Novelist Elif Shafak on James Baldwin’s Compassion

[music]

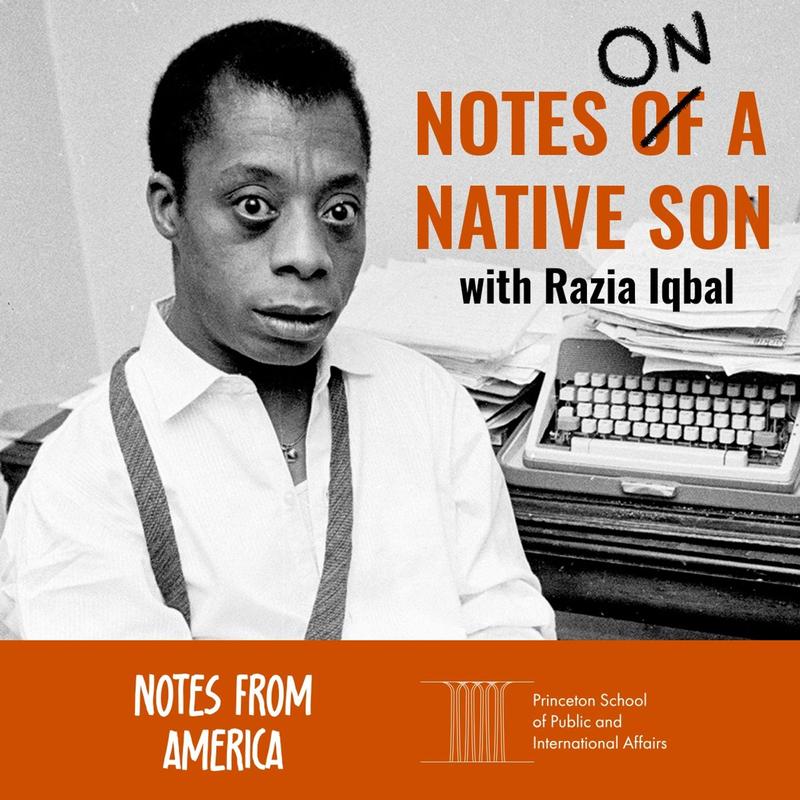

Razia Iqbal: Welcome to episode five of our new podcast, Notes on a Native Son, about James Baldwin, because 2024 marks the 100th birth anniversary of a man unique in American letters. Novelist, essayist, activist, the list is long, though who and what James Baldwin is, as well as his legacy, can't really be listed, but it can, and perhaps should be found in his work. Baldwin himself refused any attempt to box him in.

This podcast tries to get close to the idea of getting to know James Baldwin through his work and those who love his words. We've called it Notes on a Native Son, after one of Baldwin's most famous autobiographical essays, Notes of a Native Son. In each episode, we invite a well-known figure to choose a special or significant James Baldwin passage. The conversation tells us as much about James Baldwin's story as it does about the person who loves Jimmy as he was known to all who loved him.

Our guest on this episode of Notes on a Native Son is the Turkish writer Elif Shafak. She has published 21 books, 13 of them novels, and her work has been translated into 58 languages. She is among those contemporary writers who are both lauded with prizes and deeply beloved by her readers. Born in Strasbourg, France to Turkish parents, her father was a philosopher and her mother a diplomat.

Although her early life was peripatetic, she did live in both Ankara and Istanbul for long periods of time before moving to London. Her deep connection and love for Istanbul connects her to Baldwin, who lived there on and off during the 1960s and early 1970s. They also share a commitment to compassion and empathy in the telling of stories. We spoke to Elif in her home in London.

Elif Shafak: Hi, I'm Elif Shafak, and the James Baldwin quote that I have chosen is, "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive."

Razia Iqbal: Elif Shafak, thank you so much for being part of our podcast. Why did you choose that James Baldwin quote?

Elif Shafak: It really speaks to me. It's very close to my heart. I think it resonates with my own journey, my own childhood. I spent a very lonely childhood, if I may put it in those words. I was raised by a single mom, a working mom. I grew up without seeing my father. I was in a very conservative neighborhood, a very patriarchal neighborhood in Ankara with my grandmother until I was about 10 years old. I thought life was very boring. It was books that taught me there were other worlds, there were other possibilities, I could reach them, that whatever I was going through, that I was not alone. When I read James Baldwin in general, but in particular this court, it really, really resonates with me, in my heart.

