Keeping Score: Part 1

( Yachin Parham )

Mariah: So, like, we think he’s about to announce, like, who is going to get or not. And I’m so nervous…

ALANA: Mariah Morgan is trying out for the girls’ varsity volleyball team at her high school, Park Slope Collegiate, in Brooklyn.

Mariah: Also it’s very hot in this gym.

Student: We’re all sweating, everybody is sweating.

Mariah: And I’m so nervous about this -- I mean a lot of people seem chill about it, but some of us are a little anxious.

ALANA: In a gym where everyone has to wear a mask, Mariah’s eyes tell you if she’s smiling, or frowning, or following the arc of a ball over the net.

Mariah: I mean, feel like I’ll cry either way, if I’m not on or if I’m not on. Yeah overall I don’t regret it, being here.

ALANA: She’s a junior, and after a year of covid and remote learning, she’s just so eager to get back on the court.

Mariah: Okay so it just ended! And they called my name! So I’m on the varsity team! (SQUEALS!) It was very intense because we literally, I really wanna play, I just wanna be on the team, I dunno.

ALANA: I’m going to try to hold on to the excitement in Mariah’s voice. There’s not a lot of that anywhere these days, much less in high school. But what’s happening in her school, on that team in particular, is exciting. It’s even… historic.

[bring up volleyball sound… cheering]

ALANA: It’s a brand new team, and I’ve gotten to watch as it takes shape. [jaguars cheer] There used to be two athletics programs in Mariah’s school building.

Alex Stevens: Like, we had to play each other, twice! Every year!

ALANA: For more than a decade, they had the kind of rivalry that you might expect between two high schools in the same town.

Alex: It was sort of competing for quote “who’s the better team in the school”

ALANA: And this year, they merged –

Angelina Sharifi: Meshing is like the best feeling ever

ALANA: threw away their old jerseys, put on new ones… started rooting for each other.

[Let’s go Jaguars! Let’s go!]

ALANA: The thing is, rooting for this team means figuring out what it means to win.

Mike Salak: I came into this thinking that I’m going to coach this team like I coach my Black and Latin teams that I’ve had in the past.

ALANA: Because the two programs coming together isn’t just a merger. The other word for it is “an integration”.

Tina Moore: Let’s go, let’s leave it all out there! [cheering]

ALANA: It used to be that one team was made up mostly of white and Asian students, and the other had mostly Black and Latino kids. They played separately for a decade, effectively divided by race and class.

And then, last spring, school administrators announced that it was time to play together. But even the best of intentions didn’t prepare anyone for what happened next.

Over these four episodes, we’ll hear how the decisions made on-high by adults meet the lived reality of students (of teenagers) on the court. And how they feel that heavy burden: the effort to reverse segregation.

[UNITED STATES OF ANXIETY THEME: VOLLEYBALL EDITION]

From WNYC Studios and The Bell, this is “Keeping Score” – a year inside a divided high school building that’s trying to unite through sports. I’m Alana Casanova-Burgess.

[MUSIC SWELL]

ALANA: Before we get to the current merger, to the integration, you’re gonna need background on this campus and how things got to where they are.

Let’s stand on 7th Avenue between 4th and 5th Streets, in Park Slope, Brooklyn. In front of us is this hulking, public school building – neo-Renaissance – brick and stone – big windows – four stories tall. This is the John Jay Educational Campus.

If the outside wall could swing open, like the side of a dollhouse, you'd see FOUR schools, one on each floor, each entirely separate. And they’ve each created an identity to attract students.

[music starts]

All the students walk through the double doors and right into… metal detectors.

On the other side, they peel off, heading to their own worlds.

First Floor:

Students: Cyber Arts! Cyberarts Studio Academy

ALANA: Cyberarts Studio Academy.

Students: CASA

ALANA: CASA for short.

Students: We have digital media and things like that.

Alana: If you could describe CASA in one word, what would it be?

Student: Sustainable, we stay afloat.

