The Gifts of Mortality and Movement, According To Dance Legend Bill T. Jones

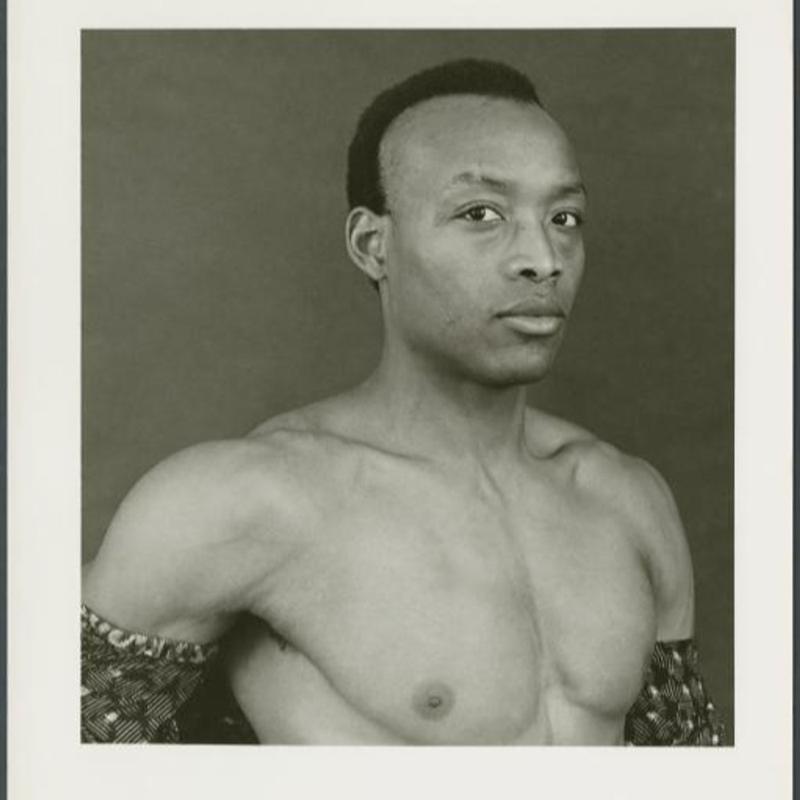

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. You do not have to be a devotee of dance to know the name Bill T. Jones. His face has been on the cover of TIME Magazine. President Obama gave him a National Medal of Arts, and Keith Haring painted his body, like painted on his naked body. Suffice to say, Bill T. Jones has lived quite a public life. For most of that life, he's been a dancer and a choreographer. At age 72, his body remains striking. He's over 6ft tall. He's muscular. He's got these high cheekbones.

He moves quietly but with command. He is a presence. The Brooklyn Academy of Music is restaging one of his most renowned dances this fall. It's called Still/Here. It's a dance from 30 years ago, and I went to talk with him about it. Hello. Hi.

Bill T. Jones: Hey.

Kai Wright: I'm Kai. We're going to spend the whole hour with Bill talking about creativity and life, and ultimately about death.

Bill T. Jones: I thought you would sit on the couch and you can have--

Kai Wright: I met up with Bill at his house. We sat in his living room. He lives about an hour outside of New York City. With the windows open, you can sometimes hear a distant train, but mainly you just hear the cicadas. It's a really peaceful setting, almost a refuge for someone who has spent so much time literally burying himself before the public eye. Were you always aware of the fact that, I mean, you're a famously beautiful man, right? That is a thing that is part of what people think about you as soon as they think of you. Were you always aware of that?

Bill T. Jones: It took me years to realize that people were thinking that? But anyways.

Kai Wright: That was the question. Is that something you were aware of all along or is that--

Bill T. Jones: Yes. First of all, what was beauty in a Black household? Beauty was Gary Cooper. First of all, men were not beautiful. They were handsome. Women were beautiful. Now, did I know that? I knew that I could run, I could jump. So where was my sense of being a beautiful person? Women helped a lot. I think there was something in the touch of a woman and the eyes of a woman. There were very few men around who could look at me approvingly and not compete with me or not be suspicious of their feelings toward me.

There were women of every of your color, Black and white, who would do that and I think that was confusing for many years. Then you meet Arnie Zane.

Kai Wright: Arnie Zane was Bill's longtime collaborator and longtime lover. They met in college at a state university and danced together starting in the 1970s. In 1982, they established the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company. Their dance company was part of an exciting new wave in dance choreography. This exploration of the vocabulary of movement and just redefining the landscape of this art. Then Arnie died of AIDS-related lymphoma in 1988.

