Michael Calvert’s Good, Too Short Life

Kai Wright: We are living through extreme times, a new dire threat seemingly every month. The heat waves and the active shooters, one new COVID strain after another, each more infectious than the last. Now we got monkeypox. As our editor, Karen Frillmann put it in a meeting recently, it feels like we're all being constantly chased. Truthfully, some communities have faced this strain before.

Some of us have faced down the worst case scenario, and even a mid horror, found ways to maintain the little joys that a lot of times we fought hard to get in the first place. Karen has actually seen this up close herself. She was here in New York in the early days of the HIV epidemic in the '80s at a time when a diagnosis with this mysterious illness was essentially a death sentence, one often handed down to young people in the prime of their lives.

Karen Frillmann: I volunteered for a small agency to go in and to clean and to bring food. I remember going and meeting this young man, his name was John. When I first started to care for him, I felt I was taking care of someone my brother's age. Then within a few weeks, this young man aged before my eyes and he was gone in three and a half months. It is so frightening to see life just slip away.

Kai Wright: The experience made Karen want to document those lives. Not the deaths, but the lives. We shared a recording she made during that time in a previous episode. I just felt this week I needed to revisit that. She told us the story of a guy named Michael Calvert.

Michael Calvert: I'm wired.

Karen Frillmann: I met Michael Calvert through a friend of a friend.

Michael Calvert: Did you all get specific questions that you want to ask me, anything?

Karen Frillmann: It was July of 1986 and he invited me up to his apartment-

Judy Weninging: Maybe we should mic him with a regular mic.

Karen Frillmann: -and Judy Weninging, who was my producing partner at the time?

Judy Weninging: How have you been feeling?

Michael Calvert: I've been feeling rotten. That's the truth.

Karen Frillmann: He was 27 years old when I met him. He was living in Chelsea.

Michael Calvert: I don't really know why, but just rotten. I think maybe it's been as mentally a problem as it has physically, the physical pain and the [crosstalk].

Karen Frillmann: At that time I think the thing that was really grounding him, he was a member of the People with AIDS Coalition, which was an advocacy group and a support group for these people who were getting sick. There was so much of a stigma around it. People didn't understand it. Michael Calvert had started giving talks, educating healthcare workers about what this disease was doing.

Michael Calvert: I showed people my lesions today, a spot that I don't even look at on a regular basis. I don't want to see them. I put on a long-sleeved shirt so that I don't see them, not so that other people can't. It was really odd today for me to uncover them for myself in order to show them to other people.

Karen Frillmann: Michael was a little self-conscious about what aids had done to his appearance.

Judy Weninging: How did that feel?

Michael Calvert: They wanted to ask questions about it, and that was okay. It didn't bother me a bit.

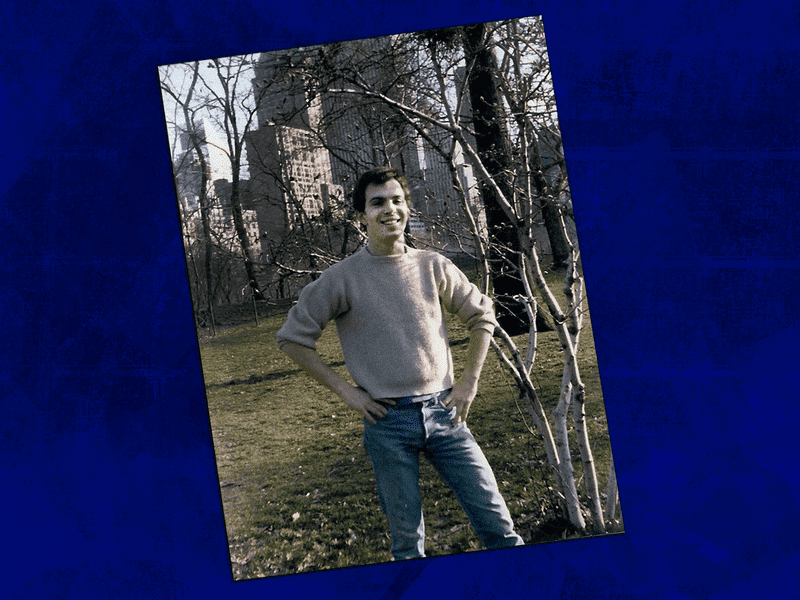

Karen Frillmann: He was still very cute and slight build, very thin. He was Southern. He'd moved to New York when he was 20 years old. That's the thing, he was young.

Michael Calvert: I can show you a beautiful picture of me at age 20.

Judy Weninging: I like your hair long.

Michael Calvert: I like my hair like too.

Karen Frillmann: He'd come from Gadston, Alabama, where he'd been a straight A student.

