Silicon Valley’s History of Fumbles with Capitalism

( Julia Burke )

[music]

Kousha Navidar: Hey, everyone. This is Kousha. I'm a producer on Notes from America with Kai Wright. A few months ago, we talked to author, Malcolm Harris, about capitalism. This was right after the shocking failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Specifically, we talked about the complicated origins of capitalism as it shows up today in the United States. That history is a little surprising. If you follow the strands, it helps me, at least, appreciate the full tapestry of our economic system today.

In this episode, Kai and Malcolm talk about the roots of the banking system, the influence of wealth in the pioneering West, and how forces were old-school tech in Silicon Valley. Here's that conversation. I hope you enjoy.

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I am Kai Wright. So many people had never heard of Silicon Valley Bank on the day it collapsed. I had never heard of Silicon Valley Bank, I am going to be honest, but we all just instinctively knew this cannot be good for me because Silicon Valley stands for something in the global economy. It stands for something in the American psyche, ideas like progress, growth, boundless wealth. What does it mean when the place that literally holds Silicon Valley's money goes broke?

There are, of course, still many competing answers to that question and to the question of why the bank collapsed in the first place. For one observer, it comes as a perversely well-timed illustration for an argument he's just spent like 700 pages making that Silicon Valley and California generally has been a laboratory for the worst of capitalism since its founding.

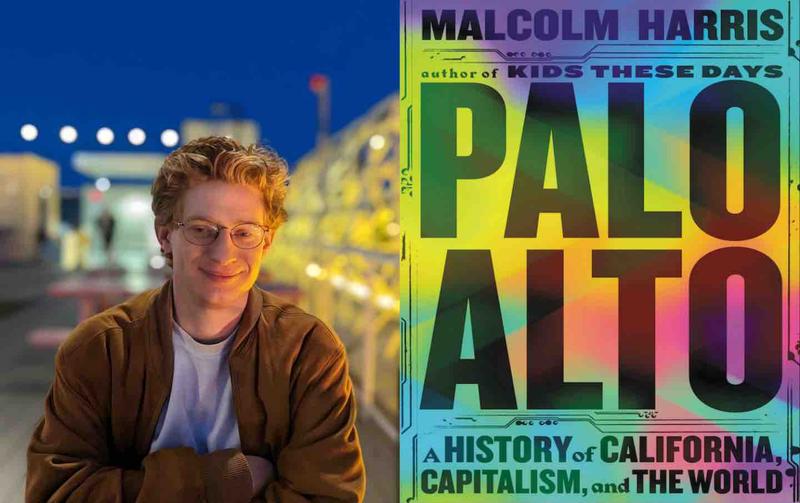

Malcolm Harris is the author of Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.

One of the many strands of history he pulls on in this ambitious book is the more than century-old relationship between banks and the freewheeling, hyper-confident entrepreneurs who have sought fortunes in California. He says that, up until now, the banks have actually been a stabilizing presence in that wild and volatile history. During the Gold Rush, the bank that would become Bank of America knew exactly how to keep everything calm.

Malcolm Harris: When there was threat of a bank run, A.P. Giannini, the founder, would stick a bunch of gold bars on a table in the window and say, "Come in if you want your money. We've got plenty." Even during the Great Depression, that California's banks ended up being extraordinarily stable relative to the rest of the country. I think one of the reasons they could do that is because they had a lot to invest in. They knew that California in the 20th century was a good bet. They knew that the Disney company was a good bet.

Most of all, they knew the California land was a good bet, and so they could put up their money without worrying because they were pretty confident in this future. It's interesting, I think, that this time around, the financial layer that's supposed to tie this industry together, that's supposed to pile the gold bricks in the window and say, "Don't worry about it. This is real," instead, was the one to drive this collapse. It suggests to me that they're running into some limits here.

Kai Wright: Limits of all sorts, but importantly, in Malcolm's analysis, limits to the illusion. Malcolm Harris has now written three popular books that each in one way or another urges us to face the brutal inequality that is part of our capitalist economy. In his new history of Palo Alto, he's arguing that Silicon Valley has for more than a century, been the place where all that excess generated by that inequality gets absorbed and repackaged as progress.

Malcolm Harris: The world has too much money and needs to put it somewhere that can offer really high rates of return based on some really exciting story about the future, and that's Silicon Valley's job. They have to be able to absorb just tons of capital based on some story about the future that they're able to fulfill. The problem with Silicon Valley Bank and such great name, it really was Silicon Valley Bank, is that they had too many deposits and not enough places to put it.

