New Hopes, Old Fears

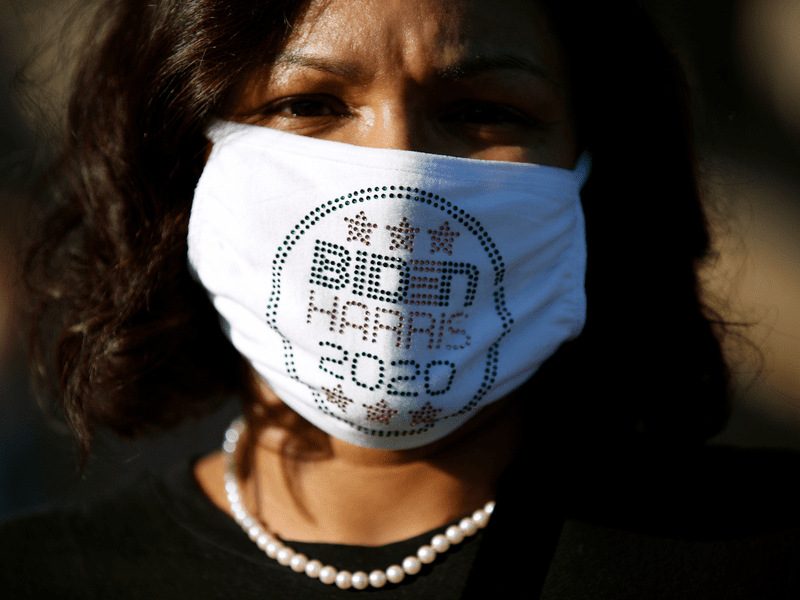

( AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell )

Kai Wright: This is the United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

Amanda Gorman: In this truth, in this faith, we trust. For while we have our eyes on the future, history has its eyes on us. This is the era of just redemption.

Vice President Kamala Harris: For many months, we have grieved by ourselves. Tonight, we grieve and begin healing together.

Keshia Chante: It's hard to get choked up watching it. It's so incredible, and I'm optimistic.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.: So help you God.

President Joe Biden: So help me God.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.: Congratulations Mr. President.

Tommy Vietor: I think America is relieved. Beating the final boss took a little longer than we'd hope, but Donald Trump is gone.

Vox Pop: It's going to get better, but it's not going to happen overnight.

President Joe Biden: “If my name ever goes down into history, it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.” My whole soul is in it.

Kai: I'm Kai Wright, welcome to the show. We're going to dedicate the show to making a transition together because we did, initially, create the United States of Anxiety in response to the 2016 presidential elections. That's the name. Plainly, Donald Trump has taken up so much space, emotionally, mentally, politically. In the wake of all that, I'm asking myself, "What have I been carrying around for the past five years that I can put down? Conversely, what do I need to hold on to?"

For instance, even Twitter, it really wasn't a thing in my life four years ago, but now, I tend to start my days in my Twitter feed, chasing the invariably bad news of the day, which I know is a really awful idea for a host of reasons, but there it is. I do it. To manage that, I've also packed my timeline with counterprogramming. One thing that happens routinely is a little snippet of a poem will pop up in my feed because someone will say, "Hey, stop this and go read a poem." Quite often, it's a Jericho Brown poem.

When I take the advice and step away from my computer and open one of his books, my whole body shifts to a healthier place. Jericho Brown won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2020, for his book, The Tradition, which is his third collection. Since his poetry has held my hand many a morning, I asked him to help convene the show today. Jericho, thank you so much for accepting that invitation.

Jericho Brown: Thank you so much, Kai, for saying that. I am stunned. I was sitting here with my mouth open. It's so kind. Thank you.

Kai: Oh, well-

Jericho: Thank you.

Kai: - you're a humble man.

Jericho: Thank you.

Kai: We've all been reminded of the power of words. Certainly, over the past four years, Donald Trump used language and these just word storms as his primary political weapons. Joe Biden is now explicitly trying to contrast himself through his own language and how he's used words. I wonder if you can just reflect on language over the past four years, just the words we've taken in and how they've affected us. As a person who specializes in the carefully chosen word, I wonder what that's been like for you.

