A History of the Palestinian Solidarity Movement Through One Activist's Life Story

[MUSIC]

Protester 1: For almost 10 months and 75 years, Palestinians have been resisting. For 10 months and 75 years, we have stood alongside them from here, the belly of the beast.

Protester 2: Since October, I've been to over 30 protests. This has just been ingrained in me since I was born. This is something that me and all other Palestinians will never turn their back on.

Protester 3: We stand on the shoulders of those who came from before us, and we will continue building and sustaining this movement.

Protester 4: We are here because our people in the West Bank and Gaza have suffered immeasurable, horrific carnage. These are our families. They will not be forgotten.

Kai Wright: It's Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show.

When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressed a joint session of the US Congress last week, roughly half of the Democratic caucus skipped it, including the party's new standard bearer, Vice President Kamala Harris. There's a lot of reasons for that. Absolutely, one of them is the mass movement that has grown in solidarity with Palestinians in Gaza. It just has meaningfully shifted the politics within the Democratic Party, and that's a big political change. As with all change, there's a lot of history leading up to this moment. I've been talking about that history with our producer, Suzanne Gaber.

Hey, Suzanne.

Suzanne Gaber: Hey, Kai. Over the last nine months, especially as we head into what is looking to be a very tight presidential election, there's been a lot of discussion around Arab American politics and the connection to pro-Palestine protests that we've seen all around the country since the start of the war in Gaza.

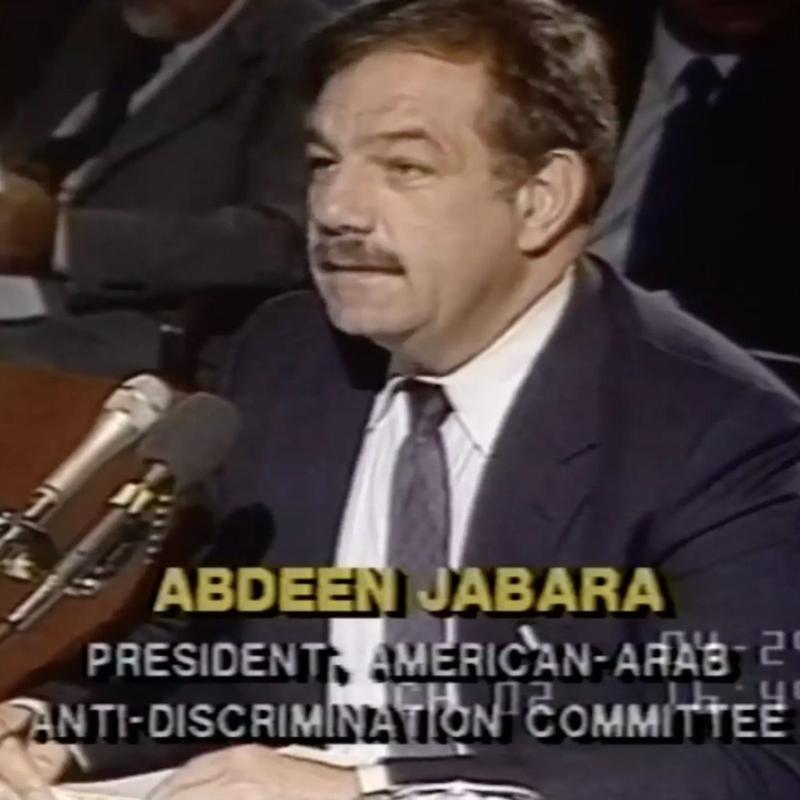

To me, it's felt like people are just realizing we exist, and that this connection to Palestine came out of just the last year. There's a long history in my community's politics. Our connections to each other as a community have changed over time. I wanted to explore that history a little bit. There's this man named Abdeen Jabara who I've been thinking about a lot. He's someone I've spoken to a few times in my reporting on Arab American history. He's a civil rights lawyer. He's been at the forefront of a lot of discussions around Arab American identities since the 1960s. He's really examined our relationship to the US government, and how Palestine and the rights of Palestinians have shaped that relationship. I wanted to introduce you and our audience to him.

Abdeen Jabara: Hi.

Kai Wright: It stopped raining.

Kai Wright: Suzanne and I drove up to the Catskills in New York, where this 83-year-old legal activist was taking a break and visiting friends.

Abdeen Jabara: I'd like you to meet Karen here. She's my hostess with the mostest.

