30 Issues: Who is the Real Law and Order Candidate

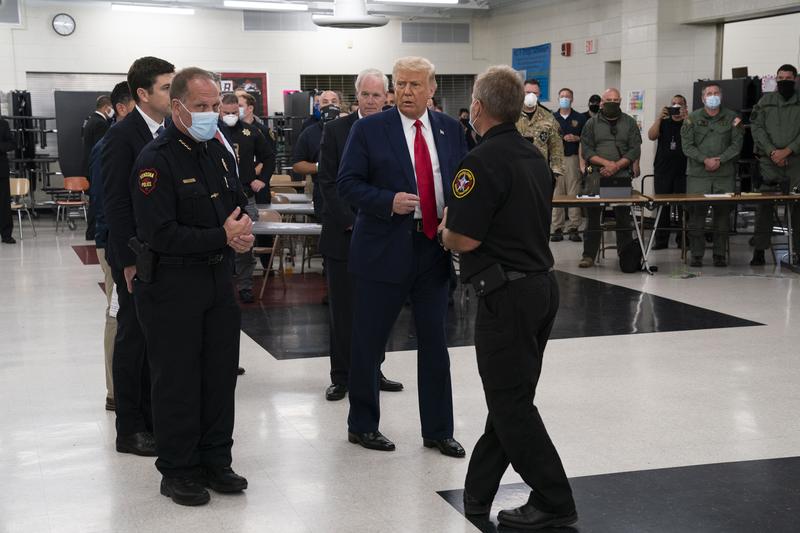

( Evan Vucci / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now we continue our election series, 30 Issues in 30 Days. We're in a run of eight days in a row on racial justice issues facing Trump and Biden.

Today what do people mean when they say law and order and who's the real law and order candidate? Let's do some history first. In 1968, there were two people running for president who called themselves the law and order candidate, George Wallace, who as governor of Alabama in 1963, proclaimed, "Segregation now segregation forever."

He ran as a third-party candidate in '68, that was the year that Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, and there were protests sometimes violent in the streets since it was becoming unacceptable to just say "segregation forever" by then. Wallace avoided the topics of racial justice and police brutality, law and order became Wallace's code.

George Wallace: If you walk out of this building today and get knocked in the head, the person who knocks you in the head is out of jail before you get in the hospital, and on Monday, they'll try the policeman about it, he'll wind up getting in trouble about it.

Brian: Sound familiar? George Wallace actually won the electoral votes of five southern states in 1968 and despite that, Richard Nixon, the other law and order candidate, was able to win the presidency running on a similar if more somberly delivered theme, but in just as much denial about racial injustice in his public emphasis.

Richard Nixon: When the nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is plagued by unprecedented lawlessness, when a nation has been known for a century for equality of opportunity is torn by unprecedented racial violence, and when the President of the United States cannot travel abroad, or to any major city at home without fear of a hostile demonstration, then it's time for new leadership for the United States of America.

[appluase]

Brian: Richard Nixon in 1968. Fast forward 20 years, now, for all we like to look at George HW Bush as a friendly moderate these days. He got elected in no small part by denouncing Democrat Michael Dukakis in 1988 as soft on crime and ran the infamous Willie Horton ad. Here's the audio that ran with two successive images of Willie Horton's face, designed, as Bush's campaign manager later admitted, to stoke and capitalize on white fear of Black America.

Advert: Bush and Dukakis on crime, Bush supports the death penalty for first degree murderers. Dukakis not only opposes the death penalty, he allowed first-degree murderers to have weekend passes from prison. One was Willie Horton who murdered a boy in a robbery, stabbing him 19 times. Despite a life sentence, Horton received 10 weekend passes from prison. Horton fled, kidnapped a young couple stabbing the man, and repeatedly raping his girlfriend. Weekend prison passes, Dukakis on crime.

Brian: This dynamic between Democratic and Republican presidential candidates is nothing new. Another parallel between Bush and Trump is that when Thurgood Marshall retired from the Supreme Court, George HW Bush replaced him with Clarence Thomas, the most conservative Supreme Court ready nominee he could find to replace the progressive Marshall without making the court all white again.

