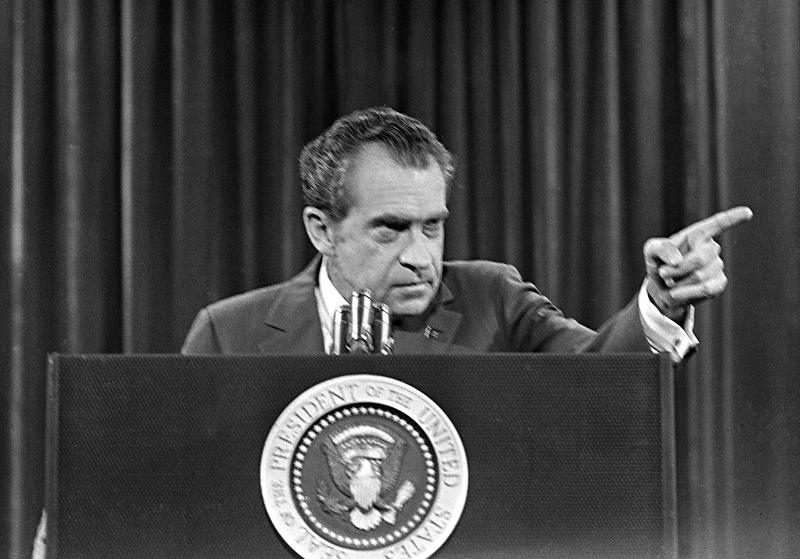

Nixon's Enemies

( AP Photo )

[advertisement]

[music]

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

Kai Wright: We began this season right about the hundred-day mark of the Trump administration. I said in the first episode that we were going to get out of the news cycle so we could think about the broader context. We've done that. Listen, we don't live on Mars. The building questions about the President and abuse of power clearly loom over everything. Of course, that has seriously revived interest in another president.

Elizabeth Holtzman: Here we have the President of the United States firing the head of the FBI because of the investigation that he was conducting. The President of the United States is not above the law.

Brian Lehrer: Now, Trump's recent tweet suggests he's trying to draw a distinction between this situation and Watergate. One of his points is that Comey told him he was not under investigation by Comey at the time he fired Comey. Cox was clearly investigating Nixon. How much does that exonerate Trump in your opinion?

Elizabeth Holtzman: Not at all. President of the United States is not above the law and cannot dictate who is going to be held accountable and in what manner.

Kai Wright: That's former New York Representative Elizabeth Holtzman. She sat on the Congressional committee that investigated Watergate, and she's talking on WNYC's Brian Lehrer Show there. Yes, we too see the Nixon parallels, and they've got us thinking about two specific moments in the Nixon era that feel particularly relevant in today's political culture. I'm Kai Wright. This is the United States of Anxiety: Culture Wars. This is the first of two episodes in which we're going to look back at Richard Milhous Nixon, try to glean some lessons.

[protests]

[music]

Kai Wright: For this story, we're turning to Charlie Herman, an editor in WNYC's newsroom who's been following the investigations into the Trump administration with one eye. With the other eye, he started looking at the Nixon era for us. He says, the first thing you got to remember about Nixon is that he really wanted to make his mark as a global leader. Obviously, the conflict in Vietnam was getting in the way of that. Hey, Charlie.

Charlie Herman: Hey, Kai. Yes, for President Nixon, finding a way to end the war in Vietnam, peace with honor is the phrase that he uses, is this all-consuming affair for him because he is just obsessed with winning, whether it's an election or becoming a great world leader. Remember, this is the man who was a staunch anti-communist. Then he surprises nearly everyone when he announces that he will be the first president to go to Communist China.

Pres. Richard Nixon: This magnificent banquet marks the end of our stay in the people's Republic of China. We have been here a week. This was the week that changed the world.

Charlie Herman: Then, after that trip, he'll be the first president to go to Soviet Moscow.

Pres. Richard Nixon: The memory of your soldiers and ours embracing at the Elbe as allies in 1945 remains strong in millions of hearts in both of our countries. It is my hope that that memory can serve as an inspiration for the renewal of Soviet-American cooperation in the 1970s.

Charlie Herman: To become the global leader that he wants to be, ending the war in Vietnam is crucial. It just frustrates him. He's the person who is resentful of anyone or anything that thwarts him.

Kai Wright: I can imagine from his perspective, at least, he's trying to end the war in a way that allows him and the whole country to claim victory. Yet he looks around and he sees there are millions of Americans marching in the streets protesting against this war.