Kai Wright: Suzanne brought some sweets, because that's what you do. You do not show up empty handed.

Abdeen Jabara: Oh, my goodness. Oh, look what they brought us for dessert tonight.

Karen: Oh wow!

Kai Wright: I knew that Abdeen has been involved in so much civil rights work. Suzanne has been telling me that much. Also, some of that work is complex and nuanced and has meant doing stuff like providing legal defense to people who committed horrifying acts of violence. He's a man with strong convictions, and he's lived through a lot. At his core, he still sees himself as a small-town boy from Michigan, which is where he grew up in the 1940s at a time that's really early in the story of Arab Americans collective history.

What was it like growing up in an Arab family at that time? What was the Arab American community like at that moment?

Abdeen Jabara: My family and my uncle's family were the only Arabs in that town. It was a town of about 900, and we were pretty integrated into the town. It was not like we felt any discrimination. My father was very hard-working immigrant. Our family were upper middle class. My parents were involved in civic life there. There was something wrong with the town. There was an unincorporated part of the town. The other part of the town was called Antrim, and it was a company town. They had an iron foundry there where they brought iron ore from the Upper Peninsula. They harvested all this hardwood in the area, because they made coke, and they smelted this iron ore. They brought the workers for this foundry up from Kentucky. They paid them in company script that they used to buy groceries within the company's store. The children of those people went to the school in town. I don't know, I had this sense there was this big divide, and it was largely an economic one.

Kai Wright: It bothered you, that idea?

Abdeen Jabara: It bothered me a lot. It very much bothered me. That's how I gained my political consciousness and desire to make a difference.

Kai Wright: You mentioned that there wasn't much of an Arab American community. It was you and another family.

Abdeen Jabara: That's right. My father was a grocer. He believed in this country. He was a Republican. He was a founding member of the American Legion in Mancelona back in the 1920s, because he served a short time in the army. He marched every year in the Memorial Day parade. He also had a very strong feeling for the village life and the area that he came from. For instance, he would speak Arabic to some of the other siblings in the store when we were there, because we all worked in this grocery store.

They would get angry with him and tell him, "Dad, you shouldn't talk Arabic in front of the customers." My dad would tell them, "Look, I'm going to talk Arabic to you in the store and in the street and at home. If you don't like it, you can get out of here." That's the feeling we had. When some of our customers or people would come in to ask him, and they'd say, "Sam—" His actual name was Mohammed, all right. Everybody knew him as Sam. They would come in and ask him, "Sam, where are you from? Where did your family come from?" There would be these big cardboard boxes of groceries and so forth. He'd draw a map on there of the Middle East to show them and say, "This is where we come from." He wasn't ashamed of that.

Suzanne Gaber: Kai, I want to step in here, because as he's saying this, I couldn't stop thinking about my own Arab immigrant father and all the times I watched him have almost this exact interaction. I also didn't have a large Arab community around me growing up. My dad, like Abdeen's, took it upon himself to be the person in our community to educate the people around us about our heritage. When I was trying to blend in as a kid, I didn't love it. It felt like a stereotype of the proud immigrant father. That's who my dad is. I appreciate it so much now.

The story made me connect to Abdeen's experience with his dad. It really made me feel for him even more when I learned that his father had been killed just a few years later in a car crash when Abdeen was 10 years old, and Abdeen was in the car with him.

Kai Wright: You were with your father when he died in the car crash?

Abdeen Jabara: Yes, I was.

Kai Wright: Do you remember that experience?

Abdeen Jabara: I remember waking up in the hospital. I had been basically unconscious for about three days, I guess. I had a cast all down my left leg and halfway down my right leg and a bar between them. I didn't know what had happened. I didn't know. My family didn't tell me that my father had been killed, because they thought it would impair my recovery. It took me a number of months before I recovered. After I did recover, like all the rest of my siblings, we all worked very hard in that grocery store.

Kai Wright: At what point did you begin to think about your experience as an Arab American?

Abdeen Jabara: It was during high school. I used to set up displays in the school in the display cases with artifacts that I had. We had at home trays, coffee urns, et cetera. I was hoping that I could help to convey to them something about this particular ethnicity that Americans were not at all familiar with.

Kai Wright: Suzanne, he's talking about a really different time from today. You want to just give us some quick context on this?

