Davis’s X: The Life and Legacy of Malcolm X

Zaheer Ali: The Nation of Islam had a whole black world where black people were the center, not the margins, where they were the subjective creators, not the objectified people.

Rhiannon Giddens: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

Anthony Davis: The aria kind of captures the relationship of our community to the police, to the power structure, and realize the pain that comes out of that.

Rhiannon Giddens: Every episode, we look at a single aria from every angle, so that we can understand it more fully. Today, it's “You Want the Story, But You Don't Want to Know,” from Anthony Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X.

LIVERMAN: And that's kind of where we find him as this man who's been nearly broken by society in every way, even from him when he was little, because of a system that failed them and they were never set up to win.

Rhiannon Giddens: What's the image that comes to mind for you when you think of Malcolm X? Is it the icon of the civil rights movement in America, or a young man thrown in jail for burglary? Is it a believer who made a peaceful pilgrimage to Mecca, or someone who sparked controversy across racial and religious divides? Is it the fearless speaker who inspired a generation or a man whose assassination sent shockwaves through the movement?

For me, it's all of these things. Malcolm X was a multi-layered person who had an incredible journey of self-realization and an enormous impact on the world around him in his short lifetime.

But with a figure this famous and this incendiary, it can be difficult to see his humanity and to understand both his life and his legacy. Today, we're going to look at his story through the lens of X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X.

The opera was composed by Anthony Davis, his first, with a libretto by his cousin, Thulani Davis, and based on a story by his brother, Christopher Davis.

It had its premiere at New York City Opera in 1986, and it was groundbreaking for several reasons. Not only is the score full of jazz, blues, and swing influences, it also takes an unflinching look at racism in America.

Malcolm sings his Act 1 aria, “You Want the Story, but You Don't Want to Know,” in a prison after being arrested for burglary. It's a moment of dramatic transformation for Malcolm, and righteous indignation about racial injustice.

Although the aria comes out of real life events that took place in the mid 1940s, the unfortunate truth is that every single word could just as easily apply to our world today.

Nearly four decades after its premiere, Anthony Davis's opera has as many things to teach us about Malcolm X – and America – as it ever did. And we have three guests to tell us why.

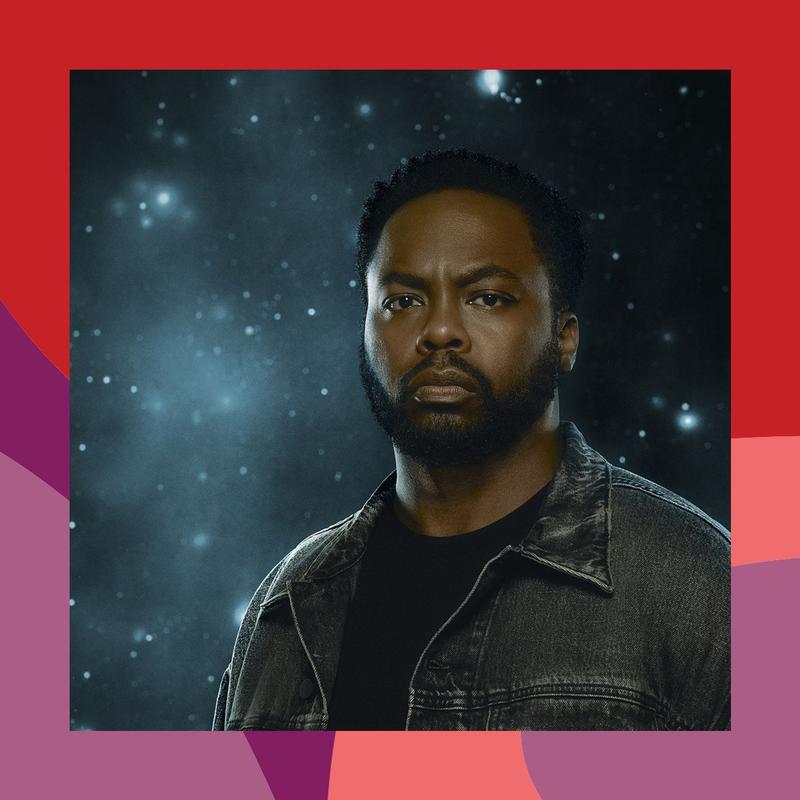

First, baritone Will Liverman, who ran the full gamut of emotions when he first learned he'd be singing the role of Malcolm X at the Met.

