How Black People Built American Democracy: A Juneteenth Celebration

[MUSIC - Notes from America: Theme music]

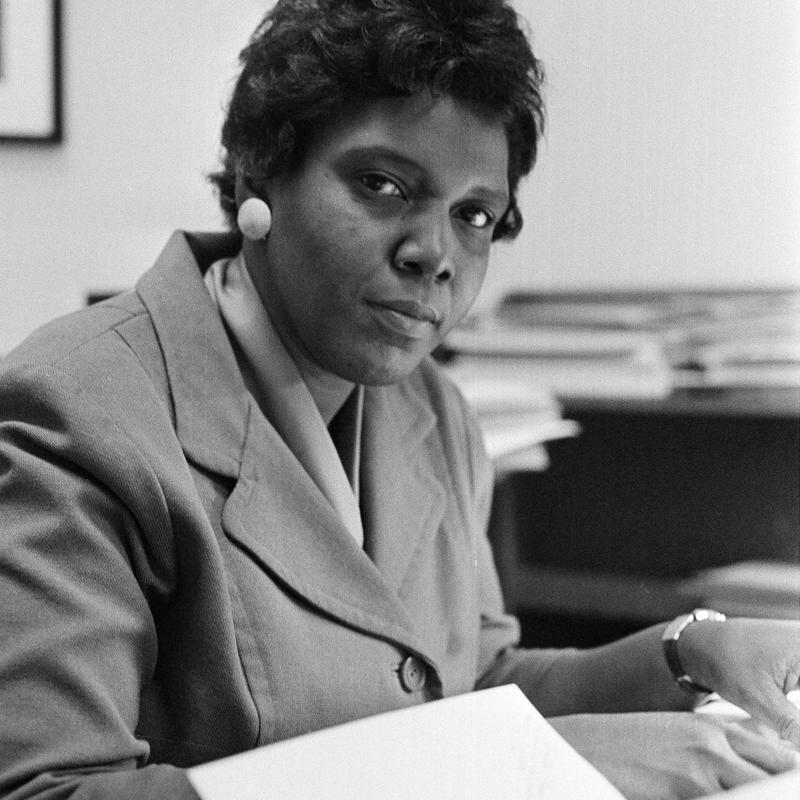

Kai Wright: We're out on the streets of Houston asking people, "Have you ever heard of Barbara Jordan?"

Participant: Actually, I don't know who Barbara is.

Participant: I don't know either.

Participant: Is she in the news or something?

Participant: No.

Participant: No.

Participant: I've heard, but I can't recollect right now.

Participant: Yes, I think so. Barbara Jordan? No. I'm mixing her up with another Barbara.

Participant: They got schools and stuff named after her.

Participant: I do know Barbara Jordan. She was elected to Congress.

Participant: Barbara Jordan, one of our first African-American women members of Congress, she represented the area that I grew up in and I've seen so many film clips of her thunderous voice doing some important work on behalf of the people of not only the 18th District, but for the entire nation.

[MUSIC - Notes from America: Theme music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and welcome to our annual Juneteenth special. We are coming to you this year from Houston, Texas, where we are recording live at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church.

[applause]

This 152-year-old congregation has seen a lot of history. From the moment of emancipation forward, it's been witness to how Black Americans have pushed the United States to make the words in our Constitution real. Throughout our national history, members of this congregation have been trailblazers on America's journey toward true democracy. We're going to learn about one of those members in particular, the late Congresswoman Barbara Jordan.

Now, as you just heard at the opening of the show, Barbara Jordan's name may not ring a bell for a lot of people today, particularly younger people, even here in Houston. Barbara Jordan, who died in 1996, was a pivotal figure at a pivotal time in our national history. Among many other things, she was the first Black woman elected to represent a southern state in Congress, that was 1973. I want to put this in context, because you've got to understand something. When the Civil War ended and the period known as Reconstruction began, Black people rushed into government, briefly, until Jim Crow took over.

More Black people served in Congress in those years right after the war than in the whole next 100 years combined, until the Voting Rights Act reopened the doors and Barbara Jordan was standing there ready. She was one of the people who created multiracial government following the Civil Rights Movement. She went on to play a crucial role in forcing Richard Nixon's resignation following the Watergate scandal and became known as one of the greatest orators in the history of American politics with her passionate defense of the US Constitution. It all started for her right here at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in her hometown of Houston, Texas.