Suzanne Gaber: Yes. This is the 1950s, and it was just in the past decade that many of the modern states that we think of in the region came into existence, at least in the forms that we know them today. For Abdeen's father, there was no State of Lebanon. That didn't happen until 1943. For the region, there was no Israel.

For a lot of Americans, the Middle East just wasn't on their radar in the way that it is today, but Abdeen's father was thinking about it a lot. Abdeen has this very distinct memory from 1948 when he would come home from school and see his father listening to the radio where he'd be following the news reports of western governments carving up the region and creating the state of Israel.

Abdeen Jabara: When he used to lean down to that, I think it was a Stromberg-Carlson Radio. I would've been eight years old in 1948. My dad would come back from the store because where he worked all day long, and he'd turn on that shortwave radio, and he'd lean down and put his ear to the sneaker to listen to this Arabic sound. He was following these events that were happening over there. I had no idea what it was. He'd listen to it, and he'd get up and his face was not a happy face, but I just know why he was listening and what impact that it had on him.

Kai Wright: News of the partition?

Abdeen Jabara: Exactly. About the driving these people out of their villages, just driving them out.

Suzanne Gaber: You connected that to his experience living in the village, but he came from what then became Lebanon.

Abdeen Jabara: Right.

Suzanne Gaber: Why did the connection to Palestine, those in the American consciousness, are two different?

Abdeen Jabara: Well, because these borders, "Lebanon" were artificial. The people from my father's village, which is in this mountainous region next to Syria, they used to take their sheep and go and have them graze in Palestine, what became Palestine. There weren't these borders.

Kai Wright: To hear these reports of people being driven out of their villages didn't matter their "nationality." The point is that these were people-

Abdeen Jabara: That's right.

Kai Wright: -Arab people being driven out of villages.

Abdeen Jabara: Exactly. Just like mine. That's why all these people all over the Arab world support the Palestinian, because they don't care whether, they don't say, oh, he's a Palestinian. Some of these governments have tried to instill that in their people that these are different, but it's not succeeding.

Kai Wright: Coming up, how Abdeen Jabara found himself in the middle of massive historical events in the late 1960s, and how he became the first American citizen to prove that the National Security Agency was spying on him. This is Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright. Stay with us.

Regina de Heer: Hi, it's Regina, a producer with the show. It's time for our third annual Notes From America Summer playlist. It's an election year and we're feeling a lot of emotions, to say the least. A lot of us don't feel represented or heard, but we at Notes From America want to hear from you. No matter where you land politically, tell us about your politics through song. What's a song that tells us something about your political priorities or your political identity?

Speaker 1: Small Axe by Bob Marley. There's a part of that song where he says, if you're the big tree, we are the small axe sharpen to cut you down.

If you are the big tree

We are the small axe

Speaker 2: He is talking about things like imperialism and colonialism. We have to be the small axe to really use our voice to push people and power.

Ready to cut you down

Regina de Heer: Okay, so now it's your turn. What is a song, artist, or album that represents your political priorities this election year? Leave us a message at 844-745-TALK. That's 844-745-8255, or you can send us a voice memo to notes@wnyc.org. You can find a link to the playlist in the show notes of this episode. Plus check us out on Instagram @NoteswithKai to hear what people have to say about their political song picks. I can't wait to hear from you.

Kai Wright: This is Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright, and I'm with our producer, Suzanne Gaber. Suzanne's been spending a lot of time reporting on and thinking about the history of Arab American civil rights generally, and also the ways in which the community's history is so closely tied to the history of the global movement for Palestinian rights. This week, she's introducing me to an important person in that history, a civil rights lawyer from Michigan named Abdeen Jabara.

Suzanne Gaber: Yes, Abdeen has been an important person in the community's political evolution since he was a young man in the 1960s. He went to law school and then he lived in the Middle East for a little bit. Then he moved back to Michigan in 1966, just before the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

Kai Wright: Suzanne, that's a long time ago, but it's a super important moment. Can you just remind people what happened in 1967?

News Anchor: For the third time, since its birth as an independent state, Israel is embroiled in a war with the Arab nations that surround it.

Suzanne Gaber: This was a six-day war between Israel and three neighboring Arab states, which ended in Israel taking control over huge swaths of territory from those states.

News Anchor: Jews from overseas have come to give their support in work and in blood.

Suzanne Gaber: It was also a moment of huge growth in the Palestinian liberation movement. Over the following years, there was tons of new organizing and resistance inside Palestine, but also around the world. The war galvanized Arab American activists, and the US government took notice, and there were also armed factions of resistance. Five years after the war, another world event triggered a much larger scale of surveillance of Arabs in the US.