Jericho: I think what's been most interesting to me is that we've probably gained a better idea that the word does indeed have power, in and of itself, that when you say a thing, when you write a thing down, you are more likely in a position to make that thing true. I think maybe before Donald Trump, people were a little bit glib about that knowledge, but no matter how much he might have later had to say that he was only joking, most of us knew when Donald Trump said something, he was going to do it. That culminated in that horrendous Wednesday event, the insurrection.

When I think about the power of the word, and I think about the uses of imagination, I hope that what we have learned is that we have just as much power over that as Donald Trump, that I have a way of building for myself the world I want to see. If you want to see a world of strife, then your words can make that happen, so the opposite must be possible, and that's what I try to do with my poems.

Kai: That's a lovely sentiment. What about the question I put to myself here at the beginning? For you, is there anything you've been carrying around that you feel like you can put down now?

Jericho: That's a great question. I do feel lighter. I must have- [crosstalk]

Kai: There's some baggage left.

Jericho: I will tell you this, I think it becomes easier to look at one's self or to look at one's close community when you're not busy facing some supposedly enemy, right? It's hard to take care of yours-- I want to live in a world where I thrive as opposed to living in a world where I feel like I survived. Those are two different ways of being. I'm really interested in thriving, and because I'm interested in thriving, I'm in a position where I'd rather not have to deal with the guy who used to be in the White House. It just feels better. [laughs]

Kai: Right. That's a really interesting idea that when you can actually stop and think about yourself, actually stop and think about where you want to go if you're not so busy thinking about where you don't want to go.

Jericho: There's also real fear if you have the sense that someone unstable is running the show. They have things like nuclear codes. That's real fear that even if we don't voice, we wake up and go to bed with every night. When you think, that's dangerous, and that's the stress many of us have literally been carrying around.

Kai: What about the inverse? Is there's something you've picked up, positive or negative, over these recent years that you want to hold on to as you move forward?

Jericho: I just think that I've learned a lot more that there really needs to be more platforms available for that, which is the supposedly radical left in this nation. It's so interesting to hear people call people like Reverend Warnock, my senator from Georgia, call people like that a radical. I'm thinking, "That's a radical? Wow."

Kai: What does that make me?

Jericho: Exactly. It seems, to me, that we have a better middle. Right now, I have a fear of what people in this nation call moderate. I don't think of that as the real middle. I know that in order to make something closer to a real middle happen, we need to have some people pushing a little bit farther left, and I feel like that's what I'm here for.

Kai: What do you think of this idea-- I know you said you were flattered by it, but this idea that your poetry for a lot of people has been counterprogramming over this time because when I see it, it's someone else has tweeted, has said, "Hey, you know what, you should go read this Jericho Brown poem." What do you think about that, the idea of poetry is counterprogramming to the news?

Jericho: That is wonderful because as I said before, I believe in that. I believe that poetry stops time, that poetry puts us in a position where we have no choice but to slow down. That poetry allows us to-- You're literally looking at ink on paper, and suddenly, you have images in your mind. Poetry gives us an opportunity to breathe a little more deeply, to save ourselves a little bit more through the day. I believe in that sentiment, and because I believe in it, I'm particularly grateful when somebody says that about me since that's all I ever wanted to do since I was 10 years old. It means the world to me.

Kai: You wrote a poem to mark the inauguration. It was published in the New York Times Online on Inauguration Day, and the other reason that I asked you here today is I'm hoping that you'll read that for us to start today's show.

Jericho: Yes, I'll read it. Here we go.

Inaugural.

We were told that it is dangerous to touch

And yet we journeyed here, where what we believe

Meets what must be done. You want to see, in spite

Of my mask, my face. We imagine, in time

Of disease, our grandmothers

Whole. We imagine an impossible

America and call one another

A fool for doing so. Grown up from the ground,

Thrown out of the sea, fallen from the sky,

No matter how we’ve come, we’ve come a mighty

Long way. If I touch any of you, if I

Shake one hand, I am nearer another

Beginning. Can’t you feel it? The trouble

With me is I’m just like you. I don’t want

To be hopeful if it means I’ve got to be

Naïve. I’ve bent so low in my hunger,

My hair’s already been in the soup,

And when I speak it’s just beneath my self-

Imposed halo. You’ll forgive me if you can

Forgive yourself. I forgive you as you build

A museum of weapons we soon visit

Just to see what we once were. I forgive us

Our debts. We were told to wake up grateful,

So we try to fall asleep that way. Where, then,

Shall we put our pains when we want rest?

