‘Ethical People Can Be Effective’

Kai Wright: This is the United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

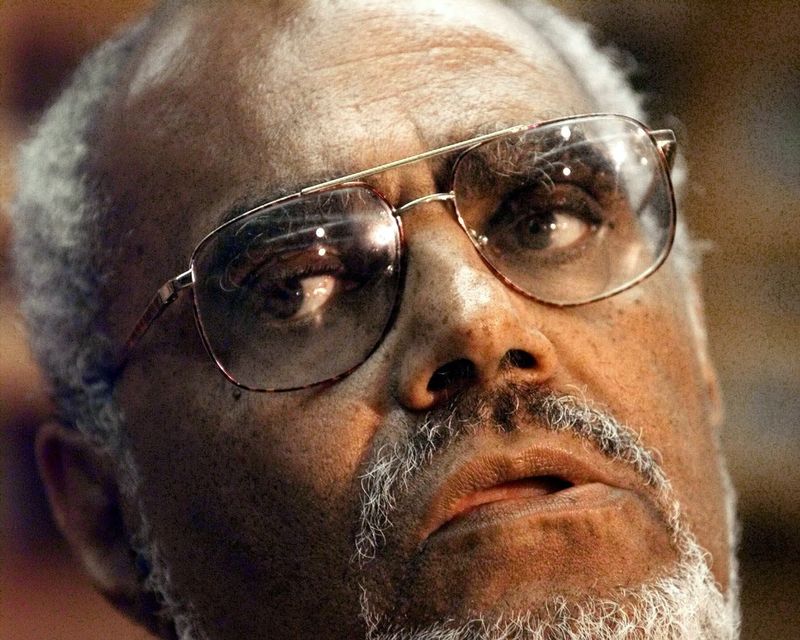

Charles Blow: Robert Parris Moses was a civil rights activist, education advocate.

Eleanor Holmes Norton: What made him stand out was his calm courage.

AMBI: Dogs barking, police whistles.

Bob Moses: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, they seek radical change in race relations in the United States. The world is upset, and they feel that if they are ever going to get it straight, they must upset it more.

Cori Bush: Our America will be lead not by the small-mindedness of a powerful few but the imagination of a mass movement that includes all of us.

N’Tanya Lee: These kids need to be at least at this benchmark because they don't have a safety net.

Protester: You can turn your back on me but you cannot turn your back upon the idea of justice.

Kai Wright: Welcome to the show, I'm Kai Wright. Harry Belafonte tells a story in his memoirs that for me, perfectly captures a part of the civil rights movement that is too easily forgotten or maybe erased. The story is set in 1963 in Greenwood, Mississippi. This is right as things are really coming to a boil in the south because a group of young activists are forcing the issue of voting rights. That group is the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or SNCC.

These are the kids, college students, who sat in at lunch counters and rode buses across the south and generally put themselves in grave danger in order to dramatize the fight against segregation. It's John Lewis and Marion Barry and Stokely Carmichael and all those names, and Harry Belafonte was an important source of funding for their work. Anyway, Belafonte tells this story about how at one point in 1963, SNCC's voting rights campaign in Mississippi was in particular trouble. A lot of people were in jail, they were out of money, and it was kind of an emergency situation.

Belafonte, back here in New York, he grabs his friend Sidney Poitier. They gather up tens of thousands of dollars in cash from other celebrities and rich people here and they personally fly the money down to Greenwood to hand-deliver it to SNCC. Well, the Klan gets wind of this, and a bunch of them meet the two stars at the airport and chase them through the night, shooting at them, trying to kill two of the most famous people on the planet. Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier are at that time, just megastars like Beyonce level stuff.

White people in Greenwood, Mississippi figure, "Whatever, we can just kill him." That is the level of violence and impunity SNCC's activists were facing because they were trying to register Black people to vote. I always tried to remember that. One of the most consequential people behind this heroic activism died last week at age 86. I suspect a lot of people didn't know about him until his obituaries hit the news. Bob Moses was a New York City native, grew up in Harlem. He was the architect of so much of what went down in Mississippi in the early '60s.

