A Secret Meeting in South Bend

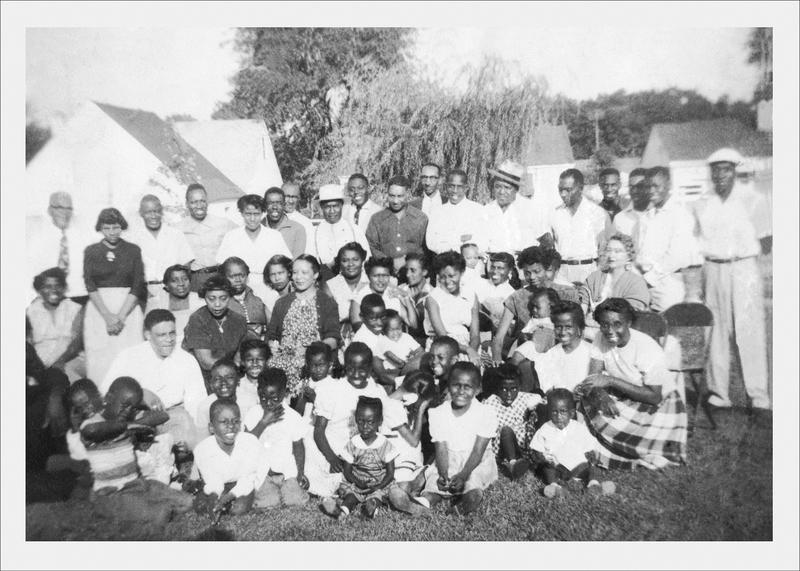

( Photo by Leroy Cobb courtesy of Gabrielle Robinson )

PREROLL

KAI WRIGHT: Hey everybody. We’ve been asking you about your anxieties — because we know they shape your politics. What are you carrying into the polls that surprises you in 2020? Here’s what Olivia from New Jersey told us.

OLIVIA: I never thought my generation (millennials) would have to adapt to a childless, marriageless and apartment lifestyles because of the economy, and get ridiculed by previous generations for it.

KAI: Keep your anxieties coming. We may not be able to solve them for you, but we may make an episode to help understand them at least. And the more personal to you, the better. Just record a voice memo and email it to me at anxiety@wnyc.org. Thanks. I’m Kai Wright and this is the United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history, and its grip on our future.

[THEME SONG]

KAI: I grew up in Indiana, but raised by Southerners. My dad’s people came up from Alabama, through Ohio and the hills of Kentucky, before they landed in the Midwest. They were chasing manufacturing jobs — these new opportunities open to black workers because of World War Two. So I’m a proud child of what’s known as the Great Migration — an estimated six million black people who left the South when it became painfully obvious that the promises of the Civil War and equal rights for all — that none of that was gonna become true. And because that’s what I come from, I kinda relate to Michael Jackson.

MICHAEL JACKSON: My dad always said Mississippi was a great state to be from — away from is what he meant [laughs].

KAI: This Michael is from South Bend, Indiana. And, when we sent our reporter, Jenny Casas to the heartland for this election season, she came back with this story about his family’s migration.

JENNY CASAS: As you can tell, he doesn't really feel that attached to the South.

KAI: Well by the way, Mississippi is where I was back in episode one, with the Lester family, who made the choice to stay in the South rather than migrate North.

JENNY: Mmmm. Yeah, I mean, I think in so many ways they're like- his- his parents are the opposite story. Right? Like they leave. They come up north.

KAI: Right-

JENNY: To like start this life together. And that's why Michael Jackson is like South Bend forever. He has like a lot of good memories.

[Sound of doors opening and closing]

MICHAEL: Cheerios?

JENNY: Mike Jackson would tell you that his heart is in South Bend.

JENNY: No I’m okay.

MICHAEL: You sure?

JENNY: It's always been in South Bend.

JENNY: How are you?

MICHAEL: Okay

JENNY: And I really got to see that when we drove around.

MICHAEL: Do you see that train going across?

JENNY: Yeah.

MICHAEL: Do you hear it? Listen to it. We used to come eat hamburgers right here at Toasties. Every time we were here the train’s going by and we’re eating these wonderful hamburgers. Yeah, Mom and dad and the three of us — five of us, the Jackson Five.

KAI: All right, so he’s a South Bend resident.

JENNY: So he doesn’t live in the city. He’s in the suburbs in this house that he has on a golf course in a suburb-

KAI: Okay [laughs]

JENNY: -called Granger.