News Anchor: This morning, armed Palestinian guerillas raided the sleeping quarters of the Israeli team.

Suzanne Gaber: In September of 1972, during the Munich Olympics, members of the Palestinian terror group, Black September, broke into the Israeli Olympic team's residence and killed 12 people. It was an event that shook the world. In the US, it was part of what led to something called Operation Boulder.

Kai Wright: What was Operation Boulder?

Abdeen Jabara: Operation Boulder was a program that was initiated by President Nixon, where he had designated the establishment of a state department governed committee that involved all of America's intelligence agencies, the Immigration Service, the Secret Service, et cetera, to actually do a survey of pro-Palestinian activists in the United States and to create a watch list. That's what Operation Boulder was.

Kai Wright: This was not something that was secret. This was something that they were happy to talk about?

Abdeen Jabara: Absolutely. They announced it. Actually, Palestinian activists in the United States had been under surveillance prior to the initiation of Operation Boulder, but it was surveillance by a private organization, and that was the Anti-Defamation League. When they began the Operation Boulder, the FBI really didn't know that much about the Palestinian activists, and they turned to the Anti-Defamation League for information. That's how they began targeting various people around the country, including myself.

Kai Wright: I gather that you learned about it, just reading a magazine. How did you discover Operation Boulder? Can you tell me that story?

Abdeen Jabara: I'll tell you. Number one, it was in the New York Times. Okay? That was the first time. The nature of it and the depth of it, I happened to pick up a Newsweek magazine. On the first section, they had something called the Periscope. In that, they said that 22 Palestinian activists in the United States had been targeted for wiretapping by the FBI.

I had been talking to people all over the country that were having problems, primarily immigration problems but some of them were involved surveillance and attempts to interview them. I gathered many affidavits of these people. I would create a collection of these affidavits of what was happening to these people.

The other thing that I told them, I said, "Even though you're not a citizen or permanent resident, you have the same basic First Amendment rights in this country as anybody else." I was very active in representing one organization, which is another way I found out about how I was targeted, and that was the Organization of Arab Students. This was an organization that had chapters on a number of campuses, because after the end of colonial control in much of the Middle East, the governments were interested in their young people getting educated in the west, and gathering the scientific knowledge, and backgrounds that they could somehow contribute to the building of their society.

Many Arab students came to the United States from Egypt, from Syria, from Palestine, from all over, and they formed this organization called The Organization of Arab Students, and I was their attorney. While I was representing them, they wanted to put on a convention, and they didn't have any money. They had no funding, so I lent them $1,000.

I said, "Fine, I'll give you $1,000. You can pay me back whenever you get the money." I didn't have much money, but I was committed to what they were doing, and I wanted to help them as much as I could. I gave them this $1,000, and then one day, one of my law partners went into this bank where I did not personally have an account. One of the employees who was dating somebody in our office whispered to him to come over, and he showed him a piece of paper that was being circulated in the bank. This is before computers and all this business. It was a list of about four organizational names, and four or five individual names, and my name was on that.

Kai Wright: This is a list from the government saying, "Watch these people."

Abdeen Jabara: I knew immediately that's what it was. I sued my bank, and they admitted that they had passed information about my account to the FBI. You know what the information was, it was $1,000 that I gave to the OAS.

Kai Wright: As best as you can remember, and as honest as you can remember, did it scare you? Did it piss you off?

Abdeen Jabara: I'll tell you. I'm glad you asked that question. When I found out about this taking information about my bank account, I was angry. I was angry, and I didn't really do much other than sue my own bank, and it was subsequent to that that I brought my lawsuit against the FBI. When they responded to the complaint, they refused to answer one allegation in it, and that was the allegation that I had been subjected to warrantless electronic surveillance.

I'll tell you, in terms of practicing law, the judge that you're assigned to makes all the difference. In this case, it was a judge who I had appeared before on other cases. He basically knew who I was. He knew I was not some fire eating terrorist, and we went through this whole process, and he ruled that the government had indeed violated my rights of privacy. We discovered something during the course of this lawsuit that was really pretty monumental. That was that the FBI had requested information from the National Security Agency whether they had any information about me, and they had obtained information about, I think it was four, six of my international communications, which they then handed over to the FBI, all of which was done without any legal process. That was the first time in the United States that any American had been able to prove that they had been surveilled by the NSA.