To begin, I'm joined by Barbara Jordan's biographer, Mary Ellen Curtin, and by Reverend Ronald Bell, who is the senior director of membership at Good Hope and a lifelong member himself. Welcome, both of you, to Notes from America. Reverend Bell, let us start with you because you can help us meet the late Congresswoman when you were in college. You had the opportunity to interview her for an assignment and since we cannot interview her ourselves now, we're going to try to live vicariously through you for a moment. Set the scene for us. When did this happen? What year was this and what was your occasion for interviewing the Congresswoman?

Reverend Bell: It was around '89, '90, and I was taking a political science class at school and college and I was writing a paper on the statehood of Washington, DC. I was a proponent and I needed an opposing view. I looked right to her sister here at church, who I knew well and knew me growing up, and I asked her to help me get an interview. She was then a professor at the LBJ's Public School Affairs. She made the connection for me and Barbara Jordan gave me 20 minutes for an interview. I was able to get all of the information. I had to have all of my questions in order.

Kai Wright: I know one of the things that stood out for you when you spoke was the way she spoke, her actual style of speech. Tell me about that. Tell me about the way she spoke, struck you.

Reverend Bell: It always fascinated me. She had that oration that was just, you couldn't be doing other things and not listen. She just had that command. I was interviewing her nervous because I wanted to make sure I asked the right questions. I'm talking to a Congresswoman, and all of that was going on. As she answered the questions, she was classic Barbara Jordan, and I believe this. All of that was in there. Just that experience, but really what really touched me is she gave me 20 minutes of her time. She didn't have to, but she did. It made a difference for that A-grade paper, amen.

Kai Wright: You got an A, all right. Amen. Let's hear a bit of what you mean about the way she spoke. Here's a bit of Barbara Jordan in one of her historic moments. She was the first Black woman to give a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. This was 1976, as the party nominated Jimmy Carter for the presidency.

Participant: Ladies and gentlemen, in case you don't know it, may I now present our second keynote speaker, the Honorable Barbara Jordan, Democrat of Houston, Texas. [applause]

Barbara Jordan: It was 144 years ago that members of the Democratic Party first met in convention to select a presidential candidate. Since that time, Democrats have continued to convene once every four years and draft a party platform and nominate a presidential candidate. Our meeting this week is a continuation of that tradition, but there is something different about tonight. There is something special about tonight. What is different? What is special? I, Barbara Jordan, am a keynote speaker.

[applause]

Kai Wright: That was Barbara Jordan at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. I'm also joined, as I said, by Mary Ellen Curtin. Her upcoming biography is called, She Changed the Nation, Barbara Jordan's Life and Legacy in Black Politics. It's due out in September. Mary Ellen, talk to me about Barbara Jordan's manner of speech. It is so distinctive, we can hear there. Is that an oratory style she developed or was that just who she was? Tell me about the way she talked.

Mary Ellen Curtin: Well, it's both of those things and more. You really have to root her in her Black church, her Black family, her Black community, Black literature. Really, she's a product of all those things. Her mother and her father were both orators. Her mother was an orator as a young woman in this church, in the Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church before she got married. Her father was also a minister and he had his own church for a while. When she was very young, he had her recite to the congregation. She recited, as she said, about a thousand times, James Weldon Johnson's famous poem, The Creation.

You can't get something more deeply embedded in the Black experience than that poem. She was used to talking to a Black audience and having that feel. It was also her Aunt Mamie, who was a music teacher, who not only taught her how to sing, but taught her that when you're singing, you are really establishing a relationship with your audience. You're not just vocalizing. You're not just trying to hit the right note. You are communicating. You are creating a relationship. I think that really carried over into her speaking voice. She's very aware of the impact that she wants to have on her audience.

Her minister, Reverend Lucas, also was able, he was an example to her all of her life of someone who could command an audience and evoke, teach, but also evoke a response. I think all of those examples, including her debate coach, Thomas Freeman, she had so many important Black mentors that taught her along the way. She really is the culmination of all those experiences.

Kai Wright: As I said, there are a number of people today, particularly younger people, for whom they may be listening to this and being like, "Oh, Barbara Jordan now, who is that?" Introduce those folks to this person. What made you want to write a biography of Barbara Jordan?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Right. Well, first of all, I grew up in the ‘70s, and I remember her very well from that period. When I got older and was in graduate school and studying all these great heroes, studying Black history and studying all these great heroes of the Black freedom movement, and I just wondered, "How does she fit into this?" Because we all know that she was a great individual. She had these milestones that she hit, these barriers that she broke. Her connection with the Black freedom struggle was never quite made clear, I think, in what was written about her, because she was so exceptional. It was hard not to focus on her achievements. Her connections with the Black community and the Black struggle, that was a little trickier to elucidate and figure out. Again, to do that you really have to get into her history here in Houston. That's what I did.

