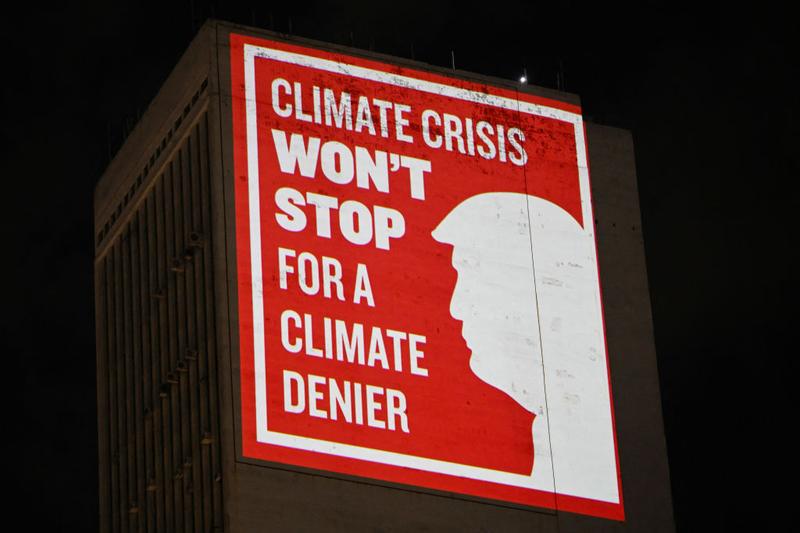

How Trump's Presidency Galvanized a Climate Movement

( LUIS ROBAYO / Getty Images )

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now it being Tuesday, our Climate Story of the Week. Since the election of Donald Trump earlier this month, obviously, many in the scientific community and the front lines of the fight to prevent or mitigate the worst impacts of climate change have been concerned, but a new op-ed in the Miami Herald looks back at the first Trump administration and finds what the writers call a glimmer of hope. They say despite Trump entering the White House in 2017 as a climate skeptic, corporate investment in climate action grew, and that's in large part because of market demand.

Joining us now is one of the co-authors of that op-ed in the Miami Herald. Stephen Hammer is founding CEO of the New York Climate Exchange. He is also just back from the COP 29 climate conference in Azerbaijan. Dr. Hammer, thanks for coming on. Welcome to WNYC today.

Stephen Hammer: Brian, thanks so much. I really appreciate it.

Brian Lehrer: Your op-ed outlines three ways to continue climate action during a second Trump presidency. Before we get into those, can you remind listeners about what happened in the first term that you say actually offers a glimmer of hope for Trump too?

Stephen Hammer: Sure. I think you've got to look at the totality of what the administration tried to do versus where the others took action, whether it was the markets, whether it was statehouses, whether it was municipalities. This is not the president controls everything type situation. Clearly, he withdrew from the Paris Agreement. That had some ripple effects in terms of sending market signals telling the private sector, "Hey, I want you to pay attention to this versus that." In reality, those markets were already moving. They were already seeing those signals.

You can look at the wind sector, which continued to expand at a fairly dramatic rate over the totality of the Trump 1 administration. You saw some impacts in terms of solar, where the level of subsidies may have changed and there was an evening balancing out in terms of how much was actually deployed. That trend towards more and more deployment over time continues unabated.

What I think we're going to be most surprised at is, again, the rallying of interest and attention by people, by policymakers at all different levels who are still committed to these issues, who know that this is where we need to be taking action, and regardless of what the president may or may not believe, they think it's going to be critical that we continue to march forward on this.

Brian Lehrer: He seems to be or he was in the campaign running on an even much more aggressive anti-climate policy platform than he was in 2016. Tell me if you disagree, but I'm going to play a clip of the person he's now nominated as Energy Secretary, fracking executive Chris Wright, with something that he said about what's to come.

Chris Wright: We have seen no increase in the frequency or intensity of hurricanes, tornadoes, droughts, or floods, despite endless fearmongering of the media, politicians, and activists.

Brian Lehrer: Sorry, that's not the clip I thought it was going to be. We're going to find that other Chris Wright clip, but even on that, considering all the intense weather events, extreme weather events that there have been in the last couple of years, and the fact that, as we've talked about in this Climate Story of the Week series, for example, on the recent hurricanes, the oceans are getting warmer year by year over many, many, many, many years, and that produces the conditions for more powerful hurricanes.

There's so much science that says that there have been extreme weather events at the hands of climate change. Do you want to just respond to the clip we did play and take a minute to refute it?

Stephen Hammer: Absolutely. I think that first of, read the headlines. I'm happy to provide some of that information if you're missing out on some of the things that have happened even in the last few months, hurricanes growing in intensity, scientists marking at how rapidly they are increasing in terms of severity, in terms of the wind speed at rates they have never seen before. This is hitting parts of the United States. Take the situation in North Carolina where the level of rainfall came into an area where people thought they were immune from the impacts of hurricanes.

The volume of water that was dropped had a disproportionate impact compared to the level of readiness. No matter what you may think you want to believe in terms of it's not happening, the reality is, and there's plenty of evidence in different parts of the country, you need to begin to pay attention to these issues. I'd also invite them to New York. When was the last time you remember having a brush fire in Prospect Park, in Van Cortlandt Park on the New Jersey, New York border?