Silicon Valley can't do its job, which is to absorb all that tens, hundreds of billions of dollars of world capital that doesn't have anywhere else to go. This was a real failure by Silicon Valley to fulfill its historical role.

Kai Wright: What exactly is that historical role, and why did it develop in California? What, if anything, does it have to teach the rest of us about the future of capitalism and global inequality? I sat down with Malcolm Harris to get his take on all these questions, and we began with his own childhood as a privileged kid in Silicon Valley. You begin your book in a place that is irresistible to many of us, with a comparison of Palo Alto to the fictional town of Sunnydale from Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

[music]

What are you really trying to get at here? Why are you making that comparison?

Malcolm Harris: Well, I'm personally convinced that Palo Alto is at least partly the basis for Sunnydale. I've never heard that confirmed anywhere, but it's a little too perfect with the bright, shiny California suburb, with the teen death rate that's way higher than it's supposed to be. That was really how I and my siblings and a lot of my classmates experienced growing up in Palo Alto is, on one hand, you have this very promising place that looks great, everyone wishes they could live there, and at the same time, you know there's something sinister going on, that no one wants to talk about. We discussed this haunted feeling as we're growing up there because it was readily apparent to us, and that was really the trigger for me to go investigate this history.

Kai Wright: How was it readily apparent to you? What do you mean by that?

Malcolm Harris: Well, I start the book actually with a story from fourth grade where I just moved to town a couple of years earlier, and we had this substitute teacher in class. She gathered us all up and with crazy eyes, looked at us and said, "Palo Alto isn't normal. It's not. Everywhere isn't like this. You all live in a bubble, and you need to understand that." I was 10 years old, and that's the kind of thing that sticks with you. There were these moments that would be chips in the facade that would suggest there's something much more complex going on in this little town other than happy people making computers.

Kai Wright: The quote of that story in the book is the teacher then disappeared the next day, that when you come back to class, they're like, "Oh, we're sorry that happened to you."

Malcolm Harris: Right, as if to erase it. Instead of erasing it, that sort of stuck it in my memory a little deeper. This is something that was disturbing to the order that we were supposed to be experiencing.

Kai Wright: One of the things that I assume burst that bubble for you or helped you see that there was something weird going on was a national story that I think a lot of people will remember, the so-called Silicon Valley suicides. This is the teen death rates I think that you're alluding to where there were so many young people who were committing suicide, high school students. When did you notice that, and what about it do you think is important backstory for the history you tell?

Malcolm Harris: Those start occurring when I enter into high school, so it's basically concurrent with my childhood, my siblings' childhood, and actually extends into the present. Even as I was writing the book, there was another suicide of a young person who grew up in Palo Alto. The CDC came in and did a whole 200-page report on this spike in suicides in the Bay Area, in Palo Alto in particular, and couldn't come up with a particular explanation. One thing that the parents and the community lobbied really hard for was for them to look at the train tracks and to think about the train tracks.

The train tracks which run through both high schools in the town was a really resonant place for this town, and that was a method of suicide that these kids were using that the CDC normally doesn't count because it's just not very common.

[music]

Kai Wright: The train tracks. Palo Alto was founded on wealth generated by the railroads in the late 1800s, a time when California was the frontier of global capitalism. The railroads connected that frontier to the rest of the country, and settlers came from hither and yon, to make money at any cost, displacing and killing indigenous nations, developing new racial caste systems in order to divvy up the spoils. For Malcolm, this history is both ever-present and rarely acknowledged. It haunts the place, but of course, there are more contemporary specters.

All that perfection that Malcolm grew up with, it's not everybody's experience. The area is divided by a Highway 101. On the Palo Alto side, 80% of the population has at least a college degree, and the median income is nearly $200,000 a year. In East Palo Alto, on the other side of the highway, just a quarter of people have college degrees, and the poverty rate is 12%. This, too, Malcolm says, he and the other children of Palo Alto were not supposed to notice.

Malcolm Harris: Palo Alto has a really strong achievement culture, sends a lot of kids to high-achieving schools, expects to produce a lot of wealth, and justifies its own existence through the success of the next generation. That puts a lot of pressure on children to deserve what they get. Their ignorance is really part of their job because not knowing that history is the only way they're able to deserve what they get. Because if you know the history of the settlement of California and how recent it was and where those profits went, it's impossible to feel like you deserve what you get as a settler of California.