Bill T. Jones: I remember when he was dying at the hospital, and I was literally living in a room with him. A friend of mine, Robert Longrow, he actually booked me a hotel room so I didn't have to make this trek up and down every day. I remember the sadness of the situation, and I was losing him, who'd always been an engine in the relationship. Let's face it. He was. I remember that looking at myself in that mirror in the hotel and saying, "This is the body that he loved and if you love him, then you have to take care of this body."

That was a very important thing when I met him, that there was somebody who loved my body.

Kai Wright: Bill grew up about 4 hours from where we're talking. He's from western New York State.

Bill T. Jones: I think people are surprised to find out that I'm not an urban Black person. Oh, where are you from?

Kai Wright: I'm from Indiana, Indianapolis.

Bill T. Jones: Indianapolis. That's urban though, right?

Kai Wright: Yes.

Bill T. Jones: Okay.

Kai Wright: But you are an upstater.

Bill T. Jones: I'm born in Bunnell, Florida, and I was K-12 in Finger Lakes region, little town called Wayland, New York because we were migrant workers there.

Kai Wright: Your parents were migrant workers there?

Bill T. Jones: Yes. I spent time in potato fields as well.

Kai Wright: Did you? I didn't know that.

Bill T. Jones: Oh, yes. Near the Finger Lakes.

Kai Wright: Is it a special place to you? We don't--

Bill T. Jones: It is. Believe me, I'm quite romantic about these things. I ask people sometimes, what is the place that you dream about, that comes through in your dreams? It is that house on Miller Road. 12 kids, 8 boys,4 girls. I'm the end of that, actually. A lot of who I am today is because of those folks there in Wayland, New York, those German, Italian folks. Their school was drama teacher, band practice, chorus. They took care of us in a way. The education was not bad. No. We were singing six eight-part harmony to the St. Matthew's Passion when I was in high school.

I was a pretty good athlete with my brother Azel, who was driving me. He wanted me to go to the Olympics and all. Athletics was just what you did as a Black body. I shouldn't say that. Maybe it wasn't true for my older brothers. They were too busy hauling potatoes and chasing girls.

Kai Wright: That's what you did with your body.

Bill T. Jones: Yes. That's what I did? You're right, like I said.

Kai Wright: Were you always in your body? As you recall, at that age, were you always aware of your body and it's-- I don't know, is utility is the word.

Bill T. Jones: Kai, we're coming at this from the psychological point of view, and I say, hell yes. Also as a young man finding his sexuality and so on, a lot of the body was this secret place that nobody should know the things that were going on in the mind and the body. All of this was going on in this body that we now call Bill T. Jones.

Kai Wright: I ask these questions for selfish reasons. I have a very particular memory of struggling. I'm still kind of struggling to be in my body, to be in my Black body at that age. I think about people like yourself who are so conversant about and with their bodies and think, how did you get there?

Bill T. Jones: You had to learn now, of course. Don't you think you have to learn now? Did this body that is Bill T. Jones see himself staying there? No way. The world was calling, "Go somewhere else."

Kai Wright: I promise we will get to Still/Here. I am curious also in that finding the world, your time at SUNY Binghamton, when you and Arnie Zane first started making work. I've read adjectives like colliding, anarchic, and angry.

Bill T. Jones: Yes, all of the above.

Kai Wright: Are those the right adjectives?

Bill T. Jones: Now we're talking.

Kai Wright: I'm wondering what your emotion was at the time with that work.

Bill T. Jones: What you're trying to get at is the phenomenon of Bill and Arnie. How in the hell did that happen? He and I met at the pub downstairs one night, and I was in what I thought was post-Woodstock hippie drag. Jimi Hendrix was my patron saint, as it was probably for a lot of young guys. I've never asked at Gates about that. I don't know if he was ever a rock and roller, but I was. Jimi Hendrix was an example of how you could be authentic and cool and they say the revolution and you're not your body. Look at him.

He's with all these white people and he's totally comfortable and he rules and so on. I am there at the university, dressed in that way on a Friday night at the pub. Should have been studying, probably, but everyone was doing it. Across the room, I see this small unusual, because he was dressed in a very beautiful knit sweater, which, as I understood later, was probably made in the '30s, and he had bought it in Amsterdam at the flea market. Hair was short at a time when everyone else's hair was long. He had this kind of allure about him. He was what we'd call now gender nonconforming, I think.

Kai Wright: You both were a little.