MICHAEL: People in town or whatever say ‘Oh, you live out in Granger?’ It- it- you know, this was kind of like the ultimate place to end up.

JENNY: Why?

MICHAEL: Economically. Kind of you made it kind of deal.

JENNY: Ah-

MICHAEL: Granger.

JENNY: And so when people say, ‘oh, you live in Granger?’ What does that mean?

MICHAEL: That means, ‘oh, you must live in a big house with a swimming pool.’

JENNY: Which you do.

Michael: Which I do [laughs].

KAI: That comfort — at least, material comfort — it’s kind of his inheritance. Mine too. I mean, I don’t have the pool and all that stuff but, for me, and for Michael, and for millions of black people who grew up in the industrial Midwest, our parents and grandparents made a space for us, in what had been a very white world. In this season of our show, we’re trying to understand the history behind some of the most intense debates in this election, and we’re thinking about why this country is still struggling to become a multiracial democracy. That means going all the way back to the era just after the Civil War, a period called Reconstruction, when the U.S. first decided to be a interracial society. And maybe it’s because my mind’s in that space, thinking about the time when this country literally expanded the definition of “American.” Maybe that’s why I’ve become particularly sensitive about a rhetorical device that national politicians use: this implication that Midwestern places, places like where I grew up, are somehow the most authentically American communities. They talk about the ‘heartland.’ And a lot of the time, what they really mean is white people.

PETE BUTTIGIEG : Here’s how we’re going to win. We're going to force this president to stand on that debate stage, next to somebody who actually lives in a middle class neighborhood, in the industrial Midwest...

KAI: But Pete BUTTIGIEG is not the only one talking about the so-called heartland...

AMY KLOBUCHAR: America's great river, running straight through the middle of our country, through the heartland.

KAI: And of course, so much of our political debate in the Trump era has centered on the idea that someone needs to stand up for the forgotten “rustbelt.”

DONALD TRUMP: For years you watched as your politicians apologized for America. Now you have a president who is standing up for America, and we are standing up for you the people...

KAI: And it irks me because, it feels like it erases a whole other midwestern experience — families like mine and Michael Jackson’s and the people of the Great Migration, who also helped create the prosperity of the 20th century manufacturing boom. And they did it in spite of a whole set of rules and laws intended to leave them out of that prosperity. Here’s what you gotta understand: The Great Migration was, at least in part, a result of the fact that the country gave up on Reconstruction. Even though black people and abolitionists had won these incredible political victories, Congress didn’t have the last say. The Supreme Court did. And it stepped in and said: ‘nope.’

ERIC FONER: You see a graphic illustration of what can happen to your rights in the hands of a conservative Supreme Court.

KAI: Historian Eric Foner, who’s most recent book, The Second Founding details this history, says the Supreme Court turned the 14th Amendment into a dead letter. We’ve talked about the 14th Amendment in a previous episode: It’s the Constitutional amendment that established the idea of equal rights. But Congress still had to pass laws enforcing those rights, and that’s where the Court stepped in. First, there was a big ruling that said the amendment applied only to state governments. Private actors, they could do whatever they want:

FONER: So that was a serious blow to federal efforts to protect the rights day to day of African Americans.

KAI: And so white businesses created whites-only train cars, refused to sell black people everything from a home to a cup of coffee, you name it. All the stuff that we understand now as segregation. But that still wasn’t the all-encompassing regime that Jim Crow became in the 20th century.

FONER: The step to Jim Crow is a further step. Most famously Plessy V. Ferguson, because that's about state laws.

KAI: Plessy V. Ferguson. Now, Plessy’s the case you probably know about. It’s the infamous decision that state laws can mandate segregation, because separate can in fact be equal. The legal system we came to know as Jim Crow. And it spread all over the country, including to the Midwestern heartland, where white people policed it just as violently as they did in the South.

[Sounds of the angry crowd at the 1966 Housing March in Chicago]

KAI: Which is what Martin Luther King learned when he came north to Chicago, in 1966, and brought thousands of people into the streets to protest segregated housing.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: I can say that I have never seen — even in Mississippi and Alabama — mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I've seen here in Chicago.

KAI: They threw bricks and bottles. Someone hit King in the head with a rock, because they wanted to keep their neighborhoods closed.

KING: Oh yes, it’s definitely a closed society, and we’re gonna make it an open society. And we feel that we have to do it this way, in order to bring the evil out into the open, so that this community will be forced to deal with it.

