The Secret Tapes of a Suburban Drug War

( George Joseph )

Kai Wright: Hey everybody, just a heads up before you listen to this episode, there's a good bit of salty language in it including at least one really offensive word. If you're not in the mood for that, or if you're listening with somebody you don't want to expose to that, then try this one later. Thanks. Otherwise, enjoy. This is the United States of Anxiety- a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

Reporter: … in Mount Vernon. A city police officer taking legal action against the city and the department.

Dr. Robert Baskerville: The question has been called: who shall police the police?

Andom Ghebreghiorgis: Think about what it means in our community to keep people safe and to hold people accountable.

Jason Myles: It affects me when I see stuff like that, because I've lived it, but I'm not silly enough to think that you can de-fund that away. That doesn't go away.

Ava DuVernay: Something about the George Floyd murder really knocked me to my knees. I had to ask myself what was different about this. For me it was bearing witness to that officer looking right into the camera as he murdered him.

Rep. Jamaal Bowman: You are hired to protect and serve and uphold the law. You are not above the law.

Kai: Welcome to the show. I'm Kai Wright. For huge numbers of people, George Floyd's murder was either an awakening about the wanton violence and impunity that defines so much police behavior in Black neighborhoods, or it was a reminder of the urgency of the problem. The moment seemed ripe for change. A lot of that energy got subsumed in the overall outrage over Donald Trump. Even today, a lot of people were fixated on his speech.

He just continues to take up so much space in our public conversation. The problems with policing, which sent so many people into the streets this past summer, they haven't gone away either. We are going to return to them as often as possible on this show, we are particularly interested in how much unaccountable unmonitored power police wield as individual officers and as departments overall. As we know, that kind of power can corrupt.

One of my colleagues in the WNYC newsroom, George Joseph, has spent months investigating allegations of such corruption in one police department in a small city, just outside of New York in a town called Mount Vernon, North of the Bronx. George obtained hours and hours of audio recordings tapes that were secretly made by a Mount Vernon police officer, who was appalled by what he witnessed. Multiple allegations of illegal behavior, stuff outright theft from residents and brutality associated with that behavior. The tapes are startling.

Murashea Bovell: I've never seen it on the level that I've seen it in Mount Vernon dude.

Campo: One thing about this deployment is the racist deployment dogs.

Bovell: I've seen brutality for a confession. I've seen robberies.

Campo: Something needs to be done about this department. Something needs to be done.

Kai: We're going to spend this whole show with George Joseph in Mount Vernon, learning the results of his investigation. To me, it's a story about the fever that consumed so many cities as they raced into the war on drugs, decades ago at this point. How the choices they made in that fog still define so much about law enforcement in America. To start the story, I asked George to set the scene in Mount Vernon.

George Joseph: Mount Vernon is a small really community rooted city. It's just four square miles, really small, 70,000 residents, right across the Northern border of the Bronx. A lot of new Yorkers don't even know it. For me in fact, the first time I heard about Mount Vernon, was in that Nas song, The World is Yours from Illmatic.

[music] Nas: The world is yours. Everybody in Mount Vernon, the world is yours…

George Joseph: He shouts out Mount Vernon, one of the centers of Black culture in New York. How about that? This small community has produced so many famous people, artists, actors, Denzel Washington. Back in the '60s, Nina Simone was next door neighbors there with Betty Shahbaz.

[music] Nina Simone: When you are young, gifted and black!

George: In the eighties, a bunch of hip hop artists, Sean Puff Diddy, Heavy D, they all came up through Mount Vernon.

[music] Heavy D: If you like it so far, you think you want more? Come up town and I’ll take you on a Heavy D tour of Mount Vernon, Vernon, Vernon…

Kai: That I definitely had no idea. It's the Harlem Renaissance in Mount Vernon?

George: At least in Westchester. I mean, you could hear Heavy D how much he loves this place. These are his streets. These are his shops where he grew up.

[music] Heavy D: Born in Jamaica, Mount Vernon I grew, but I still do my shopping on 4th Avenue. Buy my Nikes from Chambers, then walk down the block. Get the gear that I wear from Buddy's Big Men Shop…

George: It's also historically been a very segregated town. There's the phrase across the other side of the tracks, that's literally the case in Mount Vernon. The Metro-North Rail line just cuts right through the city.

Train Operator: Stopping at Mount Vernon East.

George: The North and South are divided North being historically Irish and Italian and South being historically Black. That segregation has been there in intense, and it still exists to this day. One of the people I spoke with in my reporting is Alan Seward.

Alan: Go, go back a little bit into the degree you can try to be chronological.

George: We started back--

George: He was a young Black kid growing up in the '70s and '80s and remembers just trying to go up to the North side cause that's where one of the movie theaters was.

Alan: Back in the days. That was the only movie theater, top of the hill,

George: The Italian kids and even adults would chase him and his friends out because he was Black.

Alan: Then the white kids chase us back home, "Get the n-ggers." Boom, we've got a jet. Don't trip and fall, because if you're caught, I'm out. I already know I'm getting away. Sometimes you've got to try to go back, pick somebody up. Because if you get caught now trying to be helpful, that'll get you beat up.

Kai: This is as late that the '80s?