I don’t carry a knife, but I understand

The desperation of those who do,

Which is why I am recounting the facts

As calmly as I can. The year is new,

And we mean to use our imaginations.

One of us wants to raise George Stinney

From the dead. One of us wants a small vial

Of the sweat left on Sylvia Rivera’s

Headband. Some want to be the music made

Magical by Bill Withers’s stutter.

Others come with maps and magnifying

Glasses and graphite pencils to find

Locations beside the mind where we are not

Patrolled or surveilled or corralled or chained.

I, myself, have come to reclaim the teeth

In George Washington’s mouth and plant them

In the backyards of big houses that are not

In my name. My cousins want to share

A single bale of the cotton our mothers

Picked as children. I would love to live

In a country that lets me grow old.

I long. I long for that. We are otherwise

Easily satisfied. Where do we get

Tangerines for cheap? Can we make it

There on the Metro? How hot is the fire

Fairy blister of chocolate chipotle sauce,

And will you judge me if I taste it? But now,

We’ve put our hunger down for the time it takes

To come and reconcile ourselves to the land

Because it is holy, to the water

Because it swallowed our ancestors,

To the air because we are dumb enough

To decide on something as difficult

As love. If no one’s punishment leads to

My salvation, then accountability

Is what waits. It moves citizens, mends nations.

That’s for us to prove. That’s the deed to witness.

That’s the single item on the agenda

Read in Braille or by eye, ink drying like blood

Spilled this American hour of our lives.

Kai: Jericho Brown's poem, Inaugural, was published in the New York Times Magazine. His collection, The Tradition, won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. Jericho, thank you so much for helping us inaugurate a new chapter of this show.

Jericho: Thank you, Kai.

Kai: We began with a poet, and now, we turn to a historian to think about sitting in the aftermath of great crimes. I'm Kai Wright. This is the United States of Anxiety. We'll be right back.

[music]

Welcome back. This is the United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wight. Like so many of you out there this week, I'm just trying to exhale to let out some of the anxiety, the fear, and the rage that I have held so tightly over the recent years, over, certainly, the past year, but I'm also thinking about what I cannot forget, what I have to hold onto, even as the national conversation turns to renewal.

I'm joined now by a historian who's made it her life's work to research the aftermath of anti-Black violence. Kidada Williams is a professor of African-American history at Wayne State University. She's the author of the book, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. She was one of the co-creators of a remarkable public history project that you may remember, it was called the Charleston Syllabus, and it was a resource list for public learning after the murders at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, in 2015. Dr. Williams, first off, thanks for joining us.

Kidada Williams: Thank you so much for having me.

Kai: I want to start-- I mentioned that Charleston Syllabus project because I do want to start there. It grew into a book that you also co-edited. Joe Biden, he says he decided to run for president again at this late stage in his career because he saw what happened at the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, two years after the murders in Charleston.

To a lot of people that event and the insurrection on January 6th of this year, they're just points in a timeline with Charleston, but your work with that syllabus, you're saying that all of these events are part of a much longer timeline of violence. I wonder what you would say to President Biden, who again, was motivated to his whole office by this violence in Charlottesville. I wonder what you would say to him he should know if repairing that is what he wants to do.

Kidada: I think that what I would say to the president is that he needs to make sure that he understands that we have a long history of this violence, dating back to slavery, coming forward clan strikes, and massacres and rampages during Reconstruction, lynching and assassinations during Jim Crow, and that this violence has left a significant impact on African-Americans and the rest of the nation.

Part of what happens is that we go through this cycle, there's the violence, there's the impunity, the laws often used as a shield against truth and justice, there are calls to quickly move forward and on healing without any real acknowledgment of the real harm that's done and no policy to stop it from happening again, and then, there's the eraser of what happened as the nation moves, and because the Americans have preferred the easy way out, the cycle repeats, and Black and brown people continue to suffer and die. What I would say to the president is that if he knows this history and he's determined to stop the cycle, then we need to have a real accounting for what has happened and we need real policy measures in order to stop it from happening again.