KAI: But while King and the marchers were out in the streets a lot of black families — like Micheal’s, like mine — were fighting in another way. So in this episode, reporter Jenny Casas is gonna tell the story of how 26 black families tried to open a closed society. Tried to get a white neighborhood to share their heartland.

MICHAEL: They wanted the best for their family. So, they weren't rebels, but they were bound and determined to get what they wanted.

KAI: What happened back then? And what’s left of it? The story begins, like many things in the industrial Midwest, in a car…

JENNY: Okay, do you mind if I sit in the back?

MARIA : Oh- Okay yeah.

JENNY: When I first started reporting in South Bend-

JACOB TITUS: So I don't normally drive Maria’s car-

JENNY: I went on a lot of driving tours.

JENNY: And so- what- are we going this way? Where is your car?

JIM WOODS: Right over here.

JENNY: Every tour is different —

DIANA HESS: I'm going to pull over again [laughter]

JENNY: But all of them inevitably have three things; First — something related to Pete Buttigieg — like where he grew up or a place where my guide saw him in person.

DIANA: We went to the Chico's after,

JENNY: Oh right-

DIANA: After the parade and Pete came. Ugh, then there were groupies coming in, right? [Laughs]

JENNY: Second-

DIANA: There’s a vacant lot.

JENNY: Whether we’re in a neighborhood that has seen better days-

DIANA: another vacant lot, [laughter] another vacant lot.

JENNY: Or driving down a street, lined with historic mansions,

DIANA: The homes we just drove past…

JENNY: The contrast, the economic and racial segregation, it makes everyone bring up two city blocks of sort of matching single family homes. People know them as the “better homes” — Better Homes of South Bend.

JACOB: That's where they were.

JENNY: The people who put those houses on those two city blocks — they were fighters, but in a quiet and patient way. Not protesting in the streets, but — in crowded living rooms, and law offices, and bank board rooms. And at one point, with the help of an olympic gold medalist in a suit. And that story starts at the third place that every driving tour in South Bend has.

[Door closes]

JENNY: A visit to this giant empty field.

MICHAEL: And this, over here was Studebakers, it’s a vast field now. But just imagine, as far as you can see-

JENNY: There used to be a huge factory. The factory that Mike Jackson's father moved to South Bend to work in.

MICHAEL: As far as you can see up to that building and beyond, Studebakers. And you know it’s belching smoke and its piles of coal.

STUDEBAKER ADVERTISEMENT: Big news, big new, big new Studebaker. Craftsmanship with a flair.

JENNY: If Pete Buttigieg is why the country knows about South Bend today — it was Studebaker that put it on the map in the ‘40s and ‘50s. Studebakers were iconic cars, way ahead of the style curve with tough names like The President and The Commander. Heroes in movies and TV shows drove them, celebrities like Zsa Zsa Gabor advertised for them. People were flooding into South Bend to work in the factories — they were making cars and also tanks and engines for World War Two. Mike’s father started work in the foundry.

MICHAEL: Now my mom was a stay at home mom, and she would bring him his lunch pail and all that stuff...

JENNY: It’s where they made all the metal car parts. This was one of the most dangerous jobs in the factory because it required handling liquid metal, all day.

MICHAEL: A lot of times the minorities or the black guys that worked at Studebaker had to work in the foundry because it was the dirtiest, hottest, horrible-ist job in the factory.

JENNY: And Mike’s family lived right across the street from the foundry with other black factory workers. It was one of the only places in the city where black residents could live. Their houses resembled army barracks and they were built fast to house the Studebaker employees.

JENNY: Were there things about South Bend that you just loved?

NOLA: No. [laughs]

JENNY: [Laughs]

NOLA: In answer to your question, no [laughs].

JENNY: I called up Nola Allen because she, like Mike Jackson, grew up in this neighborhood.

NOLA: And it was such a- a close knit society. Everybody knew everybody else. Let's put it like that.

JENNY: She doesn’t live in South Bend anymore, she’s a retired lawyer and professor in South Florida. But she remembers the families worshipped together at church every Sunday, they shopped at the black business district nearby, and they grew food together in a community garden.

NOLA: It was the old- the old idea of a village. You better not get out of line because everybody knew who you were [laughs].

JENNY: Living in that neighborhood was loud and smokey and definitely a health hazard. Nobody wanted to make their lives there. And these families were starting to have kids and thinking about the future. They wanted and they knew they deserved something better.

NOLA: Well my parents, my parents needed a place to live, the question was how could they achieve that?