Razia Iqbal: When did you first read James Baldwin?

Elif Shafak: I was very young. I was in Istanbul, and I discovered them again and again. Not just once. I discovered his fiction, and then I discovered his essays, and then I discovered that he had lived in Istanbul, and then I went back to his fiction and read everything again. There were multiple discoveries for me.

Razia Iqbal: Of course, he did spend about 10 years of his life in Istanbul, a city that is very close to your heart, but also, in some ways, it seems to me that you going to Istanbul mirrors what Baldwin did too.

Elif Shafak: It does mirror. I think, for me, he's the patron saint of exiles, James Baldwin. That is very crucial for me, because where is home? Can one have more than one home? Where is Homeland? Do we carry our motherlands with us wherever we go? Can we have roots up in the air, not necessarily buried in the ground? Can we have multiple belongings? All these questions that are very, very crucial for me and for my fiction, for my writing. He tackled these questions with immense courage and honesty in 1950s imagine.

At a time when the world was not ready to hear what he had to say about identity, pluralism being multiple inside, refusing to be reduced to a single narrow box of identity, that kind of courage and openness of mind and heart. I think, yes, it does resonate with me, and maybe I find some solace in his work.

Razia Iqbal: It's so interesting to hear you talk about the timing. For him, being in Istanbul felt both critical, but also difficult, as you have alluded to. Critical because he needed to be away from the United States because at that time, he felt that the only thing that might happen to him in the US would be that he would end up in jail. That idea of leaving a place, you could argue running away from a place, but going towards something that is unknown, that's what he did.

In a way, you did that too. You went to Istanbul when you were very young and you didn't know anyone. Baldwin was the same.

Elif Shafak: Indeed. Maybe when I came to the UK also, about 15 years ago now, that was similar in the sense that I really didn't know a single soul in this country. What happens when you move to another land, you might say, when you run away from your own motherland, is that you become nobody. Becoming nobody after thinking that you're somebody, becoming nobody can be quite frightening, but it can also be liberating, that kind of freedom.

When I read his memoirs, his journeys, both in Istanbul but also in Paris, I think that's the one thing that he experienced immediately, becoming nobody or that kind of freedom of no one knows now who he is, his family. It's quite frightening for an author, leaving your culture behind, leaving your habits behind. At the same time, when I look at America at the time, what he had to deal with, the kind of homophobia, the kind of racism, all those barriers of discrimination, but not only that inward-looking communities, that perhaps do not respect his individuality. All of that, I think I can understand. I think I can relate.

In many ways. I think America broke James Baldwin's heart. In many ways, Turkey broke my heart. I know how it feels like to go somewhere else to try to find your feet again, find your voice almost from scratch. We call it self-imposed exile, but can exile really be self-imposed? It's a tricky question. It's internal and external at the same time.

Razia Iqbal: There are push and pull factors, right?

Elif Shafak: Push and pull factors both.

Razia Iqbal: You strike me as someone who might have been able to choose any number of quotes from Baldwin's work. The one that you chose came up in a magazine interview in Life magazine in 1963, I think. Right after the quote that you have chosen, he talks about what it means to him to be an artist. He says, "An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell because nobody else in the world can tell what it is like to be alive. I'm not trying to solve anybody's problems, not even my own. I'm just trying to outline what the problem is." I suspect that given what you've just said, that also resonates with you.

Elif Shafak: I love that. I love every word in what you've read. I think there are multiple layers that primarily, for me, literature is not only about stories chasing words. Of course, as storytellers, we love stories, but I think we're equally drawn to silence. That is very powerful in James Baldwin's work, to look at the periphery rather than the center. He wants to know who are the silence, where are the silences in the society in that particular moment in time. I like that so much.

He also talks very bravely and openly about the integrity of the artist. He talks about it as a struggle. It's not something you can achieve in one day and then put it in your pocket and take it for granted. You have to work on it every day. It's so difficult to maintain that integrity. I think he's incredibly honest. He's not trying to be a hero. There are no heroes in his books. There are real people with conflicts, contradictions, elements of good and bad struggles. How do we maintain the dignity, equality, a better future? You have to believe in hope. There's a moment when he says, you know, I have a nephew, "I have a niece. I cannot afford despair. I can be angry, I can criticize, I can even feel sad sometimes, but I cannot afford despair. How to have hope and how to give hope to others, these are not easy things. He's incredibly honest about all of them.

