Revisiting Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice: Don’t Look Back in Ardor

Rhiannon Giddens: Hey AriaCode Fans! We thought you'd enjoy this encore presentation of one of our favorite episodes from a past season. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode.

BARTON: I’m calling to her. I’m begging that they give me my love back. And I realize that that’s not going to happen.

GIDDENS: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

PATCHETT: We’re not gonna be able to go down to hell to rescue the ones that we love. And yet through those stories writ large, I think that in our small human ways, we’re able to deal with what life hands us.

GIDDENS: Every episode, we break down a single aria, so we can hear it in a whole new way. Today, it's “Che farò senza Euridice…” “What Will I Do Without Eurydice…” from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice.

WALTER: I think in the back of my mind, I kept waiting for her to get better. I kept thinking that the next tweak was gonna do the trick, and then we’d get back to the business of living our lives.

GIDDENS: Christoph Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice is based on the ancient Greek myth about a man named Orpheus who travels down to the underworld to bring his wife, Euridice, back from the dead. There’s this condition, though. There’s this pesky condition...

While they’re on their journey back up to the land of the living, he’s not allowed to turn back and look at Euridice -- he has to walk a few steps in front of her and trust that she’s still there. That’s hard for a man who loves his wife so much he’d follow her all the way down to hell. Well, he can’t resist, and the moment he turns toward her, she dies again. And this time, there’s no coming back.

It’s a story that’s been told a million ways -- in books, movies, plays, paintings… even video games. And there are a lot of different versions, as you might expect when stories get passed down. In Gluck’s version, Orpheus’s response to losing his wife for a second time is to sing this aria: “Che farò senza Euridice…” “What will I do without Eurydice?” It’s such a simple and beautiful expression of his grief. I want to take a closer look at that grief … and this music. And there are three people here to help me do it.

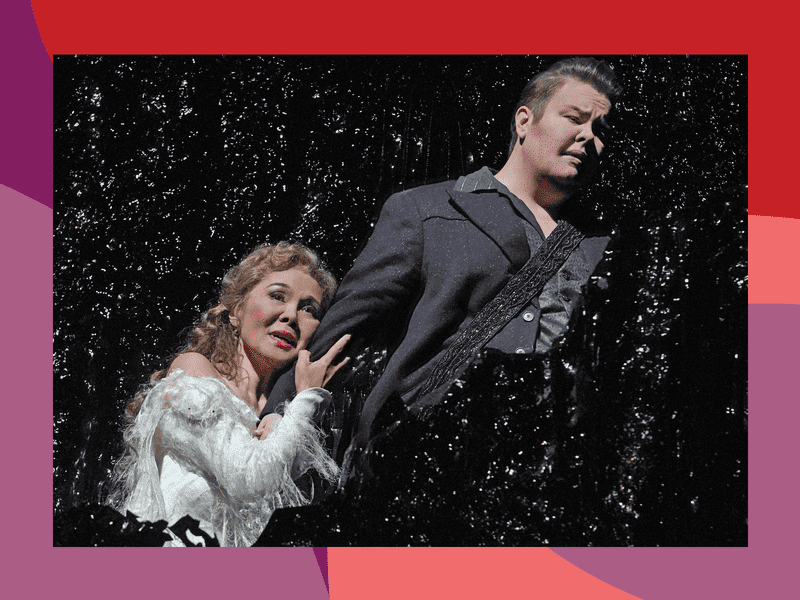

First, mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton, who sings the role of Orfeo. And yes, she’s a woman singing a man’s part… otherwise known as a pants role in the opera biz. But opera is not where her musical journey started…

BARTON: I grew up with parents that listened to a lot of classic rock. My dad literally would do kind of a music history quiz with me on the Beatles. Anytime they'd come on the radio, he'd say, “Hey Jamie, who's this?” and I’d name it. It was the Beatles. You know, “What album, what song?” You know, that sort of thing.

GIDDENS: Now that’s my kind of family! Next up, novelist and bookstore owner Ann Patchett.

PATCHETT: I knew nothing about opera until I wrote, Bel Canto, about the true story of the takeover of the Japanese embassy in Lima, Peru. I decided that there was going to be an opera singer among the hostages. And I really was like one of those annoying midlife converts where I just wanted to corner people at cocktail parties and talk to them about my new found love of opera.