George: Yes, this is definitely as late as the '80s. It was one of those white ethnic enclaves that had a very rigid and hostile identity towards anyone that didn't come from the "neighborhood".

Alan: You already knew, don't come in this town with no BS if you ain't from around there, bottom line.

George: In this kind of segregated world, there is just a lack of opportunity and downright poverty for people like Allen. With the expansion of crack in the '80s, the city was just completely transformed.

Alan: Seeing some of these dudes turn into ghetto celebrities overnight. The change was so crazy

George: He's just a young man, seeing people that barely had any money last week, all of a sudden, they have nice clothes, nice shoes, everything they want.

Alan: You just was begging for a fucking piece of chicken. Now you driving the newest Benz.

George: He was a kid without much money. He wanted that stuff. That's what he pursued because that was the opportunity that he saw available to him. When did you start dealing? How old were you?

Alan: I was 11, started out selling $1 joints.

George: He was a clever kid. He used his newspaper route to covertly sell on the streets.

Alan: I used to get up at 6:00 in the morning throwing out the papers, so it didn't look suspicious when I'm at this door, or at this car. Boom, I said, when I'm at the car, I could be giving them a penny saver and a bag at the same time.

George: I don't want to romanticize it too much. The violence that came alongside the drug trade was real. Alan remembers being a kid on his block. It was a dangerous place to be. People were getting shot there all the time and that was just something he was used do.

Alan: My block was crazy. They called it the Red Zone. My block was dark, people would get you to walk down there, and you just hear the shots and dudes cutting through backyards.

George: The response to all of this was more pressure from law enforcement. About a decade earlier, New York State had passed some of the harshest drug laws in the country known as the Rockefeller drug laws. Before crack, heroin was the big problem. None of the rehabilitative programs or soft criminal penalties were really working in lawmaker's minds.

New York starts cracking down zero tolerance on even small drug users, small dealers, all of a sudden, they're going to prison for years. That model started in New York, but it spread across the whole country.

Kai: This policing you're describing, how did that look on the streets in Mount Vernon then?

George: In Mount Vernon and cities across the country, to be fair, police departments begin deploying these specialized units. That were given carte blanche to go out and do whatever they wanted. Ride around in unmarked cars, wear regular clothes, not uniforms and just clear off corners, push people up against walls, whatever they needed to do to clear out problem.

Kai: It's the stuff we're used to seeing from The Wire and NWA videos. These cops that are as menacing as the criminals.

George: That was understood. We need people to be as tough as the bad guys. The idea was if we basically search every young Black person in the hood, who's walking around, maybe we'll find some guns and drugs. Maybe by doing that will scare them into not holding the things that are associated with this violence that we're seeing. That amount of power, which basically throws out all constitutional protections we have in real practical terms, there was a lot of temptation to commit abuse.

In those days, one of the most notorious officers was this dashing drug warrior, a detective named James Garcia. Here was this handsome light-skin cop with a big beard, tall. He even appeared on TV. He was on the CBS show called Top Cops, and he gets to make a monologue to the camera about how you really have to be in the war on drugs to fight it.

James Garcia: Narcotic work is risky and sometimes fatal. My first goal was to make arrests. The second is to go home. Sometimes I'm asked, why I do what I do. I answer. If you want to win the drug war, you have to be in it.

George: But the dark underside, which they didn't show on TV was that residents like Alan Sewer had been complaining about brutality from the Mount Vernon Police Department for years.

Alan: My first encounter, I had the weed one night--

George: Alan he has this one terrific story as a young kid.

Alan: I was in front of my building, when they snatched me this night.

George: He had his joints on him because that's what he was selling back then, and two officers pull up.

Alan: I can tell you. It was summertime, but it was probably eight o'clock at night. They were cruising through the hood, they had the brown square--

George: Alan remembers is brown Chevy.

Alan: Impala, old school back then. They pulled up, jumped out, dudes start scattering and all that. So, I'm in front of my building, I don't feel I got a run. He said, "Come here shorty," and he started patting me down--

George: They search him.

Alan: I got 10 joints in the cigarette pack. I used to keep it in the empty cigarette box, because they already rolled up. He said, "Oh, so you smoke cigarettes?" He looks in the pack and he sees that I got the weed. They throw me in the car, now he's asking me, "So how old are you, anyway?" I said, "I'm 15." He's like, "You're sure you're 15?" I'm like, "Yes, I'm 15. I got my high school ID card in my pocket."

George: Alan assumes that he's going to go to the police station, but that's not what happened. Back then 15 was the age right before you could be charged criminally in New York State. So instead of taking him to the police station, Alan notices.

Alan: We're going straight down Union.

George: They're not on there, like what's going on?

Alan: They took me straight on down right to Brush Park.

George: They pull up to this parking lot in a park nearby not far from his home.

Alan: I'm wondering, if they're going to just let me go because--

George: But they take them out and Alan says, one of them starts punching him right in the gut.

Alan: They folded my little ass, like a beach chip. I don't even remember, I might have spit out blood.

George: He says that he was knocked down to the floor and left there and they drove off.

Alan: I didn't get up until 4:00 AM. I got a whooping when I got home. It's crazy.

Kai: Was there ever any accountability for this police department or for this top cop James Garcia for that matter? Did anything ever happen to him?