JENNY: At the time, a black family looking to buy property had very few choices. For example, black residents were welcome to buy land in a neighborhood called “The Lake.” Factories were dumping hazardous waste there and today it’s a superfund site. So absent moving next to a noxious dump — the families would have to come up with a plan. They needed a radical idea.

NOLA:Somehow or another, the idea was given to my parents. And they picked up the ball and proceeded to run with it.

JENNY: The story goes that Nola’s parents were playing bridge with a black attorney named J. Chester Allen. He and his wife were a South Bend power couple, J. Chester was the first black member of the South Bend City Council. And his wife Elizabeth was the first black woman attorney in Indiana. The Allen’s did own their home — in a white neighborhood near Notre Dame. They were both lawyers, people with the means and the know how to buy a house — but even they had to jump through hoops to get their home. And somewhere in that house hunting process, something clicked for J.Chester Allen: Realtors and banks would turn down individual black families, because they knew they were black. But it would be a lot harder to turn down a sale if the buyer was a company. So, over the bridge game, J. Chester Allen told Nola’s parents: there is power in numbers. If you want to buy in a different neighborhood — start a company. A cooperative. So they started with a name.

NOLA: My mother is a devotee of the magazine, Better Homes and Gardens [laughs]. So I am certain that that's where she got the idea of calling it Better Homes.

JENNY: Now, they needed people. And that wasn’t a problem because everyone knew everyone. Nola’s mom was talking to people at church, her dad was finding people at work — and before long they had a critical mass. 26 families came to their first meeting. A secret meeting.

GABRIELLE ROBINSON: This is, you know, that famous beginning of it —

JENNY: Gabrielle Robinson is a German transplant to South Bend, and the author of a book about Better Homes. And she has copies of all the meeting minutes.

GABRIELLE: May 21st, 1950, a nonprofit organization was formed and given the name Better Homes of South Bend Inc. And it says a contract was read by lawyer Chester Allen. And a likely prospect was mentioned by him as a beautiful site for building. This was the secret site that they would never even mention in the minutes. It seems so simple and so plain. But I can just see how much hope and fear and courage lay behind this simple statement.

JENNY: We can only really practice courage when we’re afraid, and the Better Homes families had plenty to be afraid of. I found this transcript that will give you an idea of what it was like. It was from a hearing on housing discrimination held by two Notre Dame professors — it’s around the time Better Homes was trying to pull off this land purchase. And at the hearing, black South Benders testified one by one about the racism they faced while trying to find a home. White realtors and home owners told them flat out they would not sell to black families. And they said it in every offensive way that you can imagine. When one black family did manage to buy in a white neighborhood, a cross was burned on their lawn. And white homeowners who wanted to sell to black families, they were also threatened by their neighbors. It’s wild the violence white people were willing to inflict on each other to keep their neighborhoods white: physical threats delivered by letters and late night phone calls, leaving “obscene objects” on porches, throwing rocks through windows and at the family’s children, throwing paint, filing false criminal charges, and even petitioning to have a homeowner committed to a psychiatric ward by force. You can see why the 26 families of Better Homes met in secret. The land they wanted to buy was on the undeveloped edge of a white neighborhood. That’s why it was dangerous.

NOLA: They were aware that others did not want them to succeed. So, no, there was not a whole lot of talk about what they did outside of the group, even within the group.

JENNY: But Better Homes was saving their money so they could afford to get these houses built. J. Chester Allen sealed the deal with the state so the group was officially incorporated. And a few weeks later with the help of a white lawyer, their corporation managed to buy the land. And together the 26 families became the proud owners of the 1700 and 1800 blocks of North Elmer St. But that was just the first step.

ADRIENNE COLLIER: Mmmm okay, we are interviewing Mr. and Mrs. Cobb…

JENNY: There’s an Oral History Collection at the Civil Rights Heritage Center out of Indiana University. And they have an interview with the youngest members of Better Homes, Margaret and Leroy Cobb. It gives you a sense of the kind of troubles the families faced, even after they had the land.

LEROY COBB: At that time we encountered so much problem about having a home built.

JENNY: There were no sewer lines and there were no sidewalks.

LEROY: We had a heck of a time trying to find a contractor to build for us.

JENNY: Three separate contractors gave the Better Homes families the run around. The first wouldn’t stick to a price, one wanted to use substandard building materials, and another wouldn’t follow the blueprints. And all 26 families were still living near the Studebaker factory. They were attending meetings after long hours of pouring metal, and they’re just throwing money, two and three hundred dollars at a time, into these systems that they don’t know, and that aren’t yielding immediate results.

