100 Years of 100 Things: The Great Gatsby

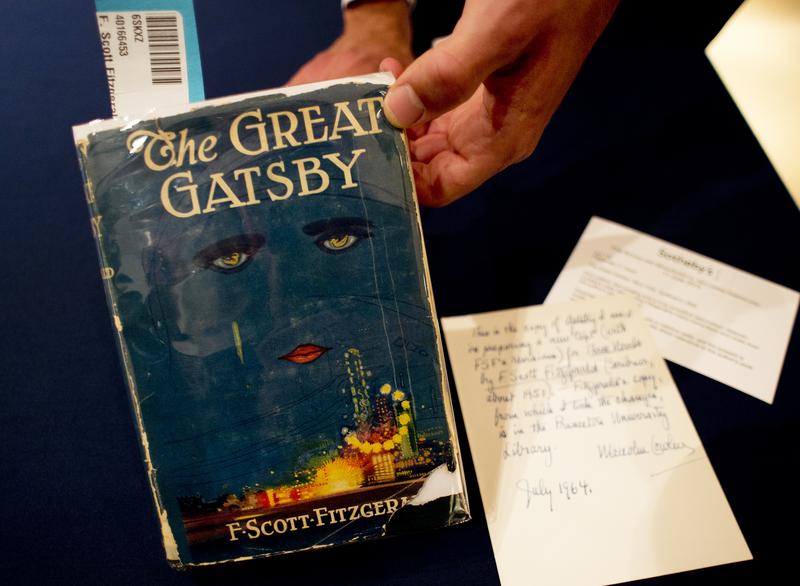

( Don Emmert/AFP / Getty Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Now we continue our WNYC centennial series, 100 Years of 100 Things. Today it's thing number 58. 100 years of F. Scott's Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. This year marks the 100th anniversary of one of the most iconic novels in American literature. That's why we're doing it as part of this series. Though it didn't receive much attention when it was first published in 1925, it has since become a cultural touchstone, taught in schools and endlessly reinterpreted in art and film and even fashion.

We're going to play you a couple of clips from movie adaptations. Why does Gatsby continue to resonate a century later? Well, joining us to explore the lot, the novel's lasting cultural and literary impact and what it might still have to say about America's political, social and economic predicament, is Maureen Corrigan. You may know her as book critic for Fresh Air. She's also a Georgetown professor and author of the book, So We Read on: How the Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures. Maureen, thanks so much for coming on for this. Welcome back to WNYC.

Maureen Corrigan: Thank you so much, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Fitzgerald apparently called the 1920s the most expensive orgy in history. We see that extravagance all over the Great Gatsby. That's one of the things that has people comparing those times to these times with the concentration of wealth and extravagance in today's billionaire class. What was the economic and cultural context in which Fitzgerald wrote his masterpiece?

Maureen Corrigan: Yes. We have to remember Fitzgerald and his generation were coming out of World War I. They were also coming out of the flu pandemic. There was that urge to forget everything, party, feel alive again, drink to excess, dance to excess. I think of the film clips that we have of the dances of the 1920s. Everything is very fast and restless. By the way, restless is a word that Gatsby, the Great Gatsby uses over and over again. No one can sit still in that novel. There's that sense of hedonism and living for the moment. Then there's also the undercurrent of knowing that the party can't last.

Fitzgerald always has this double sensibility. I think he was absolutely able to lose himself in drinking and partying, as we know, but he also could stand back. As The Great Gatsby tells us, there is going to come a time when the lights are going to go out on the national party. The novel is very prescient, honestly, about the coming of the Great Depression. You see that in the last third of the novel. I feel like that doubleness is something that really corresponds to our own age. People are buying too much and again, trying to lose themselves in streaming shows, and entertainment. We also have this sense of dread about what may come next.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I think I assumed a certain amount of familiarity in the intro because it seems like everybody who ever went to high school has been assigned this book in English class. It's a skinny enough novel that maybe this is one we all actually read instead of going to the Cliff Notes or the Spark Notes. For those who haven't, maybe take a minute here to do a very basic introduction of The Great Gatsby for someone picking it up for the first time. Is it primarily a love story, which it is. A tragedy, which it is. A mirror held up to society, which it is.