His theory of change and his personal story of change both has so much to teach us today. How do you face resistance so massive and so unabashed that any challenge to it feels like it's futile? What do you do when every daring step towards progress leads to even greater retrenchment? In an environment like that, how do you even know if and when you've changed something? All resonant questions right now, and we're going to spend this hour reflecting on them through the remarkable life of Bob Moses, a quiet, largely unsung hero of American history.

I'm joined by Charles Payne, a professor of African American Studies at Rutgers University and one of the great chroniclers of the civil rights movement. His 1995 book, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement is considered a definitive text. Here's what we're going to cover here. He knew and he worked with Bob Moses and studied his life closely. Charles, welcome. First off, my condolences for the loss of your colleague.

Charles Payne: Thank you for that and thank you for having me this evening as well.

Kai Wright: That story I just told about Harry Belafonte, as I understand it, Bob Moses was kind of the person on the other end of that cash delivery, the Klan was trying to stop. Is that right? More broadly, can you just help us further understand what it was like on the ground in Mississippi, as Bob Moses and his colleagues began launching this voting rights movement there, how common was the violence of it all?

Charles Payne: I don't actually remember who was on the receiving end. It quite likely could have been Bob, but it's also quite likely that he would have given up the honor of meeting two big stars to someone else. That would just have been a part of his teaching style. What I do remember is Sidney Poitier, who was not as deeply immersed as Belafonte in the movement, told Belafonte something like, "If you ever invite me down to one of these things again, I will kill you."

Kai Wright: [laughs]

Charles Payne: Words to that effect. As to what the situation was in Mississippi, and let's say 1960 when Bob went down for his initial visit, grim is a good word to start with. You've got about 5% of the Black population registered to vote. Most of them were not actually-- great many of them, I should say, were not actually voting. The violence was extreme at that time. In fact, for the prior six years, starting in just about 1954, with Brown v. Board, Mississippi had gone through a period of intense repression.

If you attempted to register to vote, if you signed up to have your child go to the segregated school, it's likely you were going to have your name and address published in a paper for some period of time. Likely that you'd be evicted if you were a sharecropper, your mortgage would be called in if you had a mortgage. Almost certain you were going to be fired, your home could be bombed, and people were assassinated. The Klan circulated a death list in the middle '50s. They were quite serious about that.

Kai Wright: I want to underscore that just for a second there that there was a death list. I mean, we know of a handful of people who were-- the big names that were killed, but a lot of people were actually assassinated in acts of terrorism.

Charles Payne: That's right. Just off the top of my head, there were eight names on the death list in 1955. By the end of that year, five of those names had either been killed or run out of the state. One of those killed was George Lee, way up in the Delta at a town called Belzoni, who had built a really strong I think, 600 members in his NAACP chapter. He was a minister, he was shotgun to death one night just sadly, before service. His friend, Gus Courts who took over the leadership of the NAACP after Lee was killed, was almost immediately shot, seriously injured, survived but he left the state and did not come back for the rest of his life so far as I know.

That just captures what it was like and the amount of publicity for these things. While it was greater than it would have been 10 years earlier, it was still nothing like a national story. One of the reasons there was such impunity is the nation was simply not paying attention.

Kai Wright: That's the world that Bob Moses steps into in 1961 when he comes to Mississippi. If people have learned one thing about him since his death last week, it's probably his passion for grassroots organizing. Help us understand his thinking about leadership. In your book, you write that one of the reasons Moses joins SNCC instead of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which is, of course, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s organization, was that he connected with SNCC and Ella Baker, in a way that he didn't connect with King.

What separated the two, SNCC from SCLC, in their terms of approaches to activism?

Charles Payne: Back up, sir.

Kai Wright: Yes, please.

Charles Payne: I think you're going a little too fast. I want to go back to the issue of what Mississippi was like when Bob stepped onto it because it wasn't all gloom and doom. The other side of that story is that movement infrastructure-- I'd say the movement began moving into a new phase almost immediately after World War II, the infrastructure that people began to create then despite all that violence. Medgar Evers was still the state Chair of the NAACP. Bob says there were 20 NAACP leaders around the state.