ALANA: All the schools have a kind of focus or brand, and for CASA it’s STEM education.

It’s the smallest school in the building, with just over 200 kids.

Student: One word… umm… very Black.

ALANA: CASA’s student body is nearly 90 percent Black or Latino; and almost 80 percent of students come from low income households.

Up the stairs to the Second Floor…

Students: Law! Law! Law! How about Law!

ALANA: …and the Secondary School for Law…

Students: We took law classes.

ALANA: …which, yes, has a focus on law.

Student: There’s like a lot of law stuff on our hallways.

Student: Law is mostly a Black and brown and Hispanic high school.

ALANA: The student body is 95% people of color.

Student: There’s fun things. The teachers is Gucci, some of them, not all of them.

Student: It’s fun but at the same time it’s kind of like chaotic, gotta to keep to yourself.

ALANA: Up another flight of stairs to the Third Floor.

Students: Millennium, Millennium.

ALANA: Millennium Brooklyn. And suddenly you feel a big difference.

Student: I think Millennium is pretty fun.

Student: Extra help if you need it.

Student: It’s a very selective high school.

ALANA: A selective public high school, which means middle school students apply and get in based on metrics like grades.

Student: Millennium, is tight-knit.

ALANA: Of all the schools, it has the most students -- nearly 700. It also has the best pupil to teacher ratio -- and the highest graduation rate.

Student: The people here are very determined.

ALANA: It’s got students from low income households, but far fewer than the bottom floors.

Student: Not as diverse as you’d think.

Student: Very awkward.

Student: Clear tension.

ALANA: It has many more white students than the other schools.

And finally… Fourth Floor: Park Slope Collegiate or PSC.

Student: very very interesting school

Student: They teach a lot about what’s going on socially

ALANA: PSC has an explicitly anti-racist, pro-social justice mission.

Student: We try to fight for equality.

Student: They make sure we’re ok with like most of the stuff that’s going on in our community

ALANA: PSC is similar to CASA and Law in terms of demographics.

Student: It’s very diverse

Student: The diversity is the reason we’d wanna stay.

ALANA: So, there’s a lot going on in this one building.

A few months ago, we teamed up with a nonprofit called The Bell. It offers student journalism programs for public school kids – including some that go to the schools in the John Jay campus. They've been reporting this series with us — recording stories from their classmates … and their own.

[student tape starts under]

ALANA: Sifting through their tape, it’s clear that there’s a serious emotional toll from going to school in a building as divided as this one.

Renika: They’d be like, where are you from? You're not from our school. Go back to your school table.

Thyan: I guess he didn't see me, he just said the N-word. And when I turned around, you should have seen his face, like he’d seen a ghost.

Jada: How would you assume I don’t go there? Is it because I’m Black?

ALANA: Over the years, news outlets have used the friction at John Jay as a kind of case study for the New York City public school system.

So while the sports merger is what brought us to this story, it touches on such bigger issues. Which is why I wanna hand over the next stretch of this episode to my colleague Jessica Gould, who covers education for the WNYC Newsroom.

JESSICA: New York City has the largest public school system in the United States, with almost a million students. More than two thirds of them are Black or Latino; less than a third are white or Asian.

And it’s deeply segregated – by some measures, it’s the most segregated school system in the country.

Many of the city’s schools look like Law or CASA – almost totally students who are Black or Latino. Students at selective schools like Millennium are disproportionately white or Asian.

They also tend to have more advanced placement classes, extracurriculars, and sports.

And what’s interesting about the John Jay campus, is all of that’s happening under one roof. It’s a microcosm.

So I’ve been talking with students from The Bell about what it feels like to go to school here. Lauren Valme is a junior at PSC. And her journey begins really early in the morning…

[alarm sound]

Lauren: My day starts at like 5:50, 6:00, that's when I get up. I'm out of the house by like 7:10.

JESSICA: Lauren lives in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Lauren: I would say it’s mainly a Black community. Because I live right near a mall, the only reason I would see like a white person in the neighborhood is if they're going to go shop.

