Desegregation By Any Means Necessary

( Marianne McCune )

Kai Wright: Hey everybody, just a heads up before you listen to this episode, there's a good bit of salty language in it. If you're not in the mood for that, or if you're listening with somebody you don't want to expose to that, then try this one later. Thanks. Otherwise, enjoy.

[music]

Kai: This is The United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history, and its grip on our future.

Hari Sreenivasan: Brown versus Board of Education declared school-based racial segregation to be unconstitutional. It was intended to desegregate schools, but that isn't exactly what happened.

Nikole Hannah-Jones: There's not an easy answer. I think we always want it to be easy but undoing racial caste in an educational system is not easy.

Gov. George Wallace: And I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.

Edna Allen-Bledsoe: I never really realized how unequal things were until I came back here.

Lurie Daniel Favors: We're talking about physical placement. We're not talking about a culturally competent education.

Speaker 6: Students are not resting, we are not going to rest, because this is not okay. It's not fair, and a public school system should not be propagating inequities between communities.

[music]

Kai: Welcome to the show, I'm Kai Wright. Schools, it is hard to find a more plain example of unfinished business in our history than the very long debate over how to equitably educate our kids. From pre-k all the way up to graduate programs, it's been a core challenge since at least reconstruction, culturally, politically, and legally. Yet, we are constantly reminded how little progress has actually been made. Schools remain starkly segregated by both race and class. Even among seemingly integrated school systems, it often turns out there's stark segregation within each school, as the pandemic has dramatically reminded us.

In today's show, we turn to a story we began telling just before the pandemic erupted. A story about one little tiny school district in California, where a school superintendent is trying to solve this very old problem, again, actually. His name is Itoco Garcia. He has actually been ordered to desegregate his district in a really unusual suit brought by California's attorney general, though Itoco says that doesn't actually make him or his district that special.

Itoco Garcia: This case could have happened across the land in public school districts. I could throw a rock and hit several other places from here, where this is an issue. This one was just obvious, and it's small, and it's in a community where no one would ever believe it could or should happen.

Kai: Itoco's district is in Marin County just north of San Francisco. Do stay with us if you heard our story last year about this ongoing struggle with desegregation, because this is not a repeat. Today, we are bringing you the sequel and the prequel, because what's remarkable in this story is that just like New York, Itoco's district already desegregated its schools more than 50 years ago. In fact, this community was among the first in the country to voluntarily desegregate. Their approach back then was unapologetically bold, we're talking Black Panther breakfast and a principal with a gun. This week, I'm going to hand you over to our reporter, Marianne McCune, who's going to take us back to that time. First, she catches us up on where we left off in the story.

Marianne McCune: Okay, so first of all, I want you to know a couple of things about Itoco Garcia, this man who is tasked with orchestrating a lasting change for the kids in this school district. Itoco is not an outsider to this place, and when I say this place, I'm really talking about two places. Two very different communities that are part of the same small school district. One is a wealthy white town called Sausalito that climbs up the slope of a hill overlooking the bank. It was in those hills, even further up, that Itoco grew up with his white mom in white elementary schools, but Itoco's father was from an Indigenous group in Colombia. He was a doctor and an intellectual, and he made sure that Itoco also spoke Spanish and learned his Latin American history.

Itoco: Who Emiliano Zapata was, who Pancho Villa was, what they did, why they did it, this was really important to him. We were doing a read-aloud in class, and we happened to be reading the part about Latin American liberation. I didn't know how to anglicize those names, so I read them that way; Emiliano Zapata, Simon Bolivar, and my whole class fell out laughing. My teacher said, "Read it again," and so I started reading again, and she said, "Stop. Read it again." I couldn't, and she kicked me out of class and sent me to the principal's office for being defiant and disruptive.

Marianne: It wasn't until Itoco was in middle school that he discovered Marin City, which is the other half of this school district. Marin City is not a city, it's an unincorporated part of the county. It's the only place where thousands of Black shipbuilders who came to work here during World War 2 were allowed to make their homes after the war ended, and it's where Itoco played sports growing up.

Itoco: I remember distinctly it being the first place that I really felt welcomed.

Marianne: It was not a white space, and by high school in the early '90s, Itoco had made a decision, he was not white.

Itoco: I am not going to do anything to try to be white. As a matter of fact, I'm going to show culturally and linguistically as much as I can opposite of white.

Marianne: He went on to UC Berkeley, got a doctorate in education, and decades later when Itoco came back to this community to become superintendent of the school district here--

Itoco: I knew exactly what I was getting into.

Xavier Becerra: I want to thank everyone for being with us here this morning--

Marianne: This is State Attorney General Xavier Becerra, summer of 2019. He's now a member of the Biden administration. He made his big announcement in a Marin City playground, and this was historic, the first desegregation order in California in 50 years.

Xavier Becerra: Brown v. Board of Education ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, but more importantly, they said, separate is not equal.

