100 Years of 100 Things: Jimmy Carter

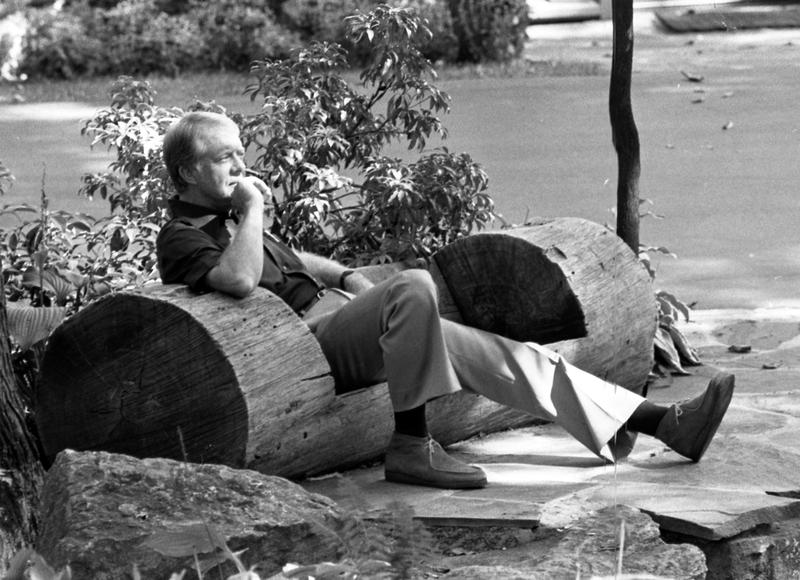

( Jimmy Carter Presidential Library )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, again, everyone. Now we continue our WNYC centennial series, 100 Years of 100 Things. Today it's thing number 25. We're a quarter of the way there. It's a happy birthday edition of 100 things, because just like WNYC, former president Jimmy Carter was born in 1924, and tomorrow, October 1st, will be his 100th birthday. Happy birthday, President Carter, first of all. His health has reportedly been failing, but it's also been in the news that he's been wanting to stay alive at least long enough to vote in his home state of Georgia, the swing state of Georgia to help Kamala Harris win the election.

He'll need a few days past his 100th birthday for that. Mail in ballots go out in Georgia 29 days before the election so that will be one week from today if I did my math right. In this 100 years of Jimmy Carter segment, we'll do three things. First, we'll talk about his early years, the remarkable American story of someone from pretty humble and obscure beginnings making it all the way to president. How did his childhood set the stage for that? We'll also replay an appearance by Carter on this show from 2010, a time when he had the courage, I'll call it the courage, to write a book about and do whole interviews about arguably the worst thing in his presidency, the Iran hostage crisis, which began in 1979.

The American hostages weren't released until Ronald Reagan was inaugurated after defeating Carter in 1981. Here we still are, of course, with Iran and the US still basically at war, depending on how you define it, with so much killing and hostage taking around the Middle East. We'll get to that 2010 interview with Carter in a few minutes. We'll also touch on his widely praised post presidency. Our guide for 100 years of Jimmy Carter is Jonathan Alter, MSNBC analyst, author of the substack newsletter Old Goats, author of several books about presidents, including FDR, Obama and His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life which came out in 2020. He also has a forthcoming book, American Reckoning: Inside Trump's Trial - and My Own. Jonathan, welcome back to WNYC.

Jonathan: Thanks for having me, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: How humble or how much born into a leadership family in Plains, Georgia was Jimmy Carter's childhood?

Jonathan: Well, it was an affluent family for the area, for the time and for the area. His father was a successful merchant and farmer, also a white supremacist. His mother was a nurse and the only person in southwest Georgia who had anything nice to say about Abraham Lincoln. She was a liberal who was a real fish out of water and gave her son his racial enlightenment and also his interest in public health. At the time, for the first 11 years of Jimmy Carter's life, he had no running water, no electricity, no mechanized farm equipment. He was barefoot for most of the year and not affluent in the way we would define it now, although more so than his neighbors.

Brian Lehrer: Now, in a PBS documentary, historians outlined how Carter's father, Earl Carter, who you just called a white supremacist, had his land farmed by sharecroppers, a system really just one step away from slavery. At the same time, his mother, Lillian Carter, would give free healthcare to her Black neighbors, and young Jimmy would work and play alongside his Black friends. You write about this in your biography of him. Here's a 40-second clip of Carter in conversation at a national archives event in 2016.