Kai: Yes. I don't know if you were able to hear my conversation with Jericho Brown before the break, but he read his poem that he wrote for the inauguration. There's a line in it, he says, "Where then shall we put our pains when we want rest?" That line really hits me. I'm thinking about it in relationship to your work because your book looks at these personal testimonies of people touched by anti-Black violence in the run-up to the Civil Rights Movement. I wonder if there's a particular story in that history that you'd want to share with us with that line in mind.

Kidada: I think I'll share the story of Gaynor Atkins. His son, Charlie Atkins, was killed by a mob in Georgia, in 1922, and he and his wife are brutalized and arrested shortly afterwards. I discover him in the historical record five years later, when Gaynor, the father, starts writing letters to the NAACP. He's trying to get something close to justice because he can't get his son back, but losing the son the way he did is weighing heavily on his heart. That's one of the realities that we see with African-Americans, especially if we look at the pain of the violence that's done to them.

Often, what happens is that we focus on the fact that violence happened. We think about it in the abstract, and we don't make time for or sit with what African-Americans say this violence has done to them. Gaynor's letters to the NAACP make that clear that he is aching, that he is anguished by losing his 13-year-old son in this way. He says in his letter to Walter White that he wants someone to help lift that burden.

He doesn't quite know for sure what that actually looks like, what will lift that burden, but he believes that something needs to be done preferably to stop this violence from happening. That line in the poem acknowledges the harms of whiteness and a commitment to white supremacy, and the fact that Black people often don't have the opportunity to deal with the reality of what has happened to them and to have it acknowledged by the larger society.

Kai: I wonder about you doing this work. The big question I'm asking throughout this show as I'm thinking for myself about what I want to put down. I want to put that kind of pain down. I'll be honest, that's something I just don't want to stare at anymore, and you have made it your work to call us into staring into it. I guess for you, personally, why do you feel called to that work?

Kidada: I feel called to the work because I think that too many people take the easy way out and run from the violence. You and I right now are not experiencing this violence. We haven't had our lives personally turned upside down and inside out by it. If we really believe in justice, then we have a responsibility to know what happened so we can play a role in stopping it from happening to other people. That's why, for me, I think it's important to understand, to listen to survivors, to not discredit them, to not deny them authority over their own stories about what happened to them, and what was still happening to them.

To that point, I think we have a lot to learn from them. What survivors tell us is that racist violence, it doesn't have a neat beginning, middle, and end. It doesn't end when the person who's committing the violence goes away or stops, it reverberates throughout their lives. What you often see is that survivors often talk in the act of present tense. We use the past tense. We've got the luxury of doing that, but people were still living with the fallout of the violence talk about it in ways that it's ongoing.

Again, I think that because I believe in justice, I want to play a role in helping people know and understand what the violence does to people, how that injustice gnaws away at them, and how it can erode the sense of community so that I can encourage other people to help play a role in righting these wrongs. We can't bring back the dead, but what we can do is to push the lawmakers and our fellow citizens to adopt policies that will stop it from happening to other people. I think that's an important part. Now, I understand how difficult it is to sit with the violence, but I think that if we really believe in justice, then we have to give survivors that time and space.

Kai: You've also said that one reaction to the Charleston Syllabus and your effort to give us the history of that violence in real-time then was that people kept saying, "Why did we know this stuff?" Of course, historians did know this stuff, and I gather that that reaction has shaped how you think about your work now.

Kidada: It has. A lot of people-- The statement that we heard was, "I didn't know about this. Why aren't they teaching this in school?" It's something that's being taught in some college and university classes but not universally. What that made clear to me, and I think to some of my fellow historians, was that just because we were researching or writing, that didn't mean the larger public had access to what we were doing, what we were discovering in the historical records, and the stories we were telling, and not everyone has the privilege of going to college or university and taking our classes. We something, we missed an opportunity to make sure that the larger public understood the histories that we had discovered.

