The Misunderstood Era of Crack Cocaine

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

Regina de Heer: When you hear the term crack cocaine, what do you think of?

Female Speaker 2: I think of urban areas with impoverished people.

Female Speaker 3: People like laid out on the corners and asking for change.

Female Speaker 4: Junkie do anything for it. Selling their mom and stuff and doing some crazy stuff to get it.

Male Speaker 1: Whitney Houston's interview with Crack is Whack.

Regina de Heer: Say more.

Male Speaker 2: Anybody that participates in those activities, I'd probably stay away from.

Female Speaker 3: People trying to get themselves together. Trying to lie and be like they want money just to go get other stuff. I think of people that's really addicted and trying to get themselves off of it but it don't work.

Male Speaker 3: Something not good for your body.

Female Speaker 5: When I think of crack cocaine, I think about how it took over DC in the '70s and destroyed the city and now it's coming back.

[music]

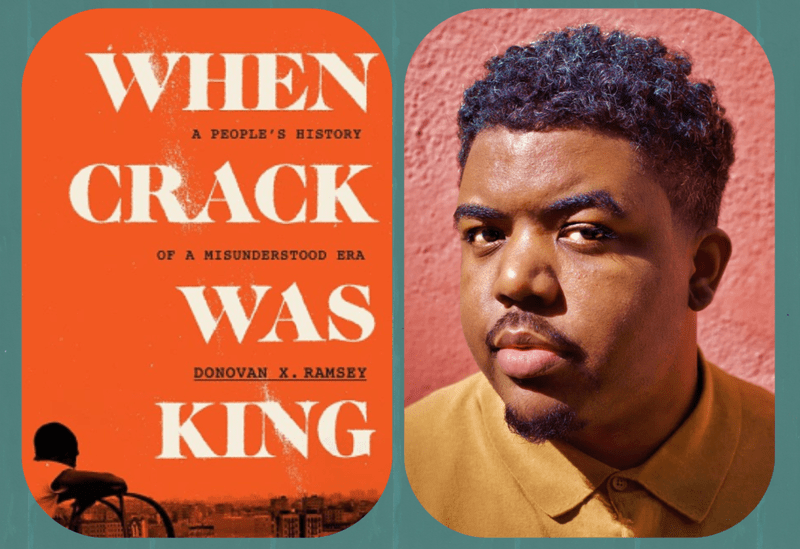

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. It's hard to overstate the impact that crack cocaine had on American life on our culture, on our politics, on our economy, and on our story about ourselves as a nation. For more than a decade, it was just everywhere and so were the many myths and misunderstandings that surrounded and frankly prolonged the epidemic of addiction. Journalist Donovan X. Ramsey says the epidemic invades his earliest memories. It was just that present. He needed to understand it. He needed to get a more clear-eyed view of this thing that became almost like a boogeyman and the result is his new book, When Crack Was King: A People's History of a Misunderstood Era. Donovan, thanks for coming on the show.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Hey, Kai, thank you for having me.

Kai Wright: This book is full of cautionary tales and missed signals or at least that's how I read it. I want to start with one story that you tell that's not explicitly about crack but that I think says a lot about your project here. It's the story of Washington Post reporter Janet Cooke in 1980. She was a rising star at the Washington Post, a Black woman who published a now infamous story. The story was called Jimmy's World and it was full of shocking details that frankly really called out for skepticism. When it hit the streets in 1980, it was rapturously received by readers and political leaders alike. What was it that folks would've read when they picked up the Washington Post that day in 1980?

Donovan X. Ramsey: People would've picked up the Washington Post and saw on the cover a story about a nine-year-old heroin addict who was the product of an incestuous relationship between his grandfather and mother, whose stepfather calmed him down every day after school by shooting him up with heroin who lived in a heroin shooting gallery. This was on the front page of the paper. Of course, because Jimmy was an anonymous source, according to Cooke and the Washington Post, it was accompanied by illustrations.

