James Baldwin's Words Continue to Challenge us 100 Years After His Birth

Kai Wright: Hey, it's Kai. I am jumping into the feed here to give you something super special and well-timed. 100 years ago this weekend in 1924, August of 1924, a baby was born in Harlem Hospital. His name was James Baldwin, and of course, he would go on to become one of the most influential writers and thinkers, and activists of the 20th century. Really one of the most influential person of letters in American history. His ideas and his words just shaped generation after generation of people, queer people, Black people, writers, activists, you name it.

There's a new podcast coming that really explores this idea, this lineage, this inheritance that James Baldwin has passed down. It's called Notes on a Native Son, which is, of course, a play on James Baldwin's first essay collection "Notes of a Native Son." It's hosted by Razia Iqbal, who is a professor in the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. She joined me in the studio a few days before James Baldwin's official 100th birthday to talk about this podcast, Notes on a Native Son. Here's our conversation. Here's me and Razia Iqbal.

Razia Iqbal: Notes on a Native Son. This was an idea conjured up by an old friend of mine who is also the executive producer on the podcast, Tony Phillips, who used to work at WNYC. An old, old friend of mine.

Kai Wright: Shout out to Tony.

Razia Iqbal: Exactly. Always. His idea was to try and get a handle on Baldwin's words, to focus on his words. How would we do that? Because he is a ubiquitous figure for so many people, memes, t-shirts, tea towels, posters, mugs, whatever. How do we go back to try and really find a way of talking about his writing? He came up with this idea of inviting people who have a relationship with Baldwin, have, like you, been interested in his work and get them to choose one passage and riff on that.

Kai Wright: Riff on that. Razia, I imagine everybody listening right now is like, "Wait, that's Razia Iqbal from the BBC." Why is she talking about James Baldwin? Tell us about your relationship to Baldwin.

Razia Iqbal: It is Razia Iqbal, but formerly of the BBC. I now teach at Princeton University, and Princeton have sponsored this podcast, which is a real joy for me. My relationship to Baldwin goes back to when I was a teenager growing up in south London. I was born in East Africa but moved to London when I was eight. I started reading Baldwin, I guess when I was probably about 15 or so. You might ask yourself, Muslim girl, a teenager growing up in south London in the 1970s, what on earth would Baldwin be saying to me?

This is what I love about him as a writer. He gave me a language to think about power, to think about the structure of power, but he also gave me something that I have carried with me and feels like a true gift, which is the ability to appreciate the most beautiful prose. His essays are peerless, but his novels are also just full of compassion and sentences that are just extraordinary. I think one of the things that I find so interesting about him is that the cumulative impact of one amazing sentence after another, stays with you. It has this kind of ability to become porous, and it becomes part of you. As you were saying, he towered over your life.

Kai Wright: They're epic. The sentences are just epic. They could go on for pages, and it's almost like you enter a trance. The thing he's getting at, it just starts to burrow into you and you can't shake it, and it's similar to audio, I think, in that way.

Razia Iqbal: Yes, there's an intimacy.

Kai Wright: There's an intimacy that just gets at you in a way that you don't normally get at with words on a page.

Razia Iqbal: You feel like Baldwin's talking to you and only you, and I think that is quite an extraordinary gift for a writer to have. It's possible that he never really felt he had it because his need to write was so profound, but I think what he meant to me was that he gave me a language to think about what it means to be other and othered in a society that didn't, at that point, really have that many people that I could turn to. I was very lucky, in fact, with Tony, we saw him in one of his final appearances in public in London.

It's a small moment, but it feels like a really big, rich moment. Just to occupy the same space, the same room, as somebody who is a giant in intellectual and literary terms, and, of course, anyone who knows anything about Baldwin knows that he was this diminutive figure. He was a small man.

Kai Wright: Right. This tiny man with this massive personality and voice.

Razia Iqbal: Exactly, and I think one of the things that I will remember from that day. If I take you back to a moment in mid-1980s in London when public places were places where you could smoke inside. It just wouldn't happen now. This room, it was, I think in the National Film Theatre the smoke just hung. Jimmy was a smoker. It just hung in the air and it was packed, obviously, because it's James Baldwin. What I remember, not just that atmosphere and just being riveted by his words.