Maureen Corrigan: All of the above. It's the story of a man named Nick Carraway who is carried away by his love and his regrets and his memory of his friend Jay Gatsby. The first thing to know about the novel is that everything in the novel, all the events of the novel, have already transpired. When we begin the novel on page one, Nick is our narrator, and he is remembering the summer of 1922. He tells the story of Jay Gatsby, who began life as James Gatz, a poor boy, who fell in love with a rich girl, a typical Fitzgerald plot, named Daisy, and lost her. Gatsby, when the present time of the novel in 1922 occurs, Gatsby is trying to win her back.

By then he's made a fortune in bootlegging and other nefarious activities. Daisy, who is married to Tom Buchanan, is intrigued by this titanic love that Gatsby has for her. For a while, they're together until everything blows up. Daisy's love is limited, Gatsby's is not. In the end, Gatsby dies. I'm not giving anything away because as I always tell-- Sometimes I speak at high schools and the students gasp when I say, "Gatsby is dead." On page two of the novel we're told that. They gasp. That means they haven't read the novel.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Got you. Plus, if you can't do spoilers on a work of art, that's 100 years old, then the rules are too strict. Fitzgerald was only in his 20s when he wrote the book. Was he having next gen insights that older writers or other commentators were blind to? That seems to happen in every generation.

Maureen Corrigan: It does. I do feel like there is this eerie quality of prescience in the novel. Especially, as I said, when you get to the last third of the novel where the lights are turned out in Gatsby's house, where the parties are over, there really seems to be this sense of the novel speaking to more than just what's happening in Gatsby's private life, but also what's going to happen in America. In fact, if I can just throw this out too, there's a biographical quality of prescience when Fitzgerald describes Gatsby's funeral where hardly anyone shows up and it takes place in the rain and the minister mumbles and doesn't know who he is. That was Fitzgerald's own funeral in 1940 when he died at the age of 44. Took place in the rain. Hardly anyone was there. The minister really didn't care about him.

Brian Lehrer: Isn't there a biographical thing where hardly anybody came to Fitzgerald's sixth birthday party? Do I have that right?

Maureen Corrigan: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe that's what planted the seed for nobody came to Gatsby's funeral.

Maureen Corrigan: Yes. You always have this sense when you read Fitzgerald's letters and even his other writings, especially the crack up his later writings in the '30s when he was really struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts. You really have this sense of him always being an insider, outsider. He said this himself. Gatsby is our greatest novel about class. Fitzgerald himself was very aware of, as he said, being a poor boy in a rich neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota. Being a poor boy at a rich school at Princeton. Always that sense of wanting to be on the inside and yet being separated from other people by a pane of glass.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take your calls in this 100 Years of 100 Things segment, number 58. 100 Years of The Great Gatsby, which was published in 1925. I wonder who out there thinks you're the person who read The Great Gatsby the most recently. If so, how would you relate it to conditions in our country or anything it has to say that's relevant to conditions in our country today? 212-433-WNYC. That might be a needle in a haystack and we won't get any calls, but let's see. If you think you might be the person who read The Great Gatsby the most recently call in. Maybe it was your kid in their high school class a month ago. That's okay too.

212-433-WNYC. Let's see if we get any calls like that. If we don't, then we'll broaden the ask. 212-433-WNYC. If you think you have read Gatsby in any period of time that you would call recently, maybe even the most recent reader listener. 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692. Meanwhile, here's a short clip from one of the more recent movie adaptations of The Great Gatsby, Baz Luhrmann's adaptation, which some say was ridiculous adaptation in 2013. In this scene, which runs about a minute, Nick, played by Tony Maguire, is meeting Gatsby, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, for the first time at one of Gatsby's extravagant parties.

Nick Carraway: I live just next door. He sent me an actual invitation. Seems I'm the only one. I still haven't met Mr. Gatsby. No one's met him. They say he's third cousin to the Kaiser and second cousin to the devil.

Gatsby: Afraid I haven't been a very good host on sport. You see I'm Gatsby.

Nick Carraway: His smile was one of those rare smiles that you may come across four or five times in life. It seemed to understand you and believe in you just as you would like to be understood and believed in.

Brian Lehrer: A grand entrance for the Great Gatsby. Maureen, I think there have been five movie adaptations and I don't know if any of them are considered successful or good. Where are you on that?

Maureen Corrigan: No, they're not successful or particularly good. My favorite is the 1949 version starring Alan Ladd, which maybe listeners of a certain age will know that Alan Ladd was famous during the golden age of Hollywood for playing cowboys and gangsters. That 1949 version is so interesting because it really does emphasize the fact that Gatsby's wealth is grounded in dirty business, bootlegging, murder. I think there's something to be learned from that version. I did not like the Baz Luhrmann’s version. I thought it made the cardinal error of really celebrating the parties and the wretched excess and not looking enough at what lies beneath that shining veneer.