JESSICA: Her high school in Park Slope is 7 miles away.

Lauren: It’s a whole shift in like demographics. It's like, I went from seeing like all Black and brown people to predominantly white.

JESSICA: Her commute takes an hour and a half, sometimes more.

Lauren: And I have to go drop my sister off to school and then take the 3 train to school and get off of Grand Army and then wait for another bus, the 69. And so I'm with Law kids and CASA kids and Millennium kids, teachers, and they're all trying to get to school. It's a whole process.

[bus sounds]

JESSICA: Stepping off the bus, she sees families with little kids, little dogs and many coffee shops.

Lauren: I just think these people must have, like, a lot of money. Cause these coffee shops are expensive.

JESSICA: She likes to get there early, so she can take a few minutes, sit on a bench, and breathe.

Lauren: I'll sit outside and I'll just watch as the teachers walk into the school, like slowly, and watch as the kids go.

JESSICA: One thing that’s notable about Lauren’s commute is that she travels from a mostly Black and brown neighborhood, to a mostly white neighborhood, only to end up in a school that’s majority Black and brown.

She watches the buses empty out.

Lauren: It's like a big change. So if you turn your head left for just one second, as those kids are coming up from that block, it looks like a whole different neighborhood. And then the neighborhood just like turns back to this being almost fully white.

JESSICA: Only about 15 percent of kids who go to New York City public schools are white – many white families have just opted out of the public school system, going to private or parochial schools instead. Those who stay in the system often go to the same schools.

Lauren: Like the amount of white kids that go to Millennium is a lot.

JESSICA: At John Jay, each school starts at a different time. Millennium goes first, at 8AM. Then the Law kids go in at 8:30, followed by CASA at 8:45, and finally Park Slope Collegiate at 9. That’s when Lauren goes in.

Lauren: And I walk past and go through the metal detectors. I take my time and go up the stairs. Cause there's no point in rushing. And my bag is very heavy. Cause I got my computer in there and my charger and I'm walking up those stairs and I take a break maybe on like the third floor and then walk up again. And when I get to my school, I'm really relieved. And to take, I take like a little, not like a victory lap, but a little lap around the school, just so I go like calm down, reset.

JESSICA: A couple minutes behind Lauren is Mariah Morgan, from volleyball.

[sound of metal detectors]

Mariah: Like basically my outfit kind of revolves on the metal detectors.

JESSICA: Those two rectangular scanners right at the building's front door take up a lot of mental space. Mariah plans what she's going to wear before she goes to bed, editing out items that could ring.

Mariah: I see girls all the time taking off and guys too, who have ear piercings, I see them taking off their jewelry and then walking through and back and through, just taking like every single thing off and disrobing themselves basically to get to school.

JESSICA: Everyday the first adults she interacts with at school are security officers who check each kid on their way in.

Mariah: And like, there's been a couple of times where I've walked in and they'll say like, “good morning,” but I don't hear them. Or I have my headphones in and then they'll just like, walk up to me and be like “I said, good morning.” So it's not the best start to your morning.

JESSICA: Mariah is Black. She told me this story about the time she brought a hair pick to school and the officers confiscated it because they said she could use it as a weapon – to stab someone.

Mariah: So it's very criminalizing to like, have a wand physically wand you, and then you have to put your hands on the table and then you have to, like, lift your leg up and have them go over your shoe.

JESSICA: WNYC ran the numbers a few years ago and found Black and Latino students in the city are nearly three times more likely to go through metal detectors than white students. Officials started installing these scanners in the early 90s; part of a response to shootings and stabbings inside schools.

Advocates for metal detectors say they help keep students safe. And there are real concerns about safety right now. Crime is up in the city again, and there’s been a rise in incidents involving guns and knives in and around schools too. Mayor Eric Adams wants to install more scanners.

The thing is, some people argue that metal detectors perpetuate racial stereotypes.