The work that he did, was built on the work that they had done and built on their capacity to pass on to him what they had learned from fighting alone without any recognition nationally, from fighting alone against the beast in Mississippi. Indulge me for one second, while I read something that Bob said. "One of the things that happened the movement was that there was a joining of a young generation of people with an older generation that nurtured and sustained them. It was an amazing experience.

I've never before since had that experience where it's almost literally like you're throwing yourself on the people and they have actually picked you up and gone on to carry you so you don't really need money. You don't really need transportation. They're going to see that you eat. It's a liberating kind of experience." When Bob tells his story, he wants to put emphasis on, well, not Bob Moses came and things change, but Bob Moses came.

He came into communities of support, despite all the danger, despite all the costs and those communities of support ought not be written out of his story.

Kai Wright: I thank you for that and I feel like it connects to this broader point that well, maybe that's the backstory to how he shows up and develops a, if we can call it leadership, leadership style rooted in that idea. I do want to ask you about that distinction there about who he was drawn to since you did mention in your book, versus that he's drawn into this part of the movement versus into the SCLC. Stop me if that's a false divide.

Charles Payne: No. That's accurate. He went south to volunteer to work with SCLC. He got the SCLC didn't have anything for him to do actually. He's just hanging around. He also found the style of many of the SCLC ministers to be top-down bureaucratic. They were invested in issues of image and issues of what people follow them in a way that he did not care about. At the same time, Ella Baker, who was on her way out then from her tenure at SCLC and who would become the mentor to Bob in particular, but to SNCC in general.

Ella Baker, he found incredibly interesting and she was interested in him and that's one of the things he always says when he talks about how he drifted into SNCC. Ella had a personal interest in him and his growth, his development, but he did not get on the SCLC side. Then at the same time, Ella's conception of humanistic politics of a politics based on the dignity of the "common" man and a woman, that phrase common in quotes, dignity-based politics, I think was just philosophically attractive to him.

Kai Wright: Let's hear Bob Moses talk a little bit about this organizing perspective himself. Since you quoted from him. Let's hear him in his voice. He spoke with reporter Alexandra Starr a couple of years ago, and she shared some of the tape of her conversation with us. We'll get to hear bits of it throughout the show. Here is Bob Moses explaining how he and SNCC thought about their work in Mississippi in the early '60s.

Bob Moses: I think of it as an earned insurgency then and it's really crucial. On the one hand, you had to earn it for and from and with the people you were working with, the farmers and the day laborers. The only way to do that, I think was that every time you got knocked down, you stood back up and kept going, because there's no way to talk about what you were going to do or what could be done. They had been talked to death. They weren't listening to speeches about what might or might not be done, but they did respond to actions to the SNCC field secretaries and their insistence on standing back up.

You won over them and that's a big thing because they have much more at stake, their families, their economic arrangements, their lives. This is real. This is not play.

Kai Wright: This is not play coming up. We'll talk about how and why Bob Moses left his promising career as an educator in New York and went to face violence in Mississippi and later his answer to what he called sharecropper education. That's all next, stay with us.

[music]

This is the United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright and we are reflecting on the life and work of Bob Moses who died last weekend at age 86. He's one of the more unsung heroes of the civil rights movement. He was the architect of so much of the daring activism that happened in Mississippi in the early 1960s, which arguably led directly to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. I'm joined by Rutgers University, professor Charles Payne, whose book I've Got the Light of Freedom is arguably the definitive history of the Mississippi Movement.

Charles, I want to talk about how Bob Moses came to the movement in the first place. It seems like he was this brilliant young academic who was really searching for what he wanted to do with his life. He was getting a PhD in philosophy, I believe at Harvard, but he left that path. I want to play another clip of what he said in his interview with Alexander Starr. Here's what he said a couple of years ago about that choice.

Bob Moses: The comfortable life in the white institutions that were at that point, experimenting with having their first African-American do this, do that, that didn't appeal to me at all. I had no real interest in that. I didn't know what I would do, but that wasn't going to be it.