There was this belief that, "Well, I wrote a book. Of course, it's out there. It's available to know this," but that's not how this works. I think for me, and I think for a number of other people, the Charleston Syllabus and the reaction to it, the thirst for more information, made clear that we weren't hitting the audience in a way that we thought we were.

Kai: To that degree, your work is much more public, I gather. You've got a new podcast coming called Seizing Freedom. It's about the Reconstruction Era, which is a period we talk about constantly on this show. It sounds like a bit of a pivot from the pain you've studied this far, I guess, in the sense that it's described as stories of Black people seizing freedom. What is the Reconstruction Era tell us about the relationship between these two things that you study, between seeing the pain and seizing the freedom?

Kidada: One of the things that we know is that African-American seized freedom during the Civil War, changing the course of the war. They made the most of freedom, and they helped expand our democracy and expand its protections to more Americans. What we know is that that work wasn't without a cost because they faced resistance at every step of the way. Freedom wasn't something that could be seized one time and was done. The larger forces of white supremacy were fighting it all along, so our story or the story we tell them the podcast isn't uplifting one but it's a realistic one because we make sure that the audience knows that the resistance is swift, the resistance is strong, and it's violent.

Kai: Swift, strong, and violent.

Kidada: Yes. What we do is we balance that story. It is an uplifting story, but it's also a very realistic one. You will see moments or listeners will encounter moments where they encounter that violence very closely, very clearly because reconstruction is one of the most violent periods in American history, especially for African-Americans, because they pay a price with their lives for trying to be free and safe in this country.

Kai: I don't want to overstate the case, but it just feels so relevant right now in terms of which direction are we going to go in the reconstruction story.

Kidada: It is, absolutely, and that's why I'm really grateful you didn't ask me the question that you asked the previous guest about, "How you're feeling?"

Kai: Oh, we're coming to it, I hate to tell you, but go ahead.

Kidada: On the one hand, I feel lighter, but on the other hand, I know the weight of history. We've been down this path before, and I don't believe that we're in the clear even with a moderate in the White House. I just don't, especially as a Black person and as a historian of racist violence, looking at the state of the world, I'm concerned. I don't believe that I or we can be naive about the danger that white supremacy poses.

Kai: Listeners, coming up, we're going to take your calls about what you have been carrying through the Trump era that you're ready to put down and what you plan to keep close in the way that Professor Williams is talking about now. I am going to ask you, Professor Williams, if you want to answer either of those questions, if there is something you've been carrying through this era that you feel like, "I can put that down now."

Kidada: I think that one of the things I can put down is the constant state of anxiety, the not knowing which way the world is going to be spinning when I wake up every morning. I feel like I have slept a little bit better since the election and especially since the inauguration, just a little bit better, but what I also hope is that the protests from the past summer will guide Americans-- I really hope that Americans have really woken up to the realities of the harms of white supremacy and the violence against Black and brown people, and that they really do mean to make a more just world and society, and that they're willing to put everything on the table to try to make that happen. As a historian, I'm concerned, but there is the part of me, when I put that aside, that is hopeful.

Kai: Well, we'll have to hold both things.

Kidada: Yes.

Kai: Kidada Williams is a professor of African-American history at Wayne State University. She's the author of the book, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. Her new podcast, Seizing Freedom, launches in February. Thanks so much for joining us.

Kidada: Thank you so much for having me.

[music]

Kai: Hey there, a program note, if this particular edition of the show is really speaking to you, I urge you to check out an episode we made in the summer of 2020, right before George Floyd was killed. It's a conversation I had with writer Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah about his short story collection Friday Black. Among other things, we talked about how we both grapple with the aftermath of anti-Black violence. You can find a link to it in the notes for this episode in your podcast app or on our website, wherever you're listening, and you should always check those notes because we have started recommending companion listening from our archives for each episode. I hope you take a look at this one, and happy listening.

[music]

Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright. This is the United States of Anxiety. For the rest of the show, the phones are open. We are entering a new chapter for this show, literally, since we began as a response to the Trump campaign and presidency, and obviously, for the country. A question I'm asking myself and of you is this, what have you been carrying through the Trump era that you are ready to put down, and what do you plan to hold on to? As we take your calls, I'm joined by a friend and co-creator of this show, Arun Venugopal. He's now the senior reporter in WNYC's race and justice unit. Hey, Arun.