President Jimmy Carter: I grew up during the Great Depression years on a farm. All my neighbors were African American, and all my playmates were Black. The ones with whom I worked in the field were Black. Until I was a teenager, I never realized that they had mandatorily separate and unequal schools. I never realized that their parents couldn't vote. I never realized that my playmates parents couldn't serve on the jury, that they were deprived of basic rights. It was a time for me to learn all about that.

Brian Lehrer: Jonathan, how did Carter's childhood and perception of race in his childhood shape his views as an adult and his presidency as an adult?

Jonathan: Well, I think that he had a longer journey to enlightenment on these issues than maybe some people assume. He never used the N word, for instance, that anybody can remember. From a very early time, he followed his mother in her compassion toward their Black neighbors. He really had a third parent, a woman named Rachel Clark, who was an illiterate farmhand, not a sharecropper, but worked on the Carter farm, and she taught him his love of nature and gave him much of his faith.

Brian Lehrer: Black woman?

Jonathan: Black woman. From a very early time, he thought differently than other people. When it came time for him to return from the navy, where he had defended the first Black midshipmen at the US Naval Academy, stood up for his Black crewmates when they were discriminated against, nonetheless, when he came back and he entered into that very segregated, mean society in southwest Georgia, he couldn't move too quickly. For instance, he was chairman of the Sumter County school board, and I consulted the minutes of that school board and after the Brown versus Board of Education decision, they didn't even discuss integrating the schools.

Carter tried to work around the edges by providing some rickety used school buses for Black students so they didn't have to walk, but there was only so far that he could go. Then when he ran for governor, although he had rejected efforts by the White Citizens Council, the uptown Klan, they called it, the organization of racist business leaders, he rejected their efforts to get him to join the White Citizens Council when he was in Plains.

When he ran for governor the second time in 1970, he made nice to the founder of the White Citizens Council, and he said nice things about George Wallace, code words to his supporters in rural areas. He was running against a former governor from Atlanta. He was running to his right. I think Carter felt bad about that, and he never went too far. Literally, in the first minutes of his governorship, at the top of his inaugural address, he says, "The time for racial discrimination is over." This was a profound statement. Doesn't sound like much, but it landed him on the front page of the New York Times.

Brian Lehrer: This is 1971.

Jonathan: 1971. He went on to integrate Georgia government, and then when he became president, as governor, he put Martin Luther King's portrait in the state Capitol, which caused a big demonstration by the KKK. Then as president, he brought diversity to the federal government for the first time. There had just been tokenism before Jimmy Carter was president. He not only appointed a record number of African American judges, but he appointed five times as many women judges as all of his predecessors combined.

My argument is that he spent the second half of his life from age 50 on making up for what he did not do, i.e., standing up on race in the first half of his life. At one point when I was asking about this period, he said, "I never claimed, John, to be part of the civil rights movement." Then he went on to explain how he had made up for that.

Brian Lehrer: Well, now we've covered the first 50 years of his life. Ha ha ha. Or this one issue, and that reference to the dividing line for him being around age 50 with Jonathan Alter, author of the biography of Jimmy Carter called His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life in our 100 years of 100 Things series. Thing number 25 is 100 years of Jimmy Carter. The former president turns 100 tomorrow. Now we're going to move on to his presidency and do something different in this 100 years of Jimmy Carter segment. We're going to replay a full 14 minutes interview that Carter did with me on this show in 2010 about what was arguably the absolute worst experience he had in his presidency.

It was the standoff known as the Iran hostage crisis when the islamic revolution came to power in Iran in 1979. For those of you who don't know the history, didn't live through this or just don't know it, the supporters of the revolution were furious with the United States for having propped up the leader they overthrew, known as the Shah of Iran who they considered a despot and a traitor to his people and because the US was involved in an earlier Cold War era overthrow enabled by the CIA, and as one expression of that rage, a group of students and others raided the US embassy in Tehran and took the embassy staff and other Americans, more than 60 people, hostage.

Carter had recently allowed the Shah to come into the US for medical treatment, and I guess that was the last straw. Anything Carter tried to win the hostages' freedom failed, and they were finally released, almost in a literal last middle finger to Carter on Ronald Reagan's inauguration day, January 20th, 1981. 444 days of captivity for the hostages, an aura of weakness and failure for Carter that was a big key to his defeat, and the way a lot of people who were alive then really remember him. It's not the kind of thing that most former presidents would want to write a book and do interviews about, but Jimmy Carter did. The book was called Presidential Diary. It contained actual entries in his diary from during the embassy siege. Here is our full 14-minute conversation from September of 2010. After my introduction, I thank Jimmy Carter for coming on.