Suzanne Gaber: Kai, the case he brought against the FBI also revealed that Operation Boulder had led to the illegal surveillance of at least 150,000 Arabs in the US.

Kai Wright: Wow.

Suzanne Gaber: It was at the time the largest surveillance program in the US. I should say that the surveillance led to many deportation proceedings, including some where Abdeen served as the defense lawyer. Abdeen took the Operation Boulder case through the courts a few times with appeals in front of different judges. Eventually in 1985, the courts determined that the FBI had to destroy the records it had on Abdeen, ruling that the agency had violated his First Amendment rights.

Kai Wright: I imagine, Suzanne, that this was a big deal in the community at the time, but I've got to say it, of course, immediately makes me think about the same kind of surveillance that was targeted Arab Americans and people perceived to be Muslim after 9/11.

Suzanne Gaber: Yes. Actually, several civil rights experts I've talked to say that Operation Boulder ended up as somewhat of a blueprint for future surveillance efforts in the '90s, and then post 9/11. It didn't really stop that, but what it did do was confirm for many Arab Americans, myself included, that we're not paranoid, and without that knowledge, without being able to see cases like Abdeen's in print, it can be really destabilizing to experience yourself as a villain in the eyes of your government. It's really isolating, and it's something I've felt a lot growing up.

I was maybe being surveilled, but maybe was I just making this up in my head? I know a lot of my friends felt that way too, and I can hear a lot of those feelings, and that lack of certainty, and destabilization in the way that Abdeen talks about Arab American organizing after 1967, but before he realized he was being spied on.

Abdeen Jabara: It was a very trying time, and it took me some time to gather my senses, and to get involved in some organizing work in both in Detroit and nationally to try to convey a more positive impact about the whole Palestinian issue to the American people. One of the avenues that we did that with was this organization called the Association of Arab American University Graduates, because we felt incredibly isolated and under attack. We banded together this small group of, I had just opened my law practice in Detroit. I had very little business, so I became the first executive secretary of this organization. We began to start to build it, but they were not involved at all in American politics.

Kai Wright: What do you mean?

Abdeen Jabara: They didn't try to really understand the mechanisms in American society, and the role that campaign financing plays, the major role that it plays in our politics, which I think has now been exposed to some extent, although it's still a scandal. They were focused on basically trying to explain the Palestinian problem to the American people. We would have these conferences; they'd have these scholars come and give talks. We would compile the transcripts of those talks.

Kai Wright: It was like a consciousness raising effort.

Abdeen Jabara: I'll tell you where it did have an impact. It had an impact on the Middle East studies community and universities around the country. At that time, the whole Middle East studies program in the United States was very colonial. It was very state department oriented. It was not looking at the area that had been colonized after the--

Kai Wright: Training diplomats to go —

Abdeen Jabara: Exactly. We don't have to explain the whole history of the region, but basically the region was divided up by Britain and France, and they controlled those governments, and particularly the government of what was called Trans-Jordan, and Iraq, and Syria, and Lebanon, but people didn't understand any of that. We had to go out and give talks and explain that to people, and they understood as some people did. Then, of course, the big thing that came out of '67 was the rise of the Palestine Liberation Movement.

Suzanne Gaber: He's talking specifically about the creation of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, which many of us know as the PLO. Like I said earlier, there were many forms of Palestinian resistance coming up around this time, both violent and non-violent. For Abdeen, it was an exciting time where there was support for Palestinians growing in some circles, but for many Americans, the thing that came to the forefront, the places they interacted with Palestine the most had to do with violence. Abdeen actually served on the legal defense team for a few people accused of very high profile acts of violence, including one of the most famous political assassinations in US history.

News Anchor: Senator Robert Francis Kennedy died at 1:44 AM, June 6th, 1968.

News Anchor: Police identified the alleged assailant as 24-year-old Sirhan Sirhan, a native Jordanian who came to this country 11 years ago.

Kai Wright: Why did you think that was an important case for you to be part of?

Abdeen Jabara: I was attracted to it because when it happened, it was reported that Robert Kennedy was assassinated by a Jordanian. That was the first thing that raised the red flag.