Bill T. Jones: Pardon?

Kai Wright: Based on the pictures, you both were a little gender-nonconforming.

Bill T. Jones: Oh, I don't know if I was, but he told me that I wasn't a liberated man. He would wear the clothes he wanted to wear. I don't know what you see in the pictures, but what I thought we were projecting was the counterculture. Antique clothes, you could have spangles on them or what have you. Arnie, of course, was much more sophisticated. When we began to be lovers, and I didn't know that's what that was, I was definitely a young bisexual man at that time. He said, "Why don't you get serious about what do you want to do?"

Very important. My God, I know people who have already died who never got to answer that question. What were they really doing? He was saying, "What are you? Are you an actor?" Then I discovered this thing called dancing. He said, "You got to be dancing." My niece Marion, she said to me one day, "Don't go to track practice. Come to these African dance classes." I went, and I was besotted. At the same time, Martha Graham's company came and, wow, there's a whole world where people move. It's not the June Taylor dancers on Jackie Gleason Show.

It's not James Brown getting on the good foot and what have you. It's not the dancing that I had seen from Black field workers. It was something else. Dance as a communicative medium. That's our little pompous, isn't it?

Kai Wright: No, because one of the things you've said about that, that I was drawn to is this idea that movement closes the gap between the mind and the body.

Bill T. Jones: Did I say that? Oh, God knows with the battles I've had psychically, now I wonder about it. No, you're right, I still think that.

[MUSIC - Bill T. Jones: Still/Here]

Kai Wright: Bill went on to be recognized with a MacArthur Genius Award and two Tonys, and he kept the company he started with Arnie going. Now it's called New York Live Arts. Next month, the company is restaging a work that was first performed 30 years ago, called Still/Here. We'll hear more about that dance after a break. This is Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and today I'm at the home of Bill T. Jones, a world-famous choreographer and dancer whose work I have followed my whole adult life.

One of his dances, Still/Here, is about to be restaged at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. It opens at the end of October. After his partner Arnie Zane's death and after the loss of so many young gay men to HIV and AIDS, Bill T. Jones went in search of a choreography that spoke to our mortality, but also to the meaning of our lives. He began talking and moving with other people who were also facing death through terminal illnesses. He created survivor workshops, which allowed him to explore this new vocabulary of movement.

In the original program for Still/Here, Jones writes, "My intention since the onset of this project has been to create a work not as a rumination on death and decline, but on the resourcefulness and courage necessary to perform the act of living." The journalist Bill Moyers was so interested in this inquiry that he made a documentary about Still/Here and about the workshops that led up to the performance.

Bill Moyers: What do you hope to accomplish at a workshop like this?

Bill T. Jones: I want these workshops to be moving and talking about life and death. I want to see--

Kai Wright: That Moyers Doc is really worth watching. We'll link to it in our show notes. When I watched it, I kept thinking about the cultural moment in which this work was made. Still/Here?

Bill T. Jones: Yes.

Kai Wright: For people being introduced to the work, how would you describe it?

Bill T. Jones: It is at once a period work that is proving to have transcended its era. It came out of the personal questions and travails of its primary creator, Bill T. Jones, about the nature of mortality at a time when many, many people's lives were being cut short. It transcended even being a piece about death to be how aesthetics, beauty can illuminate the ideas of life and death, how to be enduring at once still, but to carry on and then slash here. Where is here? Do you know where you are? Still/Here. That's how I answered the question of fear of death and staying committed to a future.

Kai Wright: Actually the question of a fear of death, coming out of Arnie's death, thinking about your own death?

Bill T. Jones: Yes. I could say, yes, it came out of Arnie's death, but you have to realize there was a whole culture of death at that time. I ran into this again some years later. I was asked to make a piece about Abraham Lincoln, and you talk about Abraham Lincoln. You're talking about the Civil War. The Civil War was an era drenched in the most morbid poetics. Literally, the corpse, the young body, just should be living, and it is dead. Grieving women, all of those things. There was something about the AIDS crisis in New York that set the stage for that.

Kai Wright: It's so evocative to think of it as I've written and lived and discussed and done so much on this epidemic. I never thought about it in the context of the Civil War and that kind of mass death and the cultural experience of it.

Bill T. Jones: Your comment is well placed, because I say to people that it became apparent to us it was almost a gift, that every generation had its tragedy, its purging of its young. There was, at least in our country, there were. Let's call it the Civil War, but there's also World War I and II with thousands of people just cut down. This is what yours looks like. It was a little odd because they were heroes, and we are reprobates. We are decadent, and we deserve it because we are not good people, and you get what you deserve.