George: A few years later in the mid '90s, the FBI was investigating corruption on the Mount Vernon Police Force. As part of that investigation, they planted a duffel bag full of cash and James Garcia and a supervisor ended up going into this apartment where this bag had been planted full of cash. The FBI had hidden a camera there and Cop Garcia on tape, taking the cash, putting it into his vest and handing some to his supervisor.

He pled guilty along with two others for this corruption and was off the force, but that really didn't change the fundamental DNA of policing in Mount Vernon. These narcotics units, these specialized squads, they continued for decades to have their way on the streets of Mount Vernon and Black communities across the country like Mount Vernon and the corruption scandals continued and continued.

Kai: Coming up we'll hear how allegations of corruption and abuse are still a problem for the special narcotics unit within the Mount Vernon Police Department and how one officer tried to change it.

[music]

Kai: Okay. George, you described how the response to crack and the rise of violent crime and all that, that was going on the '80s. It led the police departments to create these special units. How did that then evolve over the decades?

George: All of these departments basically allowed these squads of officers to run the streets, gather information and hopefully bring in arrests of people for guns and drugs. But you've basically allowed a unit to be out there without any supervision and all this knowledge about where this black-market money and drugs, which is another form of money are stashed. So pretty soon officers were like, "Oh, why don't I take a cut of this?" We see this in cities across the country.

Reporter: In the indictment unsealed today, federal prosecutor said the six officers stole upwards of $500,000 in cash.

George: In Philadelphia, there was a narcotics unit scandal where the feds caught this small group of drug police for grabbing dealers and hanging them off balconies and stealing tens of thousands of dollars in cash.

Reporter: In another several officers stole cocaine office suspect and then sold it on the streets themselves.

George: In Los Angeles. You had an anti-gang unit called CRASH.

Speaker: In which officers routinely planted evidence, framed innocent people to secure arrest and convictions.

George: We see how the police leaders basically were being permissive about whatever they wanted to do. They had this identity of themselves as warriors who had no rules whatsoever.

Speaker: Kind of like a gang themselves.

Kai: It's interesting because we have these two counter-narratives happening in the country alongside that if we remember in the late '80s and early '90s. Where in like Hip hop and in Black culture

Speaker: The cops in America actually kill kids.

George: People were narrating that corruption that you're seeing.

Speaker: Until these cops realize that we're not just going to continue to get our butts kicked in the street and we will retaliate. They're not going to act like human beings.

George: It feels like it all came together politically at least, in the 1994 crime bill. This is the piece of legislation that most people probably know when they think about criminal justice, particularly because-

Speaker: This is a tough, smart crime bill--

George: -our new president, Joe Biden played a huge role in crafting and promoting that bill.

Speaker: A bill that has 51 death penalties, 100,000 cops, tens of thousands of new prison cells, and the list goes on.

Kai: What role did it play in the evolution of these units?

George: When we think of a bell like 94 crime bill, we should think of it as the culmination of decades and decades of punitive pro-carceral policies. But it's important to remember that this bill was sending a signal at the federal level to all localities across the country, keep doing what you're doing but actually hypercharged it. Bring in more arrests, we'll give you more funding. It was almost an affirmation of what tens of thousands of localities and police departments and prosecutor's offices across the country were already doing themselves in these very localized and self-directed ways. In increasing funding for the war on drugs, they only further empowered the kinds of abuses that residents in streets of cities like Mount Vernon were already suffering.

Kai: Instead of looking at the corruption, instead of looking at the problems and saying, "Oh, we better rain this in some." Actually, this is literal money thrown into the fire to make it burn bigger. Then what does that look like in a place like Mount Vernon? What happened then?

George: In the decades that followed in Mount Vernon, especially in the late '90s, you did see a decline in violent crime, just like as happened across the country. But in Mount Vernon, unlike in New York city let's say, that decline wasn't consistent and thus the same tactics were not disbanded. Even up through the 2010s, the narcotics unit in Mount Vernon had several members who were the subject of civilian complaints for stealing money, for really humiliating strip and anal cavity searches. For day-to-day frisks that made residents feel like they couldn't really walk around in their community without the threat of police putting their hands on them with or without justification.

Speaker: I can't ask a question?

Antonini: You want to let me talk?

Speaker: Go ahead.

Antonini: Don't interrupt.

Speaker: Okay.

George: One of the officers who many of these complaints centered on was a detective named Camilo Antonini.

Antonini: If you know me and you know what I do, and if I come to you and I tell you to do something, there's a reason. Wait--

George: For example, there's this one resident I met in my reporting. He's a Black resident. He sent me a video of one of his encounters with Camilo Antonini.

Antonini: If I'm not going to get you dirty, at least I can ruin the day.

George: Antonini is a veteran of the Mount Vernon Police Department. For many years he was on the narcotics unit as a detective. He came from the NYPD, he also served as a Marine.

Antonini: Wow. I'm not going to harass you.

Harassed Resident: Okay, but what's the reason why you're making me--

Antonini: I'm not going to harass you.

George: Antonini, just walks up-

Antonini: I'm going to ask you for a favor.

Harassed Resident: What's that?

George: -gets right up in this guy's face.

Speaker: There's no favors. I don't do favors.

George: And starts frisking him and feeling up his pant.

Antonini: Swallow.

