Humanity's Temporal Range

( Nadim Silverman / WNYC Studios )

Hi, John Green here with a cold open. So I wrote and recorded this review several weeks ago, before the global Covid-19 pandemic began closing schools, reshaping daily life, and threatening the health and wellbeing of so many people. The always unpredictable future now feels truly terrifying in its uncertainty, and I'm left feeling, to borrow a line from the poet Paige Lewis, all stopped up with dread. So much has changed since I wrote this review, and there are parts of it that I now find eerie and disconcerting, but so it goes. Despite the ridiculously lofty name of the anthropocene reviewed, I've always wanted the podcast to be what I think reviews always are, a kind of memoir--one person's experience of the beauty and horror and surreality of contemporary life. So I guess this episode is about how it felt to imagine looking over the edge--before I realized how close we always are to the edge.

Amid this crisis I see much to fear an lament, of course, but I also see humans working together to share and distribute what we collectively learn. And I see people working together to care for the sick and vulnerable. Even separated, we are together. And this is not the end of us. Not anywhere close. One thing that hasn't changed since I wrote this review: I still believe in the human endeavor. Now more than ever, really. Alright, here's the show.

Hello and welcome to The Anthropocene Reviewed, a podcast where we review different facets of the human-centered planet on a five-star scale. I’m John Green, and today I’ll be reviewing the concept of humanity’s temporal range.

When I was in college, my favorite phrase was “eschatological anxiety.” I liked the way it sounded, but I also liked the way it made me sound. In those days, I wanted so desperately to seem smart and promising and successful and just the right amount of tortured. In fact, I wanted to seem successful and smart much more than I wanted to be successful or smart. I like to think I’ve been cured of that disease, but then again, I like to think a lot of things that aren’t true.

To be fair to my collegiate self, I used the phrase eschatological anxiety, which means worry about the end of the world, in part because I felt it so often. This was the late 90s, when the Y2K computer bug was about to absolutely destroy human society. The worry was that because many computer programs only had two digits for the year instead of four digits, rolling over to the year 2000 would be catastrophic. I wasn’t alone in this fear. A U.S. senator, Pat Moynihan, said, “I have no proof that the sun is about to rise on the apocalyptic millennium of which chapter 20 of the Book of Revelations speaks. Yet, it is becoming apparent to all of us that a once seemingly innocuous computer glitch related to how computers recognize dates could wreak worldwide havoc.” You can forgive a kid for feeling a bit of eschatological anxiety.

I spent December 31st of 1999 with my girlfriend. We were in Orlando, Florida--an ideal location for witnessing the end of humanity. And I remember watching the fireworks from Lake Eola Park and waiting for the world’s lights to go out. But nothing happened, and I thought back to something my religion professor Donald Rogan had told me once: Never predict the end of the world. You’re almost certain to be wrong, and if you’re right, no one will be around to congratulate you.

When I was nine or ten, I saw this planetarium show at the Orlando Science Center in which our host, with no apparent emotion in his voice, explained that in about a billion years, the sun will be 10% more luminescent than it is now, likely resulting in the runaway evaporation of Earth’s oceans. In about four billion years, the Earth’s surface will become so hot that it will melt, and then in seven or eight billion years, the Sun will be a Red Giant star, and as the Sun expands, our planet will eventually be sucked into it, and any remaining Earthly evidence of what we thought or said or did will be absorbed into a burning sphere of plasma. Thanks for visiting the Orlando Science Center. The exit is to your left.

It’s taken me most of the last 35 years to recover from that presentation. I would later learn that many of the stars we see in the sky are red giants, including Arcturus. Red giants are quite common. It is common for stars to grow larger and engulf their once-habitable solar systems. No wonder we worry about the end of the world. Worlds end all the damned time.

A 2012 study conducted in twenty countries found wide variance in the percentage of people who believe humanity will end within their lifetimes. Like, In France, six percent of those polled did; in the United States, 22%. And this makes a kind of sense; France has been home to apocalyptic preachers--the bishop Martin of Tours, for instance, wrote “There is no doubt that the Antichrist has already been born” and was confident the world was about to end, but that was back in the fourth century. American apocalypticism has a much more recent history, from Shaker predictions the world would end in 1794 to famed radio evangelist Harold Camping’s calculations that the apocalypse was coming in 1994, and then, when that didn’t happen, in 1995. Camping went on to announce that the End Times would definitely commence on May 21st, 2011, after which would come “five months of fire, brimstone and plagues on Earth, with millions of people dying each day, culminating on October 21st, 2011 with the final destruction of the world.” When none of this came to pass, Camping said, “We humbly acknowledge that we were wrong about the timing,” although for the record no individual every humbly acknowledged anything while referring to themselves as “we.”

Camping’s personal apocalypse arrived just a couple years later, when he died in 2013 at the age of 92. And part of our fears about the world ending must stem from the strange reality that for each of us our world will end, and soon. In that sense, maybe apocalyptic anxieties are mostly a byproduct of humanity’s astonishing capacity for narcissism. How could the world possibly survive the death of its single most important inhabitant--me? But I think something else is at work, too, something involving humanity’s astonishing capacity for understanding the past and imagining the future.