Kai Wright: Charles, help us understand these pre-SNCC days for Bob Moses. As I said, he left Harvard. He came back to New York. He started teaching at the prestigious Horace Mann School in the Bronx, which was still all-white. What was going on for him at that time?

Charles Payne: The part of that history, that part of his life that I know best has to do with the relationship between Bob and his father. His father was a janitor most of his life. One of the buildings he was responsible for cleaning at one time was an armory of which his brother that is Bob's uncle was the commanding officer. He's in this situation where he has, if you will, the bottom-most job in the building, and his and his brother that is the father's brother, is the most important. You can imagine how that makes people think about social structure, about inequality, and their position in the world.

What Bob says is that-- Actually, I think one of his favorite memories of growing up is that his father took him on his rounds of Harlem when his father was going out to visit and just shoot the bull with his friends. He takes Bob with him. After each conversation, he debriefed that conversation with Bob. Why do you think that person said this and didn't say that? He creates this habit of mind where he has Bob looking at things from multiple perspectives. At the same time, his father always wants to come back to the perspective of the person in the street.

The perspective at the bottom. What did what we talk about mean for the folk around us in Harlem? I think that was virtually hardwired into Bob. A deep, profound connection and a respect for the people who are at the bottom of the social structure and some of that, he gets from his father. Then of course he falls under the tutelage of Ella Baker and she formalizes gives words and theories and connection and history to some tendencies to make a difference that I think his father in part had instilled in him.

Kai Wright: What's interesting in there when I hear you talk about it too, is in that story with his father, I hear him teaching him to listen, which it's part of organizing and leading in politics that I don't think we think about.

Charles Payne: No, but I think Bob took it to a notch. [laughs] He could listen to you and he could make you listen to yourself differently by his strategic silences sometimes by the questions that he would ask sometimes. Boy, you talk about a really active listener, stories after story about Bob sitting through these hours long, if not days long SNCC meetings and just listening to people. Being able then to put everybody's ideas into a framework that helped even the people who had said the things he was talking about. Yes, listening with respect was a huge part of his teaching style.

Kai Wright: I want to bring in somebody who was one of Bob Moses's white students at Horace Mann in these early days, Gary Benenson is today the project Director of City Technology, which is a collaboration of the Schools of Education and Engineering at City College of New York. They work with elementary school teachers in New York City public schools. When Gary was 12 years old, he was Bob Moses' student at Horace Mann. Gary, thanks for calling in.

Gary Benenson: Hi, how are you?

Kai Wright: Very good. I wonder if you were just listening to what we were talking about in terms of Bob Moses' style of being such a listener at the time. I wonder what do you remember of your old teacher and what he was like at that time? I wonder, because he sounds in the tape we played like he was dissatisfied with the world of these elite white schools that he was teaching in and so I just wonder what that was like being his student.

Gary Benenson: First thing is that he didn't light on that he was dissatisfied, at least not to me. When that became clear to me was in the last year that he was there, which was '60, '61 just before he went to Mississippi, he began recruiting students to support SNCC. At that time, there were the sit-ins that had just begun across the south. I remember Bob selling buttons to and involving us in thinking about the student sit-ins, the button would support students sit-ins.

That year, I was very close to him and we talked a lot about politics as well as mathematics and lots of other things. I was attracted to him because I realized that of all the teachers that I had ever had or have had since he was the most interested in teaching and in students. I had an immediate connection with him. The last two years that he was at Horace Mann, he decided that I didn't really need to learn the regular math curriculum. He took me aside with one other student for one year, and we were in a class by ourselves and he decided that he was going to teach us college math.

I think that he was doing an experiment to find out how far he could push me because later I heard him say that I was the best student that he ever had. I said obviously, he was the best teacher that I ever had.

Kai Wright: Can I ask you about-- and we're going to get here in a bit to the incredible work that Bob Moses eventually did on math teaching in general. You mentioned him passing out the buttons and talking to students at Horace Mann about the sit-ins and politicizing, thinking about politics, which right now, however, what 50-some odd years later would be wildly controversial. I just wonder how that was received at the time, how did the white students receive him when he did that?