Marianne: The big picture of what the AG laid out was this, there were just two public schools in this community. Both were K through eight. One was a regular public school, 120 or so kids, almost all of them Black or brown and low income. That school was in Marin City. The other was over on the hill in Sausalito, a charter school about four times bigger and quite diverse, but it had almost every single white student in the district. The attorney general investigated and determined that for years, the people leading this little district with just the two schools had neglected the regular public school and its almost exclusively Black and brown students, while helping the diverse charter school where all the white students were, flourish and grow.

Xavier Becerra: The Sausalito Marin City School District schools were separate, and they were not equal.

Marianne: It was Itoco's job to fix it.

[music]

His task was to make a school that would attract Black families from local public housing, and immigrant families who spoke Spanish, or Tagalog, or Arabic, and white families too from the funky little boathouses on the bay to the luxury houses on the hill. Itoco's strategy, to bring the two existing schools together into one. Find a way to combine the charter school with the regular district school, and the problem was distrust, a decade's deep distrust.

Speaker 7: --I don't doubt that many of you relish harming the institution, but what I cannot fathom is how can you continue to push an agenda that actively harms the well-being of 180 students?

Marianne: Itoco's first few months on the job involved many long nights, sitting at one end of a school cafeteria, listening to charter school parents damn the district-

Speaker 8: Why is Willow Creek Academy being penalized?

Marianne: -and too, supporters of the regular public school damn and the charter.

Speaker 9: Because you guys brag about diversity. You have flyers out there with Black faces on, all this promoting diversity. "We're diverse. We love our diversity," but Black children aren't being taught at your school.

Marianne: As Itoco listened, one of the things he worried most about was how not to fall into the patterns of the past. This fight over segregation, and integration, and resources, and inequity, it's been going on for decades. You can find local newspaper clippings detailing the same debates over and over from World War 2 on. Back in 1970, a BBC documentary told the story of a sweeping effort to fix things.

BBC Reporter: Five years ago, a locally elected school board in Sausalito, California, with foresight and idealism, created one of the first deliberately integrated school systems in the United States.

Marianne: It was a portrait of this same little district's first effort to desegregate.

Speaker 9: It's a racist Sausalito School District.

BBC Reporter: What do any of the rest of you think about it?

Marianne: When Itoco found and watched the BBC coverage, he says it actually made him cry.

Itoco: I had a brief moment when I thought, "Oh, boy."

Marianne: Why?

Itoco: Because it seemed like we were in the same place in 2019 that this community was in in 1965. There were accusations against school board members, and actions against school boards, and recalls, and angry parent meetings. Angry Black parents talking about racism and segregation, angry white parents talking about behavior and learning. I mean, there are things that have not changed much at all.

[music]

Marianne: Maybe the biggest stickiest pattern the documentary points to is this, that desegregation alone does not equal success for Black students. The whole idea of school desegregation was to improve education for Black kids who had been forced to attend overcrowded and underfunded schools, but desegregation, just putting Black and white students together, was that enough?

Royce McLemore: We're going to keep on pushing until--

Marianne: In the BBC documentary, a Black Marin City resident named Royce McLemore, with a gorgeous crochet sweater vest and a 1970 Afro tells the interviewer--

Royce McLemore: Me, myself, I don't care about integration. All I care is equal education.

BBC Reporter: What you're saying basically is--

Marianne: Royce still lives in Marin City. She's been an activist, and an educator, and a foster mom out of the local public housing complex for decades. Everyone here knows her. At 77, she still questions desegregation. She's told Itoco, "So what if the public school in Marin City has almost all Black and brown kids? Why do we have to cater to white families now?"

Royce McLemore: If they're going to leave, let them leave. They left back in the day. I said that on the BBC, I still feel the same. I don't care about integration. It's about the best education that one can receive, equal education.

Marianne: Itoco has thought about this plenty. On one hand, research shows desegregating schools has done more to improve educational outcomes for Black students than any other reform. On the other hand, it hasn't done nearly enough. Itoco doesn't really have a choice in the matter. The attorney general has ordered desegregation, so he can't just focus on educating the Black and brown students who already attend his school. To desegregate, the district has to attract some white families too. Does trying to please wealthy white families force compromises that are not in line with serving the families that you're talking about?

Itoco: Historically, yes.

Marianne: Is that in your mind? Do you feel you have to find ways to resist that historic trend?

Itoco: I think that feeling enthuses my entire educational journey as a student, as a teacher, as a principal, and as a superintendent.

Marianne: Itoco pledges not to fail Black families in order to serve white ones.

Itoco: That is our charge in this community, and I believe that we are very well positioned to do just that.

Marianne: Which is exactly what the superintendent of this district was hoping 50 years ago before things fell apart.

[music]

Kai: Coming up, we'll hear what went wrong and what went right. I'm Kai Wright, and this is the United States of Anxiety. We'll be right back.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. This is the United States of Anxiety, I'm Kai Wright. This week, our reporter Marianne McCune is telling us the story of a school desegregation effort in Marin County in California. It's a project that, not surprisingly, has been tried there before more than 50 years ago. Marianne is taking us back in time.