Kai Wright: We've talked a lot on our show, it's about the loss of innocence in the suburbs and the Trump movement and how white flight in cities like places around New York created suburbs that now don't feel like they're providing the innocence to their children, and that's led to the MAGA movement, as I think is one theory of how we arrived where we're at. It's very interesting that we are now talking with you about the children of what everybody else would think of as liberals, similarly trying to hold onto a certain kind of innocence and not being able to do so.

Malcolm Harris: Absolutely. I wrote this book at a time when people, historians in particular, have really been reconsidering American history and the timeline of the American history, and thinking particularly about the 1870s as a re-inauguration of American history, as a second founding of the country. California doesn't get told as part of that 1870s story very often, but it really, really is. It's a crucial part of that story. Palo Alto is formed in the 1870s as part of that story, and so I wanted to tell California's history as part of that revising of the American timeline.

[music]

Kai Wright: Coming up, we go back to the start of the California timeline, and meet the man who created Palo Alto. Stay with us.

[music]

It's Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright, and I'm talking with Malcolm Harris, author of the new book, Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World. The book came out just before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, but Malcolm Harris argues the history he's dissected in this book, not only goes a long way toward explaining that event, it helps us understand the almost mystical role that Silicon Valley has played in our economy. At the center of this story is a man named Leland Stanford.

He moved to California during the Gold Rush where he went into business with his brothers, selling supplies to miners, and eventually went on to start a wholesaling business. It was a lucrative venture, and it allowed him to invest in the transcontinental railroad, the portion that connected California to the rest of the country. That put him in the same ranks as guys like John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and he looked exactly as you might imagine.

Malcolm Harris: If you think of the old-school Robert Baron of the 19th century in big suit with his top hat and his watch chain and the beard, that's Leland Stanford. He really was the frontman for the oligarch class in California in the second half of 19th century. He got that job, not just because he was one of the capitalists behind the railroad which was the real achievement that links California to the rest of the country, but because he was the least clever out of this group of guys, and they sort of stuck him in front because it was a good time to be a capitalist. It was a bad time to be publicly known as a capitalist because this was a period of emerging class tensions.

Kai Wright: This is late 19th century. This is where people are getting upset with industrialization. Laborers are saying, "Wait a minute, what happened in my life?"

Malcolm Harris: They're getting pushed into the factories. They're being turned into proletarians all around the world at a very fast rate, and so they're experiencing this transition to modernity, to a new historical epoch. Instead of looking like prosperity for all, it's looking like, "Oh man, this is a terrible way to spend my life." The workers of Paris, France, for example, rise up and seize the city and the Paris Commune. There are theories of class struggle that are being developed and shared around the world including in California.

[music]

Kai Wright: One of those theories of class struggle is that Leland Stanford, personally, is the problem, so people are protesting outside his home, sometimes physically threatening him. It's a bad scene.

Malcolm Harris: Leland Stanford did what a lot of rich people in cities have done when they have to escape the class tensions that they themselves have created, which is that he moved to the suburbs. The problem at the time was that the suburbs didn't exist yet, and so he had to invent a suburb to move to, to escape these class tensions. That's how Palo Alto is created.

Kai Wright: He moves to the outskirts and creates a horse farm on the land that would become both Stanford University and the city of Palo Alto.

Malcolm Harris: He builds on that land the world's greatest stock farm where he's training horses. Horses at that time represent something very different than what they represent now. At the time, they were the engines of the country. They hadn't been supplanted by powered motors yet, and so they dragged agricultural equipment, they ran canals, street cars. They carried military equipment, anything that had to move.

Kai Wright: They're high-end technology.

Malcolm Harris: Any tech if it had to run was hooked up to a horse probably or mule, some kind of pack animal. Stanford figures that with this stock farm if he can increase the value of all of those horses, horses, in general, by $100 that there were 13 million horses in the United States, that he could provide a value to the country of $1.3 billion. This is what he tells the public. Now that's 30-something billion I think. It's this very like tech plan from the beginning. He and his head trainer, Charles Marvin, build this giant complex, and they think they're going to revolutionize the creation of horses. This is a very old technology, obviously, horses [laughs]. Stanford himself is not particularly experienced, but he's very confident--

Kai Wright: He's going to disrupt horses?

Malcolm Harris: Exactly. He's going to disrupt horses. He's a new kind of thinker. He's not beholden to past folk wisdom. He's going to transform the creation of horses. To do that, they look to Germany where the Reich is being created. This is also something that's happening at the time is the German state is being born. Part of that is the creation of early childhood education and the institution called the kindergarten, but Leland Stanford and Charles Marvin decide they're going to build a kindergarten for horses.