A young man stood up and asked a question, a young American man sitting not very far from us, and he said, Mr.-- I'm not even going to try an American accent. "Mr. Baldwin, what advice would you give to a young man starting out to write?" Baldwin took this big drag from his cigarette and he said, "Young man, read. Just read," and you know that actually, in order to be the writer that James Baldwin became, he had been the most magnificently committed reader. His deep intelligence comes from that, too, right?

Kai Wright: Well, speaking of his words and reading, like you said, part of the premise of the podcast is you ask people to give you a James Baldwin quote, and then you go from there. We have asked you to come with your own James Baldwin quote or passage, and you have come prepared. What do you have for us?

Razia Iqbal: I have chosen something from Notes of a Native Son, which was an astonishing essay, the eponymous essay in that collection, and it's really right at the end. For those who don't know the essay, just very briefly, it's an essay in which he reflects on four things that have happened on the same day. August the 1st, August the 2nd, and appropriately obviously, the centennial of Baldwin is coming up, and that's why I chose it. This essay looks at four things that happened on that day.

James Baldwin turned 19, his father died, his father's youngest child was born on that day, the 9th child in the Baldwin family, and there was a riot outside the church where his father was being buried. Through these four things that happen in the essay, Baldwin reflects on for me, the things that are really important about him. He reflects on the personal as well as the political, with a small p. He's talking about what it means to be African-American, what it means to be American, what it means to be what's the soul of America really about.

That's really what this essay is ultimately about. It's also about his personal hatred towards his father, and hatred is an important thing. This is the passage that I have chosen. Hatred which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated. This was an immutable law. It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancour of life as it is and men as they are.

In the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace but this did not mean that one could be complacent for the second idea was of equal power, that one must never in one's own life accept these injustices as commonplace, but must fight them with all one's strength. This fight begins, however, in the heart, and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair.

Kai Wright: One of the things that I love so much about Baldwin that you just got to was the way he weaved the individual personal intimate struggle with the system struggle. As somebody, myself, who spent a lot of time in racial justice spaces thinking about the politics of racial justice, it's always these things are intention. You want to tell people, "Oh, think about the systems, think about the way there's these big ideas that shape our lives, not about individuals which is an alienating thing, I think, to tell people, to tell an individual and Baldwin is so profound in his ability to think about his own biography and his own way that he is moving through the world. Put that inside these big ideas and these systems. I think that's part of what makes him so sticky for me.

Razia Iqbal: What do you mean sticky? That's interesting.

Kai Wright: That we're 100 years into this conversation with James Baldwin, that this is an essay collection from 19, what? 55, right?

Razia Iqbal: Yes.

Kai Wright: It's 2024, it feels present tense. It feels relevant right now. We can't shake him, and that's a good thing. We shouldn't shake him but there is, I think it's something about what I hear in that passage, this personal and analytical at once.

Razia Iqbal: That's so true but it's also the thing that I think he does that makes Baldwin travel all over the world. In a way, we try to get at this in the podcast because there is a universality about Baldwin that I think people underestimate. He was a man who traveled a lot. His view of the United States changed profoundly when he felt he had this existential threat against him. He had to leave which is when he went to Paris. He traveled to West Africa, he lived in Istanbul and we have on our podcast Elif Shafak, the Turkish novelist talking about him and how he's this talisman for her.

We have Siri Hustvedt talking about the philosophy underpinning his impact on her and how she sees him as this quintessential American figure. Given that the thing he grappled with was this idea of what it means to be American. This essay, in particular, he's thinking back on a time in 1943, America's in the middle of this war. What's the war for? Freedom. It's against fascism. It's against the yellow peril.