Only later on did it come out that he was a Palestinian Jordanian, not just a Jordanian, because part of Palestine was absorbed into Jordan through machinations of the Israelis and the Hashemite monarchy in Jordan, and a lot of Palestinians became Jordanian. That's the first thing that piqued my interest. I wondered what is going on here, what is the relationship between Sirhan, his Palestinianness, and the assassination of Robert Kennedy. Sirhan was examined by a number of psychiatrists, given Rorschach tests, et cetera, et cetera. Some of his notebooks were entered into evidence that he kept at home, that even an amateur could look at them and see that there was something very wrong. He basically was suffering from some kind of a mental situation. I traced that to his experience as a child in Palestine.

Kai Wright: Why would you do that? Why? Here's this person who has being accused of shooting this revered man who's fighting for civil rights, and how is it, in your mind, helpful, and you're somebody who wants to stand up for the Palestinian liberation? Why? It seems like you would run as far as you could from somebody like Sirhan rather than running to him.

Abdeen Jabara: No. Absolutely not, because that Sirhan case is a case about what kind of impact this had on the people that suffered the Nakba. His family. His family came to this country as part of a group of Christian Palestinians that the Eisenhower administration gave special preference to come here. They settled in southern California, and they had so many problems. Oh my goodness. I can't tell you in terms of integration, et cetera. The father went back. He left everybody. He went back. Some of the family got in trouble with the law. There were all kinds of problems. All of these are traceable to the disruption of their lives in Palestine. Absolutely traceable. Back then, they didn't talk about post-traumatic stress disorder. Now, PTSD is a common usage in psychology. This was really basically a PTSD situation. Absolutely in my estimate.

Kai Wright: Coming up, the enduring perception in American culture that the words terrorist and Arab are synonymous. More of our conversation with Arab American legal activist, Abdeen Jabara, just ahead.

This is Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright, and I'm joined this week by our producer, Suzanne Gaber. She's been introducing me to a pivotal figure in the history of the Arab American community's political story, a civil rights lawyer and Palestinian rights activist named Abdeen Jabara.

Suzanne Gaber: Kai, as we've been discussing, my community's political history is so closely wound up in the history of US policy in the Middle East. Before break, we were hearing from Abdeen about his role in the defense team of Sirhan Sirhan, who is, of course, the Palestinian American man who was convicted of assassinating Robert Kennedy in 1968. I think I heard you wrestling with that part of Abdeen's activism, his legal defense of this person who's committed this violent act.

Kai Wright: Yes.

Suzanne Gaber: Can you tell me a little bit about what was bothering you?

Kai Wright: I guess it's not the fact of somebody serving as a defense attorney for an accused assassin, just to be clear about that. I admire that choice and believe everybody's got to have proper defense when the government decides to come for you. It's really the specific questions around Palestinians. I struggle with any and all forms of political violence, Suzanne. I just instinctively recoil from it. I think a lot of people feel the same way. I think we have to be honest that that's been a real challenge for the Palestinian Liberation Movement in the US, that people associate it with violence, rightly or wrongly, because of the factions that do believe in armed resistance. That's not at all what Abdeen is talking about with Sirhan Sirhan. He's talking about trauma. I get that. Still, I just flinch at any connection between the ideas he's advocating for and acts of violence.

Suzanne Gaber: Yes. I've got to be honest about this part that's hard for me as well, because it gets at a lot of the stereotypes that I and a lot of Arab Americans have tried to move away from. The idea of Arabs being associated with violence. A lot of that violence is really hard to stomach. I think what's important here is that for people, like Abdeen, part of creating a deeper understanding of what Palestinians have been through and Arabs more broadly when we get into later wars, means understanding the roots of that violence.

Kai Wright: Yes.

Suzanne Gaber: I think when we talk about some of these very intense cases Abdeen has worked on, that's something to remember.

Kai Wright: Right. That's maybe even more challenging of a principle to hold when we talk about another intense case in American history where Abdeen stepped in. In 1995, Omar Abdel Rahman, popularly known as the Blind Sheikh, was convicted of attempting to blow up several landmarks in New York City. Abdeen helped his defense team, and he says it taught him something important, even if he wasn't actually looking to get involved in the case in the first place.

Abdeen Jabara: I got involved in that case almost by happenstance. I did not seek it, but I was contacted by Attorney Ramsey Clark. He called me, and he wanted me to come because some of the Sheikh's supporters had come and asked him to represent the Sheikh. He wanted me to come to help him find somebody to do that. We talked to several different people. Finally, it was Ramsey that came up with contacting Lynn Stewart. He asked me if I would help her, and I said, "Yes, I'll help her." I was not in any way, shape or form a lead attorney for the Sheikh, but I did quite a bit of work on it. Of course, I met with him on a number of occasions.