Gary Benenson: Well, we had a small group of students that was called-- these were the days of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. There was an organization in New York called Fair Play for Cuba. We organized a committee at Horace Mann, a club that supported Fair Play for Cuba. Bob Moses of course, was our faculty advisor, imagine then. Anyway, we were going to March in a-- there was a parade on 5th Avenue around the theme of Fair Play for Cuba. We were going to march with a banner that said "Horace Mann School Cuba Action Committee supports Fair Play for Cuba" something like that.

We were called one by one into the office of the Dean of this school. He told us point-blank that we would be expelled if we did that. I think he said to me, "If you don't like it in this country go back to Russia." I remember thinking, "I can't do that because I was never there." We were at odds with the administration of the school. Bob made a very determined effort not to tangle with them because he was-- I think at that time-- He later told me that he was grateful to them for hiring him when he needed a job.

Really well though, he disagreed strongly with the philosophy of this school, he didn't want to say anything negative about the people that ran it.

Kai Wright: Gary, I'm going to have to let you go in a second, but briefly, I know then in 1961, you and your father and your brother went down to Mississippi to visit Bob right after he'd gone down there.

Kai Wright: Can you give me your brief impression of him at that time once he had arrived there, did he seem different? What did you take from it?

Gary Benenson: When he first went to Mississippi he stayed with a guy named Amzie Moore who was another unsung hero, I would say, of the civil rights movement. Amzie was much older as a veteran of World War II. We visited them, and Bob was new in Mississippi. Amzie was teaching him what it was like there. I remember Amzie more being a much more commanding presence than Bob. The other thing that we learned was how repressive and segregated it was because the only place that the five of us, this was Amzie, Bob, myself, my brother, and my father--

The only place that we could eat, all five of us was at the luncheon out of a gas station that Amzie ran. He had learned to do that by being a student at the Highlander Folk School, where they taught Black people how to run a business. That was how he became independent more or less of the white power structure. They also receive death threats. Amzie did because in town had seen us all driving around in the same car. Obviously, that was something that wasn't done.

Kai Wright: Well, Gary, I thank you for sharing these memories and thank you for the work you've done since you came under Bob Moses' tutelage.

Gary Benenson: I appreciate it.

Kai Wright: Charles, to fast forward just a little bit, I know you don't like it when I do, once he's down in Mississippi there, over the next four or five years they're doing these harrowing voter registration drives. As you've talked about is incredibly dangerous and violent. It's not really working in terms of the number of people that are getting registered. The federal government is not responding and they come up with the idea of Freedom Summer, which I gather was mostly Bob Moses' idea. Can you explain what was Freedom Summer and why they did it?

Charles Payne: I'll get there eventually. I want to go back again. It is crucial that we think of this as a story about local Mississippians. Once you have jumped into Freedom Summer, then it's a national story. It's important it's crucial and all of that, but it is also a part of the movement mythology. Let us go back to Amzie Moore. Amzie Moore from Cleveland, Mississippi in the Tulsa is drafted. He serves in the Pacific in World War II. He comes back. I think it's something like 88,000 Black veterans returned to Mississippi after the war, Amzie among them.

A great many of them had a new sense of entitlement. They were not going to settle for what they had endured before they went. Amzie immediately began organizing something called the Regional Council for Negro Leadership, which did economic boycotts. I'm talking now probably early 1950s, very early 1950s. Amzie has a history of 10 to 12 years of hard-nosed organizing in one of the most dangerous parts of the south before he meets Bob. Without the base that Bob builds-- Bob is always emphasizing without the network of supportive people that folk like Amzie created, Bob would not have been able to do freedom somewhere or anything else.

Highlander too is a crucial part of movement history. It wasn't for so much for teaching Black people to run businesses. Although I can think of cases that it did that. It was for teaching anybody in the south how to make social change. If you were a white Appalachian and wanted to know how to start a union in a coal mine, you went to Highlander. Rosa Parks was there six or so months before she went before she initiated what became the Montgomery Bus Boycott. A ton of SNCC folk went to Highlander.

So, Highlander plays a crucial role and creating a multi-issue movement culture in the south, and then nurturing folk who are going to be really crucial leaders in all kinds of ways. Freedom Summer was your question, I think.