Now we have Trump trying to keep a woman in Ruth Bader Ginsburg's seat, but one with opposite judicial sensibilities. Clarence Thomas, being the most conservative justice on the court to this day by most accounts, and the Willie Horton ads place in history are two of the elder Bush's most enduring race and justice legacies.

Trump, while aberrant in many ways, follows in a conservative and Republican tradition on this, as here we are in another summer of both violence and racial justice. The Democrat's weakness on the issue as crime was on the rise through the Reagan and Bush '80s and after that '88 election, that all helped lead to the so-called New Democrat positions of candidate Bill Clinton for his successful campaign in 1992.

In '94, they passed that crime bill that is now blamed in part for the mass incarceration of mostly Black men. Joe Biden was a senate leader on that bill in '94 and in his televised Town Hall last night, he expressed regrets when he was asked by one of the questioners in the audience.

Politarhos: Thank you, Vice President Biden. Nice to meet you. What's your view on the crime bill that you wrote in 1994 which showed prejudice against minorities? Where do you stand today on that?

Joe Biden: Well, first of all, things have changed drastically. That crime bill, when it voted, the Black Caucus voted for it, every Black mayor supported it across the board. The crime bill itself did not have mandatory sentences except for two things. It had three strikes and you're out which I voted against in the crime bill, but it had a lot of other things in it that turned out to be both bad and good.

I wrote the Violence Against Women Act, that was part of it. The Assault Weapons Ban and other things that were good. What I was against was giving states more money for prison systems that they could build, state prison systems. You have 93 out of every 100 people in jail now is in a state prison not in a federal prison because they built more prisons.

I also wrote into that bill a thing called drug courts. I don't believe anybody should be going to jail for drug use, they should be going into mandatory rehabilitation. We should be building rehab centers to have these people housed. We should decriminalize marijuana, wipe out the record so you can actually say in honesty have you ever arrested for anything, you can say no, because we're going to pass a law saying there is no background that you have to reveal relative to the use of marijuana.

So there's a lot of things, but in addition to that, we've got to change the system. I joined with a group of people in the house to provide for changing the system from punishment to rehabilitation along with a guy named Arlen Specter, who you may remember. I wrote the Second Chance Act.

Stephanopoulos: In the meantime, an awful lot of people were jailed for minor drug crimes after the crime bill.

Joe: exactly right.

Stephanopoulos: Was it a mistake to support it?

Joe: Yes, it was but here's where the mistake came, the mistake came in terms of what the states did locally.

Brian: What the states did locally, not what we did in Washington. We'll fact check that coming up. There are various kinds of violent crime, of course. Street crime is one, it is going up this year around the country it can't be denied. Domestic terrorism is another. There are mass shootings too. Democrats see Republicans as soft on crime when they support no or few limits on gun possession.

Amy Coney Barrett is known in part for defending certain felons continued federal right to bear arms, but not so much their voting rights when various states or cities want to restrict them. Trump is known in part for sending in federal law enforcement to Portland, but winking at white supremacists who show up armed to pro-police or pro-Trump protests.

Last night in his NBC town hall, Trump denounced white supremacy only defensively when pressed, and it felt that he had to equate it when asked by Savannah Guthrie, the moderator, with political violence from the left.

Savannah Guthrie: You were asked point-blank to denounce white supremacy. In the moment, you didn’t. You asked some follow up questions. "Who, specifically?" A couple of days later, on a different show, you denounced white supremacy.

Donald Trump: Oh, you always do this.

Savannah: My question to you is-

Donald: You always do this. You've done this to me, and everybody--

`

Savannah: -why does it seem like--

Donald: I denounce white supremacy, okay?

Savannah: You did, two days later.

Donald: I've denounced white supremacy for years, but you always do it. You always start off with the question. You didn't ask Joe Biden whether or not he denounces Antifa. I watched him on the same basic show with Lester Holt, and he was asking questions like Biden was a child.