Kai Wright: We'll get into that in a moment, but Reverend Bell, getting back to your interview before we have to go to a break. I know one thing that stuck out for you was her devotion to the Constitution. Tell me about that. What did she say that made you feel that way and why did that stick with you?

Reverend Bell: When I decided to write the paper and I'm a proponent of statehood. I needed an opposing view and because of her position on the Constitution, the government needed to have a seat of government is what she pointed out to me. Just in asking my questions, one of her first answers, she went into the Barbara Jordan. She says I'm a debutante of the Constitution. I got stuck on the word debutante. I'm like, "Okay, I don't know what that word means. How do I keep going?" It took me three days to figure out what that word meant, but she was really telling me she was devoted to the Constitution and because of that, that's why she believes that the federal government should have a seat of government a place. That particular view helped me to just prepare the paper and show two opposed sides to it. Very helpful.

Kai Wright: Just ahead, we're going to learn how she gained global recognition as a defender of the Constitution by leading the Congressional hearings on Richard Nixon's impeachment. Reverend Bell, thanks for helping us get started. Mary Ellen Curtin is going to stick around as we learn more about Barbara Jordan. I'm Kai Wright. This is a special edition of Notes from America coming to you from Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Houston, Texas to celebrate Juneteenth. Here's a bit of Good Hope Choir. You're going to hear right now more just ahead, stay with us.

[MUSIC - Good Hope Choir: God is doing something wonderful in Me]

Barbara Jordan: A president is impeachable if he attempts to subvert the Constitution. If the impeachment provision in the Constitution of the United States will not reach the offenses charged here, then perhaps that 18th-century constitution should be abandoned to a 20th-century paper shredder. As the President committed offenses and planned and directed and acquiesced, and a course of conduct which the Constitution will not tolerate. That's the question. We know that, we know the question. We should now forthwith proceed to answer the question. It is reason and not passion, which must guide our deliberations, guide our debate, and guide our decision.

[MUSIC]

Kai Wright: Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright, and this is a special edition of Notes from America coming to you from the historic Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Houston, Texas.

[applause]

We are here this week in partnership with Houston Public Media and with AHF's, We The People Coalition to celebrate Juneteenth and think about the ways Black America built our democracy. What you just heard is part of a speech that maybe depending on your age you never heard, but in 1973, this speech broadcast on national television set the country a flame.

It's the late Congresswoman Barbara Jordan as she opens the house impeachment hearings of Richard Nixon. I'm joined by historian Mary Ellen Curtin. Her book, which is due out later this year, is called She Changed the Nation: Barbara Jordan’s Life and Legacy in Black Politics. Mary Ellen, let's get into this moment in history, set the scene for that speech,. What's going on in the country, and why is Barbara Jordan in the middle of it?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Great questions. In the summer of 1974, the House Judiciary Committee, which she was a member of had been a meeting in isolation. They'd been almost sequestered. They'd been listening to John Dore who was laying out the case for why President Nixon should be impeached. There were all kinds of conversations happening within that committee behind the scenes. There was a group of folks who were undecided. You also had defenders of President Nixon, one, in particular, Charles Wiggins of California, who insisted that it would be wrong to vote for impeachment unless you absolutely believed and could prove that the President could be convicted of a crime.

This is something that Barbara Jordan took issue with and was constantly arguing with him about because he could be very persuasive. There was a group of people called the undecided Republicans and Democrats who were uncertain about whether they should vote this way. It was very important for the chair of the committee, Chairman Rodino, to have a bipartisan vote. It wasn't just Democrats over Republicans. You really needed not just a majority, but people who would otherwise want to defend the President realize this was what they needed to do.

Her argument when she makes this speech, she is addressing them, these undecideds as well as the nation. This is the first time the nation is really hearing the arguments for impeachment. The Congress knows them, the Judiciary Committee knows them, but the public doesn't because they've been meeting in secret in private, and now she's explaining to the public what is going on and why impeachment is necessary. It's really important to look at what she says, how she says it, and why she puts it in this way.