As you mentioned, there were lots of signs obvious to anybody that's ever made the news that the story was a complete fabrication. One, he had never encountered any public health workers, social workers in his nine years of life. There was no record of a Jimmy at schools through the hospitals, any of that. People who had covered the community that Jimmy supposedly lived in DC. Other reporters, mostly Black reporters, said, I've never heard of this story, that nobody knows Jimmy. There were lots of reasons to not publish the story. The Washington Post not only published it but put it on the front page of the paper and nominated the story for a Pulitzer Prize.

Kai Wright: Which it won.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Then it was discovered that it was a complete fabrication that she had made up the story whole cloth. Janet Cooke who was at that point, the first Black woman to win a Pulitzer for reporting, became the only person to ever give a Pulitzer Prize back.

Kai Wright: What was it about the psyche at the dawn of the '80s, you think that made people work so hard to believe this story? You had to go out of your way to believe it really when you look back at it.

Donovan X. Ramsey: I think that from the earliest moments of this nation's history, there has been a need to make Black people pathological otherworldly beneath humanity. For a long time, people said it was biology and when that was no longer popular, it became culture. What we see in Jimmy's world is a story perfectly made to explain away the ills of the urban ghetto through a sick Black culture. Everything sick about Black people that you could imagine was going on in Jimmy's world. That desire to tell that kind of story then continues and explodes during the crack era.

Kai Wright: You also write about the psyche among different classes of Black Americans at the time and you have a whole chapter on the song Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now. This is the 1979 smash hit from R&B Duo, McFadden and Whitehead. What does the song represent in Black America at the time?

Donovan X. Ramsey: The song comes out of Philly International during the '70s and it's a beautiful song with a great funky disco, [unintelligible 00:06:23], lots of horns.

[MUSIC - McFadden & Whitehead: Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now]

Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now!

We're on the move!

Donovan X. Ramsey: It emerges in the '70s as a new Black national anthem. This idea that whatever was holding us back is now behind us and there's this bright future ahead of us. It's pre-Reagan's morning in America. It's the same sort of vibe. I think that it's so representative of a period that I didn't know of before. I'm born in 1987, so the crack epidemic is actually older than me. I wrote this book in part because I wanted to understand who we were as a community before crack. I saw in that period symbolized by this song, incredible hope that we could enter the mainstream and maybe hold on to some of our Blackness in the process.

So you see music like that but then you also see shows like The Jeffersons that are about moving on up. You see Webster who's adopted by a white family and that story's about a fish out of water, a blackfish out of water. The same thing with different strokes and Gimme a Break. Again, there are these Black characters who come from Black neighborhoods who are now in white spaces and it's there in the music as well. It's legacy artists like Aretha Franklin crossing over with George Michael or Patti LaBelle putting away the Go-Go boots and the [unintelligible 00:08:12] of LaBelle to make songs like On My Own with Michael McDonald. There was a lot of hope that Black people could cross over and I should say in the process also exposing a rift along class lines in the Black community.

Kai Wright: You write about that with this song Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now how it's almost a taunt to the part of the Black community that is not crossing over. You're keen for readers to understand a grief, I think is the word you use. What is the grief you're talking about?

Donovan X. Ramsey: I came up with that language because I wanted to understand what would lead people, really a generation of young people to addiction. We use words like disaffection now when we talk about white folks in the middle of the country using opioids to explain how a feeling could sweep up a large group of people. I don't think that we ever thought we as a nation about all that Black Americans were mourning in the '70s and '80s.

The civil rights movement was an incredibly hopeful period marked by incredible leaders who did things that were truly otherworldly. That Martin Luther King Jr.'s commitment to nonviolence and his hope in America was really beyond anything that I think the average Black American could imagine. Then as a nation, we saw him die a Black Death. We saw him killed a thug on the street. That's a blow. That not happened to just him but so many of our leaders. Then people to still have to live in America's ghettos and for the rest of the country to move on like it never happened.