Savannah: Well, so this is a little bit of a dodge.

Donald: Are you listening? I denounce white supremacy. What's your next question?

Savannah: It feels sometimes your hesitant to do so like you wait a bit.

Donald: Hesitant? Here we go again. Every time-- In fact, my people came, "I'm sure they’ll ask you the white supremacy question." I denounce white supremacy, and frankly, you want to know something? I denounce Antifa, and I denounce these people on the left that are burning down our cities, that are run by Democrats--

Brian: The equivalency is false according to Trump's own FBI Director, Christopher Wray, and what he testified to recently before Congress.

Christopher Wray: Within the domestic terrorism bucket category as a whole, racially motivated violent extremism is I think, the biggest bucket within that larger group and within the racially motivated violent extremists bucket, people ascribing to some kind of white supremacist type ideology is certainly the biggest chunk of that.

Brian: FBI Director Chris Wray. Trump last night also feigned ignorance of the QAnon conspiracy movement, which explicitly supports him, and which the FBI also considers a domestic terror threat.

Donald: Don't know what they're doing.

Savannah: While we're denouncing, let me ask you about QAnon, it is this theory that Democrats are a satanic pedophile ring and that you are the savior of that. Now can you just once and for all, state that that is completely not true and disavow QAnon in its entirety?

President Trump: I know nothing about QAnon.

Savannah: I just told you.

President Trump: You told me, but what you tell me doesn't necessarily make it fact, I hate to say that. I know nothing about it. I do know they are very much against pedophilia. They fight it very hard, but I know nothing about it. If you'd like me to-

Savannah: They believe it is a Satanic cult run by the deep state.

President Trump: -study the subject. I'll tell you what I do know about. I know about Antifa and I know about the radical left and I know how violent they are and how vicious they are and I know how they're burning down cities run by Democrats, not run by Republicans.

Brian: Who's the real law and order candidate? Well, this all came to a bit of a head for about a minute at the actual Trump and Biden debate last month.

President Trump: During the Obama-Biden administration, there was tremendous division. There was hatred. You look at Ferguson, you look at-- you go to very-- many places. Look at Oakland, look what happened in Oakland, look what happened in Baltimore, look what happened-- frankly, it was more violent than what I'm even seeing now but the reason is that the Democrats that run these cities don't want to talk like you about law and order and you still haven't mentioned. Are in favor of law and order?

Biden: I'm in favor of law and order. [crosstalk]

President Trump: Are you in favor of law and order?

Biden: Go ahead and say it.

Chris Wallace: You ask a question, let him finish. [crosstalk] Let him--

Biden: Law and order with justice, where people get treated fairly. The fact of the matter is violent crime went down 15% in our administration.

Brian: With Chris Wallace trying to keep a little debate law and order there. What do people mean when they say law and order and who's the real law and order candidate? With me are two guests Inimai Chettiar, the Federal Legislative and Policy Director for the Justice Action Network. She spearheads federal legislative priorities and policies in Washington. A key focus as the bipartisan organization gears up for a major push to build on the progress of the First Step Act in Washington.

Prior to joining the coalition, Inimai directed the justice program at the Brennan Center for Justice at the NYU School of Law, where she established the center as a national force to end mass incarceration.

Also with us is Jeffrey Butts, Director of the Research and Evaluation Center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His work focuses on discovering and improving the effectiveness of policies and programs related to the justice system. He is the author of books, including Waiting for Justice, Moving Young Offenders Through the Juvenile Court Process. Jeffrey and Inimai, thanks for coming on. Welcome back both of you to WNYC.

Jeffrey: Good morning.

Inimai: Good morning, thank you so much for having us.

Brian: As that brief history that we ran through my show, different people mean different things when they say law and order. Inimai, how do you see that range?

Inimai: I think that the rhetoric here is really quite interesting. I'm not sure that there is a clear answer to who's the "law and order candidate". One thing that we are seeing is, while you do have President Trump using the law and order rhetoric from these past presidential campaigns, you also have the president actually campaigning on criminal justice reform and using that as a talking point. Saying that he's done more than any other president for criminal justice reform and then specifically attacking Biden.

