Writer Darryl Pinckney on James Baldwin’s Love

Title: Writer Darryl Pinckney on James Baldwin’s Love [music]

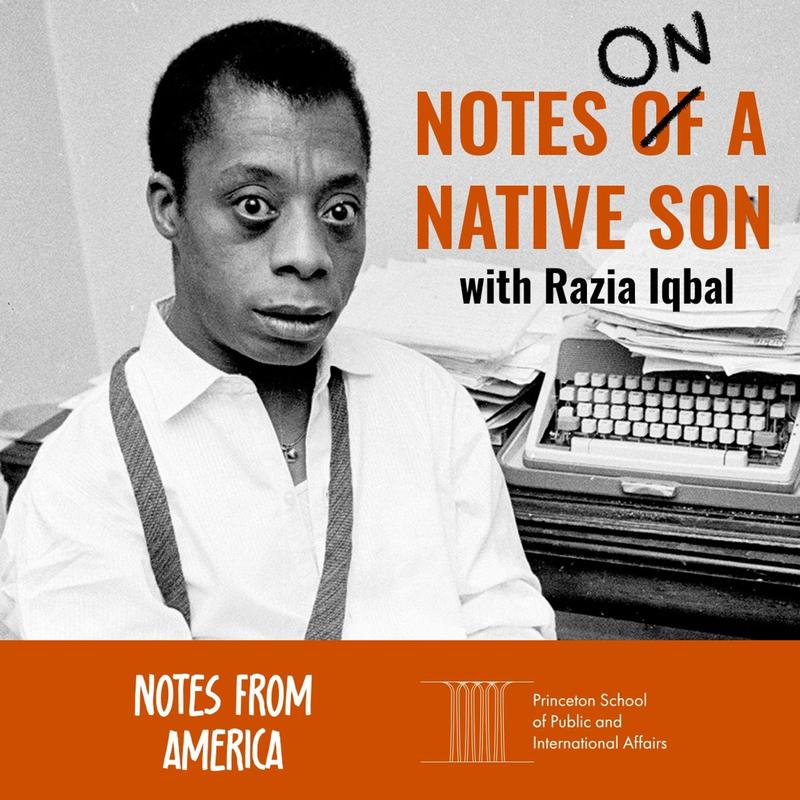

Razia Iqbal: Hello, my name is Razia Iqbal. Welcome to episode four of our podcast, Notes On a Native Son, about James Baldwin, because 2024 marks the 100th birth anniversary of a man unique in American letters, novelist, essayist, activist, prescient about race and racial politics in America, but also those connecting ideas, the idealized notion of the American dream, and what it actually means to be an American.

Who and what James Baldwin is, as well as his legacy, can't be listed, but it can and perhaps should be found in his work. An attempt to box him in is in any case counter to what Baldwin might say about himself. This podcast tries to get close to the idea of getting to know Jimmy Baldwin through his work and those who love his words. We called it Notes On a Native Son, after one of Baldwin's most famous autobiographical essays, Notes Of a Native Son. That essay clarifies with profound power what he is and what he thinks America is on his terms.

[music]

In each episode, we invite a well-known figure to choose a special or significant James Baldwin passage. The conversation that ensues tells us as much about Baldwin's story as it does about the person who loves Jimmy as he was known to all who loved him. Our guest on this episode of Notes On a Native Son is the writer and essayist Darryl Pinckney. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, and the Village Voice, and most recently, he's been the recipient of a highly prestigious award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters for his contribution to literature.

We met Darryl in Harlem, where, of course, James Baldwin grew up, though the neighborhood is quite different to the place Jimmy felt he had to leave in the 1940s. Darryl has been profoundly affected by James Baldwin ever since he first read him as a teenager, not least because Baldwin was openly gay and Darryl was thinking about his own sexuality. Today, Darryl Pinckney lives in a striking and sprawling house with the English poet James Fenton. He has a salutary tale about why one should never meet one's heroes, and rather joyfully for us all, his chosen Baldwin passage allowed us to delve deep into a big theme in his work, love.