Brian Lehrer: On the timeline, the book was not a hit right away. I don't even know if they had bestseller lists yet in the 1920s? You, as a book critic maybe could tell me. I see the book started to be considered particularly important in the 1950s. If I have that right, why then if we think of the '50s as a generally complacent time, at least in white America, of accepting the American Dream as real and not much mainstream social criticism, like we see in Gatsby?

Maureen Corrigan: Well, I'll throw out two reasons. Gatsby has it both ways. It celebrates aspiration, the American Dream, the promise of meritocracy, and it also undermines our faith in the American Dream. The primary dreamer, Gatsby, ends up dead. That's not too reassuring. There's that. It's not completely-- It's not a cynical novel in its totality. The other reason, I think, goes back to World War II. Gatsby was basically off the bookshelf elves in the 1940s. There are stories about Fitzgerald going into bookstores and trying to buy Gatsby to send a copy to friends and not being able to find a copy.

You have this amazing program during World War II in which these little books called the Armed Services Editions were distributed to soldiers and sailors serving overseas. Gatsby was one of the titles that was chosen. 155,000 copies of The Great Gatsby were distributed at the end of World War II. there's a groundswell of interest, I've actually heard, from some guys who served during World War II when my book came out in 2014, and they said that that was when they were first captivated by Gatsby. I don't think we can underestimate the fact that the ordinary Joe picked up Gatsby and thought and saw something in it. Then, of course, you get the paperback revolution after World War II, and Gatsby was one of the first paperbacks that was published by Signet.

Brian Lehrer: You're telling me that it was the Pentagon, of all things, that revived Great Gatsby and set it on its course as being seen as the great American novel for people coming back from D Day. That's crazy.

Maureen Corrigan: It's crazy. I would recommend to any listeners interested in this amazing story about what books did during the war effort in World War II. Stephen Ambrose's book on D-Day, called D-Day has a whole section about the Armed Services editions being distributed on the eve of D-Day and the Service those little books performed during the war.

Brian Lehrer: Sean in North Plainfield, you're on WNYC. Hi, Sean.

Sean: Hello.

Brian Lehrer: Do you think you're maybe one of the most recent readers of Gatsby in our listening audience today?

Sean: Maybe, maybe not. I read it about a year ago.

Brian Lehrer: in what context?

Sean: I read it for school.

Brian Lehrer: What grade are you in?

Sean: I'm a junior this year.

Brian Lehrer: Cool. What's the first thing you would say about that book to somebody who hasn't read it or what sticks with you a year later?

Sean: What sticks to me is its relevance today. It's very-- The tale of the American Dream is still relevant today and how it can be reached and even if it can be reached today.

Brian Lehrer: What do you think? Did it make you more pessimistic or more optimistic about the country, or neither?

Sean: I think it continued my understanding of America today and how the world works and all of that.

Brian Lehrer: Sean, thanks a lot. We really appreciate you calling in. How about that, Maureen?

Maureen Corrigan: Well, I think he's right. As I said, the novel is not flatly cynical. It has it both ways. Some of the other aspects that correspond to today, of course, are the facts that the novel is obsessed and anxious about immigration. It's anxious about race. It's anxious about women who, as we know in the 1920s, they're voting, they're smoking, they're drinking. All of those anxieties are our anxieties that we have seen rise up again in our own time.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, also, how about that they're still teaching it in high school. We just had a junior in high school call in and said he read it last year.

Maureen Corrigan: Of course. We have to acknowledge that, as you did at the outset, that part of the reason is that it's so compact. One of my old students once said it's the Sistine Chapel of literature in 185 pages. I asked him if I could steal that for my book and he said yes, so I did.

Brian Lehrer: My guest on 100 Years of The Great Gatsby is Maureen Corrigan, book critic for Fresh Air, Georgetown professor, and author of So We Read on: How the Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures. Paul in South Orange, you're on WNYC. Hi, Paul.

Paul: Hey, Brian. How are you today?

Brian Lehrer: Good, thanks. What you got?