I thought it was really interesting in the last debate where Trump went after Biden for the '94 crime bill and then pointed out that Biden tried to lock up more people while Trump "tried to send people out of jail." I just thought that is a new and really interesting twist on the way that some of this rhetoric is playing out. That while there is this law and order and policing going on in the background, you also have this issue of both candidates arguing over who would be best on criminal justice reform.

Brian: Can you each talk, and Inimai, I'll stay with you first about the intersection of the phrase law and order for actually meaning reductions in violent crime and at the same time as code for stoking white racial fear or a backlash against criminal justice reform.

Inimai: I think that the use of the term law and order as you've laid out in terms of the history of it is very much premised on creating fear of crime and racial tensions. I think that that's absolutely right in terms of that's being used as code for that.

What complicates things a little bit more in this election, I think, is that we do have a little bit of an up and down in crime right now and so I think that using the law and order rhetoric is actually making people a little bit more afraid than they would otherwise normally be.

It's just complicated by this whole factor of President Trump talking specifically about being able to undertake criminal justice reforms. I think one thing to point out is, Trump did pass the First Step Act and that is seen as something that supports criminal justice reforms, obviously, but obviously that brings down crime as well. Letting more people out of prison and sending them to proven alternatives to prison, that actually helps bring down crime and bring down recidivism rates. Again, it's a little bit of a confusing message that is coming out of the White House.

Brian: Jeffrey Butts, thanks for joining us. Same question.

Jeffrey: I think we all know that Trump lies chronically and he's not the only politician that does that, but he does it so badly that we can see it and in the crime and justice field, I thought your summary, in the beginning, Brian, was excellent and it's interesting that you started off in 1968 because that's the first presidential election where I was old enough to have rational thought.

I remember George Wallace and the reaction and then it's so spooky to see these same themes come back again and again, and it's often the conservative politicians that use this phrase law and order, and they don't mean public safety, public well-being, health, and community safety. They mean boots and batons and threats and prisons and it is explicitly meant to not only stoke fears, but reward the fears of the predominantly white community about racial and ethnic minorities and it's always been that.

The one thing I agree with that Trump said to Savannah Guthrie during the debate, I do agree with his statement where he said, "Just because you tell me something doesn't mean it's a fact." That is certainly true in politics these days.

Brian: For you who has studied juvenile justice as much as you have, was Biden accurate when he said it wasn't the 1994 federal crime bill that led to so much mass incarceration, it was what the states were doing at the same time?

Jeffrey: Yes, and not only that, it's predominantly state. The federal lockup system represents maybe one-tenth of the justice system. It's mostly a state and local system, but the increase in incarceration that we saw really kicked off in the late '70s, about 1980 it started to climb, and it had been stable for a long time. Since the 1920s, prison populations accounted for about 100 out of every 100,000 US population.

After 1980, it increased, it quintupled and that had reached a peak before or was near a peak before the 1994 crime bill was actually passed. Then it started to come down a little bit, but I don't think you see criminologists or people that study this field claiming that the crime bill brought down the incarceration rate, because they're fairly independent.

Incarceration response to policy issues and of course somewhat to crime, but it's largely a decision that policymakers choose in terms of how to respond to crime concerns. After quintupling the prison population, I think everyone started to believe that it was not only hugely expensive, but not ineffective and wasn't a good way to accomplish the goal if the goal is public safety.

On the other hand, if the goal is to terrorize communities and thump the chest of the government, by saying, "Look what we can do, we're in charge," then incarceration is very successful, but if you ask people to vote, I don't think they would just vote on a prison as a communication device. They want public safety.

Brian: Inimai, crime did go down as mass incarceration was going up. How do you think history should really reflect that association?

Inimai: I think that that's a complicated association, because as mass incarceration went up, crime went down. That is, however, it's not causal. There have been a ton of studies, including some that we've done that show that it was not mass incarceration that brought down crime, but rather it was socio-economic factors such as jobs and poverty and other economic indicators that improved that actually brought down crime.