Mariah: Like, it's kind of telling you that you're supposed to be scared of the kids that you go to school with. That in itself contributes to the demonization of Black and brown children.

JESSICA: In 2015, a Park Slope Collegiate student was wearing glasses that set off the metal detectors. Officers forced him to the ground and handcuffed him.

[protest sound]

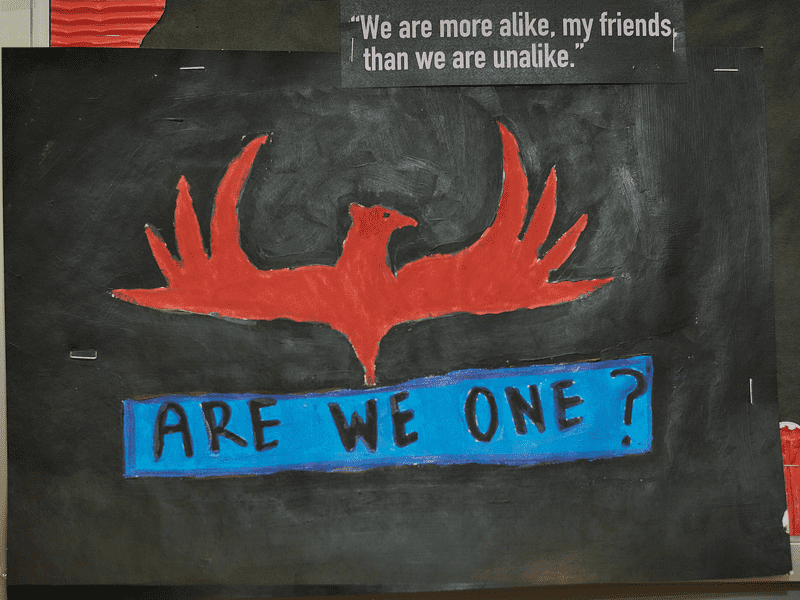

JESSICA: There were rallies, and petitions, the student sued the NYPD. It made the news. And at Park Slope Collegiate, a huge mural was painted about what happened. In it, students are holding signs with slogans like “Scholars Not Suspects” and “Injustice To One Is Injustice To All.”

Mariah: And they're basically pushing off the metal detectors, like off a cliff. So when I do get up stairs from, like, that bad experience of being policed by the officers, and then seeing that mural, it's very revitalizing to me.

JESSICA: Mariah says she feels an activist spirit all around PSC. It’s made her even more passionate about equity, specifically racial justice.

Mariah: I take a lot more initiative in organizing now. If I feel like something's wrong, I always go to my fellow peers in the fight.

JESSICA: Those peers in the fight aren’t just at PSC. They’re across the campus, on all four floors. But connecting with them – in this divided building – is its own challenge.

That’s after the break.

MIDROLL BREAK

JESSICA: This is “Keeping Score:” a year inside a divided school building trying to unite through sports. I’m Jessica Gould.

Renika: I had come into the country on a Saturday and I started school on like a Tuesday, I think?

JESSICA: Renika Jack moved to the US from Guyana and started school at CASA just a couple days later. Growing up, she had ideas about what life at an American high school would be like.

Renika: Cause we had cable, so there’d be like “High School Musical,” and stuff like that. So I came here expecting, you know, a big football field, homecoming dances.

JESSICA: But she was surprised when she arrived at the big brick building in Park Slope.

Renika: It wasn't your usual, typical, bright high school with kids out on the lawn and stuff like that. It was just dull and it was like, oooh, like scary.

JESSICA: No popular kids or slackers gathered in groups on the grass. There wasn't any grass at all, just concrete and, inside, metal detectors with lots of students filing through.

Renika: I saw the white kids. I was like, oh this is an American high school, of course it's going to have white kids. Cause I've never been to school with white people. So I was like, okay, this is cool… But then when I finished with the front office and they showed me to my class, I was like where are the white kids? Like, there's no white kids here, literally none. It was just Black and all the minorities.