[music]

Marianne: I went to visit a woman who lives way up on the hill in Sausalito, great 1960s modern house, the same house that she was sitting in 50 years ago when she and her husband were also interviewed by that BBC reporter.

BBC Reporter: What experiences have you had that have made you come to the realizations that you have come to?

Jackie Kudler: Well, the prevalent or the prevailing--

Marianne: They talked for a while, and when the interview was over, Jackie Kudler remembers telling the reporter--

Jackie Kudler: Be kind. I know we're going to come out to be these naive bleeding heart liberals, and we were.

Marianne: When they moved to Sausalito in 1962, Jackie was a teacher from Brooklyn, her husband was a dentist.

Jackie Kudler: John Kennedy was president--

Marianne: They had a baby, they're a Jewish family--

Jackie Kudler: I think two weeks after we came to Sausalito, I got a call asking if we liked to come for coffee, and we began to meet a whole bunch of people talking about, "You know, we have a segregated school district here." The Black kids went to school in Marin City, and the white kids went to school in Sausalito. It was like, you know what? This is wrong.

Marianne: The crowd you're talking about, were they mostly white families from Sausalito or--?

Jackie Kudler: All white. I mean, we were Sausalito people at that point, and it's just that it was wrong, and we were going to make it right.

Marianne: Jackie and her group of like-minded parents ran for seats on the school board and managed to get a majority. Their campaign was all about the need for desegregation.

Jackie Kudler: They kept saying, "All we have to do is get Black and white kids together, and it's going to be fine." There was a kind of naivete about how easy it would be.

Marianne: But they went ahead. It was 1965, and this was one of the first voluntary desegregation efforts in the country. They hired a new reform-minded superintendent, someone with the same ambition Itoco Garcia has now. They hired school buses, and in each school in the district, there were a few back then. They mixed up the Black and white students, but it was pretty immediately clear that just putting kids together wasn't enough. Around that time, Royce McLemore was a very young mom sending her oldest daughter to elementary school.

Royce McLemore: I decided to go see what was going on at her school-

Marianne: Royce is the Black Marin City woman who said back then, and again more recently, that integration alone does not add up to equal education for Black students.

Royce McLemore: -and it was like Blackboard Jungle in the classroom. You had kids literally on top of the desk, they were doing whatever they wanted to do. Then you had the teacher, Mr. Kincaid was his name, just saying, "Class, class," and they just ignored him. I was shocked.

Marianne: Royce and Jackie got to know each other early on in this desegregation project. They were both mothers in the district, and they talked about the problems they were seeing.

Jackie Kudler: There were white teachers there that we were trying to get rid of who the Black community said were terrible. They suffered through those teachers who just didn't have a clue.

Marianne: By terrible, do you mean bad teachers, or they treated the Black children badly?

Jackie Kudler: They treated the Black children badly, and what they had to teach, ignored the Black children. Fine for my kid, my kid was just as happy as could be.

Royce McLemore: I decided to go to one of their board meetings and saw these white people up there, and there they are talking about what's best. That just did something to me. I told them, "You can't tell me what's best for me and mine."

Marianne: This was just the very beginning of a journey for Royce McLemore, her first school board meeting, a turning point.

Royce McLemore: Growing up, I didn't know anything about my history. Then when I was in high school, in social studies, they had us in the trees with a bone through the nose, and condescending, and make you feel, "Ugh," you know--

Marianne: But things were shifting. In 1966, Royce attended a speech in Berkeley that she says moved her.

Royce McLemore: I saw Stokely Carmichael-

Marianne: The Black leader of SNCC, the student-run civil rights group.

Royce McLemore: -he was speaking at Cal.

Stokely Carmichael: We are on the move for our liberation. We are tired of trying to explain to white people that we're not going to hurt them. We are concerned with getting the things we want--

Royce McLemore: It just really lit something up inside of me to really be proud to be who I am.

Stokely Carmichael: If that does not happen, brothers and sisters, we have no choice but to say very clearly, move over or we're going to move on over you.

Marianne: In Sausalito, that white progressive superintendent and Jackie Kudler's group of liberal parents, they were trying to listen to the Black Power Movement and do desegregation better.

Jackie Kudler: We understood that it was important to hire Black teachers, and that's what we did.

Marianne: The superintendent brought in Black student teachers and some staff, and he also orchestrated what were called encounter groups at the time, to raise consciousness about the Black experience. Here's something that might sound familiar to Black listeners, there were so few Black staff that each of them had to go to multiple encounter groups a week to represent. At the middle school, the Black Panthers started their signature breakfast program, Panthers in black berets serving up eggs and bacon to the kids in the cafeteria.

One teacher told me that she remembers this little old white lady the school hired to cook. When the Panthers saw her frying up breakfast in butter instead of bacon grease, she says they jumped in the kitchen with her to make things right.

Royce McLemore: When the Black Panther Movement began, that just stirred me up even more.