Paul: Well, I have been reading and rereading Gatsby since back to my high school days. I Read it in college. Revisited it as an adult. Revisited it with my kids. I always read the text less as Fitzgerald's critique of the American Dream and how it's all just no trash. I always read it as his take on the utter hypocrisy of humanity. He is indictful of everyone. That's one part of it. The other part of it that I read was, Nick's not reliable. Nick is not a reliable narrator. It's all seen through his eyes, through his perspective. He's part of the grift. In college, we started to talk a bit about, the queer theory aspect of it is, is he in love with Gatsby?

Does he depict Gatsby in an overly romanticized way that impacts his love of his lifestyle, his romantic love for him? I don't remember seeing the Alan Ladd version, but I remember the Redford Farrow version in the '70s. That was filmed through so much gauze, you barely can see their faces, both literally and figuratively. I think what started to happen in the '70s and the '80s and '90s, the glamour part of it-- Without quoting another classic, Holden Caulfield, they're all phonies. From the gas station attendant all the way up down to. It doesn't matter if you are living in a hovel by the side of what became Jericho Turnpike or you're living on the Upper East side. They're all phonies.

I have great respect for it. Now that it's in the public domain, I point out to friends, "Hey, if you lost your copy from high school or college or whatever, go online--" It seems like with the Broadway musical, they're now selling tickets into next year, there's going to be another Broadway musical. There are going to be annual productions of Gatsby in every shape and form. The way that part of the Gershwin.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. With the Centennial. Well, thank you for that deep take, Paul. Really appreciate it. Before I ask you to respond to that, Maureen, here's a clip from the movie version he referenced. This is from 1974, directed by Jack Clayton, starring Sam Waterston as Nick and Robert Redford as Gatsby.

[music]

Nick Carraway: I thought of Gatsby's wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy's dock. He had come a long way to this lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him.

Brian Lehrer: That's a young Sam Waterston as Nick Carraway. Maureen, to the caller's point, or a couple of his points, that Nick is an unreliable narrator, the book is in his voice, and that maybe there he had a queer crush on Jay Gatsby. Have you looked at through that lens?

Maureen Corrigan: Oh, of course. That's a very popular lens to look through the novel at these days. I would say I think the caller is right, that everyone is flawed. I disagree with the caller when he says everyone is a phony. I think about what Nick says about Gatsby, that he had an extraordinary gift for hope. Sure, Nick lies to us about a few things, including a prior engagement that he doesn't tell us about right away at the beginning of the novel. I think you feel the truth of Nick's love for Gatsby in statements like that, in the way he talks about Gatsby and whether that love is erotic or not. It could be, but I almost feel like the love that Nick has for Gatsby is almost beyond eroticism. He worships Gatsby the same way Gatsby worships the green light.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. to the Broadway version that the caller referenced, listener texts, there's a wonderful musical currently playing on Broadway of The Great Gatsby written by composer Jason Howland and book writers Kate Kerrigan and Nate Tyson, starring Jeremy Jordan. It's really quite wonderful and is doing very well, writes that listener reviewer. I don't know that we've mentioned yet explicitly the fact that Gatsby is set largely on Long Island. here's Anne in Great Neck with something on that, I think. Ann, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Anne: Hi. Thanks, Brian. I've called in before a couple times on local politics, so this is a bit of a switch for me. Maureen, I want to thank you for your Fresh Air reviews. You have sent me to many books that I would not otherwise have read. I live around the corner. Oh, you're welcome. I live around the corner from the house where The Great Gatsby was written. it's a little larger than some of the houses in the area, but it always attracts attention in international real estate markets when it goes on the market and it sells for a lot more than it would otherwise. I always find that interesting that people still has some currency, literally.

The other thing is a few years ago, a friend of mine asked me if I wanted to go on a Great Gatsby boat tour with her, through Long Island Sound, on the north shore of Long Island. I said, "Sure, why not?" It was really eye opening. The houses are on the water, are huge, and they showed us the green light or where the green light was supposed to be and all that. I think it's actually Little Neck and Great Neck where that took place. In any case, what was amazing to me was you see these houses from the land and they don't look that exceptional. You see them from the water and they are vast. Many of them have been rebuilt since the time of the book, but the culture's still there.

Brian Lehrer: Great call. we could even throw Robert Moses into this conversation at this point. Because of its Long island setting, Robert Moses is in a certain way, not by name, but in a certain way present in this story. I think the Valley of Ashes and Gatsby became the real life site of the 1939 World's Fair. Anything on that or to Anne's call?