Kai Wright: I agree with you. It's very prime. Just mindful of my clock is my problem.

Charles Payne: I understand, I understand. I’m going to let you run your show any minute now. [Laughs]

Kai Wright: I want you to run it, Charles. You're doing a great job. The point I was making is that, absolutely, we have all of that build up to this moment because as I understand it, all of that was making local progress, but the violence was beating it back and the federal government was ignoring them.

Charles Payne: That's exactly right and two killings, Herbert Lee in 1961, Louis Allen, 1964, both of whom had been connected in different ways to the work that SNCC was doing around voter registration. Became particularly emblematic in the SNCC world. The premise of Freedom Summer was that we had been beating our heads against white supremacy in the state. At this point for two or three years, we've gotten only a handful of people registered, and many people have been killed.

Heaven knows how many homes and churches and schools have been bombed. The federal government is still maintaining they do not have the authority to do anything about it. The National Press Corps is sometimes interested if a celebrity comes down for demonstration or something. If there's violence, but there no consistent national media coverage of the disenfranchisement of Blacks, just the disenfranchisement of Blacks in the south. The idea behind Freedom Summer is if we have to stop violence, if it's very, very clear that Black lives do not matter in this country, then we have to bring some people down that do matter.

Bring some people down that the country cares about and the country will protect them and in protecting them, maybe they will also protect the movement. Well, it worked. When I say it worked I meant, boy, the federal government, particularly after the assassination of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Mickey Schwerner, three civil rights workers.

Kai Wright: Two of them were white we should spell out.

Charles Payne: Right. Schwerner and Goodman were both white. Goodman was a New Yorker, I'm almost positive. After they were assassinated, the federal government made the Jackson FBI Office, the largest one in the country, they sent like 250 military personnel to look for the bodies. They turned on a dime. The feds after the summer began enforcing the law, if you will, but began protecting the lives of voter registration workers in a way that it never had before. They dramatically infiltrated the Klan. They got informants in Klan chapters all across the south and Mississippi.

Hoover, who was absolutely an enemy of the movement, but under pressure from Johnson, Hoover sent every police chief in the state of Mississippi, a list of the people who were on the local police force, but also in a local Klan. Hoover tells the police chief something to the effect that, "Either you get rid of these people or I will do something about it. I will go public with this." The federal government for the first time in the 20th century, took an aggressive stand against the violence that had been the underpinning of white supremacy. It took a while, but it made a huge difference in the ability of the movement to move.

The other side of that though, is that it was embittering. Look, there wasn't any news to Black activists that Black lives were not valued in this country in the way that white lives were valued. They knew that, but to have it thrown in your face this way, to have the country go into virtual shock when two young white heroic, young white men who were killed. Everybody understood everybody believed at least, had James Chaney been alone that night, that story would never have become a story. It was also embittering, partly because of that, and partly because of other things that happened.

Bob said that one of the consequences of Freedom Summer was that the nation lost contact with a generation of its most idealistic youth for decades. That is to say, those people who identified with the movement lost faith in liberalism, lost faith in national institutions, including the Democratic Party, lost faith in moral suasion.

Kai right Lost faith in white allies too. Is that right? That is how I took some of the reading of Bob Moses'. In this moment he decided I just can't anymore with this trying to build with white people. Is that fair?

Charles Payne: Well, I don't know. I've never heard him say that. It's entirely possible. There was a lot of anger at that moment. It's very difficult for movements to take in a lot of people at one time, without changing the culture. Many white people came south and stayed after the summer, that SNCC became a very different organization. Partly for that reason and partly because outsiders always bring to the movement some degree of the virus the movement is trying to fight. In this case, some of the white students who came down and they came overwhelmingly from elite colleges had elite attitudes.

They thought that having had a course in sociology, they could direct the Mississippi Movement better than the people who came from Mississippi. Some of them, obviously, thought people in Mississippi were victims and that they needed to be led. Not everybody, but some folk brought the kinds of attitudes that the movement found extremely problematic. That is a part of what happened but some of it is just that the folk who had made the movement from '61 to '64 wanted to do it on their own. They did not want to be dependent upon outside help, but they wanted to craft social change with their own hands.