LIVERMAN: It was a feeling of excitement, of course, to be able to step into this role in a city where he meant so much. But right after that is, you know, to be honest, fear. How can I step into this man's shoes and do this story justice?

Rhiannon Giddens: Next, the man who brought Malcolm X to the opera stage, Anthony Davis. Anthony is proof that music really can be someone's native language.

Anthony Davis: People tell me that the first time I played the piano, I was sitting in the jazz pianist Billy Taylor's lap, who lived in our building in Harlem, and we played four hands, and I was… literally Billy Taylor told me that I was in diapers, so… [laughter]

Rhiannon Giddens: And finally, Zaheer Ali, Executive Director of the Hutchins Institute for Social Justice at the Lawrenceville School. In the early 2000s, he was the project manager of the Malcolm X Project at Columbia University. But Zaheer's interest in Malcolm was awakened decades earlier.

Zaheer Ali: As a Muslim growing up, I had known about Malcolm X, but not really more than just the name. And as an 11th grader, my English teacher assigned the autobiography of Malcolm X. And it had this explanatory power that gave meaning to how I was understanding race in America. So, it almost became a kind of scripture for me.

GIDDENS: We're ready to take a closer look at this icon of the Civil Rights Movement.

Here's You Want the Story But You Don't Want to Know from Anthony Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X.

DECODE

Anthony Davis: X opened at New York City Opera in 1986. There were lines of people around the corner, and they were bussing people from Harlem, which was amazing to me. Also, to be at Lincoln Center with a house that was 50 percent African American and was sold out.

It was very exciting to me to try to do something that spoke about who we are as a people and what our aspirations are.

LIVERMAN: My dad was a history teacher, so, you know, every time when Black History Month would roll along, we'd be busting out all the posters and things of Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and… and every year, as you know, I got older, we would revisit these stories, and Malcolm X was always at the forefront.

Zaheer Ali: Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska on May 19th, 1925. His family moved to Lansing, Michigan, which is where he spent his early childhood. His parents were very active in Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, which was a black mass movement founded by Garvey in 1917, and had grown to become the largest Black mass movement known in American history at that time.

It was a movement that adhered to the principles of Black nationalism, advocating for independent Black institutions in education, in economics, in politics, in culture, and is often called a Back to Africa movement. And so Malcolm was born into a family that was part of a movement that advocated for Black autonomy, Black dignity, and personhood.

His father, Earl Little, was an organizer in the movement, and his mother, Louise Little, was a writer for Garvey's newspaper, The Negro World. So they weren't just members. They were active organizers in that movement.

Anthony Davis: Well, the opera begins in Lansing, Michigan in a Garvey meeting at Malcolm's house, and Malcolm is a child.

Earl hasn't come home yet. And Louise worries about her husband and recalls other tragedies.

Zaheer Ali: One of Malcolm's earliest memories is remembering his family being attacked by members of the Black Legion, which was a kind of Northern version of the Klan. They firebombed his house. And so he remembers as a child his family being targeted by racist violence.

And the attacks on Malcolm's family would continue as his parents continued organizing black communities. And in 1931, Earl Little, Malcolm's father, was killed.

Anthony Davis: He'd been pushed on the train tracks by the Ku Klux Klan.

Zaheer Ali: Louise struggled to hold the family together, and eventually the state intervened and had Louise institutionalized. And the children split up as wards of the state and Malcolm was sent to a foster home.

Anthony Davis: I think of Malcolm being haunted by this violence. The violence that killed his father and haunted his family. And then the violence eventually took him.

LIVERMAN: We don't want to face the monstrosities of our American history. I think about my dad, and we're having to talk about Malcolm X, and he was telling me about growing up in Virginia, you know, where I grew up, and how you couldn't go to certain places of Virginia at night because the Klan would be out, and how bitter the water tasted from the Colored Fountain. I'm hearing this from my father, you know, like, and that was just also another impactful moment for me, just thinking about our realities in this country. It's just... The plain, cold, hard facts.

