of rain really means, right, Lisa? Oh, Lisa went away. All right. I used to make a joke that why would they ever say 50% chance of rain? Why don't they just say, we don't know? Ha ha ha, but really it's that the history tells us that half the time under those conditions, it will rain half the time it won't, right?

John Homenuk: That's exactly right. You mentioned we don't know. That's a really big focus. For us, it's okay to say that we don't know for sure. When it comes to communicating the weather people, and I would say, especially in New York, they just want to know what the deal is. If we are going to sit there and try to pretend like we know for sure, that's even worse. What we take pride in is we go and say, ''Hey, listen, we're not 100% certain, but these are the possibilities.''

Brian Lehrer: Last question. Your forecast for today, your description for today, I should say, still a bit of a breeze, but the sun is shining and the temperature is heading into the lower 70s this afternoon. The vibes remain pretty dang good. You rated a 9 out of 10. What would a 10 be?

John Homenuk: I always envision a 10 as being a day when you walk outside and you don't have to worry about the weather at all, you don't even need to bring a life jacket. We're talking probably mid to upper 70s, a very light breeze, low humidity, and no chance of range. Today was pretty close.

Brian Lehrer: John Homenuk, meteorologist and co-founder of New York Metro Weather, which you should absolutely find on Twitter. Have a 9 out of 10 day, John. Thanks.

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

File name: bl051822dpod.mp3

John Homenuk: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.