They build a shrunken-down horse track so that they can train horses as young as fast as possible, which previously, according to folk wisdom of the trotting horse industry was that you had to wait till horses get old enough to handle their speed to race them as fast as possible because otherwise, some horses are going to break their legs or tear their ligaments and then you're going to be out for those horses. They say, "No, we need to know the best horses as soon as possible so we can invest in those and shorten the horse production cycle so we can get to market faster."

They do this. They're able to achieve this with this huge capital investment. They create the fastest, youngest horses in the world. They call this system the Palo Alto System. If you go to Palo Alto now and you ask people what is the Palo Alto System, they won't know. Maybe they'll make something up. These are people who don't like not knowing things. Then if you ask them about scalability, disruption, capital investment in new technologies, all the things that were youth and potential, these are the things that constitute the basis for the Palo Alto System, but they're also the things that constitute the basis for a century-plus of Silicon Valley industry.

[music]

Kai Wright: Move fast and break things or something along those lines. Point is, the fundamental ideas of Silicon Valley aren't actually that new, and Malcolm is keen for us to understand that they have always been fundamental to global capitalism as it was pioneered in the 19th century in California. The consolidation of excessive wealth has also always been crucial to its existence.

Malcolm Harris: From the beginning of Anglo-American colonization and the Gold Rush, obviously, halfway through the 19th century, you've got incredible amounts of world capital gathering in California. What this is leading to is huge levels of speculation both on the land and the natural resources, which is leading to the creation of a new capitalist class in this place. Within a few decades, Alta California goes from being the edge of the world that no one can really figure out where the indigenous people are still the majority of the population to the center of world capitalism, and California is generating just huge amounts of wealth.

A lot of that wealth is sticking around in California where it's being reinvested in new promises. You have not only this gold industry that's producing tons and tons of wealth, but that quickly turns into the mining technology industry where they're developing new ways of accessing that gold, and then that technology is being exported around the world. Then you have it being developed as a center of agricultural technology.

Obviously, we were talking about the horses already, but you have huge amounts of money from around the world being concentrated in this place and being deployed to develop new forms of wealth creation. Even though Wall Street is still the economic center of the United States, Wall Street's sending tons and tons of capital to California because that's where it's seeing growth.

Kai Wright: Because it's growing and growing and growing and you're getting returns and returns and returns.

Malcolm Harris: It's the frontier for capital, and the frontier is always where those returns are highest.

Kai Wright: Also, at the frontier for capital is where there is a huge influx of labor, of workers. I'd love you to unpack that a little bit. First off, just talk about the kind of labor that's showing up in California and what it does to challenge the racial hierarchies.

Malcolm Harris: From the very beginning of the Anglo-American period, you have people coming from all over the world to California to try and make something of themselves. There are lots of people who want to be Gold Rushers. It's not just white guys from the East Coast of the United States who come to California for the Gold Rush. People are coming from China, people are coming from South America, people are coming up from Mexico, people are coming from Russia, people are coming south from the Northwest Territories.

In that cauldron, the pioneers establish the white state as this sort of cartel of miners where they're able to exclude non-white miners and non-American miners from the best mines in the best territories. This is the basis for California governance in the first place. At the very beginning, you've got, not a melting pot, but instead this area of really intense racial competition. Then as you transition into the agricultural industry, and you've got more immigrants coming again from all over the world, you have real struggles at the level of the labor market and at the legal level over who's going to be allowed to be white, who's going to be allowed to stay and under what circumstances.

Kai Wright: Because you've set up this whiteness cartel and so now you've got a police who gets in and out of it as the people change?

Malcolm Harris: Because whiteness in the West meant access to the settler role and there was a lot of wealth to be had there. Whiteness was really worth something here in California but only if you could control who had access to it. You see the Chinese Exclusion Act coming out of California at the end of the 19th century. You have the Alien Land Act at the beginning of the 20th century where Asian people are forbidden from owning land. Then you have also these Supreme Court cases arising from formal challenges to the racial hierarchy in California.

We have a Supreme Court case about, is a Japanese person white, and Supreme Court says no. Is an Aryan from India, from the northwest part of India with light skin, are they going to be considered white? The Supreme Court says no. Is someone from Syria going to be considered white? Yes. These are arbitrary choices that are being made by people. Again, in our modern age, these are not ancient decisions, and we can see them being made by American legal structures that are forced to deal with the challenges to racial hierarchy that are occurring in California because people want to own land. They want access to what are being described as the privileges of whiteness, and they struggle over that.