Razia Iqbal: When he was in Turkey, and I'd love to hear a bit more about your own reflections of your sense of history of Turkey at that time, or Istanbul. By the time he got himself established there, he used to host parties. He had lots of very famous friends. He finished at least four or five of his books in Istanbul, going back and forth and so on.

There were also real tensions, right? He was seen as the Arab Jimmy. The Arab Jimmy because there weren't so many African Americans in Istanbul at the time, not surprisingly. Also, there were real issues with his homosexuality in that culture.

Elif Shafak: Of course. Absolutely. Indeed. Earlier we talked about how he found freedom when he moved from America to both Paris and Istanbul. Of course, when you dig deeper, his life in Istanbul, on the one hand, it might look like not only parties, but he was welcome, definitely. He maybe has thrived in that literary and cultural circle, particularly in Istanbul. I can see that. I can also see, when you look at his pictures, the pictures of him taken in Istanbul, there is a melancholy. There is a solitude. There is a loneliness there that is very, very clear.

Then when you start digging deeper, and in Turkey at the time and still is, I wish I could tell you that we have made tremendous progress since then, and we're not as homophobic or as patriarchal as we used to be, but that's not the case at all. It is still a very homophobic society, very misogynistic, and when it comes to race, this is a big subject in Turkey that we find difficult to talk about because we like to think that racism is a problem of America, of Westerners, that we had never that kind of problem. That is nonsense. It is a racist culture in that sense. How did he experience that? There are some really, really hurtful anecdotes where he's chased or called names.

Razia Iqbal: Actually beaten up in one instance.

Elif Shafak: Beaten up, yes. Both physical and verbal violence he has experienced in Istanbul for being Black, for being gay, for just looking, 'slightly different. These are, of course, very painful memories.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: It seems to me that the way you speak about Baldwin, and you certainly have written this, that he acts almost as a talisman for you in your own writing, but also in the reality of your journey and your life. We're sitting in your home in London and there is a James Baldwin candle in your study. Tell us about that.

[laughter]

Elif Shafak: I'm very, very fond of this candle. I found it in a small shop in America and I carried it with me, actually. I was so afraid that it would break if I put it in a suitcase.

Razia Iqbal: It's interesting because it's not-- I just want to describe it because it's about the size of maybe a pencil and a half. It's got a picture of Baldwin on it, which he's looking very dapper, very dapper indeed. He's carrying a book and wearing a cravat and it just says James Baldwin on it. Why did you carry it around with you? Where did you find it? Do you remember?

Elif Shafak: It's a random small shop. I just walked in and I saw this on the shelf. It was like, yes, miracle.

[laughter]

Elif Shafak: Universe telling me something. The rest was funny because, I was really, really scared of breaking it and I had to carry it in my hand and it came with me. It crossed the Atlantic with me. I brought it to London. When I write, I like to have it next to me.

Razia Iqbal: There is a halo of fire around Baldwin's head, which I think is quite interesting. What do you think that means?

Elif Shafak: Well, there is fire in his work, isn't there? Both in his essays and in his fiction. I think it's a fire that has grown as he aged, but that doesn't mean aggressiveness in any way. It is a strangely calm and wise fire, but the fire was always there. I think it was Toni Morrison who said, "When I look up the world, I feel so angry sometimes." If you care about what's going on in the world, you do feel that rage, but then Toni Morrison says, "On days like that, I go, I sit down at my desk and I write."

I love that because it's okay to feel sad or angry or sometimes even depressed. That's precisely what he did. There's so much, understandably rage and hurt pain, immense pain in him, in his writing but then he takes it, he sees it as a source of energy and he turns it into something incredibly radical and transformative.

[music]

Razia Iqbal: We'll take a short break. More from Elif Shafak when we come back. This is Notes on a Native Son with me, Razia Iqbal. You're listening to Notes on a Native Son with Razia Iqbal. I wonder what you make about Baldwin's reputation today. You are somebody who is very active on social media. You have a lot of followers, more than a million. Tell us how many people follow you on Twitter and Instagram.

Elif Shafak: To be honest, I have left Twitter. Look, here we are still calling it Twitter.

Razia Iqbal: Yes, exactly.