I was a very public person, rich at HIV, and Arnie's death had been very public but I did resist saying that Still/Here was directly that. Where did the idea come from? There was a woman who was a breast cancer advocate named Sunny Dupree. I don't know how I happened to be at her house in Cambridge, but she said, "You should make a piece about it." I said, "I don't know. I'm a gay man." She said, "That's why you should do it." Rather than make a piece about breast cancer, I thought, let's make a piece about mortality and the fragility of the body.

Then you began to look at the world in a different way And that's when our "survival" workshops started.

Kai Wright: Where did that idea come from? The piece grows out of these workshops.

Bill T. Jones: Let's back up. Our goals in the survival workshop were twofold. I said to this group of people that had been collected by our presenters and our supporters in the community, I said, "I am not a practitioner of any kind. I am a man who needs his hand held." I didn't tell them that. I was also hoping that they would give me something which was about movement. The people knew I was there to ask their help but did they also know that I was thinking about them being a material for choreography? Yes, I was thinking that from the beginning.

Kai Wright: They did not know that.

Bill T. Jones: They didn't know it, really. Now, did anyone ask me, "Why is a choreographer doing this? Why not a playwright?" They were open. I'm so glad they were trusting.

Kai Wright: Do you think that openness is self-selecting in terms of the type of person that would accept that invitation? Do you think that openness had something to do with the fact that they were seeking a space to wrestle with mortality? What do you think?

Bill T. Jones: All of the above.

Kai Wright: In the Moyers documentary, you can watch Bill in the workshops as he asks the participants, "Tell me about your life right now in one simple gesture."

Bill T. Jones: I remember a person whose name was Floyd, a wonderful Black man, a retired worker in Ohio, hip kind of guy. His shape was to snap and say, "Floyd, I like jazz." That was his description of himself but then he whistled in most beautiful way, "We'll be together again." [sings] It was so magical. He just offered that, and it is a wonderful gem of an idea that we brought back into the piece.

Kai Wright: 12 workshops took place in 10 different cities across the country. Almost 100 people participated.

Speaker 3: James, Sam, Michael.

Kai Wright: They ranged. They ranged in age. Some were 70, some were children. They were all different races. They were women, they were men, they were queer, they were straight. They were all people who were dealing with life-threatening illnesses themselves. They had firsthand experience of mortality. Bill walked into the room, most often he was just wearing sweatpants and a sweatshirt, and he got people moving.

Bill T. Jones: Whoa.

Speaker 4: I'm going to drop you. I'm going to drop you.

Bill T. Jones: Can you put me back?

[laughter]

Kai Wright: Then he would start asking questions.

Bill T. Jones: How do you get up every day? How do you love your children? What have you learned about life? What are you afraid of? And so on. These became the script for these sessions. They were not primarily people who were dancers. That was a wonderful thing about it.

Kai Wright: They seem so intense. I mean, it seems like such an intense experience.

Bill T. Jones: Have you seen the Moyers?

Kai Wright: Yes. I had to turn it off a couple times, if I'm honest.

Bill T. Jones: I'm just now to the point where I can watch it, but it-- Yes.

Kai Wright: Do you remember the first workshop? Are you able to tell me the story of the first one and what that was like?

Bill T. Jones: I think the very first one in Austin, Texas. We didn't know what we were doing, but I remember one codger, old codger. I'm an old codger now. The codger saying, "I came down here because they told me there's going to be some dancing girls." He was a lovely man. They all came in. It's a big studio or a gymnasium. We began to do certain exercises like draw your life on a piece of paper. Where do you start? Now make a pattern. It became a roadmap. Now walk your life. Now I need a volunteer who is actually going to walk us through their life.

Complete guided tour.

Speaker 4: Speaking?

Speaker 5: With narration?

Bill T. Jones: With narration. Now, did we do in that first workshop, Take Me to Your Death? I remember it happening in Boston quite clearly, in Boston might have been the third one. Can you imagine the last moment of your life? What's the last thing you--

Speaker 4: The light.

Bill T. Jones: The light?

Speaker 4: Yes, the light. I watch the light, the sun shining.

Bill T. Jones: That's an exercise not many of us actually are so interested. Maybe now I imagine there are but that time, it was kind of a macabre exercise.

Kai Wright: To me, it remains a macabre exercise. I can't do it.