I had a feeling about this whole terrorism issue that is probably different from what many Americans think. I think that the United States creates terrorism in many instances, and cannot always be held blameless. I thought that was the case in the Sheikh's case, because that all grew out of Afghanistan, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and then the Americans recruiting the Mujahideen. All these Islamists to go fight the Russians. The Saudis were paying the bill on this. These Islamists, they did not think America was their friend, because they saw America propping up all these governments in the Middle East that were not representing the people. These attacks from these Muslims on the United States, it was stupid. I don't, in any way, shape, or form, support them, but I understand them.

Is that reasonable that I don't support him, but understand him?

Kai Wright: Culturally, tell me if this is true, but it seems to me in my lifetime, one of the reasons that it has been difficult to get people to think about Arab American rights and Palestinian rights in particular is this cultural association between the words Arab and terrorists.

Abdeen Jabara: Yes, of course. They think of Arabs and terror, and they use them synonymously. We had a hell of a time, oh my goodness, with dolls and Halloween masks, and these cartoons, and films from Hollywood. There was just a massive number anti-Arab films from coming out of Hollywood. Cartoons in the newspaper.

Kai Wright: I grew up on it.

Abdeen Jabara: Yes. Of course you would've.

Kai Wright: I just grew up on it. Every villain was Arab.

Abdeen Jabara: What about Native Americans? Do you remember that? When we were kids, I had all these cowboy and Indian movies. You remember?

Kai Wright: I grew up in the '80s. By then, absolutely, Arabs were the Indians —

Abdeen Jabara: Absolutely.

Kai Wright: of the Cowboys and Indians of action films.

Abdeen Jabara: That was intentional. It was not an accident, because it was part of creating this whole mindset about the Arabs are the bad guys. We were able to do a lot to alleviate that by different campaigns and so forth, but still that exists because they don't-- Americans, it's this whole business about they want peace, but they don't think about justice. If they thought about the two words in the same mindset, they wouldn't associate Arabs with terrorism.

Kai Wright: We asked our followers on Instagram to send us questions for you, since we're normally a live call in show, and one of our listeners, Ryan in Virginia, asked if you could imagine a point where either major party would take up Palestinian liberation as a plank.

Abdeen Jabara: There's been a huge thing, and I call it an American intifada, and it's the result of the Gaza genocide, and the result of social media. Those two things, the major mainstream media can no longer control the narrative. There's all this other information that's coming out on the internet from international news and from what's happening in the third world. The government can't constrain it as much as they try. They get these university presidents and kick them out of office because they don't do enough to quell the uprising by the students, but the students will not stay silent.

Kai Wright: Were you surprised by that? By the level of the response?

Abdeen Jabara: I was flabbergasted, and I was so absolutely thrilled that after all these years of trying to do something, that now we had a mass movement in this country for Palestinian rights.

Kai Wright: Had we seen such a thing before?

Abdeen Jabara: No, absolutely not. This is totally a totally new phenomenon. I'm so pleased by these young people today. Oh my God, I can't tell you. I live in New York. We have demonstrations, every single week there's a demonstration. They'll block this and block that and take over this. It's just marvelous. They're not Arabs. Some of them are Arabs. Some of them are Arabs, but a lot of them are just young people with a conscience. I'm just totally thrilled by it.

Kai Wright: You credit that to just the change in who has the microphone?

Abdeen Jabara: Yes. That and the work that we did over the years, the literature and the this and the that. It was not very much, but it helped create some kind of space. I didn't move things as much as I would've liked, but I can't say that what I did was useless. It's hard to reminisce about all this stuff because it brings up all these things that you don't think about on a daily basis and about how this is related to that and so forth.

Suzanne Gaber: Kai, hearing him talk about the new generation and watching the modern movement for Palestinian rights, I couldn't help but picture Abdeen in his apartment with his own kids watching the news of a place he loves so much being destroyed, and how similar the image was to the moments of his dad hunching over the radio back in 1948.

Have you thought about that, listening to everything that's happening in Gaza right now?