President Jimmy Carter: It's a pleasure.

Brian Lehrer: Let's begin with October 20th, 1979, the day you wrote in the diary that you admitted the Shah of Iran to the US for medical treatment, and you wrote that you simply informed the Iranian government of your decision, even though the State Department wanted you to ask their permission. Why did you reject the State Department's advice on that?

President Jimmy Carter: Well, I went back to President Brazigan and Foreign Minister Yazdi and got their commitment later on, which I got in the diary that they would protect American interests if the Shah came here, provided the Shah didn't make any political statements while he was in America, and he agreed to that. Later, when the hostages were taken, those two Iranian leaders resigned in protest because the Ayatollah Khomeini approved, in effect, the holding of our hostages. I had a complete understanding personally with the leaders in Iran that they would protect our interests there.

Brian Lehrer: The Iranian hostage crisis began on November 4th, 1979. On November 6th, you wrote in your diary that Khomeini was a crazy man, except that he does have religious beliefs and the name of Islam would be damaged if a fanatic like him committed murder in the name of religion against 60 innocent people. You wrote, "I believe that's our ultimate hope for a successful resolution." Looking back, of course, the hostages were not killed, but did you underestimate at the time what radicals were willing to do in the name of Islam?

President Jimmy Carter: I don't think so. I underestimated the length of time they would hold our hostages, but I didn't underestimate their threats against the hostages themselves. I sent word to Khomeini in November of '79 that if he put any hostage on trial, that we would interrupt all of Iran's commerce with the outside world, with blockades, with mining and so forth, and if he injured or hurt a hostage, then I would attack Iran with military force. Of course, he never put a hostage on trial, and he never hurt or injured a hostage either, although that was what they were threatening at the very beginning.

Brian Lehrer: I guess my question is really about the view of religion, in that case Islam, as a moderating force at the time, rather than a radicalizing force.

President Jimmy Carter: Well, I think it was. Although I was biased, I have to admit, when Ayatollah Khomeini approved the action of the militants, I've never thought that he knew ahead of time that they were going to invade our embassy and take our hostages as they did. I think he was caught by surprise but then later he found it politically expedient to go along with what they were doing. There's no doubt in my mind that their religion and also their fear of American retribution prevented their actually hurting a hostage. Later, one of the hostages developed a numb right arm, a young man from Maine, and immediately they released him to freedom, and he came by and I met with him. They were very careful not to hurt a hostage, and they never put one on trial.

Brian Lehrer: On November 18th, 1979, you wrote in the diary that Fidel Castro agreed to help win their release. Why was Castro willing to intervene for the United States?

President Jimmy Carter: Castro and I were reaching out to each other then. We both wanted to have full diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba, and we were able to get a lifting, I did, unilaterally of all travel restraints on Americans, which have now been reimposed, as you know. We ultimately put an intersection in Washington and Cuba. We now have diplomats, and they haven't been removed, although my successors have not been as friendly toward Cuba as I was. I think Castro was trying to do what was right, and he was also trying to be somewhat friendly toward me at that time.

Brian Lehrer: On November 27th, you wrote that your Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance, threatened to resign because you said you would put America's honor ahead of the hostages' release. Specifically, you would never apologize to Iran, hand over the Shah for trial, or pay reparations. Why were you against letting the Shah be tried in Iran for his alleged crimes as a ruler?

President Jimmy Carter: Well, I didn't think that we should succumb to blackmail and threats, to send the Shah back to Iran to be tried and executed was not something that I would have done. Also, I would never have apologized to the Iranian government because we had nothing about which to apologize, and I would never pay them ransom for hostages either. I was holding the American reputation intact, and so that was one of the criteria that I faced.

By the way, as I have all the way through the diary, Cy Vance threatened to resign three or four times before he finally did resign. Those were the pressures I had on me. There were tremendous pressures on the right wing for me to bomb Iran or to launch a military attack, which I think would have resulted in death of all our hostages, and there was some pressure on the other side to be more apologetic and so forth than I was inclined to do.

Brian Lehrer: Vance finally did resign, as you say, as your secretary of state on April 21st, 1980, saying he could no longer support your policy toward Iran. What were the specifics of what he could not support?