Harassed Resident: Swallow what?

Antonini: You can swallow.

Harassed Resident: I haven't got nothing in my mouth. Why are you asking me--?

Antonini: Open your mouth then? Swallow. [audible gulp] Okay, good.

Harassed Resident: Why are you asking to open my mouth for? If you're not harassing me. What's the purpose?

Antonini: It's my job.

Harassed Resident: What's your job though man? Come on, man.

George: It seemed like he was pretty pissed off about this video he was taking.

Harassed Resident: Why are you frisking for? What's the reason? Tell me.

Antonini: Take it easy.

Harassed Resident: I'm asking you, tell me why you're frisking me?

Antonini: Spread. Spread.

Harassed Resident: Spread what?

Antonini: Spread.

Officer 2: Your feet.

Harassed Resident: My feet are spread. How wide do you want me to go?

Antonini: You recording it, right?

Harassed Resident: Exactly, but you're not telling me--

Antonini: What time is it?

Harassed Resident: What time is it?

George: He is standing on the street, talking to his friend, and this officer feels like he has the right to touch him in this very personal way.

Harassed Resident: It's 7:14 in the evening.

Speaker: His always harassing somebody, always.

[music]

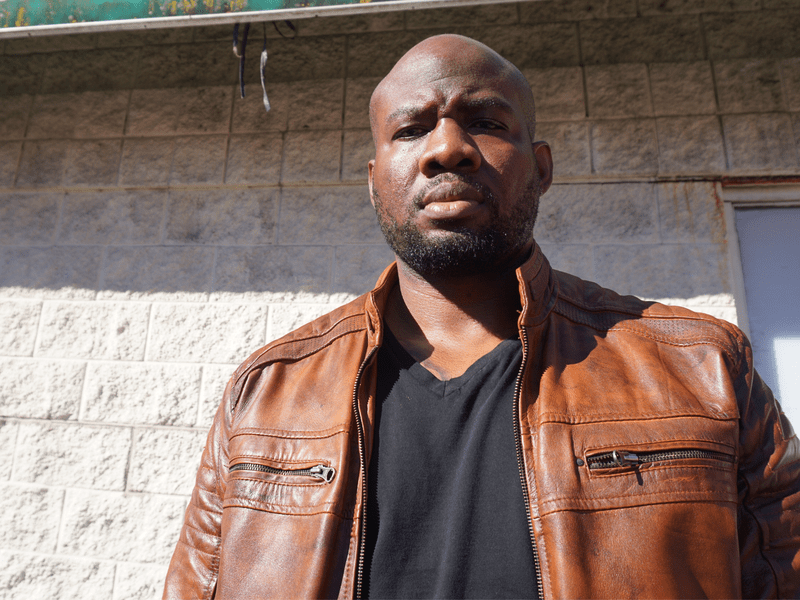

George: Around this time, Antonini was really getting a reputation on the streets. Alan Seward, the resident we talked about a lot earlier--

Alan: No, no, I'm a hood legend, you know what I'm saying. Everybody in this town knows me. I'm born and raised here.

George: By this point, he'd become a well-known drug dealer in Mount Vernon, and he'd paid a price, he'd been in and out of prison for decades.

Alan: I came home from prison in 2016, February 25th.

George: For what?

Alan: Drug possession of cocaine.

George: By the time he comes back, he's hearing allegations about Antonini that remind of what his childhood was like, growing up in the '80s with the police department. Antonini was just well known.

Alan: When you hear the same stories all around, then you that they're true.

Kai: By this point, Alan is how old? We left him at 15, but how old is he now?

George: By this point, he's in his late 40s. After all these years, he's starting to get tired of the drug game.

Alan: You get tired of going to jail. Dudes come in game, thinking it's just, "Get some drugs and sell it." No, it's really a job. You got to watch out for the snitches, the informants, the undercovers, the detectives riding, the blue coats, the good samaritans in the window that I want to call community watch. It's a whole lot of stuff that goes in tail with this. Then you got to measure and weigh everything, and make sure the get your proper amount of money back.

George: Can't be a slacker.

Alan: Yes. You've got to make sure that you're making your profit, not just to be doing just to do.

Kai: If he's getting tired of this, but it's been his primary source income. What's he going to do for money now?

George: I mean, he has some of his hustles, but he's also starting to take on low-wage blue-collar work.

Alan: I get a job.

George: What do you do in that job?

Alan: I'm a teacher's aide, slash security guard, cause--

George: He was just starting to think about doing something new with his life, but that plan didn't really work out.

[music]

George: Just go from the beginning of that night, where were you?

Alan: Okay, I was in the Bungalow, $2 Dollar Tuesdays.

George: One night, Alan was at his favorite bar, which is in the south side of Mount Vernon, predominantly Black.

Alan: I like this spot. I go there. I frequent it.

George: He was playing pool there, and he bets people for money by playing with one hand. He's called the one-handed bandit. You play with one hand sometimes to beat win, that's part of the bet?

Alan: All the time. If the left-hand touch the stick, you automatically win. I chalk-up with the one hand, everything.

Kai: Alan is very good at pool is what we're learning.

George: Yes, he's good. He was having a good night that evening, and he had won a lot of games.