I think that grief really is the only word for that. When you think critically about what a substance like cocaine is, it's a stimulant. It gives people feelings of euphoria and confidence, and fearlessness, and energy. I think that even just looking at crack as a substance can suggest what it was people were going through, who wanted to use it, that they were down and wanting to feel up.

Kai Wright: Your language when you write about it is quite striking. You call it tailor-made. Crack is tailor-made for the moment.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Yes, that was something that aside from just studying the substance in my interviews across the year, I traveled to all the hardest hit cities about 10 in total, and I interviewed people who were impacted including hundreds of people who actually use crack. That was something that really came through was that these people wanted to feel good. Whether they were coming from a lot of grief, both personally and on a societal level, or whether or not they were celebrating that they were often the person having the most fun at the party, and they just stayed at the party too long, and that they didn't know what the nation's response would be to the way that they party.

That's important to highlight because I think lots of those folks got flattened out to this crackhead trope, and as a nation, we didn't ask enough questions about who they were and the choices that they made.

[music]

Kai Wright: I'm talking with journalist Donovan X. Ramsey about his new book, When Crack Was King: A People's History of a Misunderstood Era. We need to take a break. We're not taking calls this week, but I do want to ask you a question about an upcoming show. If you eat a plant-based diet, what pushed you to make that change? Did it have anything to do with climate change? You can answer by going to notesfromamerica.org and looking for the record button to leave us a voicemail right there. Please do include your name and where you're calling from, and we will use it in an upcoming show.

Coming up, more of my conversation with Donovan Ramsey. We will get into that crackhead trope he mentioned. Stay with us.

[music]

Regina: Hi, my name is Regina and I'm a producer with the show. You may remember that last year, we started the Notes from America summer playlist. We collected submissions from you and curate a playlist that everyone could enjoy. Well, summer is here again, and I'm happy to announce we're launching our second summer playlist. A couple of weeks ago, I had a conversation with the guys from a band called Wake Island. They talked about how music has become such a powerful outlet for identity, filling a need as a search for their place in the Arab American diaspora. Now it's your turn, what's a song that represents your personal diaspora story?

Here's how to send us your response. Go to notesfromamerica.org and look for the record button to leave us a message. Start with your name and where you're recording from. Then tell us the name of that song, the artist, and a short story that goes along with it. Feel free to include a little bit about your background as well. Make it your own and please make sure that your recording is at least a minute long. We'll gather all the songs and your stories in Spotify playlists that will drop regularly all summer long. All right, I think that's everything. Thanks for coming to my TED Talk and I can't wait to hear from you.

Mele Speaker 4: Is there anyone out there who's still isn't clear about what doing drugs does? Last time, this is your brain. This is drugs. This is your brain on drugs. Any questions?

Boy: Drugs, some of the big kids do them, but my mom and dad helped get this D.A.R.E. anti-drug program in our school.

Girl: It's run by specially trained police.

Boy&Girl: Now, we're saying no to drugs.

[music]

Kai Wright: Welcome back, it's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and I'm talking with journalist Donovan X. Ramsey about his new book, When Crack Was King: A People's History of a Misunderstood Era. Donovan, I grew up in the 80s. The story of crack was everywhere in my youth. It was just an overwhelming part of the public conversation trickling all the way down to the playground. We would call each other crackheads. You write about how it came up for you as the boogeyman in your life too. Talk about that.

Donovan X. Ramsey: It did. Born in '87, crack always existed in my life. HIV/AIDS always existed. I was steeped in this great fear of things that previous generations hadn't been. I went through the D.A.R.E. program.

Kai Wright: You yourself, you were in the D.A.R.E. program?

Donovan X. Ramsey: [chuckles] Yes, I myself. I got a D.A.R.E. T-shirt, and at the end of the year, we went to a concert that we were escorted by our school D.A.R.E. officer because each school was assigned to officer who would ask you questions about the drug use in your community and in your family. It was a snitch program really.

[laughter]

Kai Wright: Indeed.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Then you would learn songs about being off of resisting drugs. The reward at the end of the year was a T-shirt and they took you to a concert where a bunch of police officers who are also musicians perform the songs that you learned.