[music]

Darryl Pinckney: The passage I've chosen from James Baldwin's work comes from Giovanni's Room.

[music]

"Until I die there will be these moments, moments seeming to rise up out of the ground like Macbeth's witches, when his face will come before me, this face in all its changes, when the exact timbre of his voice and tricks of his speech will nearly burst my ears, when his smell will overpower my nostrils. Sometimes, in the days which are coming--God grant me the grace to live them--in the glare of the grey morning, sour-mouthed, eyelids raw and red, hair tangled and damp from my stormy sleep, facing, over coffee and cigarette smoke, last night's impenetrable, meaningless boy who will shortly rise and vanish like the smoke, I will see Giovanni again, as he was that night, so vivid, so winning, all of the

light of that gloomy tunnel trapped around his head."

Razia Iqbal: Thank you, Darryl. There is something mesmerizing, not just in the language, but how you read that. Tell me first why you've chosen those sentences.

Darryl Pinckney: The first book I read by James Baldwin was Giovanni's Room. I didn't know really what it was or what it was about, but I remember how astonished my family was noticing that I was reading it.

Razia Iqbal: Because they knew?

Darryl Pinckney: My sister knew. I think for my parents, he was this guy who'd been in the New Yorker, but I don't know. Then over time, after I'd moved to New York and was part of the '70s, these lines really spoke to the time of everything seeming rather fleeting and it being more of a quest than actually getting there.

Razia Iqbal: How old were you when you first read it?

Darryl Pinckney: I was 13. How old was I when I imagined that I was living it out? That's college stuff. That mattered because the passage has this fatalism of first love, and once that love is over, so is love itself. You're never the same.

Razia Iqbal: The fact that it was same-sex love meant a lot to you.

Darryl Pinckney: Had a large part to do with it. I mean that David, the narrator or the protagonist is white and Giovanni is this rather Dark Italian. It's just part of the glamour of the story, and also, you can see projected Baldwin's type.

Razia Iqbal: I'm thinking about the juxtaposition of this being a book that you encountered at 13, which was about two men. Alongside that, Baldwin's insistence in his entire career, really to talk about this not necessarily being about homosexual love, but just it being about love that when you are afraid to love, if you run away from love, that's the tragedy.

Darryl Pinckney: He only wrote two essays remotely about gay themes and they were criticisms of a masculinity that would not admit to same-sex attractions or inner vulnerabilities, but this is Baldwin's rhetoric and he really addressed in his fiction all the time gay questions. That's where he dealt with it in his work. It's not Giovanni's Room that gives you a real picture of what he thinks, because I can't help but read it as this Lucien Happersberger memorial. That's perhaps a bit narrow of me.

Razia Iqbal: The man that he really truly loved.

Darryl Pinckney: In those Paris days. The two things fit as experiences. Certainly what happened must inform this book.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: To go back to the seminal nature of the impact that this book had on you, you read it when you were 13. Your sister knew what this book was about. Your parents saw Baldwin as somebody who had a presence as a writer in a literary magazine. Just describe for me when you started to feel, "Okay, this is a writer I want to read more of. I'm intrigued. I want to explore some more."

Darryl Pinckney: In high school, a teacher gave me a copy of the New York Review of Books that had in it Baldwin's open letter to Angela Davis.

Razia Iqbal: This was when she was in prison.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. That had a terrific impact on me. Then in college, you're picking up a new book a day, and I read Notes Of a Native Son, and it was not like anything I'd read.

Razia Iqbal: This is the essay about his father. I think it's also a political--

Darryl Pinckney: Yes, but actually, the whole book, it was a very important discovery and one you just make on your own, which used to be part of the adventure of being at university, people told you about things you didn't know, professors, friends.