Alan: The guys just think they can win. They just want to try. Everybody wants to beat the best. "Oh, you won't beat me with one hand." Then I got to show them, too.

George: As he's in the middle of one of his games, he's holding his pool stick, he's aware of his environment. He notices two guys in hoodies, standing by the jukebox.

Alan: One guy looks like a white guy, could be Spanish, and then the other guy was Black.

George: He's been a guy that has been in plenty of run ins himself on the street over many years, and he's a little concerned, like, "Who are these guys in the bar?" All of a sudden, they start approaching him.

Alan: Now I got the pool stick, start to sling it.

George: Ready to use it if he has to.

Alan: He pulls the badges out.

George: They're police, and one of them, he says, is Camillo Antonini.

Alan: Then I put the pool stick down. I'm like, "What the fuck is y'all running down on me for?

George: The cops drag him out of the bar, -

Alan: Take me through the crowd-

George: -and they take him out on to their unmarked car, which is parked down the street.

Alan: He sticks me in the back seat like this. I'm like, "What the fuck?" I'm on my head. I'm fucked up.

George: Instead of just taking him and processing him at the station, he says they pulled down his clothing-

Alan: He starts taking my pants down.

Kai: On the street?

George: Yes, on the street. He says he frankly felt scared.

Alan: My first thought was, "He's going to try to rape me or something."

George: According to him, his backside, at this moment, is just exposed to anyone who happened to be outside. He says what ended up happening was Detective Antonini searched his anal cavity, looking for drugs, but they didn't find anything.

Alan: Then they pull my shit back up, put me in the car, and then took me to my daughters' apartment on 1st and 3rd.

George: Police at already been searching his daughter's apartment. You walk in and what happens?

Alan: When I walk in, I'm cuffed. My granddaughter runs up, crying, "Papa." She hugs me and shit. I see my daughter is cuffed. Everybody in the house is cuffed except for my two granddaughters.

George: Who else is there?

Alan: My daughter--

George: Just like that, Detective Antonini, Alan says, goes into another room and comes back holding 10 grams of a white substance, presumably cocaine.

Alan: Then, he's like, "Hey, look at this. I found 10 grams." My daughter yells, "Dad, they searched before you got here. They didn't find nothing." I said, "Oh, you're could put that back in your pocket."

Kia: The implication is that he planted the drugs.

George: Yes, that's what Alan says. These drugs weren't his. The detective had suddenly pulled them out. Hold on. When you're in the apartment and Antonini comes out with this bag, what are you thinking?

Alan: He's trying to set me up.

George: Going back, what does it look like?

Alan: It's a glassine bag, but it could have been baby powder. I don't know what he had.

Kia: Then what happened?

George: Police take him to the department, and he says they put him in small interrogation room.

Alan: This is the fuck-you-up box. You could tell.

George: How did you feel, going into that room?

Alan: Oh, nervous as hell, and I'm handcuffed, too.

George: After all this stuff that's happened, this is according to Alan, Antonini is suddenly coming to him with a deal.

Alan: This is when he starts telling me, "It's just me and you in here. I'm saying to you man-to-man, you got kids, you don't want your kids to get shot. The only thing that could kill me is a gun. I want the guns off the street. I don't care about the drugs. If you tell me where somebody could get a gun, right now. You could take the 10 grams, go out this door right here," there's a door right there. "You can go out this door right now. You can get money, and you won't got to worry about getting arrested. All you got to do is just give me information."

Kia: This is all quite a remarkable set of events. If even a little bit of that is true, it's really shocking. They found these drugs that he says were planted, taken into this room, and now, they want to say, "Okay, here's what we want in return."

George: Exactly. The deal that Alan says he was offered is not something he was used to. Alan has been in the drug game at this point for a long time, and he's normally used to police saying, "If you give us some information, you can walk off this charge, or we'll be lenient on this charge." That kind of thing. What he says Detective Antonini offered him in that room, by themselves, was, one, "You can go. Take these drugs that I supposedly found on you and go deal them, and I'm not going to have a problem as long as you're giving me information."

Alan would become like a factory of arrests for them. It's not only a gift, a goody bag with drugs, but also future impunity, which is not what Alan was used to.

Alan: I was like, "That's how you do it? Is this how you've been getting these guys?" He was like, "You'd be surprised how many rats I got on my team." I was like, "I'm not surprised, but I just know you don't got this rat. You don't got me on your team."

George: He felt that really violated his street ethic, like you don't work with cops, you don't accept gifts from them. According to him, the consequence was he was going to be charged, and he feels, who is going to believe his story that he was coerced, that he was planted on. I mean, it was his word, "A Black drug dealer from the hood in Mount Vernon versus this detective decorated, highly productive officer."

Alan: Some guys, cause if they're green, and they never been through anything, they're going to be shook. They're going to be like, "Oh, men, you really are--" He's like, "Yes, there's 10 grams. It's going to stick, and you're going to go up North for 12 to 16 years, or you can tell me who got the guns right now, and I'll let you go out that door right there." Because you're not even on record as being arrested, so it's easy for him to let you go.

[music]

George: What Alan and Antonini the detective, in that moment didn't know was that someone inside the police department had started to gather evidence about what the department, especially the narcotics unit, had been up to for many years.

Bovell: It's totally wrong. You know what I mean?