Kai Wright: Wow.

[laughter]

Donovan X. Ramsey: That was who taught me about drugs really. That, and then of course what I actually saw in my neighborhood. I grew up in Columbus, Ohio, and we were very, very poor growing up and raised by a single mom who did her absolute best and tried to protect us from the environment that we were in. I remember my neighbors, people of my community being strung out on crack.

My very first bike that my mom saved for years and years to get-- probably, I didn't get it until I was maybe seven or eight. The front wheel blew out on my bike. I remember I might have been a mile away from home and I was afraid to go home and tell my mom that I had messed up my bike. I'm standing there trying to figure it out, and this guy that I seen around comes up and he says, "It looks like you've lost some air in your tire. I can fix that for you." I'm so excited. I gave him my bike. He disappears behind the house 10 minutes past, 20 minutes past, an hour passes.

I realized, "I think this guy stole my bike." I have to go home and tell my mom. The first thing she says is, "Why would you give up your bike to a crackhead?" When I described the guy, she knew who I was talking about. There's no way that you can grow up like that and not be a little bit afraid of your neighbors and afraid for what could happen to you. If you made a poor choice as they had, they definitely steered me away from drugs. I do think that there was a consequence, which is that I felt a lot of distance between me and those people.

Kai Wright: I don't think nearly enough has been said about this particular dynamic and the way this epidemic tore inside the community, the relationships between Black people in the same neighborhood, in the same families, just the wound it left.

Donovan X. Ramsey: I think that that dynamic is marked by so much fear and shame, and distrust from really the people that you need to stay alive, that we became actually more vulnerable because we didn't have each other anymore. That is the truth for people who distance themselves away from family members that were selling drugs or doing drugs, or just also the way that young Black men became suspects even within our community.

The ways that misbehaving Black children were suspected of being so-called crack babies. You can't lose too much weight in the Black community too fast without somebody checking in and be like, "Hey, are you on that shit?" So to speak.

Kai Wright: To this day?

Donovan X. Ramsey: Yes. It's that there was distance that was put there and a lot of people put physical distance between themselves and the community that Black neighborhoods became places that even Black folks didn't want to be anymore. You saw a big move in the '80s into the '90s of upper-middle-class Black folks or just folks that could to the suburbs. For that reason a subject that you've studied a lot, gentrification, I believe is a consequence of the crack epidemic. That almost to the one, that those neighborhoods that are now full of multimillion-dollar homes were owned by somebody's grandmother who decided that she just couldn't stay anymore. That they were too many bad memories.

Kai Wright: That's a really good point.

Donovan X. Ramsey: So I like to joke and think about this is how I keep my spirits high when I'm doing work like this is I imagine the movie about the ghost of the Black folks lost during the crack epidemic, haunting their gentrifier counterpoint or counterparts, sorry, I'm a little sick, but--

[laughter]

Kai Wright: I'd watch the movie. When Hollywood ever comes off strike, they can call you. [laughs]

[music]

I was fascinated to also learn in your book just the history of cocaine, which I knew in broad outline, but not in this detail. It began as a stimulant that Spanish and slaves gave to the Incas to get greater productivity from their forced labor. How did it evolve into a recreational drug in the late 19th century in Europe and the US?

Donovan X. Ramsey: It was really powerful to learn that long history of the substance because it went from just leaves that people in the Andes chewed for a little extra energy to-- once the Spanish colonizers saw that it energized them as you explained that they gave it to them to keep them productive. But once European scientists started exploring coca leaves and then refined it into cocaine, it became incredibly popular all over the world.

Sigmund Freud was one of Cocaine's earliest enthusiasts. He wrote a paper called Uber Coca about what he said was a magical drug. He later had to go into recovery for a cocaine addiction indeed but you know that it became popular all over the world. It was in drinks, as many people have heard, like Coca-Cola, because people thought it was a magical tonic that gave you a little extra energy. Like adding caffeine to something like an energy drink.