Arun Venugopal: Hey, Kai.

Kai: Like I said, Arun was the lead reporter on this show back in 2016, and you'll be hearing from him more this year as he has graciously agreed to host the show whenever I need to step out. Arun, let me put the questions to you. Let's start with the first one, what have you been carrying through the Trump era that you think you're ready to put down?

Arun: Yes. It's a good question. It's really forced me to think about these last few years. I guess what I would say, just professionally speaking, as someone who does cover race but as also just an all-around nice guy and mild-mannered individual, what I aspire to do, I'll put it this way, is to abandon all the tiptoeing, the tentativeness, all the euphemisms that we tend to use, the whataboutism, all that stuff that we do in this business, in the business of American news. Even as we lurch through this entirely new era of mobs and insurrections, I'm not sure if this makes any sense, but I'm just done with-

Kai: It does.

Arun: - the tentativeness that we tend to deploy. There's a certain dogma in news and an inflexibility, this cautiousness, at a time when we, in this business, really cannot afford to be like that. Our craft, it just has to better reflect, and I think really resembled these times in which we live. It has to, I think, better recognize and internalize this scale, this enormous problem that looms before us.

Kai: Well, let's get right to the phones because folks want to talk. Daniel in Bay Ridge, welcome to the show.

Daniel: Thank you, Kai. Thank you, Arun. My name is Daniel from Bay Ridge, and I've been holding on for a lot longer than the Trump years, just anger over the fact that, as a people, we're having to say that human beings should be treated with equality and have equity in the world. I'm trying not to hold every person that I see with a MAGA hat responsible for it. I'm just trying to listen and not hold onto that anger.

The thing that I am holding onto though is an acute sense of responsibility to have my representative, even though it's Nicole Malliotakis, and to have my representatives in the Senate, and to contact every state representative possible to try and hold President Biden's administration responsible for their promises of racial justice and racial equity. You have to remember this is a man who's done an incredible amount of violence to people of color, I'm Latino, to my community, through his crime bill. I would love to see him not only have the opportunity but seize the opportunity to walk that back, and I want to hold onto the idea that it's my responsibility to hold him accountable through my representatives. Thank you so much for taking my call.

Kai: Thank you, Daniel. Let's go to Tony in Queens. Tony, welcome to the show.

Tony: Hi, welcome. Thank you for taking my call. This is actually negative, to be honest. What I carry through the Trump era was this idea of justice, the idea that in the face of injustice, in the face of wrong, the most we can ask for is justice. Even as victims, we ask for justice. That's the best we can get, and that's what we deserve.

After seeing the insurrection, absolutely not. No. I'm at a position now where I can say, honestly, I believe that minorities and African-Americans, especially, deserve more than justice. They deserve some retribution. They deserve to have the other side feel shame, feel embarrassment, to be subject to harm that are outside the scope of our understanding of justice. They should lose properties, they should lose jobs, they should lose social standing.

What I saw during the insurrection really cemented in my mind that it is not fair to ask the victims of injustice to be the civilized ones, to be the ones that forgive, to be the ones that turn the other cheek. It is not fair because the other side will take advantage of it, and they have. They got more out of their injustice than we can get back from our justice, no matter how long it is. The big thing for me is that there used to be a past where I would hold myself down. I would say, "Look, we can only ask for justice. It's the most that we can ask for." I say, no, now. We deserve more than this. We deserve retribution. I wouldn't say violent retribution, absolutely not, but there has to be a sense of shame. There has to be some sense of harm outside of justice, scopes of justice.

Kai: Thank you, Tony. I'm going to let you go so we can keep going. Christian from Richmond Hill. Christian, welcome to the show.

Christian: Hey, Kai, good to be on. I was saying, as soon as Trump came down those stairs-- I'm Mexican. I'm an immigrant. As soon as he came down and called us rapists and murderers, my shield, that I tried so hard to put down, came up. Then, it continued with the children in cages and with the shootings in El Paso. I've been on high alert. I felt like I'm being personally attacked for four years now. Putting my shield down, my sword down, I can breathe a little bit, but also knowing that I have to be hypervigilant. Within my Latinx community, there is antisemitism, there is racism. It's important for me to call that out, to do whatever I can because my liberation is bound to everybody else's. I have hope, but I’ve got to keep vigilant.