Michael Calvert: I smoked pot after school with the kids and told them what to study so they could make passing grades.

Karen Frillmann: He'd started acting in local theater. I think he'd been kind of a star in his hometown.

Michael Calvert: Never had a pimple. Then went to the theater every evening and had this whole other group of friends and wild, mystical, free-spirited type friends, and met a lover and things--

Karen Frillmann: You didn't live at home?

Michael Calvert: I did live at home, and I kept my curfew all those nights. Because I was smart, because I was honest, my curfew was one o'clock. They'd rather me be home before that, but they knew I was in the theater. I was in the newspaper every six weeks. It wasn't like they didn't trust me.

Karen Frillmann: They also knew you were in a relationship with him.

Michael Calvert: They didn't know I was in a relationship with this man.

Karen Frillmann: When Michael came to New York, that's what he wanted to do. He wanted to be an actor. He talks about that moment in New York city as being totally life-changing for him.

Michael Calvert: I was wild and it was wonderful and I was not afraid to experience anything and everything when I first came to New York, but I wasn't disciplined and I didn't get what I really came here for as far as acting. I allowed the discovery part of my life to take over and just to do what I wanted to do.

Karen Frillmann: To support himself, Michael had developed a flower business, which you would be walking down a street in the West Village and these little outrageously beautiful flower shops had appeared. It was orchids and bird of paradise and stuff that just, in New York city at that time, which was pretty run down, it was just a gorgeous contrast.

Rick Kitzman: The sad part is, well, there's so many sad parts, but the flower design business was just taking off. By taking off, I mean he was getting some big clients, and it was becoming finally lucrative.

Kai Wright: That's Rick Kitzman. Karen, I got to say, I'm really glad you invited me to join you when you met him because having heard all these recordings of Michael from three decades ago, I was really longing to meet somebody who was close to him.

Karen Frillmann: Yes. Rick came to New York City in the late '70s from Colorado, and they met through mutual friends and started dating.

Rick Kitzman: When you said, "We want to ask about Michael Calvert." When I read that, bam, all of these emotions just came. It was so out of the blue and I was just overcome for five seconds of all these thoughts and feelings and emotions, just thinking about Michael Calvert that came up from that time.

Karen Frillmann: Can you tell us a little bit about him, how you knew him?

Rick Kitzman: It was about '83, '84, my roommate, Sarah Meyers, and I through a party called Well-Read Party. Not only did everybody wear red, but it was also about reading books. It was one of those clever, witty New York things you did in the '80s. Michael came and we just hit it off. He was adorably cute and he was funnier than hell. I grew to just love that Southern charm. I remember the Well-Read Party, we invited practically everybody we knew and Michael did the flowers.

What I remember so distinctly was he brought as many red flowers as he could find. That little apartment was just covered with bouquets of red flowers. We wanted a boutonniere for me, and we wanted a corsage for Sarah, and there's no such thing as a red orchid. The closest is a deep orange, and so that was her corsage. Then he was done putting up all the flowers and I'm going, "What about me? Where's my boutonniere?" He said, "Oh, I didn't forget you."

He took an anthurium and those are those, we called them the little boy flowers because they have blood red more or less leaves with a stamen of about an inch and a half long of bright, gold, yellow. He took one of those and he cut it into a triangle and pinned it to my shirt, and that was my corsage. I just thought it was so amazingly creative. Michael and I, we just had a good time with each other. The flip side was it became really a time of grief and fear and eventually rage.

This friend got sick. I would hear about this friend who got sick. The situation for me became just untenable. It was in '85 that I decided I just had to leave New York because I knew something really bad was going to happen to me. I remember the last time, I'm almost positive it's the last time I saw Michael and I think he was taking me to LaGuardia. We were in his van and he had-- The back was filled with flowers. As I recall, he wished I would stay, but he understood.

I remember he talked about this client and that client and this party and that party. You could tell there was this joy of what he was doing because he found something. It may not have been the reason he moved to New York, but that he loved doing and that he was becoming successful doing it. I think for Michael, that was a new achievement and it was just really fun to be a part of that and to hear his enthusiasm, contrasted with the sadness of leaving each other. I think part of that sadness was I think on some level, it's possible we knew that we wouldn't see each other again.

[music]

Michael Calvert: Is this tape going because I want to say this? I did have a good time when I first came to New York and I'm still having a good time. I really love my life. I think that that makes me a special person, because I don't think there are a lot of people in this world that do. The good times have not stopped just because I hurt. It's really important for me to try to share that with people and to try to help them understand that you can get through difficulty and still have a wonderful, beautiful life.

Kai Wright: What did ultimately happen with Michael and his health?