Kai Wright: I said it set the country of flame. Is that true? Is that a fair characterization of what was the reaction?

Mary Ellen Curtin: It's true because the clarity of which she laid out the grounds for impeachment by juxtaposing what the president said and did against the criterion for impeachment that had been laid out in these state conventions was so clear to people that afterwards everyone wanted a copy of the speech. The journalist said that she's the best mind on the committee. There was a real excitement and buzz when she finished and came out. She also gave the speech during prime time. Again, this is when there's three stations all which are being televised. This is 9:00 PM. This is when America is tuned in. Absolutely her speech made a difference. The way she framed it in terms of the Constitution, I think is very important.

Kai Wright: The content, let's be clear, was part of that. Did it have anything to do with who she was? She was a 30 what, 36-year-old?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Yes. She was young.

Kai Wright: Black woman at the time.

Mary Ellen Curtin: Yes, it did. One of the way she frames the speech is by talking about the Constitution and saying my faith in the Constitution is complete. It's total. Whenever she was asked about that saying look, "There's a lot of problems with America. How can you profess this faith? " She'd say, "Well, you have to remember what I said at the beginning of this speech." At the beginning of this speech, she echoes Frederick Douglass of all people. Frederick Douglass' 4th of July speech where he says, "I am not included in your holiday." She says I was not included in the original Constitution but now through the process of judicial review, I am now included. All right.

This is what makes this document so important, so vital. The reason she wants to highlight the significance of the Constitution is because ultimately her goal is to make the argument that of the gravity of President Nixon's crimes. If the Constitution is a sham, if it doesn't mean anything, then who cares if you violated it? What she wants to argue is that yes, the Constitution matters. What President Nixon did is merits impeachment, and these are grave things that he did. The Constitution also is important because it's wrong. She says it's an error to say, "You have to think he's guilty to vote for impeachment." She says "No, the Constitution doesn't say that. It makes the House the accusers, but not the judges. You're not judging whether he's guilty or not, you're just making an assessment, a decision over whether there's a possibility there. This is a check on abuse of power, and this is something that's our duty to do." These were important arguments to make so that the nation understands, and undecided members of the committee can understand as well.

Kai Wright: Barbara Jordan grew up in this congregation here at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church. We have a question from somebody in the congregation who asks as we're in her home church, can you speak to the role faith played in Representative Jordan's leadership?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Yes. I think that certainly a lot of her speaking she knows her Bible to say the least. I think it helps her maintain optimism. One of the quotes, "in faith to risk belief in American democracy." I think that comes from her faith. When she was governor for a day in 1972, before she goes to Washington, she gives a very moving speech at the Texas State House where she says to everyone gathered, most of whom were from the Fifth Ward, she says, "I want you to stand behind me and help me move this nation." She quotes the Bible and she says, "It does not yet appear what we shall be."

The future is there in front of us. We have to have faith in the future. I also think she relied a great deal on members of the congregation for political support. The women who worked for her, who went door to door, who did all of that hard campaigning, who she inspired. She really went and spoke in so many churches when she was campaigning for office. I think it was very influential and very important to her personally and also as a candidate.

Kai Wright: Well, and she grew up around the civil rights movement coming out of this church as well. There was this congregation as well. There was an important civil rights case here. I wonder if you can give us a quick synopsis of and why it's important. Smith v. Allwright. One of the plaintiffs was a member of this congregation.

Mary Ellen Curtin: That's right. Before you have the Civil Rights Movement here in Texas, you had a voting rights movement in the 1940s. One of the leaders of that movement was the minister of this church, Reverend Albert A. Lucas. He was a monumental figure. He was a crusader. I have to really thank the librarian of this church, Sarah Scarborough, who was the person who talked to me about Reverend Lucas and really emphasized his significance. Reverend Lucas was a crusader. He was chair of the NAACP of the state of Texas, not just Houston. He really helped to mobilize the communities to raise money for the case.

He went to the NAACP convention in Philadelphia to argue, make the case for why Houston should be the site of the next annual convention, which was in 1941. We went to Philadelphia, made the case people, voted for Houston over Los Angeles, which is interesting, and said, "No, you should be here. Where things are happening, you need to see the soldiers on the ground." Thurgood Marshall was here, A. Philip Randolph was here. Richard Wright was here to accept the Spring Iron Medal. All in Good Hope. This little working-class church in the poor fourth ward attracted all of these Black luminaries from all over the nation, and it really helped to mobilize the significant-- and voter education was an incredibly important part of that meeting.