Elif Shafak: Indeed, a while back, because I think it's becoming more and more toxic. The reason why I cared about social media, primary reason, was coming from a country like Turkey, where you see the press freedoms shrink, and also that the public space not necessarily being equal to all minorities, youth, women in particular, the digital space mattered for us. I just couldn't brush it off.

Razia Iqbal: The reason I asked about social media is that Baldwin still has a place in 21st-century life in that context. He is, very often there are little clips of his interviews, little memes. People will, James Baldwin t-shirts with all kinds of things written on them that he has said. He still is a writer that people turn to. I wonder what you make of that, because, of course, every writer wants to have a legacy. This tiny bit of Baldwin's legacy is manifest on social media. He obviously is a much bigger figure otherwise we wouldn't be doing this. We wouldn't be having this conversation if we didn't believe that. I wonder what you make of that. His presence can continues in this new sphere.

Elif Shafak: I love that. I don't necessarily see that as something sinister or capitalism-consuming names. I don't necessarily see it that way because most of what you're saying is coming from young people. They're making these videos, they're wearing these t-shirts. They're discovering James Baldwin because it speaks to them. His writing speaks to them.

That's the beauty of James Baldwin's legacy. On the one hand, of course, he's the son of a particular era and a certain country and culture, on the other hand, it's so timeless and placeless and universal and urgent. Everything he says, I think it's very relevant in today's world. You can't necessarily put him in a certain century or a bygone era. That's his power. That's his magic.

Razia Iqbal: I wonder what you make of the idea of him being this kind of international intellectual both then and now, given that he did not confine himself only to the United States, even if he needed to leave the United States, either to go to Paris or-- he traveled all over the world. He went to Algeria, he went to Senegal, he lived in the south of France by the end of his life. This was a person who consumed the world in some ways. What do you think that tells us about the kind of public intellectual he became?

Elif Shafak: He uses the word commuter. He commutes between cultures and countries. I love that. I love that word. He's a nomad. He's an, of course, exile. I'm so glad you used the word intellectual or emphasized the word intellectual. It always amazes me on both sides of the Atlantic, both in the UK and US, the word intellectual is used in such a negative way, as if intellectual means, heirs and graces. Someone is being arrogant, and that's not necessarily what intellectual is. There can be another meaning, and I think it is important to have public intellectuals.

Ironically, when I look at other countries like France, of course, there's a very different tradition of public intellectuals, although it's quite male-dominated. When I look at countries like Turkey, paradoxically, we attack, target, persecute, prosecute, even imprison or exile our intellectuals, but in a strange way, we also recognize that they matter, that they exist.

My approach is, I think we need public intellectuals, and what we need is more female public intellectuals. That side of James Baldwin, he didn't try to be a public intellectual. He didn't claim to be one, but that's who he was with his words, not only with the written word, but also with the spoken word, he made a difference. The spoken word is also important. If you can merge these two worlds or bring the world of oral storytelling with written storytelling, that's a good thing. That can be a very radical thing.

Razia Iqbal: It's interesting hearing you talk about the kind of persecution and sometimes prosecution of public intellectuals in Turkey and in many other countries. Part of the reason why we know that that happens is because there is fear in those people being free to say what they want to say. Part of the reason why whenever people say to me, "Oh, nobody reads anymore," and, "Books aren't important," etcetera, I always want to say to them, "You do know that books are banned in the United States, this country that professes to be free and open, etcetera, etcetera." You only ban things if you're frightened of them.

Elif Shafak: That is so, so true. I think, again, countries like Turkey show us that history is not linear. Tomorrow is not necessarily going to be more, progressive than yesterday, that countries can go backwards. When that happens, when democracy starts to crumble, I think the very first rights that will be curtailed will be women's rights, LGBTQ rights, and minority rights in general.

Coming back to books, there's this assumption that books can be dangerous. Why? Because, as you said, it's associated with fear. This is something I've experienced a lot in Turkey. I was put on trial for writing a novel called The Bastard of Istanbul, which talks about an Armenian American family and a Turkish family, and it talks about one of our biggest taboos, if not the biggest taboo in Turkey, which is the Armenian genocide.

The moment you talk about this in literature, because there's a huge silence across Turkish literature about the Armenian genocide, which is very, very interesting, then you're immediately labeled as betrayer or traitor. I wish I could say it was only then, now is better. It's not any better now. I've been also prosecuted for writing about sexuality, gender, accused of so-called crime of obscenity, accused of insulting Turkishness, and so on.