Zaheer Ali: The foster family that Malcolm was sent to live with was a white foster family, and during that time, he was sent to a predominantly white school. He was popular, and was even elected class president, and excelled as a student. So much so that he shared the dreams that his classmates had for their own futures of growing up to be a lawyer or a doctor, a professional. And one of his teachers discouraged him as having unrealistic dreams for a quote-unquote Negro child. He began to understand that the prospects for him as a black child growing up in America were going to be very different than that of his white classmates.

He began to struggle with delinquency.

Anthony Davis: Malcolm is kind of lost as a figure, and, uh, he sings his first aria as a child.

LIVERMAN: Ever since he was a kid, you know, he had such a turbulent life, and all those experiences made him the man that we know. I, uh, read his autobiography, which was so powerful and eye-opening.

I've watched the famous Spike Lee movie as a source of inspiration. I, you know, wanted to get as much information and understanding his journey myself. Knowing that I can't ever possibly step into this man's shoes and like pretend I'm walking around on the Met stage as Malcolm X. It's really more of an embodiment of his character.

Zaheer Ali: As Malcolm struggled as a teenager, his half-sister, Ella Collins, who lived in Boston, came to visit him. I think he was about 15 at the time. And she saw Malcolm drifting and invited him to stay with her in Boston. And it is in Boston that he's introduced to a black urbanity that he had not yet experienced.

Anthony Davis: He's then introduced to Street, who brings the street life to Malcolm. Street is a combination of many people in the autobiography.

So Malcolm's transformed. He, too, is now a hustler.

Zaheer Ali: And participating in what we would call the underground economy of drugs and prostitution.

Anthony Davis: Street’s telling him how to be a pimp, how to be a drug dealer, how to take people's money. Also, in a weird way, how to be a man in a street context.

Zaheer Ali: And also, this was his first encounter with the culture of swing and jazz and the zoot suits that the swingers would wear. Baggy pants, long jackets, there was a hat that went with it. In wearing a zoot suit, you were declaring your non-allegiance to the war effort because of the cotton that was needed to make the zoot suit and was being rationed. So, this was a political statement as much as it was a cultural one.

Anthony Davis: Street speaks in a way that other people don't, saying a kind of a truth about these middle-class aspirations and the kind of hopelessness of it.

Zaheer Ali: It was a defiance of ideas of respectability, of middle-class norms. It was a defiance against institutional injustice. It is a defiance in support of cultural self-determination. And really a thumbing of the nose at notions of respectability that had rendered working and lower class Black people outside of the framework of justice and equity.

Anthony Davis: What Street presents, and the seductiveness of that, is the freedom he offers, the idea of not accepting the limited options that a young African American faces is something that I wanted to really explore, but also to make that music fun. And I wanted to have the music create the time and the place you're dealing with, the late 1940s Malcolm's working the dance halls in Boston. So it's all using the blues in different ways. You know, the swing that you hear is part of Malcolm's seduction. Street is seducing Malcolm into the life.

Also, in a sense, I want the feeling that the audience was seduced, too. Say, oh, well, that's an alternative. I could go outside the system, go completely rogue.

Zaheer Ali: Malcolm, as a light-skinned, or some people would say red-boned, young man, got the nickname Detroit Red. And as Detroit Red, he became fairly prominent. He was a charmer. He measured his social capital by how many women he could have in his orbit. And he also was a drug user, and then had to feed a habit. In order to pay for this lifestyle, he and his peers began scheming and engaging in crime.

He had a crew. And they organized a heist with the help of two white women. These women had helped Malcolm identify a home of someone who would not be there and they went and burglared the home. And that landed Malcolm in prison.

LIVERMAN: And that's kind of where we find him as this man who's been nearly broken by society in every way. Even from him when he was little. You know, his father getting torn in two by the Klan. You know, his mother going mad. Because of a system that failed them and they were never set up to win.

Anthony Davis: In prison, he's being interrogated by the police. And the idea in the aria was that you don't hear the questions. And then Malcolm's answers are not what the police would expect. So in this interrogation, as the light shines on him, he kind of recounts his own story.

And what's introduced is this B, C-sharp pedal. Those notes would be very dissonant if you put them in a different register, but spreading them apart emphasizes that you're hearing two tonalities together. I wanted to create this profound emptiness. It's the bottom of the orchestra and the top of the orchestra, and it leaves the middle for the improvisation.