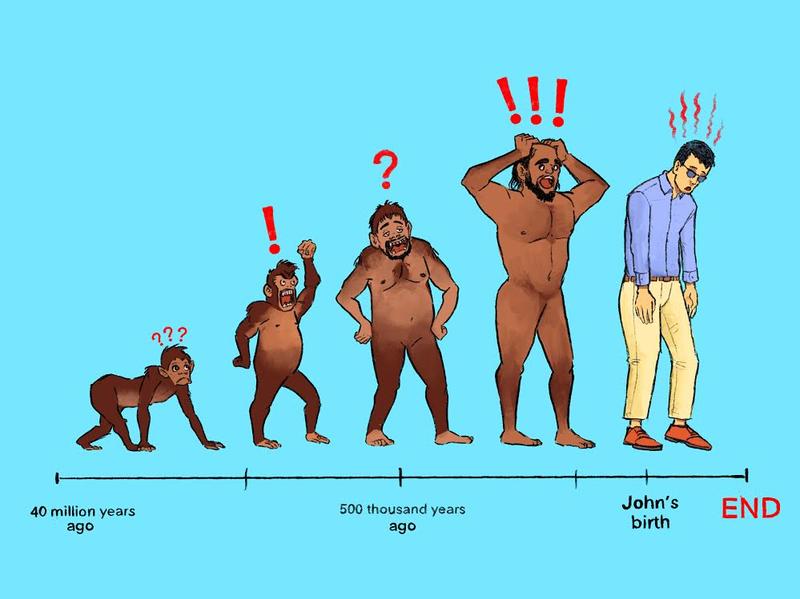

“Modern humans,” as we are called by paleontologists, have been around for about 250,000 years. This is our so-called “temporal range,” the range of time we’ve been a species. Contemporary elephants are at least ten times older than us--their temporal range extends back to the Pliocene Epoch, which ended over 2.5 million years ago. Alpacas have been around for something like 10 million years--forty times longer than us. And tuatara, a species of reptile that lives in New Zealand, has been around for about 240 million years, a thousand times longer than we have, since before Earth’s supercontinent of Pangea began to break apart.

We are younger than polar bears or coyotes or blue whales or camels. But are we the period at the end of the very long sentence of Earth life, or a comma somewhere in the middle of that sentence?

We’ll turn our attention to that after the break. But first, to borrow a line from a Mountain Goats song, here’s an opportunity to fight the creeping sense of dread with temporal things.

AD BREAK

One rule of retail marketing holds that to maximize sales, businesses need to create a sense of urgency. Mega-sale ends soon. Only a few tickets still available. Get your anthropocene reviewed coffee mugs, which contain a review of coffee mugs, before they sell out at dftba.com. Of course, if they do sell out, we’ll order more. This sense of urgency, especially in the age of e-commerce, is almost always a fiction. But it does motivate people to buy coffee mugs, and also to do much else. And maybe that’s also part of our apocalyptic visions--if we feel a sense of urgency about the human experiment, maybe we’ll actually get to work, whether that’s rushing to save souls before the rapture or rushing to address climate change.

I try to remind myself that back in the fourth century, Martin of Tours’ eschatological anxiety must have felt as real to him as my current anxiety feels to me. But there is a difference between Martin of Tours’ worry and my own: All apocalypses are possible, I guess, but the climate change catastrophe is in progress. Average global temperatures have already risen a degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and we know from the fossil record that sudden changes in global temperature are often calamitous. We don’t feel near the level of urgency that’s appropriate, even though climate scientists speaking with a unified voice have been saying Big Sale Ends Soon Must Act Now for decades.

The truth is, humans are already an ecological catastrophe--in just 250,000 years, our behavior has led to the extinction of many many species, and driven many more into steep decline. This is lamentable, but it is also increasingly needless. We probably didn’t know what we were doing tens of thousands of years ago, when humans likely hunted many species of large mammals to extinction. But we know what we’re doing now. We know how to tread more lightly upon the Earth. We could choose to use less energy, eat less meat, clear fewer forests. And we choose not to. And as a result, for many forms of life, humanity is the apocalypse.

I find it interesting that when we talk about the end of humanity, we so commonly refer to it as “the end of the world.” There are many worldviews that embrace cyclic cosmologies--Hindu eschatology, for instance, lays out a series of multi-billion-year periods called kalpas during which the world goes through a series of formation, maintenance, and then decline. But in linear eschatologies, the endtimes for humanity are often referred to as “the end of the world,” even though our departure from the Earth will very probably not be the end of the world, or the end of life in the world.

Sixty five million years ago, an asteroid impact caused a dust cloud so huge that darkness may have pervaded the Earth for two years, virtually stopping photosynthesis and leading to the extinction of seventy five percent of land animals. We’re just not that important. When Earth is done with us, it’ll be like, “Well, that was weird, but at least I didn’t get large asteroid syndrome.”