Razia Iqbal: How did that then become something more for you? I suppose what I mean by that question is the idea that Baldwin then became a lifelong companion, if you like.

Darryl Pinckney: The '60s were not quite gone and the '70s when I first read them. The questions that decade raised, and where was the civil rights movement, really hung over the conversations I didn't necessarily took part in, but heard of through my sister and my parents, who were very active in the NAACP and other organizations, that my sisters would argue with my parents, and I would stay out of it.

Because of Angela Davis, I was some completely ignorant Marxist but I had then at college, these roommates were very intense, and so you do end up reading a lot of Marx and Hegel not sure what you actually understand, but Marx was a very persuasive writer. Baldwin was often attacked in those days, but also there was a real prejudice at this time that his anger had burned out his talent.

I'm fascinated that that wonderful Raoul Peck documentary actually takes off from the work that, when it came out, was taken as a sign of his diminishment as a writer because it was so uncompromising, "I don't believe in the wagons that bring the bread of humanity anymore," and things like that. He always had, to me, excessive moments. He's denouncing Chartres and Shakespeare, and I don't take that seriously.

Razia Iqbal: [laughs] When you say you don't take it seriously, explain a little more.

Darryl Pinckney: He was a very cultured soul. Not in a pedantic way, but he read everything. He's not jettisoning Shakespeare at all. He's just taking a stand and he's attacking Chartres as this-- I can't even pronounce it, but something in which the French take great pride. He's also, once again, rebelling against Christianity and the canonical, as we would call it now, but I didn't quite take it seriously. No.

Razia Iqbal: The rebelling against Christianity is interesting, isn't it? Because so much of his writing, particularly in his novels, but also in the rhetoric of his essays, the cadences of having been a preacher are very present and central.

Darryl Pinckney: People say that. I think the presence of having read everything is really as strong.

Razia Iqbal: Both could be true.

Darryl Pinckney: He has a wonderful ear. I think certainly the church and the pulpit and speaking has a lot to do with it, because as beautiful as his prose is, it's always sayable. There's a speakerly voice in Baldwin's eloquence. It's not decorative and it's not a display. It's a disclosure of his personality, which was this mad, rather generous, sensitive observer.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: The notion of being an observer, of course, is central for every writer. I'm thinking specifically about the relationship that Baldwin had with the painter Beaufort Delaney, who changed his life, partly because what he showed him was the importance of observation.

Darryl Pinckney: To trust your own vision or your own destiny, to live out your choices. He was also someone who needed his help, and I think that was a very important thing. He clearly believed in the work, but I think it had something to do with the bravery of living out your choices and work having no reward outside of itself, though he was, of course, ruinously extravagant, but a lot of it had to do with supporting an entourage.

Razia Iqbal: I wonder whether that made him also quite glamorous.

Darryl Pinckney: He was extremely glamorous. There's no question. No question. The guy could talk, and he had such presence. I saw him only a few times, but I certainly didn't know him.

Razia Iqbal: You read Giovanni's Room at 13, read lots more Baldwin when you were at college.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes.

Razia Iqbal: Was there a moment that was a little bit like the moment when you read Giovanni's Room later that you really felt that this was a writer who meant something more to you?

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, you can't read the title essay Notes Of a Native Son without marveling at the way things fall beside one another with him doing very little to make it so. His father's death and the birth of the last child and the Harlem riot and his awareness of his own need to go. It's it's in a real American literature.

Razia Iqbal: You mentioned that you had only encountered him a few times. Are there specific moments in those encounters that you--

Darryl Pinckney: Each one embarrassing, I promise you.

Razia Iqbal: Say more. Share with us.

Darryl Pinckney: He was in the Gingerman restaurant near Lincoln Center, and I ran over to him and I said, "Hello, Mr. Baldwin. Blah blah blah. My professor is blah blah blah." The only book I had with me was a volume of Byron's journals, which I opened for him to sign, and he very gracefully did.