Kai: Thank you, Christian. Arun, those are some striking calls. The idea of moving past justice that Tony mentioned, I wonder about that, and how much you hear that as a reporter in communities of color, I guess, and what you think of that, this idea that it's time to let go of justice, we need more than justice?

Arun: I think that's something you might hear in certain private circles, the anger that people feel. I think that the way Tony has expressed here in public is something that's still relatively rare. I think that there is a real asymmetry. We know that when it comes to, say, policing, the way in which the mob was policed versus how Black Lives Matter is policed, I think, is also an incredible asymmetry when we talk about what should the consequences be. That's something that we don't have a language for. People like Tony, I suppose, are trying to craft a whole language of what happens to people who want to bring down your entire society. I mean, it's a very serious act. We've actually haven't thought through that very well because it's all so new.

I think what Christian said, I remember about four years ago walking down the street and when he talked about just putting up your shield, I remember thinking as I was approaching somebody, I was thinking like, "Hmm, does that guy want to punch me in the face? What if he does?" It's a whole new feeling. I had never had that feeling, that too, I live in Queens, and yet, I thought like, "Hmm, my mailman. Does he wish violence upon me? What if he feels like enabled in some way?"

You have so many thoughts you project a lot. I think that that's incredibly tense. Obviously, it's a very tense and traumatizing way to walk through the world, and I think for some people it's nice, as you said and so many of us were saying, to exhale a bit, to maybe think that, hopefully, you can let your guard down although I'm sure that's not the case for a lot of people.

Kai: Well, yes. I mean, that's what Tony is saying. Let's take a couple of more. Let's go to Richard in Brooklyn. Richard, welcome to the show.

Richard: Hey, thanks very much. Throughout the last four years, we have two young children in our family. It's 12 and 6, and now, 7. We are sick of the negative conversation on the dinner table about politics. We're very engaged family, politically. It just was like we're talking about a supervillain all the time, and we're just desperately wanting to be able to talk about issues and not just this bad force in the White House.

We watched the inauguration. Everyone was homeschooling in various parts of the house, and then, we're dipping in. There was a lot of excitement, but my seven-year-old was ecstatic as the helicopter left the White House. It was like a TV show, and it's just so much negativity around the dinner table just vilifying the former president. We're just really excited to get to talking about issues, real issues, and a lot of which are negative, but the baseline, thus far, has just been about negativity of a personality.

Kai: It's so funny to hear you say-- I have plenty of friends with young children who have this, but a seven-year-old that is connected with the idea of this president has left office is really striking about how deeply this got into to our families, in our lives. I have a follow-up question for you. If you're going to let go of that, you're happy to get negative politics out of your dinner table life, what are you going to pick up?

Richard: First of all, it's really hard to let go of that negativity. It's amusing and interesting, like the latest Netflix show, to talk about the burden. Anyway, we're just trying to steer the conversation around to rejoining the Paris Accord and just issues that can be achieved right now, and talking about what people's agendas are now, that are in power, and how much good that can potentially bring. Again, there's a lot of dark things happening and things that need to be fixed that are weighty, but at least, we can start from a place of hope as opposed to just constantly talking about Trump.

Arun: It's funny. Thank you, Richard, for that because I think it's so true. It's not just people in this country. I have friends who live in other parts of the world who say, "This is all we talk about," 2017, 2018, it's just on and on. I would almost set boundaries in the morning if my wife was like, "Did you hear what--" I'd be like, "No," just put my hand up. I'm like, "Not before my tea. Not until 7:45." I'm negotiating here, and not after 10:45 at night. I'm like, "We need to carve out zones of exemptions from that thing that I think had all of us permanently seized. I think it's nice to think like, "What does that mean? What do you hand over that time to now?"

Kai: Let's go to Denisa in Washington Heights. Denisa, welcome to the show.

Denisa: Hi, Kai, how are you?

Kai: Very good.