[protests]

Charlie Herman: These protests just upset Nixon to no end. There's a story about him looking out the windows of the White House and he sees this lone protester standing in the park with this 10-foot sign. Nixon's upset and the word gets around that the sign needs to come down, and one aid volunteers that he'll go get some thugs to get rid of the guy.

Kai Wright: God, does he?

Charlie Herman: No. Luckily, other officials get involved, the Park Service, Secret Service. They convince the protester to move to the back of the park out of sight of the White House. Crisis resolved. This anger at Americans who disagree with him, it fuels this view of the world that you're either with Nixon or you're against him. You can see that clearly in what is now a really famous speech that he gave in his first year as president. He's trying to negotiate a peace deal in Vietnam. He reaches out for the support of what he calls the nation's silent majority.

Pres. Richard Nixon: To you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans, I ask for your support. I pledged in my campaign for the presidency to end the war in a way that we could win the peace.

Charlie Herman: Nixon then goes on to use language that's really personal and emotional to explain what's necessary for that to happen.

Pres. Richard Nixon: Let us be united for peace. Let us also be united against defeat. Because let us understand, North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.

Charlie Herman: Defeat, humiliate. It's almost as if Nixon is blaming the anti-war movement for why the war continues and why he can't bring it to an end. "You're not patriotic. You're dividing us. Your protests are defeating me." Yet, just to give a little bit of context here, this speech is a huge success. There was a Gallup poll that was done afterwards, and it finds that nearly 8 in 10 people of those surveyed support the President's policies in Vietnam. The question remains, how is Nixon going to stop the fighting? How will he bring to a close a war that, when all is said and done, will cost the lives of 58,000 Americans?

Kai Wright: Charlie, neither of us is old enough to really remember this personally, but we are constantly talking about Nixon these days, and it feels like this era, it reveals something about him.

Charlie Herman: Oh, completely. You see all of his ambition, as well as a deep mistrust of people, and eventually even his willingness to use, even abuse, the power of the presidency to hold onto power. It's what leads him to make these really questionable, maybe even amoral decisions, and to engage in illegal acts.

Kai Wright: Like Watergate. Is there more than Watergate?

Charlie Herman: Yes. I don't know where to start. Let's go to 1968. He is a presidential candidate, he's a private citizen, and there is now pretty solid evidence that he interferes in the Vietnam peace talks that the Johnson administration is negotiating. Basically, he gets a message to the South Vietnamese, our allies, telling them that they should wait till after the election, and you'll get a better deal with me, Nixon.

Kai Wright: Hmm. Like getting in touch with the Russians before you take office.

Charlie Herman: I have to tell you, that's exactly what I thought. I was reading about this section, and I remember turning to someone and saying, "Oh, my God, you cannot believe this. Like this back channel communication from a private citizen, what is going on here?" At least when it came to Nixon having these communications with the South Vietnamese, we don't really know what effect it had on the peace talks because the likelihood that there would have been a deal was difficult at best.

It does raise the specter that Nixon's actions contributed to extending the war. Extending the war meant thousands more Americans and Vietnamese died. Now, whether or not this is illegal or even treason, as Lyndon Johnson called it, what it shows is that Nixon is willing to do what it takes to win. If you keep that in mind, then Watergate really isn't that surprising.

Pres. Richard Nixon: I have asked for this radio and television time tonight for the purpose of announcing that we today have concluded an agreement to end the war and bring peace with honor in Vietnam and in Southeast Asia.

Charlie Herman: In fact, it's ironic when Nixon does announce a peace deal in Vietnam, because what should be a crowning moment in his presidency, he has just been reelected in a landslide to his second term in office that just a week later, the jury and the Watergate trial returns guilty verdicts against the last two men who were charged in the break in at the Democratic National Committee's headquarters. That may seem to be the end of the trial and the end of the whole matter. What it really marks is the beginning of a whole new phase. There will be congressional hearings. There will be the revelation that Nixon actually recorded conversations at the White House, and eventually the resignation of Nixon himself.

Kai Wright: Obviously, a lot of stuff came up in those hearings, and a lot of it is disturbingly familiar right now. There is one piece, one particular abuse of power that really caught everybody off guard, and it certainly has an echo today.

President Trump: The enemy of the people. They are. They are the enemy of the people.

Kai Wright: That's next.

[advertisement]

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright. This is the United States of Anxiety. Like a lot of people, we're looking back at the Nixon years. I'm with Charlie Herman, an editor in WNYC's newsroom who's been on the whole Trump investigations beat. Charlie, we were at the moment in your story when the Senate starts its Watergate hearings, and that produced an artifact that got your attention.