Because of that, they were able to raise money. Dr. Smith, you need to talk about him as a courageous individual, because he had to go and try and get a ballot and try to vote in that white-only primary because Blacks who had been excluded from voting in the Democratic primary and excluded from joining the Democratic Party. He went, he tried to cast a ballot and he was turned away. That took a lot of courage. Because he did that though, he could become one year later the plaintiff in Thurgood Marshall's case. He had the evidence for that.

He had been harmed and then eventually that case becomes Smith v. Allwright. In 1944, when that case is decided, the joy, everybody came to Good Hope to celebrate there was such a huge crowd. Dr. Smith, he couldn't walk through the doors, he had to be pushed through the windows in the back. Thurgood Marshall was here, and he witnesses the whole thing. It's quite an event and it's one of the most important Supreme Court decisions. It's on par with Brown in terms of what it does for opening up the political process for Black Americans.

Kai Wright: How do you think growing up in that milieu shaped? When you think about this person who was like, I had a real understanding of the constitution, who decided, again, as I said earlier in the show, to be one of the first people post Voting Rights Act to say, "You know what? Government. I'm going to go into government, I'm going to--" How do you think that history impacted her ambitions?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Well, you have to say she was elected before the Voting Rights Act.

Kai Wright: Fair enough.

Mary Ellen Curtin: Which makes it all the more amazing.

Kai Wright: He first election is in 1960--

Mary Ellen Curtin: Well, she runs in '62 and in '64, and she's defeated and then finally she's elected in '66, but she is part of a coalition movement of liberal, they call themselves the Democratic co-- they were part of a group of Democrats who wanted to upend and end Conservative rule of the party in Texas. They are involved in nonviolent direct action, but they're also involved in litigation. One of the things they did was bring lawsuits against the unfair way that the state houses were districted. They brought lawsuits for redistricting, and that is how she was able to get a seat in the Senate.

She always understood the power of the courts for making the Black vote meaningful, because without redistricting, she said I never would've been elected. She also understood the importance of the Black vote in being a powerful leveraging force, that it could decide elections, it could decide primary elections, and we still see that. We'll get to this later, but we still see that today. Part of working with others in the Democratic Party, it was a coalition of Labor, and Liberals, and Latinos, they all had a goal, which was to make the Democratic Party fairer and more representative and to bring the ideals of the civil rights movement into governance. That was always her goal.

Kai Wright: We walked around Houston and talked to people about Barbara Jordan. Many of the people, as I said, we approached, the young people weren't immediately aware of her, but once we told them they had lots of questions as well. I want to share some of those. Here's one question. We got this question in a bunch of different ways.

Participant: How hard was this for getting established with times being so different back then? What was her experience with coming up and just knocking down different walls for women to be able to hold that type of position?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Well, Black women were deeply involved in the civic life of Houston. You had Fifth Ward Civic Clubs, and you had Ms. Hattie Mae White who had been served on the school board in Texas. To compete in a primary race and to beat a white male opponent, that was not easy. She made it look easy because in the end, she got an overwhelming number of votes. In that primary race, there was some resentment even among other Liberals who thought, no, her opponent said it, "Well, I have served in the Texas House and now it's my turn to serve in the Senate." She had to say, "It's not your turn. I have worked for the Democratic Party. I have brought Black voters into this coalition, and now I have a seat that I can win, and this is something that I should be endorsed."

She had to fight for that. Even though she was part of that coalition, she really had to fight and put herself out there and insist that she was the proper person to represent the Fifth Ward and Black Houston in the Senate. Nothing was given. Everything has to be fought for. I think for her especially. Yes, to put herself out there and to insist that she was the right person, that took a lot of courage, a lot of guts and determination, and ambition.

Kai Wright: This is a special Juneteenth edition of Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and I'm talking with American University Scholar, Mary Ellen Curtin, author of the upcoming book, She Changed the Nation: Barbara Jordan’s Life and Legacy in Black Politics. We are here at Barbara Jordan's Lifelong Church Home, the historic Good Hope Missionary Baptist to church in Houston, Texas. More just ahead.

[Applause]

Barbara Jordan: We are a people in a quandary about the present. We are a people in search of our future. We are a people in search of a national community. We are a people trying not only to solve the problems of the present unemployment, inflation, but we are attempting on a larger scale to fulfill the promise of America. We are attempting to fulfill our national purpose to create and sustain a society in which all of us are equal.