President Jimmy Carter: Well, Cy Vance had been involved, along with all of us, in planning the hostage rescue operation, which failed. He was completely immersed in the planning for that. After we launched the rescue operation and it failed, then Cy Vance resigned in protest, and I appointed Ed Muskie to be my secretary of state. It was a matter of personal disagreement. I might say, that of all my cabinet officers, though philosophically I was probably more compatible with Cy Vance than I was anybody else.

Brian Lehrer: Correct me if I'm wrong, but the impression that I got from the diary was that the precipitating incident was that the Methodist bishops denounced US policy, western imperialism, et cetera, in connection with the Iran crisis. You wanted Vance to intervene with them, and he felt he could not represent you in that. Is that correct?

President Jimmy Carter: That's one of the factors, yes. No matter who the secretary of state might be, no matter what his basic philosophy might be, it's an obligation for secretaries of state and all of the cabinet members to carry out the policy of the president, no matter how much they might disagree with it. The only alternative they have is to resign. Eventually, that's what Cy Vance did. Later, after I left office, Cy Vance was one of my best friends when I came to New York on a visit and so forth. I stayed in his house, slept with him and his wife and children. We were reconciled later on. He had honest differences of opinion about what we should do.

Brian Lehrer: Here we are 30 years later with President Ahmadinejad and almost a parallel situation. One apparently innocent American hiker is being released, as you know, while two others remain held, as, in effect, hostages. Have we now suffered 30 years of blowback for US imperialism during the Cold War?

President Jimmy Carter: Well, I wouldn't call it US imperialism. I think that these hostages, I don't call them hostages now. They're just prisoners who violated Iraq's sovereignty by crossing the border between Iraq and Iran, and they violated Iran's sovereignty inadvertently, they claim, and I go along with that. I just got back from North Korea, bringing out a prisoner who crossed the border from China, walked across a frozen river into North Korea, and was captured. We have to realize that those countries have very different frameworks of law and violation of their borders than we do. And my hope is obviously that we'll soon see the release of the other two American so called hikers who inadvertently crossed the Iranian border.

Brian Lehrer: On the big picture of 30 years now of these kinds of relations with Iran, and whether it's all their fault or whether we owe them an apology on some level for past history, what do you think?

President Jimmy Carter: I don't think we owe them any apology. They've abused us more than we have them. You have to remember that after the Shah left Iran and after the Ayatollah Khomeini's revolutionary government took over, we immediately restored diplomatic relations between our country and theirs. I was willing to get along well with them. In fact, that's why we had diplomats in Tehran, because we did have full diplomatic relations with the revolutionary government in Iran. My hope the last 30 years have been that we would reestablish diplomatic relations with Iran, have diplomats in Tehran, so there would always be a constant avenue of communication between the United States and Iran, no matter how much difference we had on, of opinion on different issues.

Brian Lehrer: Your diaries refer to the Afghan freedom fighters after the soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

President Jimmy Carter: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Some of these people would become the precursors to al Qaeda. Did you have any discussions at the time about the potential for an islamist oriented rebellion to turn against the United States, given what was happening in Iran?

President Jimmy Carter: No, I did not. We were deeply concerned about a threat to American security from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan because if they had been successful in Afghanistan, they could very well have moved into Pakistan and other adjacent countries and threatened all supplies of oil from that enormous region to the outside world. I was very stern about trying to restrain the Soviet advance. We gave secret help to the freedom fighters in Afghanistan who were ultimately successful in expelling the Soviet Union. I think the al Qaeda people were ones that came in from, actually from Saudi Arabia and Osama bin Laden, and they were welcomed into Afghanistan by some of the former freedom fighters. Most of the freedom fighters, obviously, have never been involved with al Qaeda, although a few of them have.

Brian Lehrer: After your recent trip to North Korea, which you mentioned a minute ago to bring home an American, you came home saying North Korea wants to make a deal on its nuclear program and a comprehensive peace with the United States. After decades of recalcitrance, why would North Korea want to make a deal now?

President Jimmy Carter: Well, they wanted to make a deal 16 years ago, and I went over there and we did work out a deal between me and the former leader of North Korea and Kim Il sung. Later, President Clinton adopted that agreement that I worked out. Then later on, under the six power talks, it was reconfirmed. Unfortunately, there haven't been any peace talks with North Korea now since 2009. There's no doubt in my mind that the North Koreans now want to have the same kind of peace deal that I worked out 16 years ago, but the United States won't talk to them. To repeat myself, the last effort we've made to even have direct talks with North Korea, even in the six-power framework, was now two years ago, almost two years ago.