The reason why I'm sharing this, I try not to forget the other side, which is that books matter, that stories matter. Interestingly, in countries such as my motherland, a book is never a personal item. If a reader likes a book, they don't just put it back on the shelf. They give it to their neighbor, and the neighbor sends it to her aunt, and the aunt sends it to her son, who is maybe doing his compulsory military service.

I have seen so many copies of my books underlined by different colored pens because different people have read. On average, five to six people read the same copy, and there's that kind of word of mouth, that kind of sharing. This is why books still survive and thrive even in this age of lack of freedom of speech and all kinds of attacks against libraries and books.

Razia Iqbal: I think Baldwin would have loved that-

Elif Shafak: He would have.

Razia Iqbal: -idea very much. I wonder also about what he would have made of that very first prosecution that you faced, which was about the words of a character in a novel. The absurdity and surrealness of that in and of itself, I think, would have appealed to his mischievousness.

Elif Shafak: True, indeed. Indeed, because it's so surreal. When I was accused of insulting Turkishness under Article 301 in the Turkish constitution, which protects Turkishness against insults, even though nobody knows what that means, it's very open to all kinds of interpretation and misinterpretation. This article had been used against journalists, historians in the past, but never before against a fiction writer.

I found myself in this really Kafkaesque, I can only say, situation when the words of fictional characters were taken out of the book and used as evidence in the courtroom, as a result of which, my Turkish lawyer had to defend my Armenian fictional characters along with me. That madness went on for over a year, during which time there were groups on the streets, ultra-nationalists spitting at my pictures, burning EU flags, and then we were acquitted a year later, me and the fictional characters. I had to live with a bodyguard for a year and a half.

The whole experience, on the one hand, is quite upsetting, unsettling, but there is a strange humor, or surreal humor in it as well. "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read, it was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive."

Razia Iqbal: There are many people that we are speaking to in this podcast who knew Baldwin. You didn't, but you do know him through his work. If you were in a room with him, how do you think that conversation would go? Because, you know, it's trying to get that balance right between not being a fan girl.

[laughter]

Elif Shafak: I can't promise. Every now and then, they ask us in interviews, what would be your dream dinner? Usually, it's Virginia Woolf or James Baldwin. For me, they would definitely be my dream dinner guests. I would have loved to listen to him. His voice, I love the way he speaks. He's someone who almost savors tastes, every word before he utters those words.

You can see that this is someone who's aware of the power of words, of the magic of words, that he doesn't speak them lightly, he doesn't take them lightly. At the same time, as you said, there's mischief, there's lightness, there's joy. That oxygen. Humour is our oxygen, so there's that in him as well. I think he would be an amazing person to have dinner with and then go out and party.

Razia Iqbal: Well, given that you and Baldwin have both been commuters in the world, where do you think that dream dinner party might take place?

Elif Shafak: What a beautiful question. I think we would have that dreamed on a houseboat. It could be any river in the world. It could be the Thames, of course, but it could be the Seine or another river.

Razia Iqbal: The Bosphorus.

Elif Shafak: The Bosphorus. Yes, but definitely a housebat.

Razia Iqbal: I'm not sure that Virginia Woolf would want to be president. Maybe Baldwin or Virginia. [laughs]

Elif Shafak: This is my dinner with James Baldwin.

[laughter]

Elif Shafak: This is my romantic dinner with him.

Razia Iqbal: Elif Shafak, it's been a pleasure speaking to you. Thank you so much.

Elif Shafak: It's been a pleasure for me. Thank you.

Razia Iqbal: This has been Notes on a Native Son. That was Elif Shafak speaking to me, Razia Iqbal. In the next episode, we'll hear from the writer Caryl Phillips. Born in the Caribbean, he grew up in the UK and now lives in the United States. He is among the people in this podcast who knew James Baldwin and counted him as a friend and mentor, in Caz's case, towards the end of Jimmy's life.

This podcast is brought to you by WNYC Studios and sponsored by the School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University. It is a Sea Salt and Mango production produced by Tony Phillips. The researcher is Navani Rachumallu, the executive producer for WNYC Studios, Lindsay Foster Thomas. Karen Frillmann is our editor. Original music is by Gary Washington. The sound designer and engineer is Axel Kacoutié. Special thanks to Dean Amani Jamal of Princeton University.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.