Kai Wright: We're going to have to take a break. But when we come back, I want to tease out what the lesson of some of that is. I want to talk about what happened later in Bob Moses' career, when he decided to turn his attention to the movement for racial justice, through math. That's next, stay with us.

[music]

Kai Wright: Welcome back. This is the United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright, and we are reflecting on the life and legacy of Bob Moses, one of the more unsung heroes of the civil rights movement who died last weekend at 86. I'm joined by Rutgers University Professor, Charles Payne, whose book I've Got The Light of Freedom is really the definitive history of the Mississippi Movement. Charles, before we turn to the Algebra Project, now I just want to quickly ask you to help us tie up what we were talking about before the break.

It sounds like there's so many lessons in that for today's movements, in this disillusionment and the rushing of people into the space that brought their own entitlement. Just quickly, what would you take from that for today?

Charles Payne: One, what happened at that time was that despite all of the problems, Freedom Summer contributed leadership to the Free Speech Movement on college campuses, to the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, and to the Second Wave of Feminism. That is to say, I think the first lesson that I want to take is that movement did not stop because people did not always agree with one another. Folk found ways to make change despite all the turmoil and all the change that was going around them. I think the other thing if I could say just one thing about a very complicated and complex issue, how do outsiders best contribute to an insider movement?

How do allies present themselves? I think a part of it, the one thing I would say is you cannot come into the movement expecting gratitude. Some of the volunteers who came down expected that because they came down, they were entitled to a certain kind of status inside the movement. That sense of entitlement is in many ways exactly what the movement is working against. That is one I think, piece of advice to caries across time and situation.

Then the other, which is a corollary tool is be about the work. If you're the ally, nobody has time for your problems, nobody has time for your projects, for your priority. Focus on the work as defined by the people who are most affected by the program. That orientation towards work is a huge part I think of the impact that Bob had on folk. The fact that he was always centrally focused on the work that means the most to all of us.

Kai Wright: In 1982, he turns his attention to the Algebra Project, which is what he spent the last half of his life working on. In our short time left, I want to focus on that. This was his effort to teach math as a form of critical thinking to solve our problems as citizens and to deal with what he called sharecropper education. I want to bring in another person who knew Bob Moses in this part of his work. Kate Belin teaches math at the aptly named Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School, which is a small public high school in the South Bronx.

She oversees the Algebra Project there where she got to know Bob. Kate, thanks for calling in.

Kate Belin: Thanks so much for having me.

Kai Wright: Kate, can you help us understand, I gave us a quick synopsis but help us understand what the Algebra Project was and is?

Kate Belin: The idea is that students should graduate high school prepared to take college math for college credit or be able to pursue any career of their choosing without math being an obstacle to pursuing that work. When he won the MacArthur Genius Award in 1982, as you were just saying, he was recognizing that there are skills that we're going to need for jobs that have not yet existed on this dawn of the technology age. Can we think of another subject that feels like a gatekeeper in the same way that math does?

How many people would say, "I'm interested in this, that, or the other career, oh, but the math"? If we don't do something about this problem, then we're going to have sharecropper education in the sense that students will be locked into work that has been pre-assigned to them, rather than being able to pursue any career of their choosing.

Kai Wright: Is the idea primarily about the skills you're learning in math, or is there something more to it as well? Help me connect this piece of his work to his citizenship work that he set out to do.

Kate Belin: I think the answer there is exactly about how things are being taught rather than what specifically is being taught. I guess I'll jump to just what Dr. Payne was just saying about Mississippi and maybe highlight Fannie Lou Hamer herself for a quick moment. As Bob recognized when he went down to Mississippi, but if you move the needle on Mississippi, you'll move the needle on the nation. He said Fannie Lou Hamer had Mississippi in her bones.

That when she spoke and gave what has come to be known as her "I question America" speech at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, the reason President Johnson intentionally interrupted that broadcasting is that Fannie Lou Hamer's testimony scared him. Bob knew that the power of her testimony was even more scary to President Johnson than that of Dr. King because it was coming from the place, as Dr. Payne just said, of the work being focused on the people who are most affected by the problem.