Jackie Kudler: But the Panthers were gun-toting people, and for a lot of white people, it was like, "They're scary people."

Marianne: The superintendent's next move was arguably his boldest and most controversial. Before we get there, let me just remind you of what these final few years of the 1960s were like.

News Reporter: Direct from our newsroom in Washington--

Marianne: Black unemployment was rising, as were tensions over police abuse.

News Reporter: Good evening, Dr. Martin Luther King-

Marianne: Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968--

News Reporter: -has been shot to death in Memphis, Tennessee.

Marianne: There were continued protests over Vietnam, over civil rights. In San Francisco, Black students and their allies boycotted classes for a full five months demanding more Black professors and a Black studies department. That was the context in which in 1969, a white progressive superintendent hired as principal of the middle school, a Black educator from Oakland named Sid Walton. Brother Sid, he liked students to call him. Sid had some very different ideas about what middle school kids should learn.

Sid Walton: At some time or another, children have to be exposed to the hypocrisy in the society-

Marianne: Here he is in that BBC documentary.

Sid Walton: -and you know, we can't get into this garbage about, George Washington was the father of our country. George Washington was a damn slave owner. There are a lot of whites who would not want it known that George Washington was a slave owner. Those are the kinds of things that we're talking about. We're teaching the truth.

[music]

Sid Walton: All ready.

Speaker 10: Testing--

Marianne: It's worth taking a moment to get to know Sid Walton. It took a while to find him all these years later, and when I did, he was always so busy for an 86-year-old. Doing something with his boat, or with his car, but eventually, he made time for me.

Sid Walton: Do you want me to leave this on?

Speaker 10: Yes.

Marianne: To keep him safe from the pandemic, I parked in his driveway, just south of San Francisco, strung a disinfected microphone into his car-

Sid Walton: Like so?

Speaker 10: Yes, but as much as possible--

Marianne: -and we talked for hours on the phone.

Sid Walton: All right, so I'll roll this up then.

Marianne: We could see each other through our rolled-up windows.

Sid Walton: There's a nice restroom, a woman-friendly restroom at Walgreens.

Marianne: I'll just try to hold it in, but if I need [crosstalk]--

Sid Walton: No, no, no, we don't want any squirming. [chuckles]

Marianne: Sid Walton's year as principal in Sausalito, Marin City, looms large in the history of that seaside town, but it was just one year of his life. To understand what his project was in that middle school, it helps to go back to where he started. What's the story of you becoming an activist? Tell me that story.

Sid Walton: I was born Black, and they were fucking with Black people. We had to let them know--

Marianne: Sid's whole life story is about not backing down, which seems like it must have been true for his mom too.

Sid Walton: When I was three years old, she took me flying in a Piper J-3 Cub.

Marianne: This is a Black woman in Illinois in 1937-

Sid Walton: 1937.

Marianne: -and she got her pilot's license and took her little boy for a ride.

Sid Walton: We got way up, and she got real high, and then we came back down and things started getting bigger. My mother flew a plane at a time when women-- A lot of women couldn't drive a damn car, and she's up there flying a damn plane-- [sobs] I don't know-- I've had a unique life.

Marianne: Sid it has a story about what turned him into a teacher. He comes from a family of firefighters. He was a fire chief in the army for a couple of years, and when he came back, he took the test to become a firefighter in a suburb of California.

Sid Walton: Do you know what those bastards told me? They said that I could not live in the station with the other firefighters because they weren't integrated. I said, "You motherfuckers. You know what I'm going to do? You take this job, and you stick it up your ass." I said, "What I'm going to do is, I'm going to go back to school, I'm going to get my credentials, and every kid I come in contact with, I am going to tell them how racist you motherfuckers were." That's my little story about why I became a teacher.

Marianne: Sid was the first Black teacher in one Bay area School District, then he was the first Black counselor at a junior college in Oakland. He says the guys who told him about that job were none other than the founders of the Black Panther Party. His friends, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale.

Speaker 11: The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense calls upon the American people in general, and the Black people in particular, to take careful note of the racist California legislature.

Marianne: This was around the time the Panthers traveled to the California State Capitol building to make a point about their right to bear arms, and Sid was there too. He says he wasn't a member, just an ally.

Speaker 11: --Racist police agencies throughout the country by intensifying the terror, brutality, murder, and the oppression of Black people.

Sid Walton: I joined with them, we carried our guns up to Sacramento, and we stood down the police that were supposed to be protecting the state Capitol.

Speaker 11: Am I under arrest? Am I under arrest?

Sid Walton: We kept our guns, and they're alive, and we're alive.

Speaker 11: The California Penal Code Section 12020 through 12027, and also the Second Amendment of the constitution guarantees the citizens a right to bear arms on public property.

Sid Walton: Basically, that is my message to racists, is that, if you are willing to die to do what you want to do, then I'm willing to die to stop you from doing it.

