How Singer Marian Anderson Dominated the Global Stage

( Hulton Archive/Getty )

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and I've got a musical holiday gift for you.

[music]

You're listening to trailblazing singer Marian Anderson. Last year Sony Classical released a commemorative book about Anderson and her legacy including 15 compact disks. Yes, that's those little round shiny things that came between cassettes and MP3s. Anyway the collection represents the entire catalog of Marian Anderson's RCA Victor recordings, 42 years of music from one of the most consequential artists of the 20th century who is maybe starting to fade from our collective memory. The collection prompted us to reflect on Anderson's life story when it came out and this holiday season it feels like a nice moment to revisit that segment.

Let's learn something about Marian Anderson and her music. I called up one of the great voices of American Radio Terrance McKnight, the evening host of WQXR here in New York City who is working on a book about Black artists and the classical stage and he had a lot to say about Ms. Anderson. Terrence, thanks for joining us.

Terrance McKnight: Of course. Thank you for having me.

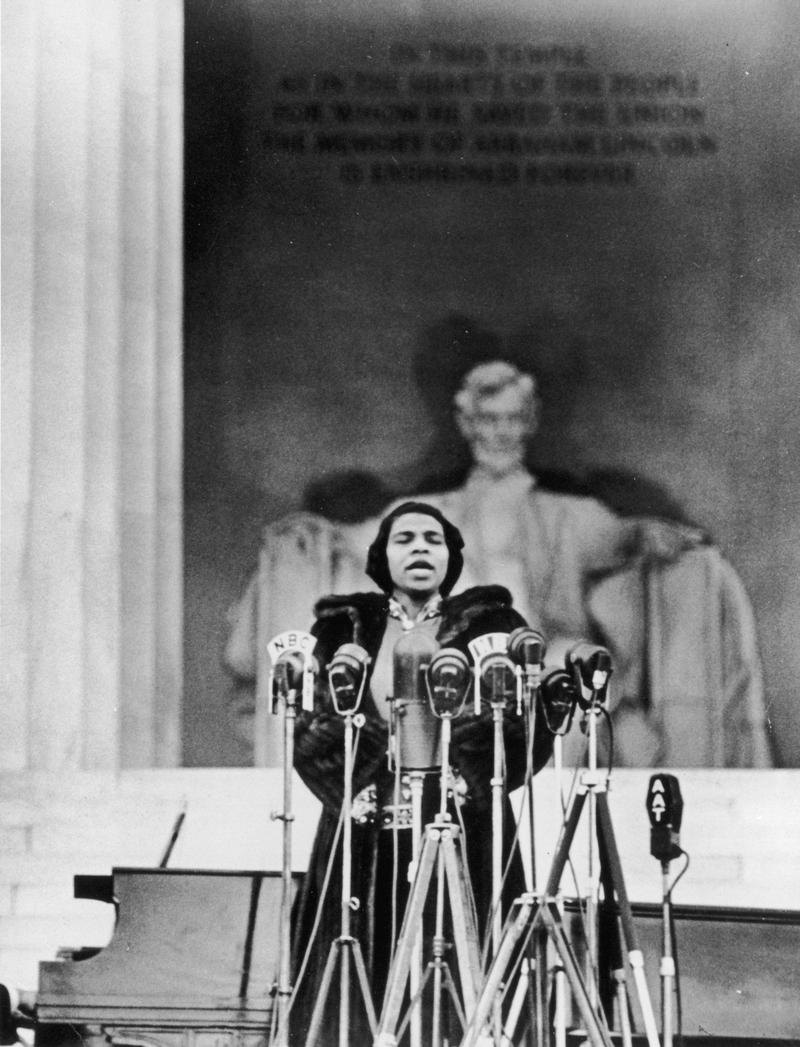

Kai Wright: If people know one big factoid about Marian Anderson it's that she held this famous controversial concert at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939. Remind us of that story. What happened and why was it important historically?

Terrance McKnight: In 1939 Marian Anderson sang on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. 75,000 people came out to hear her sing. It was a radio broadcast. She started by singing My Country, 'Tis of Thee.

[music]

It really shook the country because for someone who at this point in her career was in her 40s, someone who had sung with the New York Philharmonic, someone who had given a debut at Town Hall, someone who had toured throughout Europe and was considered the busiest singer in America, Asia and Europe in the 1930s. She sang at Lincoln Memorial on '39 because she had been refused a concert in Washington DC.