Abdeen Jabara: Oh my God, it's just hard to talk about Gaza. It's so painful. I'm sorry. Sorry. I didn't think I-- Gaza is terrible. I never thought I'd cry. I haven't cried since Gaza started, but just talking about all this stuff now is very-- Gaza, it's just a horrible thing. It's just hard to believe that, and I blame this country as much as the Israelis, 100%. I don't know what we're going to do about it. I hope these young people do, but I turned the baton over to them.

Kai Wright: Another listener who sounds like maybe they've picked up your baton, is Engy in New York, and they asked, as someone who has been through years of surveillance, how can a person protect their privacy in a surveillance state?

Abdeen Jabara: Good question. It's not easy. The first thing I think a person has to do is work in coalition. I encourage people that they have to, number one, get support from wherever they can find it and help build a united front. There are a number of organizations like the National Lawyers Guild, that are out there day in and day out. They have a program now, a legal observer program. They go to all these demonstrations to make sure that the police do not mishandle the demonstrators, and that there is no violation of their rights. The National Lawyers Guild has limited resources in terms of actually representing people, but there are individual attorneys on there that do absolutely incredible work.

Kai Wright: There is a potential new Trump administration coming. A lot of people are deeply concerned about what that would mean for things like surveillance of activists, particularly people who are protesting for the rights of Palestinians, what it might mean for beyond surveillance. Are you concerned about that?

Abdeen Jabara: There'll be a lot more deportation. There'll be a lot more deportation if Trump gets in. I don't know whether he'll have the Muslim ban. I don't think he's going to reinstitute the Muslim ban, but he did. He had that, five countries, people from those countries were no — by the way, I want to go back one moment just to say one thing about this Operation Boulder that I forgot to mention.

Part of Operation Boulder was that every Arabic surname individual, regardless of their nationality, whether they came from Latin America, or Central America, or Europe, every Arabic surname individual had to be screened by the American intelligence community in Washington before being granted an entry visa to United States. That lasted for several years, and then they abandoned it because it wasn't useful, but that talk about racism, that is the core thing of Operation Boulder.

Kai Wright: One more question from a listener. How do organizations and movements make space for national identities within the larger framing of Arab American groups?

Abdeen Jabara: The one thing that we did in creating these national organizations is that we wanted to tear down these barriers. Our second president of the AUUG was Egyptian. Our first president was Lebanese, Christian. The third president was a Palestinian. The fourth president, me, was an American born of Lebanese background whose family was Muslim. It was this whole thing.

Kai Wright: Do you think now the community has succeeded and matured, whatever is the right word, to the place where there is truly an Arab American?

Abdeen Jabara: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. There's an Arab American identity now, and it manifests itself by what happened in Michigan in the primaries. I was so happy. I sent flowers to the mayor of Dearborn thanking him for his leadership. It's wonderful.

Kai Wright: Having witnessed all that you have, and having witnessed this new mass movement over the last year, how do you see the next five years?

Abdeen Jabara: I'm optimistic. I'll tell you. I tell people, they ask me, "How do you keep going?" I'm much more disengaged now, but I tell them that you can't do political work and not be optimistic. It's just not possible because otherwise, you can't do anything. If you're not optimistic that change is possible, then you shouldn't do anything. Just lean back and watch the world go by. I think we have the idea that change is possible, that justice is possible, but it's only going to happen if there's a mass movement to make it happen, and that's what we're seeing now.

Kai Wright: Abdeen Jabara is now 83 years old working on his memoir and going through his papers at the University of Michigan. He's been a legal activist and civil rights organizer in Arab American communities since the 1960s.

Notes From America is a production of WNYC studios. Follow us wherever you get podcasts, and look out for our new weekly bonus episode on the 2024 election. There's just too much to cover. I've got too many questions for one show a week, so we're going to be popping into your podcast feed every Thursday morning between now and election day. The first one's there for you right now. It's a conversation with CNN's national politics correspondent, Eva McKend, who's on the campaign trail with Kamala Harris. Just hours after Joe Biden turned his campaign over to the Vice President, 44,000 Black women convened a Zoom call to process the news. Eva was on that call. She talks to me about what went down and about what she's seeing in the opening days of the Harris for President campaign tour.

Also, look for us on Instagram. Our handle is NoteswithKai. That's where we often ask you questions that shape our shows. Do check us out. This episode was produced by Suzanne Gaber. Our theme music and sound design is by Jared Paul. Our team also includes Katerina Barton, Regina de Heer, Karen Frillmann, Matthew Morando, Siona Petros, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. I'm Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us.

[MUSIC]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.