[applause]

A spirit of harmony will survive in America only if each of us remembers that we share a common destiny. If each of us remembers when self-interest and bitterness seem to prevail that we share a common destiny.

[MUSIC - Louis Armstrong]

Regina de Heer: Hi, I'm Regina, a producer here at Notes from America with Kai Wright. I hope you're loving this episode. As you know, we cover a lot of issues and ideas on this podcast, and we don't want to do it without you. Having your questions, stories, and experiences in the conversation is so important to us. Let me tell you how to be in touch. In the show notes of this episode, there's a link that takes you to our website notesfromamerica.org where you can record a message for us, plus our inbox is always open at notes@wnyc.org. You can write us or even better record a voice memo on your phone and send it to us there. That's notes@wnyc.org. I'll be looking there for a note from you soon. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC - Louis Armstrong: St. James Infirmary]

Kai Wright: Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright, and this is a special Juneteenth edition of Notes from America Coming to you from the sanctuary of the Historic Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Houston, Texas.

[applause]

We are talking about the late congresswoman Barbara Jordan, who grew up in this congregation. She came from a very musical family and that Louis Armstrong song that we just heard a little bit of that was her favorite song. It's called St. James Infirmary. With us today is American University's scholar Mary Ellen Curtin who has written an anticipated biography of Barbara Jordan that's due out later this year. As we turn to talk about things in the present day, I am also joined by Sonny Messiah-Jiles who is the CEO and publisher of The Defender Media Group which is Houston's Black community news organization. Welcome to Notes from America, Sonny.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: Thanks for the invitation.

Kai Wright: You've been listening to us talk about Barbara Jordan. I just want to start with your general reaction to what you've heard thinking about her legacy today.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: Thinking about her legacy I think that there are a few things that need to be shouted out. One of them is she's a Fifth Ward native.

[applause]

As a result, I knew that would create some rounds all in the house of Fifth Ward. Fifth Ward Texas baby is what they call it.

Kai Wright: All right.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: Then there's Texas Southern and Dr. Thomas Freeman, who played a significant role in her articulation and clarity of her message. I think, yes, Good Hope and all of her youth helped shape her being a speaker. I think that her skills were developed by Dr. Freeman. To give him a shout-out is important. There's so many people who followed in her footsteps, everybody from the Mickey Leland and the Ruth Simmons, and the list goes on and on. I needed to at least acknowledge that because Barbara Jordan was a fighter. I think that's part of that Fifth Ward spirit. I think that just the fact that she lost two races and then came back and one ascended race, it was a male-dominated environment. As a result, I think she was fighting on two fronts, not just Black, but women also.

With that, I think that is one of the Mary Ellen pieces that she was fighting on multiple fronts. I think also though that Kai, one of the areas that I think oftentimes is understated is the fact she never came out of the closet, but she never stepped back from who she was. She was always there and in her own self, proud of where she was and who she was. I think because of that, the LGBTQ community was able to utilize her as one of their pillars of strength that showed that leadership and politics was something that their community could also do.

Kai Wright: Mary Ellen, I think what Sonny's referring to is of course Barbara Jordan's lifelong or our decades-long relationship with Nancy Earl which was not something that she talked a lot about, but not something that she didn't talk about. What in your research about her and that relationship you think is relevant to today?

Mary Ellen Curtin: I think that it's clear that Nancy Earl played a huge role in just being a support. She traveled with her, worked in her office, helped her with so many things. It was a real booster. There's no question about the significance of that relationship. It's funny, no one really asked her. It's not like anyone ever said.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: Behind closed doors people were talking all the time, let's be real.

Mary Ellen Curtin: In terms of publicly, whether this whole thing about like I agree, she was never in the closet in that they went places together. Nancy Earl accompanied her. I think that Barbara Jordan very much valued her independence and valued her privacy. This is also true about her health, her health issues as well. She valued her privacy but at the same time I think you're right, she never really denied her relationship.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: I think what trumped it all, for lack of a better word, was the fact that her community advocacy, her loyalty to fairness, and her belief in the Constitution, those elements I think didn't matter where you came from, what you did, who you were about, it was more of what was your mission. Her mission was clear.