Karen Frillmann: Judy and I met Michael about a year after he was diagnosed, so he had had a little bit of time to come to terms with what was happening to him, but he was getting weaker and I think sicker.

Michael Calvert: I guess the main problem is just the pain. I try to describe it in therapy. This is more like heartache pain. [chuckles] That kind of pain. Pain that's all over, that's undescribable, that you can't put your finger on it. It just hurts all over.

Karen Frillmann: Another really terrible thing about that time was that some of these young men were shunned by their families. Their parents cut them off. They wouldn't talk to them.

Judy Weninging: You told your mother on the phone?

Michael Calvert: Told my mother on the phone. Well, I had to call her at work. She didn't have a phone.

Karen Frillmann: Michael actually had a good relationship with his parents and his siblings.

Michael Calvert: They loved me anyway without any question, without any hesitation. I think that meant more than anything. They didn't have to say it. I could tell. I was there. I was with them, it's where I told them. The telephone doesn't keep people apart, it doesn't separate people and it really brings people together. I think that even though it was on the phone, I told my mother, she loved me anyway.

Judy Weninging: Your family really cares about you it sounds.

Michael Calvert: Oh yes. I'm very, very lucky in that sense. They're not hiding away. I think they're struggling to stay away in as much as I want them to.

Karen Frillmann: He wanted to be independent. He wanted to continue to take care of himself and live his life. I hear how much he was struggling with the idea of his decline.

Michael Calvert: People poke and pride and especially mentally, not necessarily physically, but they want to know, Well, how can I help you? I'll do anything. You just call me." Well, whose need is that? It ain't mine.

Judy Weninging: You want to stay independent, how long?

Michael Calvert: Forever. Just like you, I would think. Everybody wants to be free and I don't want to be dependent on anyone. I'm liable to die before I get the chance to express a lot of what's inside of me.

[music]

Karen Frillmann: He was 27 years old. He was really just trying to maintain his equilibrium.

Kai Wright: I've thought about this a lot too, as a gay man who came of age just after Michael's generation, is a lot of men his age, they're almost like first generation that show up in a place like New York and San Francisco and Washington DC from wherever they had come and they had to do so much to create their lives in those places. They literally created the gay world in which I now live. They made space for themselves and they were just getting that space. It was just coming into fruition and just when he's got it, to be faced with something like this.

Michael Calvert: [coughs] I'm not crazy about the fact that I have aids. It's difficult and it's a real burden. It's a burden because there's a certain responsibility to helping other people through it because it's such a difficult thing. It's a burden because it hurts. I also don't think that this is necessarily going to kill me before my time. It may and it may not. I'm doing everything I can so that it doesn't, that's part of the burden.

Karen Frillmann: When I met him in '86, he swung between feeling very down to believing that he was going to be a survivor. Of course, there was a quest at that time to find a cure.

Michael Calvert: I fortunately don't think that I'm going to be in captivity forever. There's probably something on the way. I still feel like I'll beat the odds. They say 18 months, I say 19, they say 20 and I say around 24. [chuckles] I don't care what they say. I know how I feel. It's been a year and I feel like I got at least another good year in me and by that time, something should happen that'll help me get through another year, and by that time a cure, and by that time, by that time, by that time. That's how I really think. That's how I really, really, really think. Is that denial? Is that stupid? Is that not recognizing the reality? No, because I do know the reality.

Kai Wright: I just hear such confidence and optimism in the face of this diagnosis, in the face of this disease that I now know would kill so many people.

Michael Calvert: Whatever statistics you quote, I'm going to beat. I'm going to be the person that changes those statistics, I can tell you that right now. No way am I just living 18 more months.

Karen Frillmann: One of the things that taking this tape, listening to it 34 years later, it's partly just the act of remembering and the act of saying that this man walked the streets and contributed to the life of our City. Michael died about five months after we recorded him. He died too young, but that's something we can do is remember.

Judy Weninging: Just for our tape. What I want you to do is just be quiet for one [unintelligible 00:17:13] months out.

[music]

Kai Wright: This is The United States of anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. We'll talk to you next week. The United States of anxiety is a production of WNYC studios. Our theme music was written by Hannah Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Special thanks this week to Christopher Worth, who produced the original version of this segment.

Our team also includes Emily Botein, Regina de Heer, Karen Frillmann, Kousha Navidar, Rahima Nasa, and Jared Paul.

You can catch the live show on Sundays at 6:00 PM Eastern by going to WNYC's YouTube channel, or just stream it @wnyc.org. Listen, if you hear anything that sparks a thought or a question or a story or anything, please do tell us. Send us an email to anxiety@wnyc.org, bonus points if you send a voice note. I'm Kai Wright, you can find me on both Instagram and Twitter @Kai_wright. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.