Bill T. Jones: Really? You can't at all? Do you dare when you feel most secure in yourself? I said, okay, what would you like it to be? Ah. What would you like it to be?

Kai Wright: One of the things you would ask people in the workshops was what they love.

Bill T. Jones: Yes. What they love.

Kai Wright: Why was that an important question?

Bill T. Jones: I think it implies their highest self. Love is that faculty of being human that gives one a direction out of self. Parents know this. If you love anything, I think you understand that sometimes you're given the blessing of forgetting the self. Love quiets those questions, if only temporarily. Could I trust a person who has never had the experience of loving?

Kai Wright: If they couldn't answer that question, yes, it's true. You haven't given yourself over to anything.

Bill T. Jones: That's where art comes in. All of the songs are gleaned from these discussions, asking people about what they love and the moment of diagnosis when their world changed. Then they were set to music. That's what the art is.

Speaker 4: No control. The doctors are in control and they feed me poisons which are working, but I have no control. The doctors are in control.

Kai Wright: Bill's art was turning what happened in the survivor workshops into the dance, Still/Here, the movements, the gestures, the expressions that Bill encouraged the workshop participants to make, they became part of the actual choreography of the piece. Bill's dancers would perform gestures that people made in the workshops. The words from the workshop participants, those became part of the music for the piece.

Speaker 4: There is birth and there is death and then between there is light. The joke is, God doesn't tell when you're going to die.

Bill T. Jones: The second section is by Vernon Reid. And Vernon Reid is a rocker from Living Colour, if you remember that group.

Kai Wright: Yes, indeed.

Bill T. Jones: A wonderful man. One day in a workshop, which is a very good workshop, we're in the studio having this intense time, and somebody next door is doing construction with a drill.

Kai Wright: You're here talking about death and love, and all of the things.

Bill T. Jones: Yes. As a matter of fact, things like a woman talking about-- she was a wonderful woman. She was an actress. Mortality and knowledge. I just feel it. You remember that?

Speaker 4: Only if I knew enough or if I understood enough, maybe I could accept mortality, if I could just get the right perception, if I could just find the thing.

Bill T. Jones: Your movement is a question.

Speaker 4: Yes, it's a struggle. I'm struggling between knowledge and--

Bill T. Jones: If I just had a knowledge, I could understand mortality, I could deal with it. This drill is going on, but he brilliant, he put that in the score. That's something we call the pit in the story. It's harsh to look at, and that sound is so grating, but it is justified because, no, this is not a piece that's all about gooey emotion. I know people who are not fans say it's maudlin and what have you, but it's pretty hard-hitting. It hits almost every angle. Tawny was a young white woman. I think she was also in that Iowa workshop, who had cystic fibrosis.

A delightful person, but she was literally-- cystic fibrosis, you're drowning and your lungs are drowning in phlegm, I believe. She was talking about, "Why am I alive?"

Speaker 4: Why the hell me? Why do I have cystic fibrosis but not only why do I have cystic fibrosis, why am I still living? All my friends that I grew up with, with cystic fibrosis and been in and out of the hospital with are all dead.

Bill T. Jones: I said, "What do you love?" She said, "I like pizza. I like sex, but I haven't had very much." She said, "I would like to have sex. I would like to have love." She died shortly after that.

Kai Wright: Oh, really?

I don't think she ever saw the performance when it came back through the town.

Bill T. Jones: Kai Wright: Oh, wow.

Bill T. Jones: Her parents did. Is that true?

Kai Wright: Bill looks up past me to the other side of the room. After making us tea, Bjorn Amelan, who is Bill's current husband, had sat down and was working on a table behind us, carefully painting this detailed work on a big canvas that was spread out. Bjorn and Bill met in 1992.

Bill T. Jones: Bjorn is saying that she died two weeks after she did her last what?

Bjorn Amelan: She did a cartwheel in our workshop, and it was the last time.

Bill T. Jones: She didn't think she could do a cartwheel.

Kai Wright: She had done a cartwheel at the workshop.

Bill T. Jones: Yes, and that became this--

Kai Wright: Wow, and died two weeks later.

Bill T. Jones: Yes, died two weeks later. Man, it was real. It is real.

Kai Wright: I'm so envious of the experience. I can imagine all of those people being willing to share that level of vulnerability and the things you learn about the world, about yourself, and how you [crosstalk]

Bill T. Jones: Not knowing where it was going. Not knowing how it was going to be realized. Isn't that amazing?

Kai Wright: It really is remarkable.