Kai Wright: I'm glad we got to Texas Southern. Texas Southern is a historically Black college and university here in Houston. We had several questions from the audience about Texas Southern, but I think you've covered them, but I wanted to name. There are folks here who wanted to hear more about Texas Southern. As I mentioned, we walked around Houston asking people if they had questions about Barbara Jordan. Here's one more I want to play for both of you.

Participant: "With Texas being Texas, a majority Republican state, did that matter as much to her Democrat versus Republican as far or did it matter more to push the agenda of the Black community because now the agenda of the Black community seems to be more so handcuffed or allocated to the Democratic party, but was it the same at that time?"

Kai Wright: Mary Ellen, let's start with you. What were things like in Barbara Jordan's era when it comes to partisanship? Was the Black community so tied to the Democratic party then and how did that change?

Mary Ellen Curtin: She's very partisan and she's a very strong Democrat not because she wants to follow the Democratic party, but because she wants to change it, she wants to transform it, she wants to make it into an instrument for social injustice and for equality as best as she can. She really wants people to have that belief, to risk that belief, and that you're not just blindly following something, but that you have an opportunity here in this two-party system to participate in a party that there's an opportunity to make it work for your benefit and to remove the obstacles that had been there. This is a core belief as she says in the '76 speech of what the Democrats are all about. They're inclusive, they're diverse, they're committed to removing obstacles to progress. She wants people to be enthusiastic about that project.

Kai Wright: It's interesting because we think just historically about when did the Black community becomes so closely tied to the Democratic Party, and we think about that as the Roosevelt's era, but that's not correct.

Mary Ellen Curtin: Well, it is, and depending on what region, because in the North yes, but in the South Black voting was again dangerous, especially in the 1930s.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: Democrats were not that interested in seeing Black folks vote.

Mary Ellen Curtin: Exactly. It's the party of white supremacy. It's the party of white rule. This is why the energy and commitment that went into upending that really is so important for understanding the civil rights movement, and what the Black Democrats in Texas tried to do is change that party, and her speech in '76 really is about exercising those ghosts.

Kai Wright: Sonny, let me ask you two things. One the person's question about partisanship that we heard in her part of the question that was about now. Does it feel like in Texas and Houston that the Black agenda is so closely tied to the Democratic Party, and what do we think about that? Another question from the audience, I want to pair with that for you, the audience here is given the blatant gerrymandering used to dilute voting power of communities of color, have we really progressed in the years since 1944 with Smith v. Allwright out of this community? Can I put those two things together for you? Just thinking about partisanship and Black politics in this area now and then given gerrymandering, where is the power of the Black community electorally now?

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: I think historically the Black community has always had to fight, whether within the Democratic Party or outside of the Democratic Party, there's never been a fair share of equity. If you were talked to some of the Congress people today, you would find out from them that they're still having to fight internally for equitable shares of leadership and decision-making, but I think during Barbara's term, it was much harder because the white Democrats were not that excited about giving Black Democrats power.

Let's not get it twisted. She was having to fight that battle also. It was three fronts. It was more of a trifecta that was going on. She was fighting the white Democrats.

She was fighting males that were Black, and she was fighting for women to be able to get an equitable share. When you look at it from that perspective, Barbara was definitely a crusader and a warrior and a shero. When you transition that to today, okay? I do think that the reality is it doesn't matter which party you're going to be in, you still got to fight for equitable share. Neither one of them wants to give you Jack, and I think that because of that, we as Black people have to leverage our power to mean something, to count for something. We can't just give it away because it's there, but it's boiling down. When you look at this race that's coming up, it's like it's Black and white almost.

It's very clear as to who is in the interest of Black people based on things like Project 2025.

Kai Wright: Project 2025, that's the blueprint produced by the Conservative Heritage Foundation. It's one of several think tank proposals that have been aired that reveal what Trump's platform will be if he is elected. Let me ask you this, certainly in Democratic Party circles, there is a great deal of anxiety about Black people not voting in this election. Do you share that anxiety?

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: I share the anxiety only from the standpoint of you better get off your behind and vote. The reality is that, I'm going to look at a few notes that I have here because I knew this question was going to probably come up. When you look at the fact that Project 2025, which is this plan of action that's supposed to go into effect if Trump is elected. One of the things says they're going to eliminate the Department of Education. Well, you think Black kids are having problems in education today with federal regulation? Guess what it's going to be like without it.

Two is that they're going to eliminate DEI programs. They've already succeeded on the Supreme Court with the elimination in universities, being able to recruit people of color to the universities as our whole United States becomes more of color, and then they're going to try to destroy contracts when in Harris County, we just got through doing a number of disparity studies that say Blacks are getting less than 5% of the contracts, and you want to take that also?