It leaves the clarinet to explore with the bowed vibraphone. A vibraphone is a metal keyboard instrument. Then using a bow, a violin bow, you can create this very sustained, interesting texture. So it's something that creates kind of the aura around what the clarinet's doing. And the clarinet is playing around with multiphonics.

Multiphonics is when you can play more than one note on the clarinet at a time. By doing different fingerings and how you use the embouchure, et cetera, you can create different kinds of multiphonics.

Zaheer Ali: While Malcolm was in prison is when he undergoes another significant transformation in his outlook. It started with his siblings writing him about the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, and There is a lot about the Nation of Islam that is a continuation of Marcus Garvey's Black Nationalism.

And Malcolm grows increasingly interested. He joins a debate team. He's reading voraciously. and begins asking the prison authorities for dietary accommodations so that he isn't served pork. He begins advocating for space for prayer that faces east. So, while Malcolm is incarcerated, he begins his activism as a Muslim.

Anthony Davis: Then you hear this kind of rumbling, and then, uh, you hear the 5/8 figure. I like to emphasize different parts of a rhythmic figure so that it changes color. You hear different kind of other rhythmic patterns as you play it. It creates a kind of rhythmic momentum, but there's a tension behind it.

Zaheer Ali: The Nation of Islam had a whole black world where black people were the center, not the margins, where they were the subjective creators, not the objectified people. This opened up Malcolm's thinking even more about the possibilities. For himself and his community.

Anthony Davis: And then … with the horns and the brass.

LIVERMAN: I wouldn't tell you what I know, you wouldn't hear my truth. It's a slower tempo, a grounded and steady 4/4. You want the story but you don't want to know. You really get every single word because that rhythm is the foundation. As a performer, all the storytelling that we do, the music is the foundation for that.

The space in the music is just as important as when we're singing. The space to live in the energy of what we just said, so people really get it.

Anthony Davis: You had your foot on me always pressing. And you think of George Floyd and what happened in Minneapolis. The aria kind of captures the relationship of our community to the police, to the power structure, and the pain that comes out of that.

My truth is, white men killed my old man, drove my mother mad. Here we have big intervals with a voice, bringing in the tension – his visceral, emotional quality into the vocal line as well.

Zaheer Ali: Malcolm was paroled in 1952 after serving six years. And he committed himself to spreading the message of the Nation of Islam to as many people as possible.

He also was invited by Elijah Muhammad to spend time with him, and Elijah Muhammad becomes a kind of father figure. And so he quickly grew in stature in the Nation of Islam as its chief organizer and eventually its national spokesperson and had received the assignment of setting up temples around the country.

Here is a Black organization that is willing to give, in the language of that time, an ex-con, with no, like, high school degree, no experience as an organizer – the keys. Here's the keys, here's a microphone. Go organize people. Malcolm had these traits as a child, which is why he was elected president of his white class.

That was something that was covered up with the dismantling of his family. It was covered up. by the teacher discouraging him. It was covered up by the socioeconomic conditions of being a young black man in that time period. It was covered up by prison, but Elijah Muhammad was able to see through all of that.

And in that opportunity, he shines. He exponentially increases the membership of the Nation of Islam. He emerges as skilled in messaging, in public relations, in media management, in communications. He's very skilled.

LIVERMAN: And then things change a little bit when Malcolm X gets to, “My truth is rough, my truth could kill, my truth is fury.” Like, you guys aren't ready for my truths. And with that, we get a change in the time signature to an irregular meter that oftentimes us singers don't really see as much. A 5/8 irregular meter, and it starts to get a little complex, and I think that represents all the things, you know, probably going on through Malcolm's mind, and just all of the things that he's reliving. It's a very complex and hard life, and maybe that's why the rhythms are hard too.

Anthony Davis: When I was composing it, I felt a strong identification with Malcolm myself. How he came through all these obstacles to find his true self. I identified with Malcolm's rage. As an African-American artist in the 80s fighting against systemic racism that existed in the art world. If you look at classical music in the 80s, there's the uptown scene in New York and the downtown scene.

And both scenes excluded black people. It was not, they're not very welcoming to any person of color. We were no town rather than uptown or downtown.

So, uh, that rage sort of fed me. And I, I think the words that Thulani wrote in the aria really kind of captured it in a universal way.