Bill T. Jones: Generosity, I think, is the word. Those persons, they gave to me some of the greatest things to give. I've tried to honor it, and I think about it a lot now. I think about it.

Kai Wright: The moment of death now, or you think about the workshops now?

Bill T. Jones: The moment of death. Oh, yes. Still/Here didn't stop. It was like a moment where an idea came in close on an idea, but my own life and engagement in the topic did not stop.

Kai Wright: What do you think about it now?

Bill T. Jones: That I should embrace it as being a part of-- It's like my next breath. It's inevitable. Can I normalize the mysterious? Can I know that there was a time before I had consciousness, and it's inevitable there's a time after? All of these things are comforting to me, but they don't take away the deep-in-the-night terror. What takes away the deep-in-the-night terror is the sound of my husband next to me, breathing evenly. Look at this room. Look at this garden. It balances out.

[MUSIC - Bill T. Jones: Still/Here]

Kai Wright: I'm talking with Bill T. Jones at his house just north of New York City. He's talking about his dance Still/Here and the work that led up to creating that dance. Coming up, we'll hear more about the reaction to this provocative work when it debuted. This is Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. Stay with us.

Katerina Barton: Hey, it's Katerina Barton from the show team at Notes from America with Kai Wright. Something happens to me when I listened to this show. No matter the topic or the guest, I can always think of someone I want to tell about what I just heard, and I do. If you're thinking about who in your life would enjoy this episode or another episode you've heard, please share it with them now. The folks in your life trust your good taste, and we would appreciate you spreading the word. If you really want to go above and beyond, please leave us a review.

It helps more people, the ones you know and the ones you don't find the show. I'll let you get back to listening now. Thanks.

Kai Wright: This is Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and you're joining me in my conversation with Bill T. Jones. His work, Still/Here, is being remounted next month at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, what we call BAM here in New York City. 30 years after its debut, the dance was based on survivor workshops that Bill held around the country with people who were living with life-threatening illnesses.

Bill T. Jones: Now I'm going to ask you to do something which is more difficult to do. Take me to the end of your life. What's the room like? Who's there with you? What time of day is it when you're-- the final day? What time of day is it that you leave?

Speaker 7: Early evening. It's early evening usually, I guess, about the time Roseanne is on. I like it.

Kai Wright: For many people, participating in the workshops was transformative. They knew they wanted to be there, but it wasn't that way for everybody.

Bill T. Jones: There are other people who were really petrified. "I don't know why I'm doing this. My friends told me I should do it, but I'm not sure if I should." To be sure, there were people who felt-- There was a man who was very, very ill. Was it in Ohio? His name was Robert, and he was-- What's the word? Desultory. I loved having him there, but he was very depressed. He died. His companion, when we came back to do the piece, really let me know that he thought that something had been off about using Robert when he was so down, as if I had somehow stolen something.

Or women who saw the piece with my fantastic women and said, "I'm a breast cancer survivor. Those with their healthy young breasts, how dare they try to embody my experience?" There are people like the woman in Ann Arbor, I believe. Not Ann Arbor or who French woman. She was dealing with cancer, and she was wonderful in the workshop. I remember her holding an invisible ball and saying, in her shape, "The earth is my mother. She comforts me." Then you have videos of her showing what flying looks like. It's just silly movement, but slowing it down.

Her daughter has contacted me years later, who's now a choreographer. At that time, she must have been an infant, and that was the mother's sadness, that she was going to have to be leaving her infant child. That daughter, and I hope she comes forward, she has written me. She felt that it was important for her mother to have done this, and she was grateful. A gift had been given.

Kai Wright: It was first performed, Still/Here got a lot of attention. The New York Times described it as a true work of art, both sensitive and original. For the last 30 years, Bill has also been churning in his head about the other reaction the peace got.

Bill T. Jones: There was a stink about it. There was called victim art and so on. It was confused with identity politics and the "laziness" of our generation, our era. That art is not something utilitarian to be used for social causes or so on. Art should transcend. Art has got to be disinterested.

Kai Wright: This is an idea you are disdainful of.

Bill T. Jones: I wasn't disdainful. Quite frankly, I'm a bit of a snob myself. I thought that I was down with it, but I thought that it was just a grand tradition of taking experience of life and through processes of construction, investigation, and analysis, you make something else. Art coming out of your identity as a Black man, your art should transcend all those things. It comes out of your experience as a woman, as a person who's been molested. That's pure indulgence, and it's cheating.