Brian Lehrer: What do you think the US goal should be with respect to some of the world's worst human rights violators like North Korea? Should it be a normalization of relations or more pressure to see a regime like that fall?

President Jimmy Carter: I don't think the sanctions work. I think, in generic terms, sanctions against the people of a country like Cuba for now more than 50 years, or North Korea and so forth. I think they're counterproductive because they strengthen the regime with which we disagree. Now the Cuba dictators, Raul and Fidel Castro, can blame all of their economic problems on the American sanctions. The same thing is the case in North Korea, where the sanctions are preventing our working toward a goal that all of us want, that is a denuclearization of the entire Korean Peninsula and a peace agreement or peace treaty between or among the United States and North and South Korea to replace the temporary ceasefire, which legally means that we are still at war and just suffering under ceasefire. I think we ought to be much more accommodating, much more reaching out to find a common ground on which we can resolve these differences.

Brian Lehrer: President Carter, I know you have to go. Thank you so much for your time today.

President Jimmy Carter: I've enjoyed talking to you. You have some good questions, and you knew what you're talking about. It's a pleasure.

Brian Lehrer: Former President Jimmy Carter here on this show in September of 2010. Exactly 14 years ago, he was only 86 then. Then we replayed that interview as part of our series 100 years of 100 Things. It's thing number 25, 100 years of Jimmy Carter, who turns 100 years old himself tomorrow. We'll get reaction to that after a break with our guest still with us, Jonathan Alter, author of the biography called His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life which came out in 2020. We'll invite your reactions or comments or questions or how about your birthday greetings for Jimmy Carter as he turns 100 tomorrow? 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692 call or text.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC in our centennial series, 100 years of 100 Things. Today it's thing number 25, 100 years of Jimmy Carter, who himself turns 100 years old tomorrow. Still with us, Jonathan Alter, author of the biography called His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life which came out in 2020. Jonathan, 100 years of Jimmy Carter and 45 years now of Iran and the US considering each other an axis of evil, obviously, that's very much in the news right now. I'm curious about any top thoughts you were having as a biographer of Carter while listening to that tape.

Jonathan: Well, I agree with what you said earlier, that it is impressive that he even did that interview on that topic. It shows how Carter has always been willing to be held accountable and to acknowledge some of the less comfortable parts of his past. I mean, I think his rendition of events was accurate but incomplete. The reason that this so tarnished him is that it was different from the way he handled these major foreign policy accomplishments. Peace between Israel and Egypt at Camp David, the Panama Canal treaties which prevented a major war in Central America, normalization of relations with China, his human rights policy, which changed the world.

The reason this one was different was that on Iran, President Carter essentially tied his own hands. He told the families not long after the hostages were seized that he wouldn't take any action that might cause bloodshed. He gave away his leverage over the Ayatollah. His mother, Miss Lillian was saying, "Well, why can't you get a mafioso to go kill him?" Even his wife Rosalind wondered why he didn't bomb Iran. He had good reason not to do that, because, as he said, the hostages might well have been killed, but he could have acted with more boldness and surprised them, maybe by mining some harbors, just put the Ayatollah on edge.

Instead, he was essentially held hostage for those 444 days, and he let his presidency be held hostage. Having said that, Brian, he got them all home safely. Now, you mentioned that they didn't actually clear Iranian airspace, the released hostages, until right after, just moments after Ronald Reagan took the oath, but their release was negotiated all night by Jimmy Carter sleeping on the couch in the Oval Office and bringing them all home in one piece. It's a mixed legacy on Iran.

Brian Lehrer: I think Barbara in Bergen County wants to pick up right where your last answer right now just left off, and Barbara with some personal connection to that era with Carter and Iran. Barbara, you're on WNYC. Thank you so much for calling in.

Barbara: Hi, thank you. Good morning, and good morning for all of your dedication to this country, Mr. Bryan Lehrer. Happy birthday to President Carter. Possibly the best president that we've ever had, certainly in my lifetime. I became politically aware back in the Kennedy administration when I was in first grade because of his children, and I was living in Massachusetts. Jimmy Carter. I was on the flight line, I'm an air force veteran. I was actually on the flight line in Rheinmein, Germany, during the Iran hostage crisis. The hostages were returned. In fact, I had launched the backup airplane. The military always has a plan B, and my aircraft were the plan B.