Charlie Herman: Exactly. It's called the Enemies List. I got to thinking about that when I heard our current president, President Trump, referring to you and me and pretty much everyone in the media as the enemy of the people.

President Trump: The enemy of the people. They are. They are the enemy of the people.

Charlie Herman: He's using enemy, a word that Richard Nixon used, but in private.

Reporter: The enemy of the people.

Reporter: The enemy of the American people.

Charlie Herman: That language, it reminded me of Nixon.

Pres. Richard Nixon: Press is the enemy. Press is the enemy. The press is the enemy.

Charlie Herman: Kai, if you didn't hear that clearly, the press is the enemy. This is Nixon in 1972 speaking to National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger on one of the secret tapes he made.

Pres. Richard Nixon: Write that in the blackboard 100 times and never forget it.

Kai Wright: Wow. Write that on a blackboard 100 times and never forget it.

Charlie Herman: Nixon sees us, the media, as an enemy. He doesn't really see us as part of the nation's political system. Again, this shows this real dark side that he had, that he is suspicious, that he doesn't trust people, that he's angry. One of his aides later said Nixon felt he was surrounded by enemies. To keep track of them all, Nixon had his staff draw up a proper list of people he considered enemies.

Kai Wright: There was an actual Enemies List?

Charlie Herman: Yes, in fact, there were a couple of lists. It was all part of a White House political enemies project. They were constantly being updated. They kept adding more and more names. There are different counts, but usually you see a total around maybe 200 or 300 names. I found one account that said there were about 700 names. When you look at the list, there are just some really odd names that start appearing, like Carol Channing, or Jane Fonda, Joe Namath, Barbra Streisand.

[MUSIC - Barbra Streisand: People]

Kai Wright: Apparently, Nixon does not hear the message of Barbra song.

Charlie Herman: No, I don't think he did. I have to say, when I look at some of the names on the list, I'm left scratching my head. Many of the names are people who are politicians or members of the media, they're labor or business leaders. People who have some connection to Democrats and progressive movements. Yes, there is a list. The reason that we know about it is because--

John Dean: It was revealed by me during my Senate testimony.

Charlie Herman: John Dean, he was Nixon's White House counsel and later became a star witness before the Senate's Watergate Committee. I called him up at his home in Southern California. Why do you think it made such a big splash and grabbed people's attention?

John Dean: It's just so unpresidential for presidents to have enemies. Theoretically, the President is the President of the United States, not the President of the Republican or Democratic Party, or the President of the people who voted for him. We don't like to think of our leaders as being that narrow-minded that they would-- Everybody is their enemy who isn't their friend.

Charlie Herman: Nixon did see the world that way.

John Dean: Nixon was a man for whom revenge was a very big part of his life. I don't think any slight had ever occurred to him that he'd ever forgotten.

Charlie Herman: On August 16th, 1971, Dean sits down at his typewriter and he bangs out a memo that he says he thought was so obnoxious it would be rejected. Kai, I'm going to give it to you and have you read it.

Kai Wright: Okay, here we go. "Confidential. Subject, 'Dealing with our political enemies.' This memorandum addresses the matter of how we can maximize the fact of our incumbency in dealing with persons known to be active in their opposition to our administration." Stated a bit more bluntly, how can we use the available federal machinery to screw our political enemies? What about the federal machinery part? What's he talking about there?

Charlie Herman: Here is Nixon on one of those White House tapes, trying to figure that out. Let me give you a little hint. The initials are IRS.

Pres. Richard Nixon: Are we looking over the financial contributors? Are we looking over the financial contributors of the Democratic National Committee? Are we running their income tax returns?

Charlie Herman: The tapes can be a bit hard to understand at first, but if you listen closely, Nixon is asking his aides if they have looked at the income tax returns of George McGovern, his opponent in the presidential race, as well as those of contributors to the Democratic Party. In other words, he wants to use the IRS as a weapon to get information on his opponents so he can attack them or at least intimidate them.

Kai Wright: Back to John Dean's memo.

Charlie Herman: Okay, so he writes up this memo, and then he sends it around to other people in the White House. What he gets back is a list of names. Next to about a dozen names, there are blue check marks for those who should be getting top priority. Now, Dean writes this memo in 1971. This list and the other ones, they're circulating around, they're getting updated. More names are getting added to them, and no one outside the administration knows about them.

Reporter: Good morning. At this hour, a select committee of the United States Senate is about to begin public hearings on something called Watergate.