Razia Iqbal: That's so sweet.

Darryl Pinckney: It was this asshole move number one. He was very forbearing on each occasion.

Razia Iqbal: Asshole move number two.

Darryl Pinckney: I may leave that one out. That was really bad.

Razia Iqbal: Oh, come on. Come on.

Darryl Pinckney: No, I can't. It was really terrible. I'd written about Just Above My Head in the New York Review of Books.

Razia Iqbal: Which was one of his later books.

Darryl Pinckney: Which is one of his later books. I mocked it for treating the homosexual couple as a married pair. Of course, what everyone wanted was to get married. He knew and I was wrong. He very graciously said, no, he hadn't read it.

Razia Iqbal: You asked him directly?

Darryl Pinckney: I asked him directly. Can you believe it? Just sitting here telling you, this is going to be with me all day. I've ruined my own day. He was very sweet about it. He'd written things about people and then faced them. He was just not a fool, but I was.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: We'll take a short break. More from Darryl Pinckney when we come back. This is Notes On a Native Son with me, Razia Iqbal.

[music]

Suzanne: Hey, it's Suzanne. I'm a producer with the show. Back in January, we were live at the Apollo Theater in New York for a celebration of Martin Luther King Junior and a conversation about the politicization of the word woke. That show could win a Signal Award for best live podcast recording, but we need your help. Community voting for the Signal Awards is open right now and we would love it if you could take a moment to show your support for the show and send us a vote.

It's really easy to do. Check out the link in the show notes for this episode or visit Notes with Kai on Instagram and click the link in the bio. Select Notes from America with Kai Wright and that's it. It's super easy. Thank you so much for listening and for voting. Now let's get back to the episode.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: You're listening to, Notes On a Native Son with Razia Iqbal.

[music]

We're sitting in your astonishingly beautiful home in Harlem and we were trying to decide which room we were going to record this conversation in. I have noticed just over your left shoulder, all of your books, we're surrounded by books, are in alphabetical order and the Baldwin shelves are right behind your right and left shoulder.

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, well, very nice.

Razia Iqbal: I feel like there is something synchronicity, serendipitous about that. I love that.

Darryl Pinckney: I looked at some recently because it's, of course, his centenary, but what most strikes me is that his Harlem is completely gone. That's now history. He's describing a real gone world.

Razia Iqbal: When you say that that history of the Harlem that he grew up in has gone, has it also gone in the sense that it has been erased? There are no remnants of it?

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, would there be remnants of tenements? All the delis are Yemen, not Jewish. Harlem always had a fair number of Black homeowners, but now it's a very integrated area. You could say much less Black, the percentage, but the historic Harlem of being overcrowded is gone. The street life is very different.

There are no bars anymore at all, really. It's more like the rest of New York, but a New York that's also changed where street level, you eliminate lots of little buildings and put a big glass one.

Razia Iqbal: I'm always intrigued in my own mind as a young South Asian woman growing up in London and why I was drawn to Baldwin in my teenage years in the way that I was. I think the older I got, the more I read him, the more I realized that actually, it was nothing to do with where he came from. It was to do with the very real sense that he gave anybody who read him that he was a writer's writer. He was presenting a universality of feeling, emotion, political solidarity.

It didn't matter that I was not African American and I couldn't locate my experience in his. I'm so grateful for that because it's so far removed from my own experience, and yet it is absolutely central. He is absolutely central in my life.

Darryl Pinckney: That's wonderful to hear because he didn't grow up with this sense that you can only read if you see yourself there. I think he always read to take a journey. I think that's why he liked Stevenson so much in his childhood. He understood that a book was a journey.

Razia Iqbal: Is that what it is to you? Is that what literature is to you-

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, yes.

Razia Iqbal: -and your connection with him in that way, too?

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, yes. Mary McCarthy was very surprised by how much he'd read, which I always found a bit--

Razia Iqbal: Patronizing is a word that comes to mind. [laughs]

Darryl Pinckney: Maryish.