LIVERMAN: Thinking about my own experience as a Black man in America, and, you know, we have to deliver the story, but there's a deep emotional attachment to this that I will have to find a way to navigate through.

It might bring me to tears because of, you know, I just, I feel that, you know, and it's… you gotta work through those things so you can find the balance in between when you get to the stage and have to tell this story, but there's so many deep connection points.

Zaheer Ali: The core of Malcolm's message was Black self-determination, Black self love, the need for Black people to create, build, and sustain their own institutions because they could not depend or trust white people to do justice by them.

For Black people who had experienced the impact of white supremacy, had experienced racism, they're like, Oh, that, there you go, that's pretty much, that's kind of what we thought, too. Somebody's saying out loud what we think quietly.

Anthony Davis: And then it goes back into the 5/8 section where it becomes more intense.

So there's a rhythmic underpinning that goes on in the music that drives the action, drives the drama, the relentlessness of it. And it's transforming and changing too as it goes along. I think one of the things as a composer you work with is how you deal with repeating material, but then also how you keep interest.

It's called changing same. Changing same. You have something that's similar, but then there's something that's transformed about it. It's not static. It's moving you from one thing to another. That's where the subliminal idea comes in. You plant the seed of the, a memory of something. And that, Memory will deepen the experience later.

Sometimes you can accuse me of being manipulative because I do that a lot. But I like the idea of music conveying emotion. And one of the ways is to have material that evolves, that, that comes back, that has a relationship.

Zaheer Ali: There was a gap growing between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad in the Nation of Islam because of political differences in how to respond to the civil rights movement.

and the growing demand by Black people for action. It was a gap that was growing due to personal differences, Malcolm's growing doubts about Elijah Muhammad's leadership and moral standing when Malcolm learned of Elijah Muhammad having fathered children outside of his marriage. There were spiritual differences.And there were organizational differences in terms of Malcolm's growing prominence within the movement, but not being a family member of Elijah Muhammad and many of those family members feeling that Malcolm was undeserving of the attention that he was receiving from Elijah Muhammad.

So there were a lot of factors that led to Malcolm's growing estrangement from the Nation of Islam.

LIVERMAN: There's lots of uses of triplets throughout the whole score. Singing a triplet is just like, kind of almost an emphatic thing to like, Bah, Gah, Gah… like, there's just something that just drives a point home. It brings out the words in a different way.

Those triplets in the 5/8 were murder for me, you know, like, I nearly had a heart attack at first. ‘Cause it is overwhelming, you know, it's not easy. It takes you back to aural skills. Tah-and-clap, you know, like you gotta really have your chops and it takes some time to, like, really sit with these rhythms and just speak them out. I don't even put the notes with it. Just speak it out first.

But then the rewarding thing is, when you start to get a sense of these rhythms, and how they're sung, how they're lived, it makes so much sense. And it really works.

This piece forces you to be, you know, in touch at all times. Nothing ever lets up. Malcolm's constantly on the move. The music represents that. And the freedom in the music, and the different styles that he brings in represents the freedom that Malcolm, you know, was fighting for.

Anthony Davis: When I started creating the melodic ideas, I was really into the sound of the words and the rhythm of the words. “I shined your shoes. I sold your dope, hauled your bootleg, played with hustler’s hope.”

I thought of how Malcolm spoke. He was percussive, his humor, his sense of space and timing. I wanted to capture that energy – how Malcolm could galvanize an audience and galvanize a community.

LIVERMAN: I mean, when Malcolm X spoke, I mean, you look, people listen. He was someone that just held that space, and when he delivers something, you gotta sit with that ‘cause he was so well spoken, and was just always had a way to just pinpoint the issue and speak on it. And here you have so many truths that people didn't know how to deal with it.

Zaheer Ali: In March of 1964, Malcolm announced that he was leaving the Nation of Islam.

Anthony Davis:He rejects Elijah Muhammad, and finds his own voice, and embraces Orthodox Islam.

Zaheer Ali: And then that break became increasingly personal and bitter as he criticized openly what he thought were the moral failings of Elijah Muhammad.

I call Malcolm's break from the Nation of Islam really a shattering because he left the Nation of Islam with pieces of the Nation of Islam in him and ideas and its legacy.