That's the connection is that we're teaching math or really organizing that we're learning how to center the voices of our students. That we, the Algebra Project can talk all day and all night about mathematics as an available organizing tool for access to full citizenship in the 21st century. Ultimately, that message is only as powerful as the degree to which it is felt and acted upon by the students themselves. That's the part we have to-- how to do that's-- long for the end of your program here. That's the idea, right?

Kai Wright: I hate to drop it on you with just a couple of minutes but how do you do that? Thinking about there at the Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School in the South Bronx, what's one thing that you can think about that brings these ideas to life right now in how you guys are doing your work?

Kate Belin: I'll set a little light on the importance of starting everything with a shared human experience. Some of us may be familiar with Bob's book Radical Equations, which also lays out a major mathematical unit of study of the Algebra Project, the Trip Line. It's a unit where students are learning the real number line. How you teach it is you start by taking a trip together. The case there was developed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Bob was at the time, taking a shared trip along the piece together.

Documenting that work and really using for a longer period of time than any of us teachers are comfortable with. Patience was a huge theme earlier in the episode, Bob's ability to listen, to wait. You stay in that experience of going on a trip. A trip on the subway works perfectly because there's stops and directions. If you can't start any mathematical project with a meaningful experience, then we should probably reconsider if it's worth teaching in the first place. That things have to start with experiences that are meaningful, that are relevant, and that we are participating in together.

Kai Wright: It certainly sounds like the organizing strategy that Charles was describing. Kate, thank you so much for sharing these memories with us.

Kate Belin: Oh, thank you so much for this episode.

Kai Wright: Kate Belin teaches math at the aptly named Fannie Lou Hamer High School in the South Bronx. Charles, as we wrap up, you wrote a tribute to Bob Moses in The Nation, which you talked about the "fullness of the man". Just even in this conversation, we have gone through so many things that he touched in his 86 years. Some of that fullness, what is that fullness, and what do you see as his legacy?

Charles Payne: I think right now, the way I would answer that his fullness had to do, his attraction to so many of us had to do with the fact that we need to believe that ethical people can be effective. He was deeply ethical and he made deep changes in the world in more than one theatre of change. That's the part of what I would mean by the fullness. Also, I want to say that the idea that was, I think, even embedded in the way in which you frame the question, how does he become a math teacher after a movement?

People assume those are fundamentally different things. Before I never knew him to think of it that way. I think it's an impoverished conception of the civil rights movement that sees the teaching of math as not part of that. Bob's position was that Mississippi in 1961, the barrier to full participation is exclusion from the vote. In our times, just as in the 19th century, you weren't a real citizen if you could not read or write, by the middle of the last century.

In the emerging society that is digital and information-based, you are not going to be a full citizen, unless you have a certain level of quantitative literacy, which is vastly greater than anything children coming out of our poor communities are developing now. We have to move that bottom quartile up in terms of quantitative literacy, for them to be full participants in the emerging society. It's the same problem attacked in different ways. The other thing that I will say that was important to Bob, is that learning mathematics has a certain kind of cachet, a certain kind of status.

It is supposed to be white people's material or Asian material. It's something that Black and brown people, poor people are not supposed to be good at. When they discover that they are in fact good at it, then that can be an empowering experience. They can then go on to see other potentials in themselves that they didn't expect.

Kai Wright: Charles, I thank you so, so much for this time. Charles Payne is the author of I've Got the Light of Freedom amongst many other works and is a definitive scholar of this era. Thank you so much, Charles.

Charles Payne: Thank you so much for doing this show. Bye-bye.

Kai Wright: United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Jared Paul mixed the podcast version, Kevin Bristow and Milton Ruiz were at the boards for the live show. Our team also includes Carl Boisrond, Emily Botein, Karen Frillmann, Gigi Polizzi, and Christopher Werth. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Veralyn Williams is our executive producer and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @Kai_Wright.

As always, I hope you'll join us for the live version of the show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern streaming at wnyc.org, or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.