NOLA: These were people who were not college educated and had not really had any real involvement with city and county or state government. Most of it was legal gobbledygook to them [laughs]. All they knew was they wanted a house and this was a way for them to get a house.

JENNY: They were risking head and heart for something that wasn’t guaranteed to work out. And then, the group gets a reminder that what they were doing could have violent consequences.

DAVID HEALEY: They sent you threatening letters?

LEROY: Oh yes-

MARGARET: To our lawyer. You don’t even want to know what the letter said.

JENNY: Just a warning, the tape I’m about to play you has a racial slur in it.

HEALEY: I was going to ask you, did they save a copy of it? Is there a copy of it anywhere?

LEROY: Tell them what it said, what the letter said.

MARGARET: We had meetings every month, and he brought the letter and he said ‘I’m going to read the people this letter because we are having problems.’ He said, ‘this is the letter from the community out there.’ I don’t- It wasn’t signed.

LEROY: Oh no, it definitely wasn’t signed.

MARGARET: It just said, “You ni****s better stay in your place.” That’s exactly what it said. I was telling my husband about that this morning. I remember it just like it was this morning.

JENNY: Six of the original families drop out. Two new ones take their place, and all the while, J. Chester Allen is managing Better Homes basically for free. He’s the only one who knows anything about how to make this idea work. While he was spending endless hours helping the families with the mountains of paperwork, his wife was picking up the slack at their joint law practice.

NOLA: You know this went on for years. You can understand why she would be upset that her law partner [laughs] and husband was doing all of this public service.

GABRIELLE: And then, of course, the biggest hurdle were the banks.

JENNY: Everything was finally in place, but now they couldn’t get the loans to build the actual structures.

GABRIELLE: Banks just wouldn't lend to African-Americans for homes. And certainly not for homes in a white area. So, you know, even today, it's still harder for African-Americans to get a mortgage than it is for whites. But then it was almost impossible.

JENNY: And this is the part of the story where the Olympian steps up. He’s this guy who worked for the Federal Housing Administration as ‘a race relations advisor.’ He lived four hours away.

LEROY: We actually had to go to the FHA, the district office, which was in Cleveland, Ohio at that time. And the fellow they sent here was a black fellow named DeHart Hubbard.

JENNY: DeHart Hubbard, was the first black American athlete to win a gold medal in an individual Olympic event. The Federal Housing Administration was fueling the housing boom across the country by backing mortgages for mostly white families who wanted to buy. And DeHart Hubbard was working on the inside to make those systems work for black homeowners. Leroy remembers sitting in the fancy boardrooms overlooking the city, watching this olympian go toe to toe with the South Bend bank executives. DeHart Hubbard could do it because he was with the federal government.

LEROY: He said, “You know, we have federal money that's deposited in the banks every month.”

JENNY: He told them the Better Homes families have impeccable credit.

LEROY: But yet you are going to discriminate against them because you are saying you don’t want to finance these homes. But yet you would turn right around and finance them a car.

JENNY: Finally the argument that Better Homes money was as good as anyone else’s won out — and a handful of banks agreed to split up the loans across the remaining 22 families.

MICHAEL: You know, there was wood everywhere and it smelled good and it looked way bigger than what we were living in and things like that. To me it was like a castle, but it was a three bedroom house. You know, but to me, it was like, ‘wow.’ And so it was really different. Even as a little kid. I could tell how different it was.

JENNY:Mike Jackson’s family home was the first one built on the block.

MICHAEL: We should go to Elmer Street now, really, because it's on the way home, I can make it on the way home.

JENNY: And when we drive out there together, past the vacant lot where his neighbor’s house used to be, past the little hill where the kids used to sled, the memories are as thick as January molasses.

MICHAEL: We used to race, ah-ha, here we go. We would race all the way to the cemetery down here. And back. And I always won. *laughs*

JENNY: He can name all the kids that used to live in each of the houses.

MICHAEL: This was Rosie Warfield’s house. I say it like that because Rosie was cute.

JENNY: He remembers the games they played, who’s basement he had his first beer in.

MICHAEL: You know who he was like? He was like Eddie Hascal in Leave it to Beaver. He was a real wise guy but a real polite when he was around the grownups.

MICHAEL: And when we pull up in front of his old family home.

MICHAEL: [Sounds of walking over dead leaves] I don’t even know who lives next door.

JENNY: It’s a modest wood frame structure. The paint is faded white with dark green trim. And it’s only about 40 degrees out, but standing there brings back spring, and the lawn and Mike’s parents in the garden.