GIDDENS: Welcome aboard, Ann! And finally, Jim Walter. He lost his wife, Leslie, back in 2015.

WALTER: The feeling of losing her hasn't changed. It's just hazier than it was then when it was bright and hot and painful.

GIDDENS: Grief is such a complicated experience. There’s no set path when you’re coming to terms with loss, and living through the pain of it is different for everybody. Today’s aria is all about that pain, and the desire to bring back the person you loved. Let’s get into it. “Che farò senza Euridice” from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice.

PATCHETT: When I was in graduate school at the Iowa writers workshop, they had a great foreign film series. And I used to go with my roommate and best friend, Lucy Greeley, who was a poet. And we went to see Cocteau's Orpheus. And then in 2002, Lucy died. We were both 39 years old. And I remember the day after she died, all I wanted was to see that movie again. All I wanted was to believe for a minute that this could be true, that she could have gone some place from which I could have rescued her.

PATCHETT: In the Orpheus myth, Orpheus has lost his wife, Euridice.

BARTON: His wife -- or wife to be, I should say -- on the day of their wedding was bitten by a snake and died. And so this wedding turns into a funeral. And you see this story unfold of him just barely believing that he's lost his love.

WALTER: I was 29, I think when I asked her to marry me. We had Emma in 2002, and three years later, Lily was born. I lost the ability to imagine myself living without her. She was all the things that I wasn't, in both good and bad ways. She was more organized than I was. She had a great moral compass. We were a fitted pair, and by virtue of our time together, we both sort of became better people for it.

PATCHETT: Orpheus plays the lyre, and he has a beautiful voice.

BARTON: He was known in all of the iterations of the tale of Orfeo -- or Orpheus -- as maybe the most talented musician on earth at that time.

PATCHETT: Music is always what breaks the heart of the gods and moves them to mercy.

BARTON: In his moment of grief and anger, the gods hear him…

PATCHETT: And he is so bereft that the gods take pity on him and they allow him to go to the underworld to bring her back.

BARTON: Amore, Love, the God of love, comes down and tells him this and says, you know, “You get to do this, but the stipulation is that you're not allowed to look at her, and you're not allowed to tell her what's up.”

PATCHETT: And he can lead her back to life while all of the Furies are torturing him and mocking him and making his path difficult.

BARTON: He decides to take on the challenge, of course. And so he goes through hell, literally... battles the Furies with his music.

WALTER: In 2008, we had come home from a party, and she found a lump in her breast, and she... she asked me to check it out, and I did and I didn't know what it was. And so of course she was worried, I was worried. And we set up an appointment at the hospital, and it turned out it was a tumor that they said could have been growing inside her for as many as seven years. It was very slow growing at the time.

PATCHETT: So here's Orfeo, he has suffered the slings and arrows of all of the Furies on his journey down. He's basically in hell. He wants to get his wife, and he wants to get the hell out of hell. He's leading her up this rocky cliff, and she basically is just carping at him from behind him the whole time saying, “Do you not think I'm beautiful anymore. The roses in my cheeks, have they faded? Are my eyes not as bright? You just don't really love me. You don't care for me,” as he is trying to restore her to life.

BARTON: In my mind, she's feeling the effects of a panic attack. Her heart is racing. She can't breathe. She's trembling; She feels like she's dying and I can't embrace her.

PATCHETT: His heart is breaking. He wants to comfort her; there are all of these asides: Oh, oh, how can I bear this? How can I stand this pain of her suffering?

BARTON: I can't hold myself back any longer and my reason is abandoning me, and I can't resist. And I turn around, and I say, “Oh my treasure.”

PATCHETT: And by turning around, he's broken the deal with the gods.

BARTON: And then she dies. The music stops. We watch her float away. And I have this massive pause where there's just silence. And then I come back in, and I say, “What did I do?” And the sense of utter loss is just overwhelming.

PATCHETT: He has lost her for a second time. It's really as bad as it gets. And that's how he arrives at this aria in which he is singing, “How can I possibly go on without my wonderful one?” There's nothing for me either in this world or the next world.