Kai Wright: I can't imagine, you know, so as a Gen Xer, my blood goes entirely cold at the idea of art that has nothing to do with who you are.

Bill T. Jones: Now, they say it starts there, but it's got to climb to the Apollonian Heights to earn its place as great. We can argue about that.

Kai Wright: I'm immediately bored.

Bill T. Jones: Really? Are you?

Kai Wright: If you are telling me, what you're doing has nothing to do with you or your life experience. I am immediately skeptical of it. It seems so dishonest.

Bill T. Jones: No. You know, it's a grand tradition, of course. What is a sonnet form? It's a disciplined form that has to do with the length of line, rhythm, image. It's disciplined. There are worse things. How do you feel about a haiku?

Kai Wright: Fair.

Bill T. Jones: Haiku, it's supposed to appeal to the ear first, and then it finds its way through the mind, and it goes to the heart. An old saw, and one that I quote a lot is Marcel Duchamp, who said, art is primarily an intellectual activity. I don't know that I add this, or wherever. You tell your story so many years, you're not sure anymore, but it comes in through the eyes and goes through the mind. Then I say it comes in through the eye, goes through the mind, and if it's really potent, and you and I would agree, it goes to the heart, which is the goal.

Now, can I get right to the heart? I think a lot of Black music does that. I think it's like when you hear someone just say, "Aaah," already, like, "What was that sound?" For me, that's the highest but it doesn't stop there. Art can do whatever it wants to do and that's the scary thing about it. Art should be terrifying, and it should be free in a way that surprises. I have been looking for that. When Arnie died, he and I were very hot in Europe. We were everywhere. Then this slide, this very public slide in his death.

I said to a group of critics at the Cannes Festival, I said that you say these things to the French and they perk up, "I am the surviving member of a celebrated same-sex interracial duet company." A surviving member of a celebrated same-sex interracial. All those levels. That gave me some sort of modus. Arnie has said, "You do not have to keep this company. You're not temperamentally suited to it." He was right. Little did I know.

Kai Wright: You make Still/Here in a context, as you said, of a culture of death. There's so much death happening in the country, in your community at the time.

Bill T. Jones: Just remembering death is always happening. When you're young and you're pretty and you're going to live forever, you think. Anyways, I interrupted.

Kai Wright: You think it's quite distant. Listen. Today it's being remounted, and I was going to ask you to think about it in these contexts versus those contexts. An audience walking into it.

Bill T. Jones: [laughs] I laugh because I just floated the idea with my young company. You know about the piece. We made sure they watched the Moyers documentary, and many of them had studied it or heard about it, and a lot of them did not understand the climate that it was made in. And I asked them, "This is what I was thinking, and this is what's in the piece. Can you hang with me? Are you interested in this? What does it mean to you, as I say to the gay men in the room? Is your sexuality just next door to being a kiss of death?"

Kai Wright: How did they answer that?

Bill T. Jones: They kind of, "Well, we have prep" "What? Oh, prep Oh, I see. Those are drugs you take now before you go out." I said, "In other words, you don't have to worry anymore?" because we were worried. We knew that we were risking every time we had sex with anyone that we were. I don't know if it was-- I had to handle it with a light touch because the company has been through some very intense times, and I think that they were to lean and ask them for anything, and they're young, you run the risk of them feeling somehow they're oppressed, somehow they're being attacked.

Is there a correct answer that Bill wants them to give? I just want to talk to you like my colleagues, but, hey, you're my children. That was one thing. That was one rehearsal for it but they were game. First of all, they loved the idea of performing at BAM. There were people who said, "Oh, gosh, that's my dream to perform the stage at BAM." Hey, never mind my ego about nothing. Doesn't matter what the piece is. You just want to perform there.

Kai Wright: [laughs] At the theatre.

Bill T. Jones: They also trust me, and they definitely trust Janet Wong, my associate director. They want to do something that is-- Now, let me say this. I think they want to do something that's important. They hope it's important. I can't say that everything I've done been important, but I've been striving for it to be engaged in a discussion that's bigger than the beauty of line or how did Martha Graham describe dancers are athletes or acrobats of God. Show me one feed after another on Instagram. The things that you see people doing on Instagram in terms of virtuosity are astounding.

What is that thing called meaning? Then the question is meaning for whom? I had heard in discussions. My producer said, "Are you sure this is the piece you want to, in election year, be opening? Is it?" They said, "No, we think this is the piece that people would want to be giving their attention to." I was saying, "It's so inward, this question of mortality. We have global warming, and we have the war in Gaza. We have protests. We have pollute-- Is this the work that speaks to what people want?" They said,-- and God bless them, and I trust that they're right.