Campo: It's very bad now in Mount Vernon.

Bovell: It's really bad. It's so blatant in Mount Vernon.

Campo: In early 2020, last year, I was handed this big pile of phone recordings from a patrol officer named Murashea Bovell.

Bovell: I'm not playing, men. I'm not playing because the shit needs to stop.

George: A officer in the Mount Vernon Police Department, came to the department around the same time that Antonini did.

Bovell: Everything they do is against the law.

Campo: Yes.

George: Bovell says that he had witnessed some of the same kinds of misconduct that residents had been complaining about for years, involving Antonini and other officers in the unit.

Bovell: With everything that's happening with the corruption, I'm putting light on them--

George: He decided to document what was going on by recording his fellow officers.

Bovell: Antonini's been slapping people around for some time and that's what he does. He uses intimidation tactics to allow people to be scared of him in the street.

George: We're talking about collaborating with drug dealers, of beating people up in handcuffs in the station.

Bovell: I wasn't having it. Being a part of this corrupted unit didn't sit right with me. Listen he has stolen money. I'll tell you when I go search on warrants, he'll be grabbing money like, "Yo, you're seeing this. Ain't nobody seeing this?" Ready to pocket that--

George: These sorts of allegations were twirling around the whole unit and he wanted to get evidence to prove that what he was saying was not just his word, but something that was really happening that no one could deny.

Bovell: I work in a police department where I know that things can be covered up. That's the reality of it. That things that are out of your control can be controlled by someone else.

[phone rings]

Campo: Yo.

Bovell: What's up?

Campo: What have you got? What are you doing?

Bovell: Hey man--

George: One of the officers who Bovell recorded the most is a guy named John Campo who had also been on the force for several years.

John: But I had never seen it on the level that I've seen it in Mount Vernon, dude. I had never seen anything like that before. It's like its own little country with a dictator.

George: You can hear in the tapes that Campo sounds uncomfortable with the things that are happening around him and with the people that he's working with every day.

Campo: One thing about this department, is the racist department dogs. You got to understand.

Bovell: Hold on one second, hold on one second. Sorry, it's my daughter,

[kid crying]

Campo: What happened?

Bovell: I have to make a bottle for my son.

Campo: I can't work with racist people. That's not how I am. That's not how I grew up. It's not me. My kids are Spanish. One of my kids is mad dark.

George: It's not just like Campo is talking about things he saw, although that is a lot of it.

Campo: They had their undercover identify the wrong suspects on numerous occasions after they were told that that wasn't the person that he brought them. They're going to indict people on fake charges or whatever the fuck it is, that don't deserve of being indicted because they weren't even the right person that he brought to them.

George: He also talks about things he was involved in.

Campo: What I'm trying to tell is this-

George: For example, there is a part of the tapes where Campo is describing he and a colleague arresting this well-known drug dealer.

Campo: We ran up on this dude because they're-

George: For shooting craps on the street with some of his friends.

Campo: They're rolling dices from the building and I think it's wrong--

George: That's just low-level arrest, but what happens next is kind of remarkable. Campo says the guy basically gives him an order.

Campo: The dude looks to me like, "Yo, Campo I've got 40 rocks in my pocket, take it out of my pocket and stash it somewhere."

Bovell: Wow.

George: The guy has crack cocaine in his pocket and he's telling this police officer to go stash the drugs and hide them.

Campo: I took the 40 rocks of crack out of his pocket and put it in my sneaker.

George: He's basically giving the police an order to do things highly suspect-

Kai: What?

George: -so that he can get the drugs back after he's processed at the station for this low-level dice rolling violation.

Kai: Because it's so known on the street that this is the kind of thing that goes on. Campo is on tape describing this?

George: Yes. Campo makes it clear that this guy was one of their best informants who had been part of this sort of arrangement where dealers were allowed to do whatever they wanted, putting the drugs back on the street.

Campo: They're allowing him to sell drugs with a free reign and then just pick off the guys that he sells to.

Bovell: Get the hell out of here.

Campo: I swear to God.

Bovell: They let the dude keep the sells on the drugs?

Campo: Yes, that's what they do. That's not part of the rules, bro.

George: We see very clearly from the way Campo's talking, he feels like this kind of behavior is being rewarded by supervisors.

Kai: Wow.

Campo: He's like, "John, did he have anything on him?" You're like, "Yes." It's like, "Oh, did you stash for him?" You like, "Yes." He's, "All right. Good"

Bovell: Oh, bro.

George: The important thing to understand here and what these recordings, these tapes reveal. Is that the unit cared more about keeping these kinds of people out on the streets so that they could generate arrests in collaboration with them, low-level drug arrests. Rather than actually going up the ladder and getting the people that were bringing in large quantities of drugs into the community.

Bovell: This is backwards. This is just numbers.

George: It wasn't just coercing dealers after they had been arrested. Someone like Alan says they were willing to plant drugs on people in order to force them into this arrangement where they ran the streets, racking up these numbers as an end in itself.

Bovell: It's dumb. When I was in narcotics, yo, I went and I got big shit, man. I'm focused on shit that's poisoning the community. I'm not trying to poison the community. What am I doing? I got to go home, that don't make me feel good. If I'm not doing the right, just going backwards. Why? For what?