JESSICA: Her school - on the 1st floor - is 93 percent students of color.

Renika: I always wonder why, especially CASA don't really have like white people and we just have like Blacks and Hispanics and everything. That question has always sat at the back of my mind.

JESSICA: As she settled in, Renika came to love her school.

Renika: We just come and do our work and try to make the best of all the opportunities that our amazing teachers are actually giving to us.

JESSICA: But she wishes the students got to hang out more with kids from across the campus.

Renika: Unless we have a bake sale on, we'll go up to the lunchroom and interact and stuff like that with them. But we keep to ourselves most of the time.

Noor: Um, do you have friends in the other schools? Do you ever interact with the other students?

Laila: Um, no, I don't.

JESSICA: Noor Muhsin is a junior at Millennium. She’s been interviewing students about the divisions within the building. She talked to Laila Azmy, who’s half European and half Egyptian.

Laila: I don't have any friends in the other schools. I just never have a chance to talk to each other. And we don't have lunch at the same time as most of them. We get out of school at different times. We're on different floors. And it just kind of feels like there's a lot of tension there. Um, and yeah, I don't think about them too much just because I don't have to, but I think that's definitely something that could be changed with more collaboration between the administrations.

JESSICA: Millennium Brooklyn is on the third floor. It’s the one that has far more white students than the other schools at John Jay. But Noor says where she used to go to school, it was way more homogenous. She’s Muslim. Her parents are from Iraq. She grew up in a super white town in New Jersey.

Noor: Kids didn't get me. Like no one pronounced my name correctly. I had people bullying me based on my name, saying it sounded like “floor” and you know, “door.” I had kids tell me, I didn't believe in God because I was Muslim.

JESSICA: For her, moving to Brooklyn and going to Millennium was kind of a relief, actually. She felt like she fit in more.

Noor: I was like, wow, this is great! I've never seen so much diversity.

JESSICA: She says she chose Millennium because of its reputation for strong academics, without being a total grind.

Noor: Oh yeah. I love, you know, I love so much. You can tell the teachers care about each and every one of the students and really wanna help you move forward and they wanna help push you forward, which I just, I love. I love science. I love history. I love English. I love it all.

JESSICA: Noor says the academics are great, but there are real tensions too. Last fall a student tore down and burned a Free Palestine sign and then posted a video on social media. It was deeply upsetting to many of the students across the campus. There was a sense that the administration was slow to respond.

Noor: Our school has kind of brushed it off, unfortunately.

JESSICA: When it comes to interacting with the other schools, she says Millennium is isolated. Her classmates agree.

Atiqa: We basically ignore the fact that we're part of a shared building and it's like Millennium is its own school.

JESSICA: Atiqa Chowdhury is South-Asian-Amerian.

Atiqa: We don't talk about the other kids. And when we see them, it's like, we pretend that they're not there because it's always awkward. Cause it's kind of like accepting that we're not the only people in this building. But when we're on our floor, all we're thinking about is this, like, this is our school. Like, there's no other school in the building, it's just us. That's how it feels like, at least.

JESSICA: Delsina Kolenovic is white.

Delsina: Yeah. I always say that it feels like, like we're in like a business building, like each floor is its own like business. And then we're only focusing on what our business is striving for. And the other schools are like doing their own thing.

JESSICA: So maybe it's not surprising that the separation between the schools can breed suspicion, even outright resentment. Some kids talk about Millennium students having a superiority complex. Plus, they say that staff discourage them from going on each other's floors. And that has a chilling effect. Kids of color who go to the other three schools in the building say they're afraid of getting kicked off Millennium's floor.

Jada Peart graduated from CASA last year. She remembers there was this one time, when she was a sophomore, she had a headache and asked to see the nurse. The school nurse is on Millennium's floor.

Jada: And as soon as we walked through the double doors to the floor, a man who had been patrolling the hallways, I assume, he said where we were going. And I told him that we needed the nurse and he said, and I quote, “Go back downstairs. You don't look like you go here.” And I was just really confused about it because in my head I was like, what? Like, what is that supposed to mean? Is it because I'm Black?