MICHAEL: This was all flowers. Flower beds and black dirt, and she’s out here, mom’s working in the flowers and dad’s just got the yard just cut like a baseball field, all the way to the back No weeds. All baseball field. Picture that. Just perfect. Or close to it, perfect to us. [Door shuts] You know, it was just so pretty, we were always proud of our house. But it’s not my house anymore. I really kinda don’t look at it like my house anymore. It’s not that the house did anything- it did great things, but it’s not my house.

JENNY: It’s been almost 70 years since the Better Homes were first built and only a handful are still owned by the original families. It took so much to make these homes a reality and the challenges never stopped.

COLLIER: So, once you moved out here, your area was, on Elmer Street was primarily made up of black families?

LEROY: No, no. Now, when you say that, just the 1700 and 1800 block. Everything else was white. That was it. Right. Just those two blocks. Right.

HEALEY: So, you had two blocks in the middle of a white neighborhood?

LEROY: Right. Right. Right.

HEALEY: What kind of problems did that cause?

MARGARET: All kinds. All kinds.

JENNY: The year that Mike’s family moved onto North Elmer, he and his peers were the first black students to go to the local schools. Margaret and Leroy Cobb’s son told me that on the first day of school, he thought the local families threw a parade for him and the other kids. And he found out years later that it was a protest.

MICHAEL: ...gathered and talked about growing up on Elmer St.

JENNY: And it wasn’t just in school. Mike and some of his childhood friends told me about the neighborhood little league.

MICHAEL: They built a brand new little league park. They had uniforms, they had hats, they had teams they had managers they had all this new equipment, and so we’re going to join the little league then because here comes real baseball. We come to find out that the boundaries stopped at like O’Brien Street, we were the last blocks of population, but they still stopped the boundaries right before where we lived so we couldn’t play in the little league.

JENNY: In late 1963, a decade after the Better Homes were built, the Studebaker plant in South Bend closed. Everyone lost their jobs.

MICHAEL: You know, they laid off my dad. You went to work, laid him off. You went to work. They laid him off, you know, and eventually he had to- they- they closed the left South Bend.

And the families still had mortgages to pay.

BUTTIGIEG: And think of what it must have been like in 1963 when the great Studebaker auto company collapsed and the shock brought our city to its knees.

JENNY: There may be no moment in South Bend history that looms larger than the closure of the Studebaker factory. Mayor Pete launched his presidential campaign in an old Studebaker building.

BUTTIGIEG: Buildings like this one fell quiet, and acres of land around us slowly became a rust-scape of industrial decline.

MICHAEL: I'm wondering, are we going to be OK? Are we still gonna have this Elmer Street house with all these good food and all this stuff?

JENNY: If you tick through what happened to each one of the Better Homes of South Bend families — they were by a lot of standards, ok. A lot of them found other jobs, some lived out their lives in their better homes, some moved out of South Bend, some stayed but moved to bigger houses. But with the loss of jobs and industry almost, every neighborhood in the city changed, including theirs. So when Mike says it’s not my house any more, he doesn’t mean literally. He still owns the house. He just doesn’t want it anymore.

MICHAEL: It was never a plan to save it for upcoming Jackson’s. So there’s nobody who would come back and live there.

JENNY: And you wouldn’t want them to?

MICHAEL: No, that’d be like a step down in a way. I could pour money into it right now and make it great. I’m not going to do that. It’s in a high crime area that’s going down in value. It’s like taking your money and instead of putting it in a savings account, you just throw it on the bank steps and walk away. It doesn’t make sense.

Kai: Coming up, we face a cold economic calculation: the monetary value today of the homes the Great Migration built.

MIDROLL

KAI: If you’ve never seen the painter Jacob Lawerence’s migration series, I urge you to look it up. It’s 60 panels, depicting the Great Migration in these rich, brooding colors and hard, angular shapes. It was Lawrence’s real time effort to document the contradictions of this remarkable event. My dad was into Lawrence and I guess his paintings were among the many little ways my dad passed on a reverence for this generation of black people to me. So it’s hard for me to hear Mike Jackson look at his parents’ home, look at what they worked so hard to build, and conclude, this isn’t worth keeping. But also I get it. I mean, I own part of my grandmother’s old house in Indianapolis, and I too am not sure why we keep it. I know there’s a lot of people like us.

JENNY: Okay, can I get your full name? How you might introduce yourself at a party?

KAI: Like, when Jenny went to talk to South Bend’s Director of Economic Empowerment-

ALKEYNA ALDRIDGE: My name is Alkeyna Aldridge.