Kai: George, listening to this, what's so striking to me is you, you can't really make a bad apple argument here. When you think about abusing individuals, maybe that's like this one officer who's just really awful, but this is so mundane that it feels systemic.

George: This has been going on for years, according to Bovell. In the tapes, you can really hear him trying to draw what Campo knows out of him.

Bovell: Seriously, this is from me to you off the record. Give me somebody, date and time, that Antonini fucked up, you don't worry about nothing.

George: Encouraging him to tell him stuff that Bovell could use in his campaign to bring accountability in his mind to the department.

Bovell: Yo, Campo dawg, you have the power. You have the opportunity, the capability to shut all this shit down. You are a duly sworn police officer sworn in to protect the people of your community and the United States of fucking America. Your jurisdiction is Mount Vernon, New York. You have due diligence to make the public aware of what the fuck is going on.

[music]

Kai: Coming up. We'll look at what impact these recordings had in Mount Vernon and what they've meant for residents like Alan Seward.

[music]

Kai: Hey, everybody. This year I spent a lot of February thinking seriously about Black History Month and why it leaves me kind of cold. I learned the cool origin story of the celebration. I hung out with people like Saidiya Hartman and Bernice McFadden and we even went to a Black history party. Anyway, we've gathered all of these shows together on our website in case you miss some of them, or if maybe you want to share the whole package with somebody, which I hope maybe you'll do because I think they're good conversation starters. Just go to wnyc.org/anxiety. You'll see a tab there labeled collections and when you click through on that, you'll find the series it's called the Future of Black History. Check it out. Thanks for listening.

[music]

Kai: When we left off this officer in Mount Vernon, Murashea Bovell, had started recording other officers as a way to prove what was happening there. What did those recordings ultimately reveal?

George: There are several officers that Bovell had known for years and was secretly recording.

Campo: What's up man.

Bovell: Oh, shit.

George: They're just straight-up talking about incidents of corruption and misconduct that they said they'd seen.

Bovell: Yo, what is with Antonini, man?

Campo: Because he's been beating motherfucker heads in, that's why. I can't stand him, man.

George: For example, John Campo, that officer we had talked about earlier.

Campo: What's going on Bovell?

Bovell: Yo, what's good?

George: He even prepared a list, which he gave to department leaders at the time.

Officer Campo: Whatever I tell you, you can't tell nobody?

Bovell: Yes.

Campo: Nobody knows, you can't mention it to anybody this conversation, nothing like that.

George: The list included everything from an officer assaulting someone in front of a supervisor.

Campo: I've seen brutality, false confessions, I see robberies.

George: An incident where he thought that his colleagues had planted drugs on someone in effect, framing them.

Campo: Illegally entering people's home and threatening them.

George: Strip searches without justification. Everything you could think of. He even mentioned this thing called the rainy-day fund.

Campo: I said illegal crack pipes and drugs are always on their person. They call it the rainy-day fund.

George: The implication being there, that officers were holding evidence on themselves, just in case they ever needed to use it, presumably for planting.

Campo: That's basically what I told them.

Bovell: Wow.

George: The officers themselves are painting a picture of an extremely corrupt unit that is making its own rules and deciding how to apply justice for themselves. This is the kind of stuff Alan Seward claims was happening to him.

Alan: All you got do is rub the wrong rat the wrong way, and they can throw you into a conspiracy case and fuck your whole world up and you didn't do absolutely nothing. Then if you can't prove your whereabouts, your alibi don't stick, you going to be in prison.

Kai: Then what did Bovell do with these recordings? Did they provide enough evidence that he was actually able to put an end to some of this stuff?

George: Bovell sent the recordings eventually to the West- District County, District attorney that's the local county prosecutors which he also happens to record.

D.A 1: I wanted to reach out to you. I'm in the public integrity bureau and-

George: Bovell and his attorney are hoping that they would launch an investigation.

Lawyer: Did you guys develop anything? Is there any merit to any of this?

D.A 2: The audios?

Lawyer: Yes.

D.A 2: The audios are very interesting yes. I went through them all. There's a lot in there. The Campo stuff.

George: But what we know based on some of his meetings with them-

D.A 1: You're telling us something that happened to someone else? There's only so much I can do with that.

George: Is that they say something to the effect of, "We haven’t moved forward on this. We tried calling you. We thought you weren't interested anymore."

D.A 2: I called you and eventually we closed it out.

George: "We closed the investigation."

D.A 1: If you want to go forward and you actually want to work with us regarding these types of things then that's a different story.

George: His lawyer is like, "Wait what? You're relying on us?"

Lawyer: The problem I'm having is--

George: You're the one that is now sitting on all of this evidence and you haven't done anything?

Lawyer: This is people staying in New York. You guys have an interest in rooting out corruption more than we do. It should be on your own that you're investigating this and calling these people in who are on the recordings and trying to decipher what's going on. I would think--

George: You've got to remember what Bovell was thinking in this moment. He's been waiting for months and months thinking that the DA is going to do something, but they didn't really do much of anything.