Sorry, big caffeine people but I use it as an analogy because that then opens up this understanding of substances and substance use versus substance abuse and the addictive quality of lots of different substances whether it's sugar or cocaine or caffeine or tobacco. That these things have impacts on us, and sometimes we think of them differently because of how they're classified, literally just how they're classified by the government, but lots of things have potential for addiction and harm.

Kai Wright: At some point, cocaine became associated with Black laborers in the early 20th century. How and why did that happen?

Donovan X. Ramsey: As had been with the Incas where the drugs became available to them for productivity, they became available to Black workers on railroads and shipyards. Anything associated with people of color, it then became demonized. There was this idea that cocaine made Black men especially violent. It made Black men do the thing that America is always been afraid of, which is sleep with white women. There were lots of stories of white women being raped by Black men hopped up on cocaine. Scientists wrote in the New York Times a paper about negro cocaine fiend was the part of the headline that cocaine made Black men both better shots with firearms and also impervious to bullets, if you could imagine.

Kai Wright: I can imagine that.

Donovan X. Ramsey: To think of that idea of being baked in that early. Even the language, I remember when I was growing up that people that were drug addicts were referred to as fiends, that people would say, "Oh, that's a crack fiend." Tupac says on, Dear Mama, "Even though you were a crack fiend, you always were a Black queen."

[MUSIC - Tupac: Dear Mama]

And even as a crack fiend, Mama

You always was a black queen, Mama

I finally understand

For a woman, it ain't easy tryin' to raise a man

Donovan X. Ramsey: That language comes in the early 1900s. We even have an event like the Atlanta race riots kicking off because of stories ran in the Atlanta Journal and the Constitution that Black men had raped white women while they were high on cocaine. Then you have then hundreds of white Atlantans going to five points in downtown into Auburn Avenue, where lots of the Black bars that presumably sold cocaine lace drinks were, and destroying those businesses, and then going into the residential neighborhoods and massacring Black communities. That history and the association of drugs and danger when in the wrong bodies is over 100 years old.

Kai Wright: It's also striking how you can hear echoes of that history in the political rhetoric and the ideas that emerged at the height of the cracked epidemic. The idea of the "Super predator youth" who have these never before seen levels of depravity,

Donovan X. Ramsey: It was always there because the substance, it could be anything. That it could be any substance, but it just mapped so well onto ideas of Black pathology. Whether it's cocaine or whether it's cocaine in its smokeable form and crack or marijuana, you could put any substance in that place and it will be then a great explanation for why Black men are X, Y, Z.

Towards the echoes that continued. We get also this idea of crack addicts being zombies, that that's the language that you see in a lot of reporting from the era that crack somehow made these heartless thoughtless zombies of Black people. Again, it is this language that dehumanizes the subject. Once a person has been dehumanized, then you can do anything to them.

Kai Wright: It's worth pointing out that that era in the early 1900s that we were talking about from that comes the first-ever federal anti-drug law in 1914. What did that law do?

Donovan X. Ramsey: What that law did was it made it illegal to possess cocaine. That becomes a theme that as a nation, we've always been more focused on drug possession at the user and street dealer level than we have been at the trafficker and supplier level. That we very early on made the decision to criminalize people who are in possession of the substance and not to try to what they call interdiction, which is a policy of preventing it from actually entering the country. The consequences for that is that you don't help often the most vulnerable people, that you actually criminalize them and thereby creating a cycle of trauma that continues their drug use. Then later on that feeds the mass incarceration system.

[music]

Kai Wright: Your book is built around four characters that you follow throughout their lives. First off, it's striking to me that you're halfway through the book before any of those people actually encounter crack. Is that intentional to make crack the secondary character in this story?

Donovan X. Ramsey: It was. It was very intentional. The work of this book is in part to document the crack epidemic and make sure that people have a clear understanding of its rise and fall, but to also make clear its impact on the lives of human beings. For me, it was necessary to have those four characters and to weave their stories throughout. Also to explain who they were and what their communities were like before they actually encountered crack so that way people can feel the loss when crack does come and can also see just how deep of a hole they climb out with little to no help.