[car horn]

Marianne: Oops, nice punctuation there. [laughs] Sid's main focus was on the power of words, not guns. He pushed the idea of Black Power in a space it hadn't been before, education. Sid was instrumental in starting the first Black studies department on an American campus. He chronicled the effort in an unusual book called The Black Curriculum. I say unusual because it's not just a narrative, it's more like documentation. He includes the transcript of a counseling session in which a student talks about racism in a classroom, and he encourages her to speak up. He reprints his speech to administrators in defense of the word 'mother', et cetera, in a play by Amiri Baraka he brought to the college.

Sid Walton: Yes, we were going to be using the fucking magic word, and that was it.

Marianne: He told them, "Hey, this is how enslaved people describe the white men who raped their mothers." Sid also included in the book a whole series of these bureaucratic letters back and forth with administrators telling him he doesn't have the right to do what he's planning, he has to jump through this and that hoop, he's got to go through such and such a channel. Tell me about tricknology.

Sid Walton: Tricknology? Oh, tricknology-- [laughs] I forgot. Tricknology was some of the things that white folks would do to Black folks, in terms of shifting shit around.

Marianne: Like, "We'll do that, but it's going to take a long time."

Sid Walton: Exactly, that kind of shit. They always would come up with some provisos that they'd put in.

Marianne: Like things that would prevent a Black person from getting a job, or getting a promotion, or that kind of thing?

Sid Walton: Yes, and we just referred to it as tricknology.

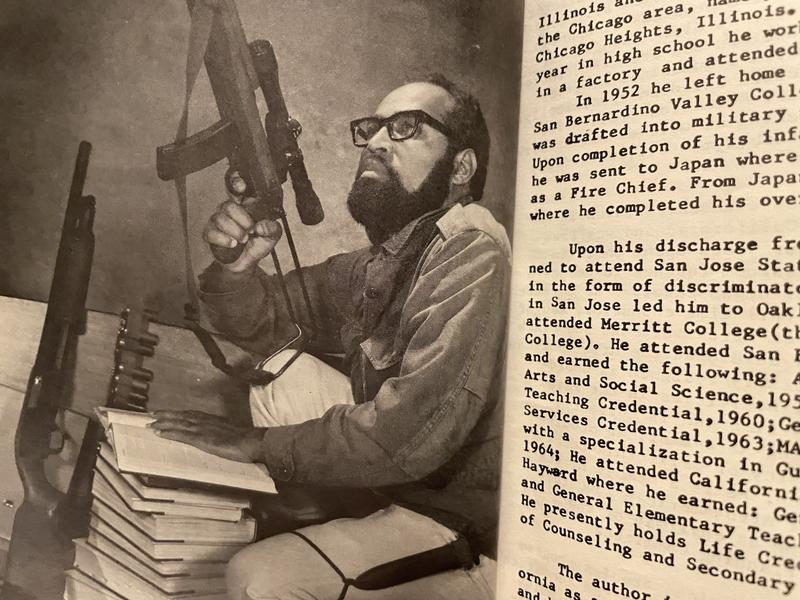

Marianne: Sid's book, The Black Curriculum, is like a manual for how to get around tricknology. Sid was known among Black educators and radical students, but it's not like The Black Curriculum was selling out in bookstores the way anti-racism books have this past year. Sid self-published, which explains why when he was hired as principal across the Bay in Sausalito, most parents had never seen it, until The San Francisco Examiner reprinted the only photograph in the book. There was Sid, their newly hired middle school principal, bearded, Black glasses, kneeling next to a foot-high stack of books, holding a rifle. There's a round of ammo, and another gun leaning against the books, and a knife strapped to Sid's thigh.

Sid Walton: Because we need books, and knowledge, and the guns to get our freedom. We're book-based, but we're also gun-backed-up.

Marianne: In Royce McLemore's memory, when Brother Sid took over as principal, he turned things around in a way she had never seen before.

Royce McLemore: For generations, the Sausalito School District had miseducated Black children. There were very few that would graduate from the eighth grade that would be able to actually be on the same level with the white students from other parts of the county. When Sid Walton had become the principal, what I saw that was different is everybody started feeling good about being Black. I mean, that was it.

Marianne: What were they doing differently in the school that instilled that?

Royce McLemore: Well, that they had an opportunity to speak how they feel, any injustice that they saw, that they were able to address it. Not disrespectfully, but as young Black people, to be able to express how they felt about various situations, and so he opened that door up for them to be able to do that. The teachers had to do a lot of in-service training, and they had to do some reading in terms of what contributions Black people made in history. Even white teachers that were there, they were getting pumped too in terms of, yes, people have been done wrong, and this was an opportunity to make it right through that next generation of children. He was helping us, guiding us as parents, what to advocate for your children, and we did.

Marianne: Like what would he say?

Royce McLemore: That you have a right, and don't let them take that right away from you. He was able to ignite that feeling that you are proud to be Black when you get exposed to someone that's really fiery, and highly motivated, and intelligent. Gone are the days of shuffling and bowing. [laughs] That was over. We weren't having that. [laughs]

Marianne: That's the way Royce remembers it, but there were a whole other set of stories about Sid and how he ran the middle school that year. The kind of stuff that people who did not want things to change this much wrote in letters to the editor and official reports. They saw it as the radicalization of the middle school. Jackie Kudler was still supporting the district's decisions and Sid, but she was encountering more and more detractors.