Charlie Herman: Until the whole project comes to light, nearly two years later, when Dean testifies before the Senate Watergate Committee.

John Dean: I began by telling the President that there was a cancer growing on the presidency, and if the cancer was not removed, the President himself would be killed by it.

Charlie Herman: On his second day of testimony, Dean says he slips it in almost as an aside, but it is such an important moment that it even makes the CNN documentary The '70s.

John Dean: There was also maintained what was called an Enemies List, which was rather extensive and continually being updated.

Charlie Herman: The reaction is, what is this? John Dean has just revealed that the White House has kept a list of enemies it wants to screw over.

Rick Perlstein: It really captured the public's imagination, immediately became a public sensation.

Charlie Herman: Rick Perlstein has written about Nixon and the history of the conservative movement.

Rick Perlstein: It really encapsulated to people a certain cultural symbolism about Richard Nixon and what Watergate represented, which was this willingness to go outside the, not merely the laws, but the norms of democratic society to try to stifle people's First Amendment-protected activities.

Charlie Herman: That's for sure. Board reporters, they sit up and take note. TV correspondents go live on air and start talking about the Enemies List, even as they wait to get their own copy of the memo. One of them is Daniel Schorr, who's covering the hearings for CBS News. This is him telling the story to the archive of American television.

Daniel Schorr: I could hear in my ear from my producer back at CBS, "Get names, who, who, what?" Eventually, as we were talking--

Charlie Herman: Someone eventually does hand him the list. Without looking it over, he just starts reading.

Daniel Schorr: There are numbered 20 names numbered. Let's see--

Charlie Herman: He reads each name. He gets to number 15, Stewart Mott, then number 16, Congressman Ron Dellums, then--

Daniel Schorr: 17, Daniel Schorr. Notation, "A real media enemy." Then, I don't know how I looked at it. I've never seen the tape, but I felt as though I was going to gulp and collapse. I did manage to say number 18, Paul Newman, number 19, Mary McGrory, number 20-- Now back to you. Broke into a big sweat. The idea that I was a part of the story that I was covering would be quite incredible.

Kai Wright: Okay, but what are the ramifications here? What happens to him or other people on that list?

Charlie Herman: In the end, probably not a lot, but it wasn't from a lack of trying. This is another part of the Nixon story that feels really relevant to today. We talk a lot about how institutions can protect our democracy, but it also takes individuals who stand by their principles, and that's what happened here. Nixon's Enemies List lands on the desk of the IRS commissioner at the time. He goes to his boss, Treasury Secretary George Shultz, and he asks, "What should I do?" Shultz replies, "Do nothing."

George Shultz: It was an improper use of the IRS, and I wouldn't do it.

Charlie Herman: This is Shultz in an interview for the oral history project at the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

George Shultz: When it came to anything of that kind, where you're using the power of government, I think that you've got to do it properly. I was being asked to do something improper, and I wouldn't do it. I think things like that had been done before. So maybe the President thought he was just doing what others have done. Anyway, not with me.

Charlie Herman: With that, the IRS chief seals up the list of names, locks it in a safe in his office, and no one else at the IRS sees the list. Now, there were news reports and allegations from people saying that they had been harassed by the IRS. That congressional investigation found no evidence that the IRS was more aggressive with people on the Enemies List. Dean admitted as much to Congress when he told them about one meeting with President Nixon.

John Dean: The conversation then turned to the use of the Internal Revenue Service to attack our enemies. I recall telling the President that we had not made much use of this because the White House didn't have the clout to have it done. That the Internal Revenue Service was a rather democratically oriented bureaucracy, and it would be very dangerous to try any such activity. The President seemed somewhat annoyed and said that the Democratic administrations had used this tool well, and after the election, we would get people in these agencies who would be responsive to the White House requirements.

Rick Perlstein: We don't know of anyone who went to jail because of the Enemies List.

Charlie Herman: Again, historian Rick Perlstein.

Rick Perlstein: We don't know anyone who was framed as the result of the Enemies List. I guess we were saved by the fact that he was caught.

Charlie Herman: Yes, he says there's no real indication people suffered, but--

Rick Perlstein: What would have happened with the Enemies List in 1975, say, had Richard Nixon not been caught and resigned in 1974? I think that's anyone's guess, and it's a really frightening prospect.

Charlie Herman: However, over time, being on the Enemies List became something like a badge of honor.

Rick Perlstein: People talked about their disappointment that they weren't on it. People talked about their pride that they were on it. That was their greatest accomplishment. Joke books came out about it.