Maureen Corrigan: Well, first of all, Anne, I too took The Great Gatsby boat tour of Long Island Sound. I agree with you that being able to see the geography of East Egg and West Egg from the water really made me appreciate how much Fitzgerald was relying on fact. You really can see the skyline of Manhattan from the tip of West Egg where Gatsby's house was supposed to be located. That geography is very true to life still. Yes, Robert Moses. Well, what do we associate Robert Moses with? Car culture. Cars. Cars. Cars are crucial to the plot of The Great Gatsby.

Again, the characters keep restlessly commuting between Long Island and Manhattan in this novel. In fact, at the very end of the novel, on the hottest day of the summer, they come up with a preposterous suggestion that everyone should pile into two cars and drive into Manhattan because no one can sit still. There's this, I think, Post World War I antsiness about the novel that makes everyone too restless to stay still for very long.

Brian Lehrer: ADHD, before the Internet, 1920s. Have there been any book banning attempts aimed at The Great Gatsby?

Maureen Corrigan: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: From the don't criticize the American dream. Right. To the wounded by racist or anti-Semitic language left, because there is some offensive stuff in there.

Maureen Corrigan: Yes, absolutely. The character of Wolfsheim, who is, a bootlegger, a money lender who, he's described almost like a shylock figure who wears human molars as cufflinks. Presumably if you don't pay him on time, he pulls out your gold fillings in your mouth and wears them as his cufflinks. No, there's lots of offensive stereotyping in the novel, racial stereotyping, but the book banning attempts that I know of mostly target the drinking and the extramarital sex and some of the language. Fitzgerald uses a lot of slang in Gatsby, which is interesting.

We think of the language as being so gorgeous and elevated, but he's also using a lot of '20s slang. That's what I've seen targeted I in classroom discussions because I teach Gatsby every year, we get more into some of the students discomfort with the character of Wolfsheim, with how people of color are imaged in the novel. Those criticisms, what you might say from the left, come up in classroom discussions.

Brian Lehrer: Why does it deserve to live, in your opinion, in classrooms in that context?

Maureen Corrigan: Because every great American novel that we can think of is a product of its time. Every great American novel from Moby Dick to Invisible Man keep going. Every great American novel will reflect some of the biases, the anxieties of its own time. we need to preserve that language to understand the context, the historical context out of which those novels grow. They also transcend their time. Boy, does Gatsby transcend its time. You're talking, we're talking, a lot about the cultural and economic context of Gatsby these days. Does this novel express the beauty of stretching out your arms and trying even though you know you're going to fall short? That's not a time bound gesture.

Brian Lehrer: I don't know if you're prepared to do this, but maybe when we come back from a break, because I know you've written, elegantly and exuberantly, about the prose in this book. I don't know if you have it there and want to pick out one little passage to read. You don't have to, but think about that. We're going to take a short break and then continue till the end of the hour because there are so many calls and texts coming in about The Great Gatsby at 100 years old. To give you a little preview of one or two that I may follow up on with you after the break. Denise in Richmond, you're going to be the next caller, so be ready.

One listener writes Maureen, "The character Tom Buchanan is definitely Maga and Nick's assessment of the Buchanan says, careless people is very much of this time today." You'll also be happy to know that somebody texted. "This segment has inspired me to suggest my book club read Great Gatsby for its 100th anniversary." Listener adds, "I'm a proud member of the Sunset park branch of the Brooklyn Public Library." All right. All that coming up right after this. Stay with us. It's 100 Years of the Great Gatsby and 100 Years of 100 Things series today with Maureen Corrigan. Many of her as book critic for Fresh Air. She's here in the context of being the author of So We Read on: How the Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC in our 100 Years of 100 Things series. Thing number 58, 100 Years of The Great Gatsby, which in fact came out in 1925. Our guest is Maureen Corrigan, book critic for Fresh Air, Georgetown professor and author of So We Read on: How the Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures. Maureen, do you want to talk a little bit more about why you love not just the social and political prescience of the novel, but also the writing. Then I see you did pick out a passage during the break, so that's great.

Maureen Corrigan: I did pick out a passage, yes. Well, I love the novel because it's inexhaustible. Some of us have read it 100 plus times, and I swear to you that there's always something new that emerges. Either some, in my case, some of my students will bring up words or passages or tones that I haven't been aware of in the novel, or I'll stumble upon something new. I think that's one great definition of a great work of art, that it never exhausts itself. I did pick out a passage, and this is a paragraph on the last page of the novel. Nick is standing at Gatsby's house on West Egg, looking toward the Manhattan skyline.