WALTER: After the first diagnosis and the initial shock wore off, we were relatively upbeat about it. We were seeing good results, tumor was shrinking, and our take on it was -- the cancer comes in, we treat the cancer, we slog through the recovery period, and then we get on with our lives. And if cancer rears its ugly head again, we just get treatment again and just do the same thing over again. We had sort of made our peace with it. There was a turning point maybe two years after that. The cancer had had migrated to her lung, and her lung had begun filling with fluid. I probably was living in a little bit of denial for a very long time. I think in the back of my mind, I kept waiting for her to get better. I kept thinking that the next tweak was gonna do the trick, and then we’d get back to the business of living our lives.

BARTON: So when listening to “Che farò,” you'll notice from the very first moment that it's in a major key, so it kind of sounds a little happy. And I think that that's actually a really interesting bit of storytelling. What he's saying is, “What will I do without Euridice?” “Dove andro senza il mio ben…” “Where shall I go without my beloved?” What am I going to do? Where am I going to go? Those are the two things that he is most concerned with, and I think that's why we get this kind of simple sound to this aria.

PATCHETT: This aria has very, very few words in it. It's repetitive because there really is nothing else to say when you're talking about the death of someone you love. It is just, “This can't be true. I want her back. I love her. Give her back to me.” There isn't anything else. It is all about the act of repetition. Please, please, please, not this, not this.

BARTON: With normal vocalization, it’s very natural for the voice to have vibrato. That is naturally what the voice does. When somebody takes that vibrato out intentionally, it helps call attention to whatever is happening, I think, it just brings the listener’s ear into it. In “Che farò,” for instance, he's saying her name, “Euridice, Euridice.” And then he says, “Rispondi,” please answer me. And I have a very long “rispondi.” So, I just decided to do a very clean, straight tone sort of thing. And I think that it really helps the listener hear that this is a special thing. This is something that is different from what you're hearing around you.

WALTER: Ultimately, her breathing became more labored, and she moved to a portable oxygen tank. From that to oxygen drums, like these massive cylinders that were in our bedroom. And, and we had cannulas snaked around the house because she couldn't walk up or down the stairs without the benefit of oxygen. The cannula sometimes would come off in her sleep. She would knock it askew. And at that point, she was gasping for breath. She was sipping at air. She couldn't get enough oxygen to fill her lungs. And it was the middle of the night, it was like two or three in the morning, and she was yelling at me, and I couldn't figure out what was going on and I turned on the light and I, I finally realized the cannula had fallen down and I, I tried to put it back in her nose, and she kept knocking my hand away because I was putting it in upside down, but I didn't realize it. She kept knocking it out of my hand, and at this point, I am, I am panic-stricken if I don't get this cannula back in her nose, she's dying in front of my eyes. I got the cannula back in her nose, it was right side up, she was breathing again, and I just, I just collapsed on her bed, like I just didn't know what to do with myself. I just… I couldn’t cope.

I've never felt that level of anxiety, stress, panic. Anytime I would fall asleep; I would panic awake.

BARTON: Then we get a return of “Che farò,” this, “What am I going to do without her? Where am I going to go?” Followed by a little pause, where then I say “Euridice,” I call to her again. And then we start this really beautiful Adagio. You can hear the music shift into a minor key, and it really slows down. I always think of it as if the heartbeat has slowed down a little bit. He's had his panic, and now he is feeling reality setting in. He's never going to be able to call to her and get her back. He is literally stuck in this in-between-worlds place, and you hear this dread in this minor key.

WALTER: It was at that time that the physician's assistant had pulled me aside and said, “Has anyone talked to you about Leslie's breathing?” And I'm like, “Well, you know, obviously everyone's talked to me about Leslie's breathing because she's, you know, struggling.” And she said, “um, when someone is near death, they exhale, and there's almost like a hitch in their breath before their system kicks back in and then they, and they breathe again.” And she said “This is typically seen in people who only have a very short time to live.” And I was floored. I just, I didn't even know what to do with that. I went back into the room; I asked Leslie if she wanted to know what they had told me. She said she did. And I, I told her, I said, that they think that you're dying, they don't think that they can, that they can save you from the cancer. She said, “how long?” And I said that they didn't know that it could be any time. Um, she said, “I just want to see Emma get married.” And I just shook my head. And she said, “then I want to see her graduate.” And, um, and I shook my head again and, uh, and we just cried.