Charlie Herman: For his part, Daniel Schorr came to see it as one of his biggest honors, and he talked about it frequently. Now it is something we joke about. My favorite actually comes from The Simpsons.

The Simpsons: I got their names written down right here in what I call my Enemies List.

The Simpsons: Jane Fonda, Daniel Schorr, Jack Anderson. Hey, this is Richard Nixon's Enemies List. You just crossed out his name and put yours.

Rick Perlstein: The reason it feels like such a big deal is what it came to represent in the minds of the people. This symbol that you have someone in the most powerful office who is willing to use extralegal and immoral means in order to silence people. Now, the fact is, it turned out to be much harder than he thought.

Charlie Herman: Here's where I want to introduce someone whose story is a cautionary tale about why this matters, how this mindset of a White House having personal enemies is so destructive.

Morton Halperin: My name is Morton Halperin, and I'm now a senior advisor to the Open Society Foundations.

Charlie Herman: Halperin has had a long career in government and at nonprofits and think tanks like the ACLU and the Brookings Institution. He was also enemy number eight on Nixon's list. What was your reaction when you heard that your name was on this list?

Morton Halperin: I was astonished. Didn't have any idea they were. It turns out, I think it said next to my name that I was at Common Cause. It also said next to my name, a scandal would be helpful here. Somebody thought that I was somebody they should worry about. It's never been clear to me exactly what triggered it or why.

Charlie Herman: In fact, this wasn't Halperin's first run-in with the Nixon White House. Years earlier, before the Enemies List was drawn up, he worked for Nixon as a staff member to Henry Kissinger.

Morton Halperin: I was the senior director dealing with policy planning and the National Security Council and with arms control issues.

Charlie Herman: He knows what it's like to be the target of an administration that decides it's going to use the power of the federal government to go after an American citizen it deems a potential threat. Without a court order or a warrant from a judge, the FBI wiretapped Halperin even when he was still working for Kissinger, believing that he might be leaking information to the media about the Vietnam War. How did you react when you learned that?

Morton Halperin: I was angry and upset and decided pretty quickly that I would sue the people who did it, starting with Kissinger. I did that.

Charlie Herman: Even though the wiretap provided nothing of value and the FBI suggested ending it, Kissinger kept it going. It lasted for nearly two years, and Halperin only learned about it years later.

Morton Halperin: It felt like a violation of my privacy and that of my family. It was much more intimate and personal than the surveillance that goes on now. This was a law student working his way through law school, sitting in the evening in what is now the Trump Hotel, just to show that everything comes around, which was then the top floor was the field headquarters of the FBI in Washington. He sat there every evening for 21 months listening to the phone calls of me and my family.

Charlie Herman: Halperin did sue Kissinger. After nearly 20 years, the two sides finally settled when Kissinger agreed to write a letter of apology and accept moral responsibility.

Morton Halperin: The notion that somehow the President thinks of himself as having enemies is, I think, wholly inappropriate, very dangerous, and very scary.

Kai Wright: Institutions mattered in reining in Nixon's abuse of power. As Halperin and all the players in Charlie's story remind us, so did individuals. The whole thing was pretty intimate and personal. That was true for people targeted, but also for people who pushed back, like Treasury Secretary George Shultz, who refused to act on Nixon's Enemies List. That got us thinking about now, of course. Not just in the whole Trump saga, but in all of our own lives. Standing up to powerful people when they tell you to do something wrong is hard, and it often has consequences.

We're curious if any of you have experience doing it either on your job or elsewhere. If so, call us up and leave a voicemail telling the story. 844-745-TALK. That's 844-745-8255. Meanwhile, we're going to keep thinking about Nixon, but not about Watergate. There's another part of his legacy that is very relevant right now.

Pres. Richard Nixon: America's public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse.

Kai Wright: That's next time. United States of Anxiety: Culture Wars is a production of the narrative unit of WNYC News and WNYC Studios. Charlie Herman reported this episode. The narrative unit team also includes Reniqua Allen, Rebecca Carroll, and Patricia Willens. Casey Means is our technical director with help from Bill Moss and Wayne Schulmeister. Hannis Brown is our composer, and our theme was performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band.

Andy Lancett is our archivist. Our digital team is Lee Hill, Diane Jeanty, and Jennifer Hsu. Jim Schachter is vice president of news for WNYC. Jessica Miller is our producer. Karen Fillman is our editor and executive producer. I am Kai Wright. Talk to you next time.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.