It's not lost on Baldwin that African Americans are being conscripted into this army where they are being asked to kill in the name of freedom but the riot about which he speaks is very specifically about the story and the rumor that went around at the time that a white police officer had shot a Black soldier. Even if the truth of that story wasn't true necessarily by the time that everyone found out the facts that he'd been shot in the back but think about that narrative and how it is continuing to hit us almost on six-monthly basis. We see state power against African Americans being wielded again and again and so that's what makes Baldwin relevant time and again.

Kai Wright: Finally, we'll be talking about it on our show this Sunday. You mentioned Elif Shafak. We have a cut from that conversation. Let's hear a little bit of that.

Elif Shafak: When you read Audre Lorde, when you read James Baldwin together, what they are saying is they're saying, "Look at me. I'm Black. I'm a poet. I'm gay. I'm perhaps a mother or an uncle. I'm this, I'm that and I'm many more things that you might not be able to see at first glance." I contain all those multitudes. Like Walt Whitman used to say, "This is something that worries me. Perhaps in today's progressive movements, we have forgotten that emphasis on multitudes to be able to say, I contain multitudes."

Kai Wright: That was Elif Shafak talking to you about that relationship to James Baldwin when-- You talked a little bit about it but respond to that cut there, what were you guys discussing?

Razia Iqbal: We were talking about something that Elif has been concerned with for a very long time which is this idea of the multiplicity of stories and she quotes Walt Whitman who, of course, is the American poet that people will turn to when they're talking about the idea of the polyphony of voices that we want to have in our culture and in our society. Elif is so concerned that the polarization that we live in, in society today, particularly in the United States but in most Western developed countries, that somehow that is reducing the possibility of who is going to be heard.

That really concerns her. Baldwin, of course, was deeply concerned with that. Part of his, if indeed he felt he had a mission, he certainly felt he had a responsibility to engage with those ideas of who's heard and who's given a platform and who isn't even though he never really wanted to be a spokesperson, he was aware. He was telling stories that were not being heard at a time when they were being diminished and marginalized and so that was what was really of interest to her.

Kai Wright: He was telling these incredibly challenging stories as well. They're challenging today, let alone at the time that they were written for many of them. Let's take a break, and when we come back, we'll hear more selections from your podcast Notes on a Native Son.

[music]

Kai Wright: It is Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright. I am with Razia Iqbal, Princeton University professor of journalism and former BBC host who has a new podcast called Notes on a Native Son, all about James Baldwin. Razia, let's hear another bit of the podcast. Here's somebody else you spoke to Ta-Nehisi Coates, who to many people is a James Baldwin of today at least for part of his work. Let's hear a little bit of what he said to you and then we'll talk about your conversation with him. Here's Ta-Nehisi Coates.