D.A: I'm not saying you're doing this, but recordings can be modified, they can be changed, you can delete parts of them, and you can do all these things. A recording on its own, it's hard to say but it's not--

George: The bottom line is these prosecutors, the very people who are tasked with overseeing the police were sitting on hours of tapes detailing numerous allegations of rampant corruption in this unit. In the meantime, while they had these tapes, they continued to push forward cases based on the word of the very officers who were the subject of these accusations in these recordings. The district attorney didn't mention these allegations at all to the very defendants. Most of them happened to be Black at least in Mount Vernon who were being charged based on the work of these officers.

Bovell: The process does not work. I followed the protocol to resolve these issues and it was swept under the carpet.

George: Bovell felt like he couldn't trust his department. He felt he couldn't trust his county prosecutors.

Bovell: You got to understand my mind said then, "I'm by myself. It's not like I have a master plan. Okay, if this doesn't work you do this, you do that, you do that." No. I'm terrified. I don't know what to do.

George: His attorney and him come to me, give me this trove of recordings and when I listen to them, I'm shocked. These are active-duty officers who are still on the force not knowing they're being recorded talking about all of this stuff.

Campo: He's done millions of things. Criminal acts. He's a criminal and you're allowing him to go to the county? I don't understand how that fucking works.

Kai: George, presumably had you not gotten these tapes and we had not started playing them on WNYC, no one would have known about these allegations in the first place, right? What impact has your reporting had on all this?

George: I was surprised but they came out at a very particular moment.

Reporter: You can see police here now firing tear gas into the crowd.

George: This is last summer at the height of the protest over the police killing of George Floyd.

Protester: We can't peacefully protest in these streets without getting tear gas thrown at us for what?

George: In that environment, a lot of people started to pay attention to it.

Speaker: I would like to introduce Westchester District Attorney candidate Mimi Rocah.

Speaker: For DA of West Chester county where she's taking on the incumbent Anthony Scarpino in the Democratic primary.

George: The local context is that there was a very intense primary fight for the Westchester County DA's race for the Democratic Party candidate. It was the incumbent verses a newcomer named Mimi Rocah a former federal prosecutor.

Mimi Rocah: I am running to be the next District Attorney in West Chester County where I live with my family right outside New York City.

George: When the stories came out, she really made this a campaign issue.

Mimi: The public needs to have faith in these very serious cases and investigations. That's the only way--

George: She was like, "This is not how a responsible DA is supposed to act. You're supposed to investigate this stuff. You're supposed to disclose this stuff. You can't just bury it and keep prosecuting people without telling them."

Mimi: The Vernon Westchester DA was given recordings that brings credible allegations about police corruption and brutality right here in Westchester County in Mount Vernon.

George: Since then, Mimi Rocah won the race handily and she's actively pursuing this investigation.

Mimi: That is the only way we can move forward as a community, as a country in this time.

Kai: What about this officer you described earlier, Camilo Antonini. What happened to him?

George: Right now, Detective Antonini has been put on desk duty, so he's still collecting a paycheck but he's not on the street doing the kind of narcotics work that he was years ago. Other officers, the department has said are no longer on the street doing plain clothes activities, driving around in unmarked cars. John Campo one of the officers that Bovell recorded a lot was suspended without pay. What role he plays in a potential investigation if anything, has yet to be determined.

Kai: Antonini and these other officers, how did they respond to these allegations? Have you managed to talk to any of them, or get a response from the police department in general?

George: The department has long maintained that they are investigating these allegations. In terms of individual officers for the most part they have either not responded or declined to comment on the record. In a few cases told us that they weren't involved in wrongdoing or that we're getting the story wrong but nothing very specific on the record.

Kai: The bigger question here is this special narcotics unit in the first place, I mean that's the structural problem. Is that these units are so often responsible for this kind of damage in Black communities, in brown communities all over the country. What happened to that unit in Mount Vernon?

George: After our series came out the department eventually announced that they had disbanded that unit. But the thing is they created another called the violent crime unit, which is not exactly the same, but it does have some of the same enforcement elements like plainclothes officers. When you talk to residents who have criminal histories in Mount Vernon, what they'll often say is, "I copped out. I took a plea because who's going to believe me verse the word of an officer? Someone with a badge."

That dynamic to some degree has changed in Mount Vernon because these tapes featuring officers themselves talking about police misconduct are now out there. There's many people in Mount Vernon and Westchester County, especially Black residents, who have come out of the woodwork and are now taking legal action. Whether that be seeking expungements of their convictions or filing lawsuits to get compensation for the harms that they say were done to them by this unit. Alan Seward is one of them.

Alan: This time I see a light at the end of the tunnel, so this is why I feel better putting the gloves on, on this too.

Speaker: People get railroaded all the time you know what I'm saying? It's just sometimes you've got to stand for something, or you can always fall for anything.

Kai: George, thank you for sharing all of this reporting with us.

George: Well, thank you, Kai. I appreciate it.

[music]

Kai: United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Joe Plourde mixed the podcast version. Matthew Marando was at the boards for the live show. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams. A special thanks this week for a bunch of extra work, thanks to Jami Floyd the editor of WNYC's Race and Justice Unit, and to engineers Bill Moss and Wayne Schulmister. Also, thanks to Celia Muller for such careful legal review of our recording and to our own Christopher Werth for producing this episode.

Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Karen Frillmann is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter at Kai_Wright and of course, as always, I hope you'll join us for the live version of the show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it at wnyc.org or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening, take care of yourselves.

[music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.