Howard University was trying to bring her and the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her Constitution Hall. As a result the president's wife got involved. Eleanor Roosevelt got involved. She was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She resigned as a result of them discriminating against this Black singer who had conquered three continents. She sang to thousands in Lewison Stadium in New York in 1925. Almost 15 years later she's being discriminated against just because of her skin tone and that was a big deal. One of the listeners that day to that 1939 concert was a 10-year old Martin King Jr. He entered an essay contest at school and he talked about Marian Anderson.

He said, "She sang as never before with tears in her eyes when the words of America rang out over that great gathering. There was a hush on the sea of uplifted faces, Black and white and a new baptism of liberty, equality and fraternity. King went on to say but Ms. Anderson may not as yet spend the night in any good hotel in America. She inspired a young Martin King and she inspired a generation and generations of singers. Man, I think about Sing Sade a few years ago. It was more than a few. I just remember she barely moved yet she commanded the attention of the audience, just pure elegance.

When you look at Marian Anderson that's what you get on stage and off stage, just pure dignity, elegance, and when she opens her mouth to sing it's all there, man. I think that's why she was able to just capture the attention of so many people for so many decades.

Kai Wright: She left the United States fairly early in her career. She'd gone to Europe in the '20s, I gather, in part because she had to because she had tp escape segregation here in order to be a performer.

Terrance McKnight: She got an opportunity. After high school she wanted to go to music school in Philadelphia but was denied. They said they didn't accept coloreds and she got the scholarship from NANM, National Association of Negro Musicians, who provided her with funding as did her church Union Baptist Church in Philadelphia to study privately. She got a private teacher and her talent was just phenomenal and word got out and then she went off to Europe, Man. She was singing so much. I think there was a 6 month period where she sang 120 concerts.

Kai Wright: Wow. Was that typical back then? Was that the work that people did or was she just like an over the top worker?

Terrance McKnight: I think she just loved to sing and there was the opportunity now. The other thing to remember is that when she was born in 1897 and through the first few decades of her career the most potent type of American entertainment was minstrelsy. That's what she was up against. She was the antithesis to how minstrelsy portrayed Black folks. I'd imagine there was a shock as she stood up there and she was able to sing in French and in German and Italian and in English for that matter. Marian Anderson was able to accomplish all of this in the '20s and '30s. Then certainly we can move up to the '50s because up to this point there weren't Black singers singing at the Metropolitan Opera. That was still another barrier that had to be torn down and and she did it.

Kai Wright: In 1955 she becomes the first Black singer at the Met, correct?

Terrance McKnight: That's correct. Interestingly enough she sang the Mask Ball. It's a Verdi opera. She played the character of Eureka which was a witch and Verdi had asked that this person be of color. Typically that role was sung by someone in Blackface. They didn't have to do it that night.

[music]

I think I will say that I believe she was the highest paid singer on stage that night.

Kai Wright: Okay, you get it, Marian. Tell us more about the music itself and her contribution to the American music itself. She started with gospel.

Terrance McKnight: I'm going to say, well, let's call it spirituals because when she was growing up gospel music hadn't really happened. It didn't happen until the late 1920s and '30s. Marian grew up singing those spirituals, that authentic American music that informed jazz, that informed so much of our vernacular music. Now that's what she grew up to and that's what she was so famous for singing. You can't think about He's Got the Whole world in His Hands without going back to Marian Anderson. She really made that tune sing.

[music]

Man, anytime young musicians who grew up in church that church audience is tough. If you've ever had to say an Easter speech or some speech in front of a church congregation. I grew up in a Baptist church so I know those folks. They know real when they see it and when they hear it.

Kai Wright: Indeed.

Terrance McKnight: They want to get you right. Marian Anderson grew up going to two churches. Her mom was Methodist, her father was a Baptist but her father's sister was a singer and she was going to the Baptist church. Her pops would take her to hear her aunt sing. By the time she was 10 years old, she joined a chorus in Philadelphia, and then I believe she gave her first solo in church at 11 years old. If you can stand up in front of the church folks, you learn how to do the job. Oftentimes it was said about Ms. Anderson's performances that they seemed so intimate as if she was singing in a salon or a parlor. I think that has something to do with that small church upbringing.

Kai Wright: In classical and operatic music. What was it about her particular, her music, her musical style, her singing style that was unique or that we need to know to understand her?

Terrance McKnight: For one, it was her range.