JESSICA: So she left.

Jada: I had to suffer with the headache all day and I couldn't see the nurse. And all of that. It just plays into the idea that our schools are segregated. We're not equal.

JESSICA: The City’s Department of Education told us they’re aware of these problems and their efforts to address them are ongoing: in the past few months, the DOE sent a restorative justice team to work with the school community. And in recent years, the school changed its screening process to reserve more seats for students from low income households but the percentage of Black and Latino students at Millennium has declined.

Kids from all four schools have been organizing through the Campus Council to try to hold the administration accountable – and to improve relationships across the building.

Noor: I am happy I'm in the school, but.I think now that I'm in the mindset of like, okay, well, what can be better? I feel like that's just like, all I'm looking at.

Renika: I mean, we could talk, we could lose our voices. We could scream, we could kick down doors. Let's not kick down doors guys. We could do so many things.

JESSICA: Again, Renika Jack.

Renika: It will never change because at the end of the day, us students, we only have so much power. It takes the people. In higher positions to actually get it done. So we might have to have some pixel fairy dust, something magic, stirring, something for it to happen.

ALANA: Alana here. It wasn’t magic, but last spring, something did happen.

Student: I'm literally in AP lit right now. And we're reviewing the homework and I just didn't do it. So I'm not paying attention. Um, but I got the email just now about the teams like joining together.

Student: I kept hearing like about like the sports teams and stuff, like it coming together, and I didn’t really believe it at first, and stuff like that...

ALANA: The administration had decided: the two sports programs in the building were going to become one. They’d all be the John Jay Jaguars.

Renika: I was like, no way they're really about to merge everybody's sports together. No way that's going to work out.

ALANA: The early reviews were… mixed.

Student: Putting people who might not like each other and telling them to play on the same side, kind of sounded like a recipe for disaster.

Student: I think that us merging shows that we're not, the pretentious image that the other schools have of us.

Student: And just show that at the end of the day, everybody's the same and they just want the same thing.

ALANA: Last fall, as students returned to the building after a year of remote learning, everyone was invited to something called Jaguar Day. A pep rally in the auditorium to bring all four schools together.

Renika: And I was very interested because at first I thought, oh, that should be really fun. So I was trying to get friends to go with me.

[sound up Jaguar Day]

ALANA: Renika and her friends watched as a cheerleader got on the stage ...

Renika: She was screaming on top of her lungs trying to fill the whole auditorium with her voice. And it was like, okay. Wow. Okay!

ALANA: Then a coach came to the front, and tried to get kids to chant this new slogan:

Coach: We are one!

ALANA: We Are One.

Coach: And we only become the strongest bamboo tree in the world by taking care of each other. You are Jaguars!

Renika: I think at the end of it, they were trying to get us to be like all stand up and say from your chest, we are one. And it was like, we are one. The kids were just there like, no, we're not.

ALANA: We are one. That’s the slogan that hangs from banners all over the school now.

It’s as if the building is willing itself to unite. And in the second floor gym, one of the first experiments of the merger is underway:

[gym noises]

That’s next time on “Keeping Score.”

[MUSIC]

LAUREN: “Keeping Score” is a co-production of WNYC and The Bell.

The WNYC team includes: Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jessica Gould, Joe Plourde, Jenny Lawton, Karen Frillmann, Emily Botein, Wayne Schulmeister, and Andrew Dunn.

For The Bell: Mariah Morgan, Renika Jack, Noor Muhsin, Thyan Nelson, Jacob Mestizo, Taylor McGraw, Mira Gordon, and me… Lauren Valme.

Fact-check by Natalie Meade.

Music by Jared Paul – with additional tracks by Hannis Brown and Isaac Jones.

Special thanks to: Afi Yellow-Duke, Rebecca Clark-Callender and Tracie Hunte.

Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.