Kai Wright: One of the things that's always hard to disentangle for me with these kinds of histories is you have the whiteness cartel set up, and then people compete for entry into it. My argument is always like, the closer to Blackness, the less likely you are to be let in, and the closer to physical whiteness, the more likely you are to be let in. California history complicates my worldview in that way, I think. What is your assertion of any pattern that you see in who gets to have access to the whiteness cartel?

Malcolm Harris: So much of it is about the labor market and how the labor market is shaking out. Some of these are literal cartels. They're agriculture cartels, and so if you're in the prune cartel, are you in the raisin cartel, are you in the apricot cartel? This is a cartel made up of Armenians, Russians, Portuguese, Italians, people who have to be allotted the privileges of whiteness in order to run these industries. At the same time, they're able to exclude or marginalize other groups from these organizations as forms of creating them.

I quote some newspaper article from the early 20th century where they're talking about, oh, the racial feeling among the Russians and the Armenians and the Italians and the Portuguese faded away as they all voted to join the agriculture cartel together. At the same time, I think you're right that there's a just colorist spectrum. Blackness is an invariant in this period throughout the world that Du Bois talks about the question of the 20th century being the question of the color line, and that color line's drawn very clearly in California in ways that don't necessarily have that many exceptions.

It's arbitrary, but it's not random. In the early period when they're still trying to figure out and they're just drawing from phenotypical, literally the color of your skin, it was like they were ruling that a light-skinned person from India could marry a light-skinned person from Mexico because they were both people of color and their skin wore the same color, and a dark-skinned person from Mexico could marry a dark-skinned person from India. That was okay because their skins matched, and they would write on the form, when it said race, they would write brown because their skin was brown.

These determinations of the bounds of whiteness, these are things that have to be worked out juridically and practically. What I think is interesting is that so much of this happens in California, which again is such a late addition to the union, and that it ends up being so quickly a laboratory for these questions, I think, is one of the things that makes it the center of American capital in the 20th century.

Kai Wright: Just on the basic of why, why is it the place that this gets worked out and not Alabama?

Malcolm Harris: Well, partly because it was drawing people from so many places in the world. Part of it it's the literal physical location in the world on the Pacific rim, and that there was so much space to be colonized there. It was, again, the frontier at this point where capitalist norms and practices are being established, and so then quickly it becomes a laboratory for capitalist technology. That means, on the one hand, mining engineering, the hoses that you're using for hydraulic mining, engineering, the seeds and the genetic practices, but also these technologies of racialization, which are a capitalist technology of production.

Kai Wright: Meaning the sorting of human beings by race in order to sort them in a labor market?

Malcolm Harris: Absolutely. The pseudoscientific segregation of the labor market was something they experienced as a scientific innovation. They were constantly consciously figuring out race according to these new ideas of genetics that were being determined at the same time as they were figuring them out politically.

[music]

Kai Wright: Having heard all of this history from Malcolm, I honestly couldn't quite figure out what it means for right now. Earlier, Malcolm told me that the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank suggested that this model is hitting its limits, Leland Stanford types moving fast and breaking things and coming up with more and more bizarre ways to slice this up racially and consolidating huge amounts of wealth in this one regional spot, and then leveraging it for still more consolidated wealth.

I wonder, can it no longer sustain itself? Malcolm is arguing that the core challenge that Silicon Valley Bank faced was that there aren't enough viable new horse farms into which they can pour all of this consolidated capital.

Malcolm Harris: I don't know that they have a long-term plan to address that besides--

Kai Wright: Because they've run out of things to speculate on?

Malcolm Harris: Well, they're running out of stories to tell, and so they have to tell increasingly implausible ones about colonizing Mars or artificial general intelligence. I think it's very funny that Sam Altman and the OpenAI folks have convinced the public that they can spin straw into gold. He has to keep that same smile on his face 24/7 or people are going to realize that his company isn't worth $100 billion because it can't actually do anything. I think that's where they find themselves.

At the same time, the world hasn't found another answer to the problem that Silicon Valley is supposed to address. It doesn't have another story to tell. I don't think we're going to look back on Silicon Valley Bank as an important learning experience, instead, it was going to be an experience for the richest to consolidate again and call the weakest out of the herd.

[music]

Kai Wright: Malcolm Harris's new book is called Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.

[music]

Notes from America is a production of WNYC studios. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts or on Instagram @noteswithkai. Mixing and theme music by Jared Paul. Reporting, producing, and editing by Karen Frillmann, Vanessa Handy, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. André Robert Lee is our executive producer, and I'm Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.