Jackie Kudler: There was a political element that came into the curriculum that became very jarring for a lot of white people.

Marianne: Kids were pulled out of math to learn Swahili, the student council voted to fly the flag at half-mast until the end of the Vietnam War, and Sid ended up in a battle with local firefighters who would regularly drive up and raise it. The new books appearing in the library were Eldridge Cleaver's Soul on Ice, and Mao's Little Red Book. Posters on the walls said, "Free Huey Newton."

Jackie Kudler: The whole thing sounded less like a school than like some political movement, which it was.

Marianne: One teacher from that time remembers Sid loading up his sailboat with supplies for the Native Americans who occupied Alcatraz that year, and then he'd sail across the bay with a student to deliver the goods. That teacher described Sid as a nutcase, but she said the principal before him was brain-dead. By spring semester, everyone was feeling threatened. Royce joined a group called The Black Liberation Army, and was doing target practice in the hills. Jackie Kudler and her husband were starting to feel afraid of the Black militants with intimidating dogs showing up at school board meetings, but also of all the angry white parents

Jackie Kudler: I got a postcard, "You don't keep your big mouth shut, your husband is going to lose lots of patients." Or, "How would you like if your kid married one of those Black bastards?" because I was defending the school-- Oh, and I'm Jewish, it ended with, "Hitler had the right idea." [laughs]

Marianne: Sid said he was also getting periodic death threats.

Sid Walton: I was in the office working late, and phone ring, and it said, "You're in our crosshairs." White folks are always afraid of an outspoken man of color. What can I say? That's the reason why so many of us are killed. I'm surprised that I'm alive to this day. I'm really surprised, but I guess I'm just lucky.

Marianne: It wasn't gunshots that defeated Sid Walton 50-plus years ago with the end of his first year as a middle school principal approaching, it was backlash. In May, at a chaotic meeting before an angry crowd of parents, white and Black, the school board voted to fire Sid Walton.

Royce McLemore: Instead of going forward-thinking, the school district wanted to go back, and went back in there thinking.

Marianne: Royce McLemore watched as the school board also got rid of the Black student teachers, fired another Black teacher for being insubordinate and hired a new principal, also Black, but with the same traditional approach to education the school had to begin with.

Royce McLemore: Been there and done that, I saw what it was, and not interested in going backwards.

Marianne: What was backwards about it? What was wrong?

Royce McLemore: Backwards, going back to, 'if you're white, you're right'.

Speaker 12: I've been trying to work within the system or whatever it is for quite some time--

Marianne: Towards the end of that BBC documentary, you see all those Black parents who had been so inspired by Sid Walton voicing their outrage.

Speaker 12: How can we continue?

Speaker 13: You're dismissing the man without any charges. You know goddamn well you mean to let him go, don't you? Just like you did Sid Walton.

Marianne: Jackie Kudler says her big epiphany came after that year was over when she got together with both Black and white activists to talk about creating a new school. They sat together and tried to imagine what it would look like, and as they talked, she realized--

Jackie Kudler: I think we want different things. I remember going to meetings where some Black guys were talking about, "We need relevant education for our kids. It needs to be relevant." I mean, what's relevant to all of us? How do we build a curriculum that's going to work for all of these kids?

Marianne: Neither Jackie nor Royce kept their kids in the public schools. In fact, they each helped start new schools. At Royce's school, there were murals of Black radicals. One of them, a bloody portrait of an activist who'd been shot dead while taking a hostage at the Marin County courthouse. Jackie's was more of a hippie school.

Jackie Kudler: I tell, you what I felt was, I never want to tell anybody else what they should do with their kids again. I'm going to focus my energy on what I want for my own kid, because I'm off-base. We're all off-base.

Marianne: Royce McLemore still runs a tiny school today right out of a public housing apartment. Toward the end of our conversation, a little boy knocked on the door of her office.

Royce McLemore: Open.

Student: I was gonna say, when do we get our spring break from going to school?

Royce McLemore: Oh, you just got back today. You should've been here yesterday. [chuckles]

Marianne: What do you hold onto from those days when you were seeing Sid Walton at this school? What are the lessons that you learned from that era?

Royce McLemore: To know who you are, to instill in you who you are as a Black person.

Kai: Up next, we'll return to the desegregation effort underway now in Marin County. This is The United States of Anxiety, I'm Kai Wright. We'll be right back.

[music]

Kai: Hey, this is Kai. Just a quick program note here, when we started making this show back in 2016, we were just trying to bring context to that wild campaign season, and particularly, the history that we all carried into it. Initially, we figured we'd stop after that election, but obviously, there was a lot more to chew on. Which is just to say, if you're new to the show, there are tons of episodes here that I hope you'll check out. We've taken snapshots of the political culture.