Razia Iqbal: [laughs] She was who? Just explain who she was.

Darryl Pinckney: Mary McCarthy? She was a very famous writer in the '60s and the '70s and a really good one, I must say. Her reports from Vietnam I think one day will be appreciated.

Razia Iqbal: Is it innate racism of a very particular kind that presumes that a Black person would not be well-read or as widely read?

Darryl Pinckney: I think it's the widely read, that you assume they've read in their subject, and that's something Baldwin resisted for a long time, but that he was reconciled to. It was a very big recognition for me as well because it just was, but it wasn't an obstacle. It actually was in some ways, I don't want to say an advantage, but when I was growing up, the subject was so real and urgent that you were immediately at the center of something, and people asked your opinion, which meant that you had to know something. I began to read things and I'd been to-- I don't know what, in college to read, but also all that Rambo and Sylvia Plath, it was wonderful.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: It does also occur to me time and again when I read Baldwin that while he, as you have so wonderfully articulated, became this glamorous figure who was a spokesperson, was a television personality, lit up a room when he walked into it, used his charm in so many way, that in the end, one of the things that is absolutely central to what he wrote about was love, which takes us back to Giovanni's Room.

Darryl Pinckney: Yes. He was slightly made fun of by Hannah Arendt for stressing the importance of love. Maybe for him, it wasn't a weird thing to say. That's a real church view, but it's also a real church evasion that you send people home with this opiate. She rather said something like, "He'll find out that people who come to power aren't nice no matter what their former condition was." I don't think he ever conceded that point to her. He really always insisted on the transformative capabilities of individuals in some ways over society or in spite of their societies.

"Until I die there will be these moments, moments seeming to rise up out of the ground like Macbeth's witches, when his face will come before me, this face in all its changes, when the exact timbre of his voice and tricks of his speech will nearly burst my ears, when his smell will overpower my nostrils. Sometimes, in the days which are coming--God grant me the grace to live them--in the glare of the grey morning, sour-mouthed, eyelids raw and red, hair tangled and damp from my stormy sleep, facing, over coffee and cigarette smoke, last night's impenetrable, meaningless boy who will shortly rise and vanish like the smoke, I will see Giovanni again, as he was that night, so vivid, so winning, all of the

light of that gloomy tunnel trapped around his head."

[music]

Razia Iqbal: When we invited you to take part in this, did you think immediately, "This is what I'm going to choose," or was it hard to choose?

Darryl Pinckney: No, I thought this was what I would choose because it's stayed with me all these years. Just the promise of youth and the search for love. It's like a photograph that when you take it out and look at it, everything rushes back, just those lines. They're very Baldwin-like. They go where they're going and you trust them.

Razia Iqbal: Daryl Pinckney, thank you so much for speaking with us.

Darryl Pinckney: Oh, thank you. [inaudible 00:28:04]

Razia Iqbal: That was great. Thank you so much.

Darryl Pinckney: It's Baldwin. It's such a relief to talk about someone you like. Do you know what I mean?

Razia Iqbal: [laughs] Yes.

Darryl Pinckney: This is the only centenary moment I have, so I'm grateful to you for that, pay my tribute to him.

Razia Iqbal: Thank you.

[music]

This has been Notes On a Native Son, podcast about James Baldwin. In the next episode, we'll hear from the Turkish writer Elif Shafak, not least about what Istanbul meant to Baldwin and what it means to her. This podcast is brought to you by WNYC Studios and sponsored by the School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University. It is a Sea Salt and Mango production produced by Tony Phillips. The researcher is Navani Rachumallu.

The executive producer for WNYC Studios is Lindsay Foster Thomas, and Karen Frillman is our editor. Original music was by Gary Washington, and the sound designer and engineer is Axel Kacoutié. Special thanks to Dean Amaney Jamal of Princeton University.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.