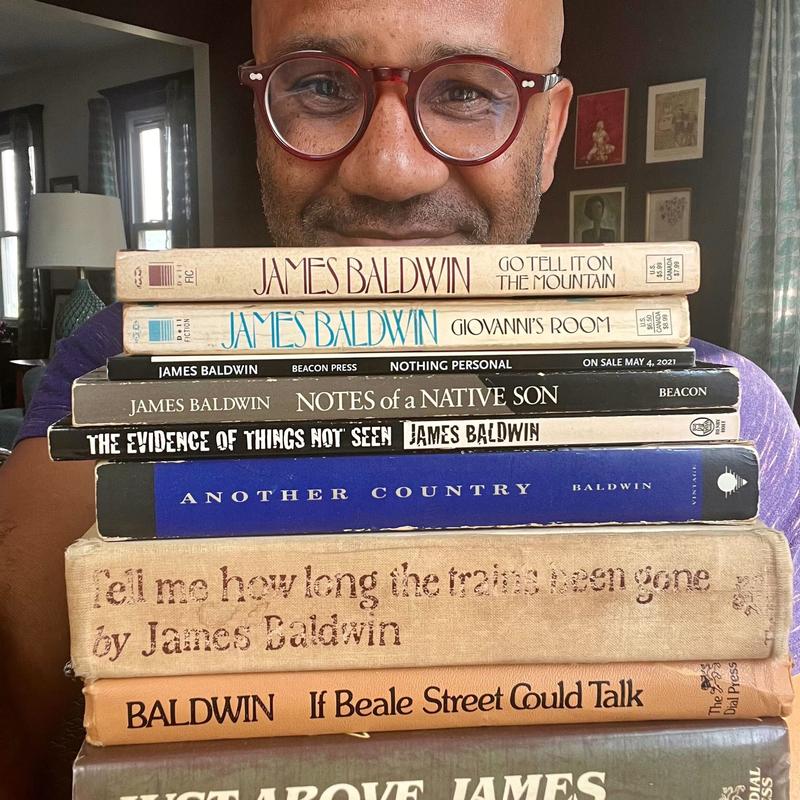

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Baldwin has become such a huge figure because the idea of him has become so huge because he is on posters because there's art about him, because they're clip shared about him. It is really easy to miss the fact that he was one of the greatest, I say, of the 20th century. You know what I mean? He was, and maybe the greatest. He was a phenomenal writer and the image obscures that.

Kai Wright: Razia, that really resonates with me. This idea of Baldwin like many figures of the past has just become a slogan or almost a visual slogan when he contains, it's just so much complexity. Is part of the project here, bringing back that complexity, I guess?

Razia Iqbal: I'm not sure that I think the complexity is lost but I do think that because anyone who reads Baldwin will see the complexity on the page. In some ways, of course, the podcast is designed to walk people back to the work. To invite them to engage, not just with hearing what illustrious people think about him but to really go back to the words, and Ta-Nehisi talked about the words the entire time we were in conversation.

He talked also about his own struggle to try and get those sentences correct and right, and why that was important to try and find a new language to talk about old problems that still exist. He grapples with this constantly. Baldwin is a talisman for him. He continues to be somebody who he reaches for in terms of the quote that he chose. When I read that quote, he said, "Of course, I know that's what I'm aiming for and so I have to keep working harder because I'm not there."

He's more than a talisman for Ta-Nehisi. It seems to me that he's somebody who carries a responsibility almost because Toni Morrison famously said of him that she worried when Baldwin passed that there would be no one to take his place to occupy his place and then she worried less because she read Ta-Nehisi Coates. That's of course a wonderful thing for Ta-Nehisi Coates to have and to carry but it also requires a responsibility to do with it something new because nobody-- there is only one James Baldwin.

We know his uniqueness because these conversations I've had with people indicate that people from all over the world, different kinds of writers, different kinds of thinkers have engaged with him and that feels so exciting to have rediscovered that because you and I, we've been reading Baldwin for years. You think you are on your own in this little library corral and you're just reading Baldwin or in your home or whatever.

I suppose part of the podcast is designed to show people that his work continues to have resonance and continues to be a place where we should all go, both for comfort, consolation, and actually some guidance for resistance if you like. There is something about the way in which Baldwin uses language that it gives you a way of talking about resistance.

Kai Wright: Again, both personal and political. My real introduction to James Baldwin. I have been reading him since I was a kid but the first time I really read him in the way that you're describing was when I came out as gay to my father in a letter. He wrote a letter back where he encouraged me to go read James Baldwin.

Razia Iqbal: That's extraordinary.

Kai Wright: I think he specifically said go read Just Above My Head if I remember that correctly. I started to dive into Baldwin in a whole new way to understand me and understand how to live. In his message, the point in the letter was, "Well, what I have raised you to do is to lead a truthful life. You must be true." Here's a man who knows truth.

Razia Iqbal: Your father sounds astonishing.

Kai Wright: He had his highs and his lows like all humans but this was a high moment for him.

Razia Iqbal: [unintelligible 00:21:11] what a great story? That's the thing I suppose that Baldwin is to so many people. As Elif was saying, the LQBTQ+ community will embrace him. Young African Americans will embrace him but I sometimes think that these kind of silos are exactly the thing that Baldwin wasn't interested in. For him, this passage that I chose, the fact that he feels he has to work to put hatred and despair to one side, so much about Baldwin is to do with love. So much of his writing, both essays and novels, is really to do with our capacity to love, our limitations.