Speaker 15: It's not right. I'm sorry. I feel bad for people that are oppressed, and I mean oppressed, but we got to take care of our own too.

Kai: We've asked how power is really built in a democracy.

Speaker 16: I don't believe that democracy is destiny. I think democracy is a pathway, but it takes work, and we are the first campaign in the Deep South to put in the work.

Kai: And we've just mined all kinds of history in an effort to put America on the couch, to understand how we got here as a country and where we're going. I urge you to dig around in the archives, it is all still relevant. If you hear something that raises new questions for you and you want us to follow up on that, hit me up. Email me at anxiety@wnyc.org, and maybe we'll take you up on it. Thanks a bunch.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. This is The United States of Anxiety, I'm Kai Wright. This week, our reporter Marianne McCune is telling the story of one little school district in Marin County, California, and its 50-year effort to truly desegregate.

Marianne: The first time I visited the Sausalito Marin City School District was exactly 50 years after Sid Walton was there. One of the conversations I had that day really surprised me. It was with the school librarians, and they told me they had just overhauled their selection of books.

Librarian 1: The big change was the kids needed to see themselves in the books. If you don't see yourself, you're like, "Well, all I see on books are white kids that become doctors, or white kids that can build robots."

Marianne: I was so surprised that a full 50 years after Sid Walton put a copy of Eldridge Cleaver's Soul on Ice in the library, at the same school, these librarians were still working on stocking books about people who look like their students.

Librarian 1: There's some stuff on, say like, Cesar Chavez, or there's Black Panther. We even have board books with Black Panther.

Marianne: Can you think of a kid who would come in here before there were a lot of books with brown and Black faces on them who would be like, "Uh, not that into it," and who now has been like, "Oh, Trevor Noah," or--

Librarian 1: Well, the change that we've seen is not just one kid, it would be groups of kids. They now come in on their recess time to check out books.

Marianne: You really see that big of a difference?

Librarian 1: We do.

Librarian 2: Oh, yes.

Librarian 1: From two years ago, we see over half of the school now, "Oh, you have this book? Oh, you have that book?" I'm just like, "Yes." [chuckles]

Marianne: You have to wonder, what would the shelves of this library be lined with now if Sid Walton had been allowed to stay? That is the kind of question that bounces around in the back of Itoco Garcia's mind all the time, now that he's leading this district's second go at desegregation 50 years later, because their aim back then was the same as his now, to do more than desegregate. They wanted to make the schools a place where Black students were as successful as white ones.

Itoco: I got back and I study it a lot.

Marianne: And what do you see? Tell me what that story of Sid Walton's year in this district means to you now.

Itoco: I think we all got to be Sid Walton for this to work. He did something incredibly courageous. Very few people would have had the courage to come and do what he did here.

Marianne: Like what?

Itoco: We all have to lean into the idea that Black and brown people are excellent, and are as smart, and have as valuable contributions as white folks, and that Black and brown culture is excellent and has as valuable contributions as white culture. To even show up with the educational philosophy and the curriculum that he was espousing, it was groundbreaking. It's taken educational research 45, 50 years to catch up to what Sidney Walton was talking about. That's really what I mean when I say we all have to be Sid Walton.

Marianne: Do you think Marin City, Sausalito is ready for a Sid Walton or many Sid Waltons?

Itoco: Well, I was just going to say, beware of extremists on either side. Maybe that's where Sid Walton didn't get it right. I don't think he was too radical for Marin City. He was obviously too radical for Sausalito. I think we all have to carry his spirit, but the mistake that was made by this community was believing that one man could hold that charge. I know I am one frail human being, this is not work that can be accomplished by one person. This has to be a movement, it has to be a movement.

[music]

Marianne: Before we get to the movement, I need to do one last bit of explaining. That year that Sid Walton was fired and everything seemed to blow up in the Sausalito School District, the integration of those schools, that did not completely blow up. At first, there was white flight. From 1965 to 1970, the year Sid was fired, more than half of the white families left. Local real estate agents started telling wealthy white home buyers, "There are no public schools in Sausalito." There was one group of white students who didn't really have the option to leave, army brats. There were a few nearby military bases, and their kids stayed all the way through the '70s. A lot of people remember those integrated schools as not bad. Even Royce McLemore relented and sent her three youngest children to the middle school.

Royce McLemore: It was small and had some good, strong Black teachers. Small classrooms, and teachers that weren't taking any mess. It was like day and night from when it was Blackboard Jungle.

Marianne: Royce's friend, Jackie Kudler, was drawn back there too. The little overwhelmingly white private school where she was teaching was invited to become an alternative public school. They would just have to give half their seats to Black students, which Jackie says was perfect, as long as the school's white families could keep the curriculum they wanted.

Jackie Kudler: We were trying to introduce a more progressive kind of education that encouraged creativity and blah, blah, blah. What we didn't do was close the achievement gap.