Then look at you, Kai, they're talking about defunding public media. Eliminating NPR and PBS.

Kai Wright: Well, likely we actually depend on the donations of our members.

[crosstalk]

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: People giving private donations. The reality is this plan is a plan that is really against public interest, and so as a result, people have to wake up. Here's the reality.

Kai Wright: Do you think people know that? Do you think people feel that way?

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: I think that the Democratic Party has a messaging problem and that they have to work on their messaging. I think part of that has to do with look at the facts. Open your eyes. If women's rights are being taken right now regarding their healthcare, what could be taken from Black people? A lot of things. Not that we've achieved a lot of parity and equity, but it's definitely better than it was back in Barbara Jordan's day.

Kai Wright: Mary Ellen, Barbara Jordan was famously adept at moving voting blocks. Tell me about that. How did she come to that [unintelligible 00:45:38] how did she use it and how did she come to it?

Mary Ellen Curtin: You mean how did--

[crosstalk]

Kai Wright: Her understanding that she needed a voting block and that she knew how to put it together?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Oh, well, I think it goes back to this coalition building that comes out of Houston, that she understood. At the same time she made sure her campaign headquarters was in the Fifth Ward. It was on Lyons Avenue. She understood that you have to be strong within the coalition in order to be taken seriously, so she really tried to do both things. She wanted to mobilize Black voters and she wanted to make alliances with like-minded folks.

This goes back to Bayard Rustin talking about how we really have to think about how to-- the Democrats are still trying to do this. They're trying not meld these interests, but balance them, and make people work together. It's not easy. It's never been easy, but it's the only option that we have now, and to get the vote out to mobilize people to go door to door, all that heavy work. That's a heavy lift and people have to get out and do it. That would be her message.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: I think Barbara understood that the holder is only as strong as the parts, and she was very strategic in how she put those parts together, whether that was the Black church, or whether it was the Labor, or whether it was the community in general, the educators. She had a way of targeting different groups, and that coalition of those groups is what helped her ride to victory.

Kai Wright: Mary Ellen, we talked at length about impeachment of Richard Nixon, the obvious elephant in this conversation [chuckles] is Donald Trump. I don't know if it's fair to ask you, but what do you think Barbara Jordan's role would be, or reaction would be to the moment we're in now of searching for accountability for Donald Trump?

Mary Ellen Curtin: Oh, well, I think she'd be all over it. If it had gone to trial because Steve Nixon had resigned. She was going to be chosen as part of the prosecuting team in the House. Because if it goes to trial, you needed people in the House to make the case for impeachment. Chairman Rodino was going to choose her to lead that. She would've played a very important role in that impeachment proceeding, and I have no doubt that if she were here today, she would be right with Jamie Raskin and the rest. She would be very-- you need the reason and the storm.

This is Frederick Douglas. Even though she talks about its reason that much guy that which should guide us, she brought the storm too. She brought both passion and reason, and that is one reason I think she's so persuasive.

Sonny Messiah-Jiles: I think she was very, even when she may have alluded to Frederick Douglas' July 4th speech, she believed that power concedes nothing without a demand, and knowing that, then I pulled one of the quotes that she had and it said, "This imperative is clear. We must make a government that works for all Americans, not just the privileged few." I think that applies to the Trump situation.

Kai Wright: Well, we will give that the last word then. Sonny Messiah-Jiles is the CEO and publisher of The Defender Houston's Black Community News organization. Mary Ellen Curtin studies the history of Black American and women's politics at American University. Her forthcoming biography of Barbara Jordan is called She Changed the Nation: Barbara Jordan’s Life and Legacy in Black Politics. It's to be published on September 10th. Thank you both so much for your time.

[music]

This show was produced by Regina de Heer and so many people helped it come together. Thank you to Rice University. Thanks also to our station partner, Houston Public Media, and to the good folks at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church.

[applause]

Special thanks to our event partner, AHF through its We The People Coalition. You can learn more about We The People marching forward to protect democracy at wtpmarch.org, and thank you for listening.

Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. Find us where you get your podcast and follow us on Instagram @noteswithkai. You can keep engaging with our show there and with lots more from today's special broadcast that we're going to share. I'm Kai Wright. Happy Juneteenth.

[applause]

[music]

[00:50:33] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.