I think it's easy on first glance for people to associate the two, but in fact, they're actually not associated. Just for a minute on the '94 crime bill, I think there's a little bit of a conflation in this discussion around a cause versus a contributor to mass incarceration. I think that everyone can agree that the '94 crime bill contributed to mass incarceration, even if it was not. There's obviously no one cause to mass incarceration.

Obviously, the states were passing their laws, the local governments were doing what they were doing, but it still remains that the '94 crime bill was the biggest and most public tough-on-crime law. I think that that rhetoric, and those policies, obviously, were contributors to people being in prison.

Brian: Today, we have several things going on at once, a racial justice movement that very much included a focus on police violence after the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Jacob Blake and Daniel Prude and others. We have some instances of violence related to the protests, and we have a rise in street crime.

We have a white supremacist and other right-wing terrorism wave on the rise, as with the foiled plot to kidnap the governor of Michigan, and apparently of Virginia too and other things that we've seen on the streets of cities. How do you even describe the violent crime threat of today? Jeffrey, I'll start with you, and what does a holistic response to it look like?

Jeffrey: Well, a holistic response realizes that crime, of course, is a huge label, it means a lot of different things, but most people think of violence. In the public when you say crime they think of violence. Violence has gone up since the pandemic, but mostly just gun violence and crime, in general, is not significantly up, so there are fluctuations from city to city.

Interpreting that and explaining that of course is very complicated and the one thing I can tell you is if anyone ever says something to you about crime, and you think, "Wow, I didn't know that." They're probably not telling you everything you need to know, because it's complicated.

Let me give you one example, I'll do a Trump trick on you. Did you know in the last year murder jumped by double-digit percentages, in Tulsa, Omaha, and Miami and all of those cities have Republican mayors? That's a factually correct statement, and it's also incredibly misleading, because a lot of cities that experienced increases in crime has nothing to do with the party in power, it's a community function or a community factor. That's what we need to pay attention to, is the well being of communities and how people feel in their neighborhoods. That's how people start to behave badly is because they're stressed out.

Brian: Inimai, same question.

Inimai: I guess what I would say is, in terms of your other question around solutions, and I don't think it's all as depressing as it can seem on first glance. One of the few silver linings is that we do actually have the Republicans and Democrats agreeing on the need to reform our justice system and on the need for policing reform, even if both parties-- Obviously, the Republicans don't want to go as far as the Democrats do, but I do think that there is consensus to make change and to see that the system is broken in terms of how we are addressing crime and justice.

Brian: Do you think we can get to a place where everybody understands that, as Reverend Al Sharpton said on the show a few weeks ago, that when you come from the neighborhoods like the one that he grew up in, when you say protect me from crime, it refers to the cops and the robbers as he put it, people are afraid of the cops and the robbers. Inimai.

Inimai: [crosstalk] Go ahead.

Brian: Go ahead Jeffrey, you first.

Jeffrey: I was just going to agree, I think it's disorder that people fear, unpredictability and danger and the danger can come from multiple directions. We in this culture though, we tend to use the term crime and criminals as if it really means something. It's actually about the full spectrum of disorder and things that cause harm. It's really hard to have a political conversation along those lines because there's too much benefit for politicians to, again, stoke the fear that we've been seeing for centuries.

Brian: Inimai, a last word.

Inimai: I think that's absolutely right. There are a lot of communities where people are as afraid of the police, if not more afraid of the police, than of people who are committing other crimes. I think that's absolutely right.

Brian: Inimai Chettiar is the Federal Legislative and Policy Director for the Justice Action Network. Jeffrey Butts is Director of the Research and Evaluation Center with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Thank you both so much for joining us.

Jeffrey: You're welcome.

Inimai: Thank you.

Brian: Our eight consecutive days of looking at racial justice issues facing Trump and Biden continues on Monday with a look at affirmative action at colleges and universities.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.