KAI: She stumbled into another personal story like mine.

ALKEYNA: I would describe myself at a party...Oh…

KAI: Another one of us who’s questioning the value of a family home.

ALKEYNA: It's so interesting because I grew up in this town and it's so segregated.

KAI: This is just a minute or two into the interview, and already the conversation turns to where she grew up and why.

JENNY: How long has your family been in South Bend?

ALKEYNA: My family came from Brownsville Tennessee. My great grandmother, she worked at Studebaker. Rosie Riveter of Studebaker, at least how I think of her.

KAI: Alkeyna grew up on the west side in LaSalle Park, the neighborhood people call The Lake — That’s the redlined area of South Bend that the Better Homes families didn’t want to move to because of the industrial dumping there. You’ll remember it’s now a super fund site. But back then, her family built a house there. And like the Better Homes families — they also had to fight for basic infrastructure in the neighborhood when they moved in.

ALKEYNA: And we like, had a two bedroom home with like family of 10 in it until we could build a larger one. And my uncles and their father built a larger one. And my great grandmother had a great retirement. And like, you know, that was their moment in the sun.

KAI: But that was their moment — and she’s not sure she’ll have hers. Her family worked hard to create some generational wealth. And yet…

ALKEYNA: I think my great grandmother like, had more wealth than I do at this point. And I'm like, graduated from the University of Notre Dame. And she was Rosie the Riveter in Studebaker factory. And like, what does that say about opportunity for African-Americans in this community or anyone?

KAI: Alkeyna says now that she’s working in City Hall, she meets people from South Bend, from her graduating class at Notre Dame — that she’s never met before. Because like she said, their lives are so segregated.

ALKEYNA: We should have been friends our whole life. Why am I just meeting you? You live like five miles away.

KAI: Her job at City Hall is to try to bring public money to neighborhoods like the one she grew up in.

ALKEYNA: And so, yeah, it's- I describe myself as a bridge builder. Between communities and just trying to break down those barriers.

KAI: But in her personal life, she’s confronting the same reality as Mike Jackson is. Alkeyna’s family’s story is different from his in fundamental ways, but they arrive at the same place:

ALKEYNA: What I think is a real tragedy and speaks to the kind of people doing everything they can to, you know, reach that American dream. And like you are given this land that's worthless and that's even more worthless now than it was 40 years ago. And uhm, we'll keep the house for sentimental value. But I'm not sure that it's going to be worth what my great uncle thought he was building for his sons and grandchildren. There is no dollar amount that I think you can put on the hope that perhaps my great uncle felt building that home with his sons. That will potentially become a burden to them. You can't put a dollar amount on those lost hopes.

KAI: There is actually some recent research that has tried to do just that — put a dollar amount on lost hopes and dreams. Everyone living in South Bend has had to face the challenges of a city still defined by the loss of industry. But, the neighborhoods where Alkeyna and Michael’s family homes stand are majority black. The Lake always was. The Better Homes area, where Michael grew up, it became a black neighborhood. And last year, the Brookings Institute published a study that says, just flat-out, this one fact: an address in a black neighborhood makes those homes less valuable.

KAI: Hey, is this Andre?

KAI: I called this study’s lead author, Andre Perry.

ANDRE: Hey how are you?

KAI: And I asked him to walk me through the findings.

KAI: How did you isolate race and racism in this?

ANDRE: Well you know-

KAI: First they had to control for all the stuff that might be at play other than race.

ANDRE: Statistically, we accounted for crime and education and walkability and all those fancy Zillow metrics.

KAI: And even with these controls, they found a square foot of residential housing in a majority black neighborhood is worth 23 percent less than the same square foot in a neighborhood with few or no black people.

ANDRE: And cumulatively that amounts to about 156 billion dollars of what amounts to lost equity.

Kai: 156 billion dollars.

ANDRE: And there's this, there's this narrative out there that the condition of black cities are a result of individual choices of its residents. No, we have strong assets in black America and black neighborhoods. They are just devalued-

KAI: I want to clarify that we're not talking about necessarily, you know, an individual black homeowner in a largely white neighborhood, and look, that person is suffering a racist result. It's really about the concentration of race? And so it's really about segregation that we're talking about.

ANDRE: Well, there's an interesting chart in the devaluation report and you see how home prices go down or up based on the concentration of blackness. So as the concentration of black people increase, the housing prices decline. So, you know, there is a sweet spot in there [laughs].

Kai: Where you have just enough blackness not to be a problem.