Kai Wright: They're each kind of a story of a place as well. Lennie, one of the characters who is now a drug counselor really has a harrowing and difficult life story to read that includes addiction. Her story is really the story of South Central Los Angeles. First off, why is South Central such a key location in the history of crack?

Donovan X. Ramsey: I would say that both Lennie had to be in the book and South Central, had to be in the book. I really couldn't tell this story without talking to the people who experienced the worst of the epidemic. That was Black women who found themselves addicted to crack, that they saw what happened from the absolute bottom up.

I was really blessed, I would say, to be able to meet Lennie to have her share her story with me, and then also for her to tell me the story of South Central as this place that was a destination for the great migration. Black folks from Louisiana and Texas who got great jobs building airplanes and who bought beautiful homes in South Central LA and who, when those jobs went away, their neighborhoods went from working-class neighborhoods to areas of concentrated poverty. That they are then also these sites for like, just great need that people need jobs that they need something to do, they need places to go, and crack fills that hole. Then LA becomes ground zero for the crack epidemic.

[music]

Kai Wright: Coming up, how Los Angeles became ground zero and what could have been different. It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright more with author Donovan Ramsey about his new book When Crack was King after a break.

[music]

Kai Wright: Welcome back, it's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and I'm talking with Donovan Ramsey about his new book When Crack was King: A People's History of a Misunderstood Era. The book revolves around four characters, each of whom were swept up in the crack epidemic in some way. Lennie is a woman whose story is also the story of South Central Los Angeles where the epidemic really began. Donovan introduced Lennie to us a little bit. Her story is, unfortunately, one of the kind of abuse that is far too common among Black girls.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Lennie Woodley, Miss Woodley, as people call her today, is a remarkable drug counselor in Los Angeles who is beloved by her clients who she has helped through all types of addiction. Her story starts in South central LA as a little girl who she experiences a lot of isolation because she is physically abused by her mother and sexually abused by her uncle who she and her mother live with. She goes through years of that before she finds a way out. That was both sex work and drugs. Sex work allowed her to have money and a level of freedom and autonomy and drugs allowed her to do the sex work.

That is an important point to make because these things don't just happen in isolation, that people try drugs and experiment with drugs for reasons, but they abuse drugs and stay addicted usually for much larger reasons. A person's life has to facilitate drug abuse and addiction. Her life created a situation where she was addicted to crack for decades, for nearly 30 years. Lennie is so funny, so beautiful, so smart. [laugh] Someone does not survive on the streets for that long without being clever. She's exactly that.

Kai Wright: One of the interesting things about her savvy that you describe is-- she becomes a sex worker at age 13, and she's traveling back and forth between her life in South Central to Culver City, and she recognizes that her invisibility in Culver City is a tool.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Yes. Lennie realized that in her neighborhood, people knew her and some people saw her, but that as somebody in a Black female body, that she could move through Culver City where many of the studios are in Los Angeles, and be ignored by most people except the Johns that wanted her. She decided that that is where she would do her work. That all that she had to do was get dressed and sit at a bus stop in Culver City and men would come. That the police wouldn't bother her, people wouldn't ask her why she was there, but the men that wanted her would see her. That was what she did.

I think that, of course, Lennie made choices that were directed really by the trauma that she grew up in. I think that our society, again creates a space for that, that a lot of people failed Lennie, aside from just her mom and her uncle, that those of us that maintained spaces, physical spaces like where she worked as a sex worker in Culver City, but also just ideas like Black girls are to be overlooked and ignored, that that creates an opportunity for so much harm for the people who see them for the wrong reasons.

[MUSIC - Grandmaster Flash: White Lines]

Kai Wright: LA is the launching pad for freebase cocaine. Let's start with a 101. What makes Freebase freebase?

Donovan X. Ramsey: Sure. Freebase is the original name for crack. If you listen to songs like White Lines by Grandmaster Flash, he says, "Freebase, don't do it."