[music]

She was a control toe, so she could sing very deep and with a lot of husk, but she could also sing very bright and high. She had just this wide range, but also just if I could explain it, I could do it and I can't.

[laughter]

You just know it when you hear it. I've spent the last couple of days just listening to her just go from Handel to spirituals to Bach to music for the holidays. It's very special. There were folks who said she had the voice of a generation or the voice that you hear in a century and it's true.

Kai Wright: Is there a particular song in the classical and operatic tradition that you think-- Dear listener, if you're going to go out and be introduced to Marian Anderson in her range today, go download this.

Terrance McKnight: If you've ever felt that someone didn't like you, listen to her sing He Was Despised.

[music]

Comes from Handel's Messiah and she'll make you feel a little better. She'll make you feel okay about folks not really caring for you in that moment.

[music]

She really captures what Handel was trying to get across in that music.

[music]

You get the sense that it's personal. That's the thing about her. No matter what she was singing, she made it seem so personal, like she had lived that experience.

Kai Wright: Do you remember discovering her or when she first sort of touched you?

Terrance McKnight: It's hard to remember, but one thing that I found touching is something I learned about her recently. She started that big concert you were talking about in 1939, that was Easter Sunday. She gave her last recital as a singer Easter Sunday, 1965. She didn't leave the stage. She continued to narrate, she did Lincoln Portrait by Aaron Copland, and she continued to advocate for justice and integration and equality. Her nephew, James DePriest became an important conductor in Oregon, in Portland, but he was also heavily involved in New York. He was assistant conductor with the New York Philharmonic, and then he was a conductor with the Symphony of the New World, the first integrated professional orchestra in the country.

That was in the '60s. Marian would go on stage with that orchestra and just show up and she would try to raise money for that orchestra raising money for the cause of integration. One of the musicians he was telling me the other day, he said, "I remember James DePriest conducting Symphony of the New World, and after the concert he said, 'Okay, we're going to go to my auntie's house.'" He didn't think much about it. They got on a train, went uptown, came to this apartment, and he said there was a woman walking around serving tea with an apron on, and when he turned around, it was Marian Anderson.

[laughter]

He said, "But she was just so elegant and she served us tea." This thing about her humility, it just wasn't on stage, you know, was something that she carried with her seemingly in her personal life.

Kai Wright: I have to say, before I let you go, you're working on a book about not only Marian Anderson, but about Black folks and classical music in general. You want give us a tease and when It's coming?

Terrance McKnight: I'm off to a good start. Finishing is something I'll have to ask you about on the side-lines.

[laughter]

I think the relationship that Black artists have to classical music is an untold story. It's not a historical look at Blacks and classical music. It's more taking interviews of folks that I've come across over the years, many of whom are in their 90s and 80s, who were there at that point of integration, who were there also when you had negro orchestras. Hopefully I'll expose some things that folks hadn't thought about. My purpose, man, is to find a way forward that's more inclusive. When we go to the concert hall, we see all of our culture up there together and not this hierarchy of culture and certainly not just Black composers or Black artists in February or March, [music] but something that's more reflective of what America can be.

Kai Wright: Thank you so much for this time, Terrance.

Terrance McKnight: Kai, thanks so much for having me. Talk about what I love talking about.

Kai Wright: [music] All right. Terrence McKnight hosts the Evening Show on WQXR here in New York City. That's our sister station. You can catch his show every weeknight at 7:00 PM Eastern.

Kai Wright: [music] Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. You can follow us wherever you get your podcast and join us on Instagram @Notes with Kai. Listen, if you didn't catch the show last week, we did this awesome thing where we invited listeners to call in and live curate a Notes from America Holiday playlist. If you're looking for music to get you through the next few weeks, do check it out. You can go to our website and click on any other recent episodes to find a link to the playlist, or you can just search for it on Spotify. One more piece of exciting news, next month for the Martin Luther King Day holiday, we are going to record our show live from the stage of the famous Apollo Theater here in Harlem.

This is part of an annual event produced by WNYC and the Apollo to honor MLK Day. For the first hour of it, I'll be hosting conversations inspired by the song Young Gifted and Black. The event is Sunday, January 15th. Tickets are free. You just have to RSVP to get them. They'll be available starting in the new year on January 2nd. You can get all the details at wnyc.org/mlk2023. Jared Paul does the music and mixing for our show. Editing, producing, and reporting courtesy of Karen Frillman, Vanessa Handy, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar and Lindsay Foster Thomas. I am Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us tonight and happy holidays.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.