These are things that are recognition that we are in drought conditions, that it doesn't take much to actually start these fires. We need to begin to anticipate that this is something that's going to be a more prominent and steady part of our life going forward.

Brian Lehrer: Since you brought up the drought, and this happened in my neighborhood too in Upper Manhattan, I never experienced a brush fire in Manhattan before, but we had a smoke condition in my neighborhood because of multiple fires in Inwood Hill Park last week. The question on many people's minds I think is, wait, when it rained really hard, we said climate change was responsible for heavier downpours and more rains under certain circumstances and stretches of rain than we've had in the past. Now when it doesn't rain, we pin that on climate change too. Does that make sense?

Stephen Hammer: Well, it does because, just focus on the word change, change from a traditional pattern that you have seen over an extended period of decades. Now we're saying that those rainfall events, they're stronger, they come at different times of the year, they may last longer. Same with drought. These are situations that are not uncommon, but they are going to be longer in duration. They're things that we're going to have to begin to change the way we approach things because history would not have set us up to understand how quickly these things might be ameliorated.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take a few phone calls for our guest in the Climate Story of the Week for this week, Stephen Hammer, founding CEO of the New York Climate Exchange. We'll explain what they actually do in a minute. 212-433-WNYC. The premise is things might not be all that bad in Trump 2.0 for the climate, but it's also going to depend on climate action by advocates as well as by the marketplace.

He says the marketplace is pretty strong in terms of the impetus to keep going in the pro-climate direction that we're going. What do you think, or what question do you want to ask? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Call or text. This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York, WNJT-FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are New York and New Jersey Public Radio and live streaming at wnyc.org. Now here's that other Chris Wright clip, the energy secretary nominee.

Chris Wright: There is no climate crisis. and we're not in the midst of an energy transition either.

Brian Lehrer: It's the second part of that. Obviously, you'll disagree with the first part that there's no climate crisis, but he says we're not in the midst of an energy transition. Trump campaigned on drill, baby, drill. Remember, he said one of the few ways that he would be a dictator on Day 1 is that he would order drill, drill, drill, which is obviously not in the interest of mitigating climate change. How do you hear that clip, and how would you talk back to that?

Stephen Hammer: Well, again, I think it comes back to there's a belief that some circumstances are just not happening, and it may be a matter of geography. I would argue, and I think the evidence is there, that we are already beginning to see a shift in the way we generate electricity in the United States, whether it's from wind power, whether it's from solar. We now are talking about hydropower coming down from Canada to power our lights. We're seeing transitions in terms of the kinds of vehicles that people are purchasing. We're seeing changes in the way that people want to heat and cool their buildings through heat pumps.

These are market conditions that are beginning to change. Manufacturers are ramping up their production capacity. There has been a dramatic increase, not just in the United States, but globally in all of these areas. I was at the World Bank during Trump 1 administration, and despite the fact that he wanted the world to go a certain way, the reality is that countries around the world were voting with their feet. They were saying, "We demand change. We are facing circumstances we haven't seen before. We need help on that. We want to transition to cleaner energy. We want help on that." He cannot deny that.

I think that's where they're going to be missing the boat, and we're going to end up in a situation where people who are making those investment bets and going back to the old ways of doing things are going to end up with assets that are losing value and ultimately are meaningless in the not-so-distant future.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a text from a listener who says, "I appreciate the juxtaposition of Trump's first term to this one, putting aside what he thinks might not happen. What are the ramifications of what he wants to do, and in what ways could Trump use tools of government to impact the environment, even with private interests, the private sector wanting otherwise?"

Stephen Hammer: Look, the government does have power of subsidies. You can look at what the Biden administration has done through the Inflation Reduction Act. There was an announcement this morning that there was going to be a major loan provided to an electric car manufacturer to set up a huge plant in Georgia. If you stop those, the market may respond in some ways, but again, that's not going to change the macro signals globally. The US is either going to be in the lead or it's going to find itself behind.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call from Alan in Brooklyn. Alan, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Alan: Good morning, Brian. Thanks very much. It seems to me that the president's denying the reality of climate science. Not so much to try to stop technological change by business, which is following the profit motive, but to set up a barrier against mega tort liability claims against industry for climate damage the way attorneys for a defendant would deny all the allegations of a plaintiff at the beginning of a trial and make the other side prove every contention because the climate transition is happening. It's happening around the world, it's profitable.

What they don't want to have is an admission of the need for that that would lead to a greater pressure for mega tort liability claims that would dwarf the tobacco liability claims of the late '90s.

Brian Lehrer: That's an interesting question. Do you have your eye on this at all, and do you think the administration can somehow hold off civil suits intended to go after climate polluters? We have a interesting text on this from a listener too, just kind of speaking back to that clip of Chris Wright. It says, "To Mr. Wright, so why has my boat insurance doubled in the past few years?"

You could see something like that being part of a damages lawsuit by citizens against climate polluters. "Look what you're doing. Look what you're costing all of us with your refusal to stop causing climate change."