PATCHETT: What happens is our experiences bury over time, and then things grow out of them. It's like composting. You just dump everything in your life -- every conversation, every book you read, every movie you see, everyone you love, everything you do goes into the compost of human existence. And then things grow up out of that. And so years later, when I was writing State of Wonder, and it was so connected to the Orpheus myth, I wasn't thinking, I'm gonna sit down and write a book about Lucy. It had been, by that point, many years since she had died. And it wasn't until I finished the book and I read it that I realized what I had done, which is to bring back the person who was lost. And and the wonderful thing about writing a novel is that you get to control that. And say, “You are gone, you're dead, I'm going to bring you back.”

WALTER: I tell people about this short story called “The Stopwatch,” where a man makes a deal with a devil, and the the devil tells him he can pull the stopwatch at any moment in time, and then that time will be his forever. He can replay that moment forever. And the man can't make a decision about where to pull the stopwatch because he keeps waiting for the next good thing until, at the end of the story, he ends up surrendering the stopwatch to the devil, or almost does. But I remember the last day with Leslie with all her friends and family around her was just a really good day. She had that... that bounce back that people talk about before they die. And then, she fell asleep, and her sister stayed with her. Emma and I took a break. We were going into a little relaxation area. We were working on a jigsaw puzzle together. And, um, the nurse came in and said, “I think you need to come to the room right away. Um, she's, she's passing.” So we sprinted down the hall and, and, um, she was, she was still with us. We all just, uh... it was like a full-court press trying to get as much love communicated to her as possible, uh, from as many people as, as possible, uh, all of us, um, you know, telling her it was okay, that we had it under control, that we love her, that we were missing her. Um, and, and then ultimately she did pass and, and the nurse, uh, took her vitals and confirmed it, and, and, uh, and she was gone.

PATCHETT: Grief is such a pure and simple emotion at all range. It can be very loud. It can be very quiet. It's sleeping; it's waking, it's dreaming, it's living. It's so all-encompassing, especially in those first hours, weeks, months, years of loss. You want to find another way to say it, and yet there really is no other way to say it. I want this person back.

BARTON: We return back to “Che farò,” the last return of this main section and the way I like to do it is to really take it down to a pianissimo, this kind of lost little boy space, because there is a vulnerability that happens when a singer does that. It's not very often that I think these stories really show the vulnerable side of the heroes who are involved. It's a beautiful way to end out this aria.

PATCHETT: The myth of Orpheus is a tragedy, and yet this opera is not tragic. At the last minute, the gods come down and say, “Okay. All right. We didn't really mean it. Here she is.” She wakes up again, and he gets another chance. And then we get this resplendent close at the end of the opera.

BARTON: I really think ultimately Orfeo is about the power of love, quite literally the power of the God of Love, but also the power of love when it comes to Orfeo and his grief. You really get the sense that Orfeo is completely lost without her. And so I think that the power of love in this is what brings her back.

WALTER: Every so often, I still get a gut punch. I remember I was buying groceries, and I happened to push the cart past the tomato sauce. And it just came to me like a thunderbolt. I don't know how to make Lesley’s spaghetti sauce. She'd never wrote down the recipe. She always just sort of threw in a little of this and a little of that. And the kids loved it, and we ate it all the time. And it was just gone. Just like Leslie was gone. This, this stupid tomato sauce, and there were a lot of little things like that. Things that I wouldn't have thought would have bothered me. Man, they'll bring me to tears, like nothing, but I can't do anything about it. And so anytime I find myself dwelling on those things, I immediately switch gears to, what are all the things that we were able to experience before she did pass away. There were so many things, so many great experiences.

PATCHETT: I think about how the Orpheus myth has shaped my life and how it's shaped how I think about death. Someone's gone, you can get them back if you just love them enough. You can get them back. And I look at my husband, and he's 16 years older than I am. We've been together for 25 years. I love him so much. And I always think, “If anything ever happened to you, I would go and get you. I would go and get you. You could come back. Don't worry. I would; I would bring you back.”

END OF DECODE

GIDDENS: That was mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton, novelist Ann Patchett, and writer-blogger Jim Walter talking about “Che farò senza Euridice” from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice. Jamie will be back to sing the whole thing right after the break.

[Break]

GIDDENS: Here’s mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton singing “Che farò senza Euridice” onstage at the Metropolitan Opera.

[Jamie Barton sings “Che farò senza Euridice”]

GIDDENS: It’s time to wrap up this episode of Aria Code. If you’re enjoying the show, tell a friend to listen. Tell all your friends to listen. And leave a review in Apple podcasts... it really helps us out.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.