The hard part of life, evolutionarily, was getting from prokaryotic cells to eukaryotic ones, and then getting from single-celled organisms to multicellular ones. Like, if you imagine the 4.5 billionish year history of Earth as a single 24-hour day, Earth formed at midnight. The moon was formed by a huge impact with another planet around 12:10 AM. The first single-celled life appeared around 4 in the morning. It’s not until 1 PM that the first eukaryotic cell appears, when one cell swallowed another and the two manage to form a symbiotic relationship that eventually allowed for cells to have nuclei, mitochondria, and so on.

Multicellular life appears around 6 PM. Just before 9 PM, the first jellyfish come along, as do early vertebrates and many other creatures during the so-called Cambrian Explosion. Plants start growing on land at 9:52 PM. Dinosaurs go extinct at 11:41 PM. And then a few seconds before 11:59 at night, humans show up.

The reason I still remember that long-ago visit to the Orlando Science Center is because I haven’t been able to forget that our species had a beginning and will have an end. We are different from other animals in important ways, but in the fundamental way we are the same: We all have a temporal range. There is a gravestone out there that reads Humans. 248,000 BCE and then there is a dash, and then there is a blank space.

I know the world will survive us--and in some ways it will be more alive. More birdsong. More creatures roaming around. More plants cracking through our pavement, rewilding the planet we terraformed. I imagine coyotes sleeping in the ruins of the homes we built. I imagine our plastic still washing up on beaches hundreds of years after the last of us is gone. I imagine that moths, having no artificial lights toward which to fly, will have to turn back toward the moon.

And so I know it won’t all be bad news. There is some comfort for me in knowing that life will go on even if we don’t. But I would argue that when our light goes out, it will be the Earth’s greatest tragedy, because while I know we are prone to narcissism and grandiosity, I also think we are by far the most interesting thing that ever happened on Earth.

I believe that if a tree falls in the woods and no one is there to hear it, it does make a sound--but if no one is around to play Billie Holiday records, then those songs really won’t make a sound anymore. I know we’ve caused a lot of suffering, but we’ve also caused much else.

It’s easy to forget how wondrous you are, how strange and lovely. Through photography and art, you’ve seen things you’ll never see--the surface of Mars, the bioluminescent fish of the deep ocean, a seventeenth century girl with a pearl earring. Through empathy, you’ve felt things you’ll never feel. Through the rich world of your imagination, you’ve seen apocalypses large and small.

I mean, we’re the only part of the known universe that knows it’s in a universe. We know we are circling a star that will one day engulf us. We’re the only species that knows it has a temporal range.

We are also the planet’s best chance by far of exporting complex life to other places in the solar system, or maybe even beyond the solar system. For any of that to happen, of course, our temporal range will need to extend beyond the next few thousand years. We’ll have to find a way to survive, ourselves--to survive in a world where we are powerful enough to warm the entire planet but not powerful enough to stop warming it. We’ll have to learn to better value life, not just human life, but biodiversity more generally. And we may have to survive our own obsolescence as technology learns to do more of what we can do better than we can do it.

Of course, our odds are poor. Complex organisms tend to have shorter temporal ranges than simple ones, and humanity faces tremendous challenges. On the other hand, we have more collective brainpower than we’ve ever had, and more resources, and more knowledge collected by our ancestors.

We are also shockingly, stupidly persistent. Like, early humans probably used many strategies for hunting and fishing, but a common one was persistence hunting. In a persistence hunt, the predator relies on tracking prowess and sheer perseverance. We would track prey for hours, and each time it would run away from us, we’d follow it, and it would run away again, and we’d follow it, and it would run away again, until finally the quarry became too exhausted to continue, and that’s how for tens of thousands of years, we’ve been eating creatures faster and stronger than us. We. Just. Keep. Going.

We spread across seven continents, including one that is entirely too cold for us. We sailed across oceans toward land we could not see and could not have known we would find. That moon that formed at 12:10 in the Earthday morning? We went there, too. One of my favorite words is dogged. I love dogged pursuits, and dogged efforts, and dogged determination. Now don’t get me wrong--dogs are indeed very dogged. But they ought to call it humaned. Humaned determination.

For most of my life, I’ve believed that we are in the fourth quarter of human history, and perhaps even the last days of it. But now, I’ve come to believe that such despair only worsens our already slim chances. We must fight like there is something to fight for, like we are something worth fighting for, because we are. And so I choose to believe now that we are not approaching the apocalypse, that the end is not coming, and that we will find a way to survive the coming changes.

“Change,” Octavia Butler wrote, “is the one unavoidable, irresistible, ongoing reality of the universe.”

These days, I choose to believe that our persistence and our adaptability will allow us to keep changing with that universe for a very, very long time.

And, so in hope, and in expectation, I give humanity’s temporal range five stars.

Thanks for listening to The Anthropocene Reviewed, which was written by me, edited by Stan Muller, and produced by Rosianna Halse Rojas and Jenny Lawton. Joe Plourde is our technical director, and Hannis Brown makes the music. This episode of the podcast was inspired by the many of you who’ve written me at anthropocenereviewed at gmail dot come to share your worry over humans and our place in the universe. I share that worry, and all I can say in response to it is that we are in the very fortunate position of having at least some say in whether humanity has a future, and what that future looks like. Thanks again for listening, and for being here with us.