I'll just say, here's where you know in these last pages of the novel that Fitzgerald is aiming for something bigger than just writing about a love affair. He's aiming to say something big about America. This is Nick. "Most of the big shore places were closed now, and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferry boat across the sound. As the moon rose higher, the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailor’s eyes, a fresh green breast of the New World.

Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby's house had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams. For a transitory, enchanted moment, man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired. Face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder."

Brian Lehrer: Wow.

Maureen Corrigan: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: It's beautiful. It's deep. It's philosophical, and it's very New York.

Maureen Corrigan: It's very New York. I grew up in Sunnyside, Queens. I grew up, I went to high school in Astoria. It took me a long time to realize that this novel was set basically in my home area because it has that quality of being so artificial, so beyond. Yet you're right, it's very New York.

Brian Lehrer: on the topic of reading Gatsby out loud, here's John in Brooklyn. John, you're on WNYC. Hello.

John: Hi. Thanks for taking the call. Yes. I am one of these who have adapted the Great Gatsby into a performance. My company, Elevator Repair Service, created Gats, which I directed, which is a performance of every single word of the novel, start to finish in a single day. An eight hour performance. what I wanted to offer about the-- What makes the novel enduring comes very much from my experience of hearing it read aloud verbatim over 200 times. This is more than a novel about flappers and '20s parties and glamour and glitz. even, I'll go out in a whim and say, even the American Dream.

This is just a beautifully constructed, beautifully perfectly written novel. I think if you want to know why this novel endures the way it has, just read it. It takes about five and a half hours. Just read it. It's everything you need to know about why it's great. You won't learn it from people who rewrite Fitzgerald's words to fit their movies.

Brian Lehrer: John, thank you. Thank you very much. I'm going to go right on to Denise. Richmond, Virginia, you're on WNYC. Hi, Denise.

Denise: Hi, Brian. I'm a longtime listener, lived in New York for 43 years and moved back down to my hometown of Richmond, Virginia and still listen to you every morning.

Brian Lehrer: We can hear the Virginia in your voice. You didn't lose it.

Denise: Oh, can you? I think it's just because I've moved back down here.

Brian Lehrer: I'm glad you're still out there. What have you got?

Denise: Talking about, , the last time you read it, which is what inspired me to call you. We got some snow down here last week and we haven't had a big snow in a long time. Of course I went, I had to get the book off the shelf and read the passage where Fitzgerald talks about Nick Carraway going back to St. Paul and the snowflakes on the train and how the weather changes. Then, of course, the prose is so wonderful, once you pull the book off the shelf, you're stuck. Then I had to reread the whole ending of the book again. I think I read from the time they find Gatsby in the pool onward.

It's just so beautiful no matter where you are. In terms of its relevance to what we're living in today, I think I would say that the callousness, not necessarily just the carelessness, but the callousness of people like Daisy and Tom are what strikes me in our present situation.

Brian Lehrer: Wow. What a great call, Denise. Thank you. Thank you very much. The callousness, not just the carelessness. She could be a writer, too. Connecting it one more time and one more way to today in our last minute, Maureen, that listener who wrote that the character Nick is definitely Maga. Do you agree?

Maureen Corrigan: No, they said Tom is Maga, not Nick.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, Tom. I'm sorry. Of course, yes.

Maureen Corrigan: Yes, of course. The first time we see Tom, he's spouting off half-digested theories about race, about eugenics, and he points at everyone at the dinner, Nick and Daisy and Jordan Baker, who we haven't talked about, and says, "We're all white here. We're part of the superior race." Tom is very worried about, as he says, the white race becoming submerged. I don't even have to draw the connection to today, do I?

Brian Lehrer: No, you don't. With that rhetorical question, we leave it with Maureen Corrigan, book critic for Fresh Air, Georgetown professor and author of So We Read on: How the Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures. That's thing number 58 in our series, 100 Years of 100 Things.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Today it was 100 years of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, which was published in 1925. Maureen, you were fabulous. Thank you so, so much. We'll hear you on Fresh Air.

Maureen Corrigan: Thank you, Brian. It was a pleasure.

Brian Lehrer: That's The Brian Lehrer Show for today. Produced by Mary Croak, Lisa Allison, Amina Cerner, Carl Boisrand and Esperanza Rosenbaum. Megan Ryan is the head of Live Radio, Juliana Fonda and Milton Ruiz at the audio controls. Stay tuned for Alison.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.