The DC-9s, the Nightingales, were launched. I had very close connections with the Nightingale folks. We were all on the same flight line, but I launched and I left there in October of '81. I was on the flight line when the hostages were returned. I launched aircraft stuck around for them. They arrived probably about 7:00 or so in the morning. They closed down the air base. I couldn't have left if I wanted to, but I didn't want to. The timeline is a little uh, uh, uh. They were returned certainly before I left in October of '81. I will, however, say this, that once Ronald Reagan was elected, the exchange rate in Germany was a mark 69 fenning.

When Ronald Reagan Washington elected, it went up to 2 marks. And then when he took office, it went to about 2.25, interestingly enough. I do have to say that to the younger folks, I now find myself apologizing I'm sorry. If it were not for the Reagan years, where would we be with our ecosystem? Would we be in the climate crisis that we were? Because that started with Jimmy Carter, and then it all went away under Ronald Reagan. Another interesting thing that happened, during that timeframe of when the hostages were in Iran, I happened to run into a navy maintenance person, one of my counterparts at a military recreational area, probably Garmisch, Germany, that the military could go for R and R.

This one gentleman had been the crew chief for one of the helicopters. I said, "What happened?" He said that in the navy they are not allowed to leave their aircraft until they're mission ready. They thought, well, the only closest place that they would go was Iran. They got a little creative writing with the logs, the maintenance logs, and one morning came down and the helicopters were gone and said, oh, crap, we're in trouble. Anyways, whether that's true or not, [unintelligible 00:32:45] the situation. I will say one last connection, and that is the Camp David Accords.

My late former mother-in-law actually had designed the dress that Rose Carter wore on the Saturday night state dinner Camp David Accords. She was the first Asian American designer in New York, Myeong Cho. She was there before Vera Wang. The compliment was that she had purchased it, that it wasn't sent as a promotional piece. Somebody chose that dress for Rose Carter. Fabulous--

Brian Lehrer: She bought it. Barbara, I'm going to leave it there. Thank you for a wonderful call recounting your connection to some of that history we were discussing. Let me get one more in here, Jim in Piermont, you're on WNYC. Jim, I apologize. We have about 30 seconds for you.

Jim: No worries. I just wanted to say happy birthday to President Carter, former president Carter. I'm a conservative, but he was a good president. Happy birthday.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. That caller had also told our screener, I guess I didn't give him enough time to get to it, Jonathan, that he wishes as a conservative that we had Democratic presidents like Carter still. I wonder if he was referring to the part of the interview where Carter said, we have nothing to apologize to Iran for. They've been worse to us than we've been to them, and didn't accept the label of American imperialism for the Cold War era at all. Did that surprise you at all in the Carter interview?

Jonathan: No, he always stood up for the United States. I think he was lampooned by the right wing as something that he wasn't. The caller is right that he was, in many ways, a moderate president. He worked with Republicans on many pieces of legislation. Reagan gets credit for bringing inflation down, but it was Carter who appointed Paul Volcker to the Federal Reserve. He did a lot of deregulation, some of it with Ted Kennedy, actually, and some things that might be considered a little bit more conservative nowadays were part of the Carter record. I think the main thing really is the contrast to Donald Trump.

That's what I'm really thinking about on Carter's birthday, because Jimmy Carter is the un-Trump in every respect. When I would be in his library going over the documents, they brushed away the Trump toxins. The contrast just couldn't be starker. Trump is corrupt and chaotic and vulgar, and Carter is honest and disciplined and respectful. Trump is a physically big man, but he acts small. Carter is pretty short. He's a small man, but he acts big. He has done so much for the world, not just in his post presidency, but if you look at the policies that he got done, he was a political failure, but a substantive and often visionary success as president.

Brian Lehrer: Of course, his post presidency has been so much celebrated with Habitat for Humanity and his work on human rights. Of course, he's been controversial for calling Israel an apartheid state as early as 2007.

Jonathan: That's common. Now you hear Israeli politicians about making some of these apartheid comparisons.

Brian Lehrer: As he turns 100 tomorrow, he said he wants to make it to vote for Kamala Harris in the swing state of Georgia, his home state, of course, and we'll see if he does. I gather absentee ballots go out next week. Jonathan Alter, a biographer of Jimmy Carter, also has the forthcoming book, American Reckoning#; Inside Trump's trial - and My Own. This is an official on the air book interview invitation, Jonathan. Hope you'll come back. Thank you for doing this segment with us in our 100 years of 100 Things series, 100 years of Jimmy Carter, who turns 100 tomorrow.

Jonathan: Thanks, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.