Kai Wright: The struggle to love, the political act of loving, and how hard it can be.

Razia Iqbal: Exactly. I think in that way, for me, he is as universal a figure as any writer that is held up as the great American novelist, the great American whatever. These labels are just, in some ways, completely reductive and ridiculous because there is no such thing as the best when it comes to the pursuit of art. I think one of the things that Baldwin gives us is the potential for personal transformation as well as political transformation in whichever little group of people, whatever tribe we choose to belong to. He gives us the way in to see the world in a bigger way.

Kai Wright: Let's hear one more person from the podcast. You spoke with Bryan Stevenson who is, of course, a towering figure today himself he runs the Equal Justice Initiative and has done so much to change our narratives on the history of racial violence. Here's what he said to you about James Baldwin.

Bryan Stevenson: I think one of the great things about Baldwin is that he was a courageous writer. I think he's given me and a lot of other people the courage to be honest about what we do and the nature of our struggle and the nature of our journey. I've spent my whole life standing next to the condemned, the imprisoned, the marginalized. There's a lot of contempt, there's a lot of resentment, there's a lot of hostility when you advocate for people who are disfavored people, who are hated, people who have been vilified, people who have been reduced to their worst act.

Even if you kill someone, you're not just a killer, you are more than your worst act. I think that idea comes through Baldwin's writings as well. He was compassionate.

Razia Iqbal: Bryan Stevenson, wow, what to say about this man? Everything he said in that little excerpt we heard. He is getting to the heart of not just Baldwin but himself. He's also telling us something about the generosity of spirit that is required to do the work that he does, and he recognizes that in Baldwin. He recognizes this idea that to reduce somebody to the one terrible thing that they did, even though society defines the murder of another human being as the most heinous act.

Here is Stevenson saying, "What I learned from Baldwin is the courage to stand next to these people and engage in their lives. What a gift for a writer to give somebody who is an astonishing civil rights lawyer, an astonishing human being." For me, these conversations have revealed to me how extraordinary the individuals we've spoken to as well as revisiting how extraordinary Baldwin was. It moves me beyond anything really to listen to Stevenson because there really is in him a capaciousness, this generosity of spirits.

Kai Wright: Talk about the capacity to love.

Razia Iqbal: Exactly. We wrote to people saying, "Please, choose one favorite passage." In fact, one writer chose not a passage or a favorite quote but chose an interview that Baldwin had done in the '60s on The Dick Cavett Show, and [unintelligible 00:25:27] chose that. It was so interesting. I thought Stevenson would say no when we asked him. Not only did he write back straight away-- He's such a busy man. He wrote back straight away and he said, I've chosen three Baldwin quotes and we were like, "Okay, we're going to go with that. This is amazing."

Kai Wright: Did anything shift for you in the course of making this with your relationship to Baldwin? Is there something for you that changed how you feel about him or think about him that you learned from these conversations?

Razia Iqbal: I learned one thing about the willingness of people to, first of all, give of themselves but I think which Baldwin engenders in one anyway. It also led me to feel, kind of sounds hokey, doesn't it? To say that one feels privileged but we did speak to people who knew Baldwin. I think that closeness to somebody who you have admired and has actually been someone you have been in this long conversation within your head and on the page, that is quite something to be able to really be in conversation with--

For example, we spoke to his biographer, David Leeming, who knew him for decades. Baldwin used to refer to Leeming as, "Oh, you're my Boswell." Perhaps Leeming would be the person that would write his story. In the end, I think one of the things that the conversation with Leeming made me feel was, actually, Baldwin has written his own biography through his work. This podcast is opening of a door that allows people to see and engage with Baldwin's own sense of himself, and that has been really special. I've not really thought about Baldwin in quite that way before.

Kai Wright: The podcast is called Notes on a Native Son. You'll start hearing it right here in your feed in September. Razia, thank you so much for this time and for doing this podcast. I cannot wait to hear it.

Razia Iqbal: Thank you so much, Kai. It's been an absolute privilege. Thank you.

[music]

[00:27:57] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.