I hope they are, that this is a piece they think that the era will meet it because people want something that this piece was grappling with. Do they want to talk about death? Hmm. I think they want to talk about that place where meaning and beauty and life and death meet. Meaning. I'm a big fan of Hannah Arendt, and she says that the project in Western philosophy has been, "a study for truth." She says that's not really the case. It's not been a study for truth. It's been a study for meaning. Then we're off now.

Kai Wright: Death forces that. To think about mortality does make you think about meaning and your life's meaning.

Bill T. Jones: I think it does. I think you're probably like I am. I'm not sure if it does for everybody.

Kai Wright: That's what makes it so hard to think about, I think for me. To imagine the moment of your death forces me to immediately begin to think about the meaning of my life up until that point.

Bill T. Jones: Bingo. There was a time when Still/Here, we toured so much with that piece back in the day. Someone said, "You should have sat still and take it to an off-Broadway house, and it should have become part of the repertory." Didn't occur to me. We were doing it and then we were not doing it. We were moving on, because that's what we do. Now we're back again with it. The people, our partners at BAM are supporting us. They think that this is really, there is a conversation to be had around it.

Our interview today is very revealing to me. I had announced proudly to my staff, "Look, I will do this at BAM, but I'm not doing any publicity about it."

Kai Wright: Really?

Bill T. Jones: No, no, no. Because I have been in the fire and I know that I will get pulled into it. It becomes about Bill, his HIV, Arnie, AIDS, whatever. I said I don't want to do that.

Kai Wright: Your work has always been so personal. It's so your story. You've put so much of you into everything. It's striking to hear you say you feel like, "I don't want it to have anything to do with me."

Bill T. Jones: It's 30 years old and it's got a sink or swim. I think you get some sense of how raw things were when Arnie died. Then by the time Still/Here came about, and then the response that Still/Here got, which was great, great response but the fight that it started. I don't know, that fight's gone underground now about victim art and people leaning into their victimhood and expecting you, the audience, to come and pay to see them and don't go, that sort of thing. I didn't want to be part of that. I want to be part of the club that has James Baldwin in it, James Joyce in it.

Kai Wright: You are in that club. Dare I say, Bill, you won the argument. I think that’s the point.

Bill T. Jones: That's what Janet says. I hear you. I. How do you feel that we won? I was just talking to her--

Kai Wright: Because no one's having that argument anymore. No one would call it victim art in 2024. That's such a foreign concept.

Bill T. Jones: Well, amen. Amen.

Kai Wright: That's left to the relics because you and your contemporaries won that fight.

Bill T. Jones: So thank you. That means then, Bill, close the drawer on that one. Still/Here will have to sink or swim on its own merits. Are there merits there? Is it pure dance? What is there now in that piece?

Kai Wright: We're always grappling with mortality, right? That's something--

Bill T. Jones: Even works of art, you say. Oh, no, oh you mean--

Kai Wright: As audience members, as people, we're always grappling with mortality, whether we're running from it or not.

Bill T. Jones: I agree. However, since it is so common, the experience, what distinguishes this particular expression from the many others out there? That's the lotto we're playing. Pray for a genius work.

Kai Wright: Bill T. Jones in his living room at peace. He's surrounded by cicadas, a freight train in the distance, and the ticking clock on his wall, Still/Here will be performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music at the end of October. For a link to tickets, go to our episode page. I'd love to hear how you connect your mind and your body. Just call and leave us a message at 844-745-8255. Or you can record a voice memo on your phone and e-mail it to me at notes@wnyc.org. Just be sure to include your first name and where you're calling from, and then share your thoughts on this mind-body business.

Bill T. Jones: Tell us a few stories along the way.

Kai Wright: Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. Follow us wherever you get podcasts.

Bill T. Jones: We'll follow you.

Kai Wright: This episode was produced by Emily Botein. Theme music mixing and sound design by Jared Paul. The music in this episode is the original music from Still/Here.

Bill T. Jones: Where does it start? Where does it go, and try to imagine where it ends.

Kai Wright: Our team also includes Katarina Barton, Regina de Heer, Karen Frillman, Suzanne Gaber, Siona Petros, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. We'd love to have you in our community of listeners on Instagram as well, so find us there at noteswithkai. I'm Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us.

Bill T. Jones: Take us to your death. Right to your death.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.