[MUSIC - Grandmaster Flash: White Lines]

And if you get hooked, baby

It's nobody else's fault, so don't do it.

Freeze

Rock

Donovan X. Ramsey: That's a really early documentation of this phenomenon. The term comes from a chemistry term, which is to separate the base of a compound from its other elements, thereby making it smokeable. Something like powder cocaine you can't set fire to it and smoke the vapor, it'll just burn the drug and destroy it. Has to go through a chemical process where you get crack, essentially. In my research, I tracked down a book called The Pleasures of Cocaine which is available on eBay. You can find old copies of it. Just for the record.

The Pleasures of Cocaine was published by a independent publisher in the Bay Area and sold out of head shops. The guy that published it, he was just a drug enthusiast and a hippie who had this bookshop near Berkeley who had learned from college students in the area how to do this chemical process where you could take powder cocaine and you could expose it to ether or other volatile chemicals and mix it up and then it would separate its different parts and what rose to the top of this fluid you could scrape off, it was this little crystal that you could crack into little pieces. Later the name crack comes from that action and smoke it.

I want to highlight that crack comes from the Bay Area and this community of people with chemistry knowledge that it is not the invention of young men in South Central Los Angeles. It's drug enthusiasts in the late '70s early '80s who create freebase. Freebase in its earliest forms did not really take off because the process was so volatile, people would blow themselves up trying to make it. Someone later on figures out a way to do it with regular old baking soda. You mix baking soda-- I probably shouldn't tell people how to do it, but it's a very simple process. As a result, you can create large quantities of crack from relatively small quantities of powder cocaine, which then makes the drug cheaper and more accessible.

Now, in terms of why people think it's different from powder cocaine, that has to do with the fact that anything that you smoke gets immediately into the bloodstream. It's a more intense high than something that, let's say, you would snort, but it's also shorter-lived. That means that people then binge the drug to stay high. People just saw that different mode of consumption and pattern of use and they said, "It must be more addictive." In reality, it was always just cocaine. That cocaine is cocaine.

Kai Wright: Who is Rick Ross? Not Rick Ross the hip-hop artist, but Rick Ross who played an important role in the history of crack cocaine. Introduce us to him.

Donovan X. Ramsey: Freeway Ricky Ross was a young man that grew up in South Central in the '70s. He was actually a budding tennis player. Ross was on his way to college to play tennis, but it was discovered that he couldn't really read, that he had been passed grade to grade without ever really being literate. That completely dashed his dreams of a college tennis career. He then went to trade school, and in trade school, he met a guy who was a Nicaraguan national who asked him, "Hey, you ever thought about selling drugs?"

[laughter]

It just so happened that he had a friend who had introduced him to selling powder cocaine, but he was able through this connect that he met in trade school to get his hands on literal tons of cocaine. He learns the recipe for freebase cocaine made with baking soda, so the safe, non-volatile way of doing it. Unlike other drug dealers of his time, he is a businessman who decides that he could create a large network through friends of his that were Bloods and Crips, and he could build an empire.

That's exactly what he does. He becomes sort of the godfather of crack because he's the guy that names it ready rock. He's the one that spreads the recipe through this network of gang bangers and drug dealers. He does for crack what McDonald's does for the hamburger, which is its marketing, its placement. He created an empire as a result.

Kai Wright: Part of what happens for Rick Ross, as I understand it, and allows this turning cocaine into McDonald's, is the affordability of cocaine at the moment. Why did cocaine suddenly become so affordable?

Donovan X. Ramsey: We had a glut of cocaine in the United States in the late '70s and early '80s. This is because the federal government's drug policy under Richard Nixon, when he declares the war on drugs, he sets up these offices that are focused primarily on heroin and marijuana coming through Mexico. For the rest of the '70s and early '80s, cocaine is just coming into the US from Central America and all of that activity goes really uninterrupted by the US government. Then cocaine's everywhere. It becomes super popular and really glamorous in the '70s.