ANDRE: Exactly. Yeah- you know, what's interesting, when I present the data all across the country, people lose sight of that, even white people in black neighborhoods, their homes are devalued.

KAI: Right.

ANDRE: And so, yes, this is a, this is an American tragedy.

And we know that that money would- would have gone to send someone to college, to support a small business. It would have funded education and you know, we're talking about people who are doing everything that they've been told is required to achieve the American dream. And they're not reaping the equity based on those efforts.

KAI: So you’ve been in these conversations with policy makers. Uh, last summer you testified before the sub-committee on housing and community development. Can you recall that testimony? What was striking about that?

ANDRE: [laughs] Oh man it’s hilarious. Al Green asked myself and members of the appraisal community, the appraisal lobby, whether or not we believe discrimination exists. And he asked us to raise our hand. I was the only one that raised their hand! And again what’s astounding about that is if there’s one thing we have clear evidence on discrimination, it’s housing policy. But after this hearing the number of appraisers that came up to me — ‘I’m not discriminating, I’m not racist, there’s rules against that. I don’t do anything wrong.’ Well remember that for most of American history it was legal to segregate. And those practices that were created during that period, they’re still with us today.

KAI: You can draw a line from what Andre’s talking about, back 120 some-odd years, to the Supreme Court ruling — Plessy v. Ferguson — the one that said ‘segregation is legal.’ That ruling not only put an end to any last vestige of Reconstruction, it also set up decades of perfectly legal racial discrimination in both state and federal economic policies.

ANDRE: You know, I’d like to say it plainly, we cut a check to white Americans and we didn't cut one to black Americans. And I bring up the past for this reason: We've been down this road before, where white communities were struggling and the federal government found a way to solve the problem, essentially by making sure folks could purchase a home. They invested in transportation policy, essentially helped facilitate the creation of the suburbs.

KAI: This is all the New Deal between the 30s and the end of World War Two, that we're talking about.

ANDRE: That's exactly right. So we had a number of programs, initiatives, that supported the economic mobility of struggling whites. And it was successful. So whites were able to accrue wealth; blacks were not. We need to figure out ways to get more capital to folks who've been denied it historically. And that's that's the point.

KAI: Gosh, it feels like such a recurring cycle. I mean, this was the conversation like way back in the 80s even, right? That oh, there’s no capital, so you need to lend money in black neighborhoods — but then those loans were debt traps. And then now it's like, no, no, you can't do that. And so there's no capital. It just goes round and round.

ANDRE: But what goes round around is the racism. When you devalue people, you never get the policy right. We still devalue black people. That's the issue, because we haven't found real policy solutions to the racism problem. We have not corrected for the racial housing discrimination that has always been a drag on the economy and the home buying market.

KAI: Andre is asking us to consider, what would places like South Bend be like today — economically, at least — what would the overall picture of the American economy look like, if black families had kept that $156 billion in wealth that we lost, because of racism? This is one of Jim Crow’s most lasting legacies; it was, and is a looong and expensive coda to Reconstruction. Andre Perry has a book called Know Your Price. And that title is inspired by an August Wilson play. The play centers on a character named Memphis Lee. He owns a diner in a black neighborhood of Pittsburgh that really grew out of segregation. And one day, white developers come along and they decide they wanna build an arena in the neighborhood, so they try to push Memphis out. A lot of tragedy follows, but in the end, Memphis stands his ground. He doesn’t budge until he gets a fair price for his property.

ANDRE: The moral of the story is that you have to know that you have worth. But more importantly, you have to know the information to stand on your price.

KAI: Well, and even if you've really been taught that you're not worth much. I mean, part of that play is that Memphis Lee’s diner is a bit of a ramshackle,

ANDRE: That’s right.

KAI: And he's the only one who knows it's worth something.

ANDRE: That's exactly right. And that's the story of the black America. We know that we have value, when other folks are devaluing our assets, both in terms of our person and our property. So it's important that we hold true to our value no matter what.

CREDITS

KAI: The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. This episode was reported and produced by Jenny Casas. Special thanks to the archivists at the oral history collection of the civil rights heritage center at Indiana University, South Bend. The episode was edited by Marianne McCune. Cayce Means is our technical director. Karen Frillman is our executive producer. Our team also includes Emily Botien, Jessica Miller, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams. With help this week from Michelle Harris, Isaac Jones, Bill Moss, and Kim Nowacki. Our theme music is written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Brand. And you can hit me up on twitter, @kai_wright. Thanks for listening.