Marianne: I've spoken to teachers from every decade since the '60s, and they all agree that even when the schools were integrated, they failed to meet the needs of many Black students. Once the schools were segregated again, they failed Black students even more miserably. I've told you about the desegregation, the re-segregation of Sausalito Marin City schools started in the 1980s with the military bases closing down, and the number of white students dwindling to near nothing. At the same time, crack hit the streets of Marin City. Kids whose parents struggled with addiction, a lot of them had to take care of themselves.

The schools' classrooms were chaotic. New superintendents would show up every year from maybe Texas, or North Carolina, then take off for good as soon as summer arrived. It was 2001 when a group of white parents from Sausalito started their own school, a public charter called Willow Creek Academy. That is the charter school that grew and grew, while the regular public school shrank and shrank. Eventually, the attorney general showed up to say these two schools are separate and unequal. For 20 years, the two schools have competed for space in school buildings, for the sympathies of members of the school board, and most importantly, for the money and resources that board dolls out.

For 20 years, these two communities have told two completely different stories about how they came to be separate and unequal. You can imagine my surprise when I spoke to leaders of each of these communities late last year, and they told me, for the first time, the same story about what was going on. These are the only people who actually have the power to make decisions, the dozen or so people who make up the boards of each of these two schools. They said they were finally finding ways to agree with each other and move forward. They both told me the thing that was helping them the most-- Okay, it sounds so boring and bureaucratic, these two boards started holding joint study sessions.

Kurt Weinsheimer: I would say 20 joint study sessions from June until now.

Marianne: This is Kurt Weinsheimer, he's the president of the Charter Schools Board. He says they would just sit together in a Zoom room for hours and hours, week after week, hashing out the details of what kind of school they want to make.

Speaker 17: We're going to call this joint study session to order.

Marianne: You might wonder why they didn't do this from the start, just get in a room together and talk. My answer, after many months of observation, they couldn't. The fear and the anger that had built up between these two communities ran too deep. There was so much that needed airing. So many people, parents or grandparents, people who just care about Marin City or Sausalito, teachers, principals, coaches, school secretaries, so many people needed to get up in front of a mic in a school cafeteria, and speak.

Speaker 18: --Is that Marin City has been excluded.

Speaker 19: Are you going to ignore all the work?

Marianne: And to sit together in small groups and hear each other out.

Speaker 18: --A story that's not a Black and white story.

Speaker 20: I don't think our school sees our children.

Kurt Weinsheimer: Fights, arguments, raised voices, tears, et cetera, and that's what needed to happen.

Marianne: There's a type of couples' therapy where each side has a chance to list everything they're upset about, and until they're done, their partner has to keep asking, "Is there anything more?" There was one other thing that both Kurt and Itoco say made a huge difference, something totally outside of their control, the police killing of George Floyd and the protests that followed, including thousands of white Sausalito residents backing up their Black Marin City neighbors. Kurt says he saw Sausalito listening to Marin City in a new way.

Kurt Weinsheimer: People could really understand, "Wow, this is really real here." These things that were happening in the '60s, '70s, and were happening even up to current day, that I think was really eye-opening for everyone-- Not for everyone, it was eye-opening for many people that were kind of like, "Oh, come on, move forward, get over it." You realize these pains are deep and these pains are real, and you don't just get over it. We have a job as people trying to set up education, to make education a part of that healing process.

Marianne: In March, a year and a half after the attorney general laid out his desegregation order, these two schools announced officially that they will become one, open to all students this fall. Kurt and Itoco both told me that one of the watershed moments in their meetings was when their two boards finally finished a collective statement of purpose.

Kurt Weinsheimer: Can I read it to you? It says, "We are a district of choice that serves all pre-k to eighth-grade students and families, especially those with the greatest need for the opportunity to learn and lead."

Marianne: It goes on, but I think you've heard the most important part, the word 'especially'. Some of the people in the room were high-powered white Sausalito parents, perceived by others in the room to have created a school for themselves. Now, they were all together writing a purpose statement for their new school, and they all agreed it has to serve everybody, but especially, the students our schools have historically failed. There are still some sticky details to work out. Most importantly, accountability, how to make sure promises are kept, and that people from all four corners of this district stay.

Kurt Weinsheimer: I know a lot of families that are looking at private school, and that's their hedge.

Marianne: Most of the families from each community have said they will return to the new unified school. 20% of those students are Black, 26% Latino, 12% Asian, and 39% are white. Now comes the hard part, to make sure all of them flourish.

[music]

Kai: The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Joe Plourde mixed the podcast version. Kevin Bristow and Matthew Marando were at the boards for the live show. Thanks to Nora Gallagher for fact-checking this episode. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Karen Frillmann, and Christopher Werth.

Marianne: A special thanks to David Duncan, a PhD student in history at UC Santa Cruz, and many other sources who helped me with this story.

Kai: Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Veralyn Williams is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright. Of course, as always, I hope you'll join us for the live version of the show next Sunday 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it at wync.org, or tell your smart speaker, "Play WNYC." Till then, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.