Denisa: Putting down is that dread I felt when I first saw Trump got himself as a nominee, and I just was like, "This is not good." It was the dread that encompass a lot of his presidency and not knowing and the uncertainty of what's going on in Washington because it just seemed like this circus. I'm politically active so it was really hard for someone who enjoys politics, the goodness, the figuration of democracy. I always knew this path was on its way but to really see it play out with the presidency was really striking.

What I carry with me throughout the whole time was his hope because I work as a public servant, so I know there are people in Washington that, despite working under his administration, were trying, still doing good work even under cut budgets or anything like that, but that hope was still there. Once the Inauguration Day came and I saw, specifically, Madam Vice President Kamala Harris walk up the steps, I felt really emotional for the first time after a long time, and I'm like, "Okay, we're finally in the next chapter of this American history and see where we can take it from here."

Kai: Thank you for that, Denisa. We also have a tweet that I think pretty well encapsulates how a lot of people are probably feeling. It's how I'm thinking about it. It says, "I'm looking forward to putting down the urgent anxiety that the world will go down in flames if I do not act right now while holding on to the practice of being an active participant in pushing for a better tomorrow." There you go.

Arun: Yes.

Kai: Let's go to Nicky in Harlem. Nicky, welcome to the show.

Nicky: Hey, Kai, thanks for taking my call. [chuckles] We definitely encapsulates what a lot of people are thinking. What I can let go off is that long, long, long breath I was holding on to throughout the entire Trump presidency because I thought this man was unstable and he actually won in a TV channel instead of the presidency. What I'm holding onto is accountability. One thing I've noticed from older generations is that they talk about us millennials and Gen Z-ers saying that we're so sensitive about the things that people say or post on social media. We're not being sensitive. We're actually holding people accountable for the things that they're saying.

This man-- I'm going to call him 45 as the codename because I don't like saying his name. 45, he used a series of lies to create an entire movement to stir up the feelings that have been in American white men for over 244 years and created a movement out of that hatred, out of that imperialistic grotesque nature that is the American white men, white Christian men. I'm holding on to the history, and I'm making sure that generations under me are reminded of this moment in time because it's not okay to just forget it.

Kai: Thank you so much for that. Arun, we got a couple of minutes left. First off, briefly, the point Nicky made about the changing conversation and accountability in the conversation, that is something that it feels like is dramatically different in the course of the last four years in terms of-- What do you think about that?

Arun: Absolutely. He said that he's Gen Z. My daughter is too. I think that there is a level of anger or just simply the unacceptability of it all that I see and I hear from people who are younger in a way that I think is striking and just refreshing. It's nice to have people who are entering into the political discourse, and who are not willing to tolerate certain norms that, say, some of us may not necessarily be happy about but somehow reconcile ourselves to. I thought Nicky expressed really well.

Kai: Maybe it's that. You haven't answered yet what you're going to carry, that you picked up, that you're going to carry into the Biden era as another person with power now starts to shape our lives.

Arun: I was listening to you talk earlier to Jericho Brown, and it was just so beautiful, what he had to say. It reminded me of just how much has become banal, cheapened, desensitizing in the last few years. People, they say certain kinds of stock phrases, "Why are you surprised? I'm surprised, but I'm not shocked." I don't want to become so glib. For me, I have lost a lot of faith in humanity, but one thing that keeps me rooting and retains a certain type of sense of mystery is art. It's our ability to turn a phrase or create a melody or just a story that swirls within us and transforms us.

Kai: Arun Venugopal is the senior reporter in WNYC's race and justice unit. He was the lead reporter for the launch of our very show back in 2016. Good talking to you, Arun.

Arun: Thanks, Kai.

Kai: Thanks to everybody who called in, apologies to those who couldn't get to. You can always email me at anxiety@wnyc.org. A special thanks to Howard who emailed me a poem this weekend after he heard the promo. I'll look forward to tweeting it out. I'm Kai Wright, thanks for spending this time with us.

[music]

United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Jared Paul makes the podcast version. Kevin Bristow and Matthew Marando were at the boards for the live show. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Marianne McCune, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Karen Frillmann is our executive producer. I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter at Kai_Wright and you can always join us for the live version of the show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern. Stream it at wnyc.org or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening and take care of yourselves.

[music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.