And he also left with his own legacy as someone who had helped build that organization and shape its culture. And so even though they were estranged from each other and this grew increasingly bitter, they were somehow inseparable.

Anthony Davis: It kind of accelerates and, dong, ding, ding. My truth is a hammer coming from the back. It will beat you down when you least expect.

LIVERMAN: Seems like every time he mentions truth, we get the meter change back to that steady 4/4 like, this is the foundation, a foundation of truth. But you guys don't want to hear my truth. You want your version of the truth, or the truth that makes you feel comfortable.

We go back to, “You want the truth, but you don't want to know.”

You get a sense of his motives to pinpoint the problems in our society. We don't have a foundation of truth to actually see one another and change. That's the only way we have to reconcile. But we don't want to look at the history. But the truth is the truth. And if we can't stand on that, how can we move forward as a country, as a world?

Anthony Davis: It comes back with that A and the E. The A, you hear with the trombone. Then the soft E with the piano, even after all the rage, it's the emptiness that he actually feels inside, too.

Zaheer Ali: By February of 1965, it's clear that Malcolm's life is under threat. The early morning of February 14th, his house is firebombed, eerily reminiscent of the firebombing of his house as a child.

He, at the time, felt it was the Nation of Islam that was responsible. And said that he had been having a series of meetings and on February 21st, there was a meeting taking place at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, we will now call Washington Heights. And at that meeting, there were men who got in with weapons, five or six people.

Two of them caused a diversion and left him exposed. He was an open target for a shotgun assassin, and so he was killed. In front of his wife and children.

LIVERMAN: We think of Malcolm X and he can strike a lot of chords with a lot of different people. We think about, you know, him as a controversial figure and people think about him as some angry militant leader who is, you know, inciting violence, but we don't think about his full journey. My hope is that we're telling this story to kind of kill these preconceived notions about who Malcolm X was and to find the humanity in him.

This man was brave enough to continue to change his mind. He stood firmly in the things that he believed in, but when he was wrong, he admitted that. And that's like one of the most human things that you could do.

Zaheer Ali: He was very much framed as someone who taught hatred, who preached the hate of white people.

But I think Malcolm's legacy is one of radical love. Love of Black people, love of liberation, of justice, love of humanity, and love of oneself, and the kind of love... that is so deep that self-critical engagement is possible. I do think that part of Malcolm's legacy is how much he has been able to shape our culture long after his death, that he continues to live on through the reimaginings that we see in our culture.

Anthony Davis: Our culture is under assault. African-American history itself is under assault. There's a segment of our society that wants to render us invisible, so we have to go back to Malcolm and think about how we can be part of a resistance. I think an artist can't be on the sideline now.

Music has a message. Music can transform. Music can make people feel and empathize and understand. We have to do everything that we can to be visible and to make works that speak to our history and also point to the future.

Rhiannon Giddens: Composer Anthony Davis, educator Zaheer Ali, and baritone Will Liverman decoding “You Want the Story But You Don't Want to Know” from Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X.

Will's coming back to sing it for you after the break.

MIDROLL

Rhiannon Giddens: Malcolm has just been arrested for burglary. He sits in a Boston prison, facing his interrogators with the truth that they refuse to hear. That racial injustice in America is the real crime. Here's Will Liverman singing, “You want the story, but you don't want to know” on stage at the Metropolitan Opera.

ARIA

Rhiannon Giddens: That was baritone Will Liverman singing Malcolm X's devastating Act I aria, “You want the story, but you don't want to know” from Anthony Davis's opera, X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X. That's a wrap for this episode of AriaCode. As always, we'd love to hear how you're enjoying the show, so please go ahead and leave us a rating or review.

Next time, we're taking a trip deep into the jungle.

PEREZ: There's a longing to know and to be known, to reach love and understand it, and there's also the risk of love. This journey into the Amazon is a bit more about that.

Rhiannon Giddens: “Escúchame” from Florencia en el Amazonas, by Danielle Catan.

Aria Code is a co production of WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced, edited, and scored by Merrin Lazyan. Mixing and sound design by Matt Boynton from Ultraviolet Audio, and original music by Hannes Brown. I'd like to give a huge thanks for the help recording this episode to the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance at the University of Limerick, where I'm currently an artist in residence.

I'm Rhiannon Giddens. See you next time!

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.