Stephen Hammer: Well, I think that if you look at the law schools around the area-- Pace has one of the top law schools focused on environmental and climate issues, and they've been sending people to different legal gatherings. They were at the COP a couple weeks ago. If you went to the sessions there, you were hearing about the progress that's being made in international jurisdictions and European courts. I think that was a very astute observation by the caller, and I think there probably is some validity in terms of what they're trying to forestall.

Whether that's going to fly from now for the next several decades, that's really hard for me to anticipate. I think we are reaching that point. Again, that text you just read is again the kind of data point that all of a sudden introduces the opportunity for class action lawsuits who are saying, "Refute this evidence. This is a result of increased storm severity, increased likelihood that my boat's going to be damaged. I need to hold someone accountable for that." Who's accountable? The people who are actually putting the pollutants into the air.

Brian Lehrer: In your op-ed, you outlined three ways to continue climate action while also saving lives and creating economic growth. One of them is, you write, climate impacts are bipartisan and communities pull together to rebuild after a fire or storm, regardless of political viewpoints. Talk about building coalitions during Trump too, as you see it.

Stephen Hammer: Great opportunity for me to talk about the New York Climate Exchange. We are, at the very core, all about collaboration, about bringing different communities together, whether it's academics and business and community organizations trying to figure out new ways to engage and work together to act on climate change. I think we're going to see more and more and more of that. I'm not saying this is the first time it's ever been tried. We can all point to lots of examples where academics have partnered with business or academics have partnered with communities to try and deliver change or understand why things are happening.

Now we're talking about sitting down, having extended conversations, not just a short-term consultation, but something where we're actively trying to take account of each other's perspective and come up with the solutions that are actually going to work, that are going to deliver big impact, that are financeable, that actually deliver equity and justice concerns, which are often missing from these conversations. The Exchange is all about focusing and prioritizing on those kinds of approaches.

Brian Lehrer: What are some local New York City or New Jersey or Connecticut resources, places in our listening area that might both be resources and keeping our listening area competitive with the growing climate tech sector?

Stephen Hammer: Well, there's a lot of resources. The Exchange is built up, again, of academic, private sector, and community partners, 48 in total. The vast majority of them are local. We are banding together to try and identify what are the issues that can really deliver a demonstrable positive benefit in our communities. Look at stormwater management. This is something the city has really made tremendous strides in recent years of trying to understand and begin to make investments that will address that, but as storm severity grows, people are going to have to begin to take action on their own.

The Exchange is in a really good position to try and help bring communities together, to provide the educational materials, to talk to people about steps that they can take to help them understand where they can find the resources to actually pay for these changes to their facility, to their home. We very much see ourselves as a resource bringing that information and ideas and making it broadly available to the public.

In terms of this question of how to keep New York competitive, well, again, thanks to city leadership, thanks to Mayor Adams and the Green Economy Action Plan, you have a long-term vision for where New York City can go, how it can actually capitalize on the transformation that lies ahead. You want cleaner air? That means we have to change out the technology we're using to power our lights but also power our cars and also heat and cool our homes.

That means that you have to change out some of these technologies. That means we're going to end up with less pollution in the air. All of those things are going to introduce a greener economy, creating new job opportunities for all kinds of New Yorkers.

Brian Lehrer: Last thing, do you think there's a big battle ahead regarding the Biden administration's Inflation Reduction Act, which was called the Inflation Reduction Act, but more than anything, it was the biggest climate change law that the US ever produced. You wrote corporate investment in climate action grew during Trump's first term because of the market demand, particularly for decarbonization and mitigation projects. That was during Trump's first term. Then came the Inflation Reduction Act.

I think Biden is trying to get as much money out the door as possible to actually get as many of these green energy projects going as possible before Trump comes in and tries to stop some of them. I'm just curious what kind of battles you see once the inauguration takes place.

Stephen Hammer: As you mentioned, the administration is very focused on getting money out the door, but they were also very focused and strategic when they set this thing up to try and make sure that the money couldn't be clawed back in the future. I think they're trying to dot the I's and cross the T's to make sure that's actually the case. Now, one of the challenges is that when you've got people who are really interested in pulling back on that, they will try all types of things.

You never know in courts whether-- judicial appointees who may be friendlier to a new administration, whether they would go against, try and undermine some of those efforts by the current team, but I think we have yet to see how far he's really going to go. Again, that battery or the Rivian plant in Georgia, that's in a red district. Most of the IRA money has gone out to red districts around the United States.

Even those congressional representatives who voted against IRA are often the first ones to show up in that photo op because they're claiming credit for those jobs that have come to their community. Will that mean that there will actually be opposition to pulling back from these kinds of things? I think there's a good chance that we'll see that.

Brian Lehrer: That's our Climate Story of the Week. Stephen Hammer is the founding CEO of the New York Climate Exchange and he's co-author of an op-ed in the Miami Herald titled The Trump Administration Is Not Necessarily Bad for Climate Change. Thanks so much for coming on.

Stephen Hammer: Thank you very much. Appreciate it.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.