You can look back to magazines like Esquire and GQ, and they're selling little cocaine spoons that hang from your neck. That's how just regular it was in the American imagination. By the time Rick Ross is ready to become Rick Ross, there's so much cocaine available. He meets this guy who becomes his plug, who becomes his connect that can get him really endless amounts of cocaine.

The reasons for that are vast, but I will speak specifically to a geopolitical situation in the 1980s, where the people of Nicaragua had elected a president that the US government was not fond of, and we wanted to disrupt what was happening in that country. There was an effort from the Reagan administration to give them funding and to give them weapons, and that had been denied by Congress.

A lot of folks might remember the incident with Ollie North, the Iran-Contra affair, where a plane crashed in Nicaragua that was full of weapons from the United States. It was exposed that we had this covert operation where if we couldn't send them money, we would just send them guns. What was later exposed was that the Contras were not only receiving guns from the US government but that the US government was in many cases turning a blind eye while they traffic cocaine into the United States.

Kai Wright: We are not taking calls this week, but I suspect if we were, this would be the subject of most calls. I guess what I want to ask you is to put it in context, someone who has now done this exhaustive study of this epidemic, where does the fact of the US government's complicity in the shipment of cocaine into the United States, where does that fit in the story of the epidemic?

Donovan X. Ramsey: I do believe that a policy of interdiction would've kept the crack epidemic from happening. That is not the same as saying the US government engineered crack and dropped it in our communities. I think that the US government neglected to interrupt something that was obviously harming communities of color because it didn't care. Individual politicians then made careers of continuing, doubling, advancing that harm. Writing this book really exposed for me just how deep the harm goes in America when it comes to anti-Blackness. I came out of this process understanding that Blackness is not just a racial identity, that Blackness is a position in this country. That to be Black is to be positioned the closest to harm.

[music]

Kai Wright: Having gone through this study, where's a point where you look at it and say, "We could have done something different right here. This would've been different if we had made a different choice right here"?

Donovan X. Ramsey: I think that if we had beefed up our healthcare system so that way those first-line healthcare workers could identify what someone going through addiction looked like and put them into a treatment program, that we would've saved a lot of lives and we would've ended the epidemic early. That's to say nothing of an actual effort to disrupt the flow of drugs into this country.

The same can be said for the drug epidemic that we're dealing with now, which is opioids. That we are living through an opioid crisis because there was a glut of prescription meds in this country and that that was not disrupted. That we allowed those drug traffickers in the form of big pharma to push their product to as many people as possible and they got people hooked. Then finally, when it was time for us to step in, people could no longer get access to prescription pills, so they went to street drugs like heroin. Then once folks got hooked on heroin and that becomes harder to get, you get a synthetic opioid in the form of fentanyl that is also has a really high likelihood of overdose. We're still now dealing with that third wave of the opioid crisis.

Kai Wright: Did you find what you were looking for writing this book?

Donovan X. Ramsey: I did, Kai. I have to say that when I started writing When Crack Was King it was because there was not a book that explained crack's rise and fall to me, but also explained to me how my community experienced it and how it was that we survived it. There are lots of things that I would change about the book.

[laughter]

As I'm sure you know any writer would want to go back and do another draft, but I feel ultimately I have those answers and there's enough there to start a conversation. That I hope that anybody that reads this book and sees a familiar scene or remembers somebody that they lost touch with, that it's easier for them to have that conversation because this book exists.

[music]

Kai Wright: Donovan Ramsey is author of the new book, When Crack Was King: A People's History of a Misunderstood Era. Notes From America is a production of WNYC studios. Find us wherever you get your podcasts. On Instagram @noteswithkai. We are trying out a lot of new stuff there on Instagram, so come check us out and talk to us. We will always respond. Theme music by Jared Paul, mixing this week by Mike Kutchman, reporting, producing, and editing by Billie Estrine, Karen Frillmann, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. Andre' Robert Lee is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright and I will talk to you next week.

[00:51:51] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.