Episode 3: We’ll Always Have Paysandu

Roger Bennett: Okay, I'm going to take you back to 1995. It's the beginning of July, 22 soccer players are on a plane.

Eric Wynalda: Just with all your buddies scattered out in middle seats and stuff and once again, not being in first class.

Roger Bennett: That's right, the US national team, America's elite soccer force, they fly coach. They're on the way to an international tournament in South America and the flights are long.

Eric Wynalda: Six hours into the flight, that's when we got the piece of paper.

Roger Bennett: The paper, it's dropped onto one of the sleeping players' laps in the middle of the night.

Eric Wynalda: The light starts turning on over the middle seats.

Roger Bennett: Drowsy soccer players stir awake, they stretch their arms, rub their eyes, unfold the paper and read it. Guys coming over the top of their seats everywhere, asking each other, "Have you seen this?"

Eric Wynalda: "Have you seen what they've just offered?" I was asleep, I said, "No."

Roger Bennett: Now, in soccer, there's an old coaching cliche, nothing in the game travels faster than the ball. That piece of paper though, it was an exception to the rule.

[music]

Roger Bennett: This is American Fiasco, a show set in a time when frequent flyer miles still meant something and a big ass carry on bag was a God given right. I'm Roger Bennett. I want to take you back a couple of hours earlier before the flight at the Miami International Airport. The 22 players are boarding the plane, they've been invited to compete in a huge tournament in Uruguay, the Copa America, where they'll face some of the best teams in the world.

One problem, there haven't been time to finish negotiating their contracts in advance of the flight because let's be real, soccer players, they live to play the game, not to negotiate it. Just a few weeks before, these same players had beaten Mexico in a shutout game, not even their greatest fan could have predicted, they were flying high. The 1994 World Cup, had meant money was pouring into US Soccer for the first time and these players, they assumed they'd get a piece of it and then came that sheet of paper.

Eric Wynalda: That simply stated if you had not played for the national team up to 10 caps you would not be compensated whatsoever for your inclusion in this competition.

Roger Bennett: All right. Eric Wynalda just used a soccer term there, caps. That's just the stat that counts how many times a national team player has appeared in an international match. That sheet of paper was an offer from US Soccer, a plan to compensate players on a kind of sliding scale. Players who have a lot of caps, they could receive as much as $5,000, players with just a few, they get nothing.

Eric Wynalda: What that means is, is there was divide and conquer, it was, "Let's get the veteran players to comply and screw everybody else."

Roger Bennett: Even though the offer would benefit Wynalda and the other veterans, they knew it would go against the very thing that had made them successful.

Eric Wynalda: It was about being a team and we, for the first time, felt like we had an identity, we felt like we were a team that could do great things. That was always our mindset. Not that, "Okay, we deserve better than this." It was, "Hey, why are you trying to manipulate us? Why are you trying to fragment us? Why do you pull us apart?"

Roger Bennett: What was the federation thinking? Ask yourself, what would you do in 1995 when you find yourself at a tense negotiation standoff with your boss 40,000 feet below you? Eric Wynalda again.

Eric Wynalda: We called the meeting of the back of that plane.

Roger Bennett: America's best soccer players are congregating in the bathroom [unintelligible 00:04:17]

Eric Wynalda: Pretty much. We actually had asked some people to move out of their seats, you can imagine if you can visualize this, all of us in the back right part of the plane.

Roger Bennett: Yes Wynaldaa, I've seen the back of an airplane, but what I've never seen is the entire US Soccer Team calling a huddle in one.

Eric Wynalda: It was everybody, even guys that had never really had any time with the national team, the whole group. "Who's not here?" I remember saying that out loud, "Who's not here? Eight of us can't solve this, all of us solve this. Until this is resolved, we will not practice, we will not play. That is the decision that's been made by the team."

Roger Bennett: We're going on strike.

Eric Wynalda: Yes.

[music]

Roger Bennett: The Copa America, that's a tournament held every two years between every single national team in South America plus a few invited guests. In 1995, it was taking place in Uruguay, four Uruguayan cities, including one called Paysandu. I looked up Paysandú on the Wikipedia page, let's be real, it's the only way anyone learns anything about a place they've never been. If you look under the notable persons heading, you'll find three local politicians, a band called Los Iracundos from the '60s who's biggest hit was this song.

[music]

Roger Bennett: You'll also find no fewer than five Uruguayan football players. Uruguay itself is a relatively tiny country, jammed in there between Brazil and Argentina with a population smaller than Los Angeles. Its economy revolves around beef and wool and tourism but football, football has always been its favorite export. That Uruguayan love of soccer, it's matched only by one thing, the degree to which they hate their arch-rival, Argentina.

This is a rivalry that stretches way back to the 1880s when Uruguay beat Argentina in the first-ever world cup final in 1930, the Uruguayans declared the day to be a national holiday while in Buenos Aires, there were riots across the city. Into this age-old rivalry, strode the US soccer team who were slated to play Argentina in the third game of the Copa, making the Americans instant VIPs across Paysandu. This team that was on the verge of striking had only pulled into the one place in the world that was most excited to see them play

Translator: It was really incredible how the American team was received by folks in Paysandú.

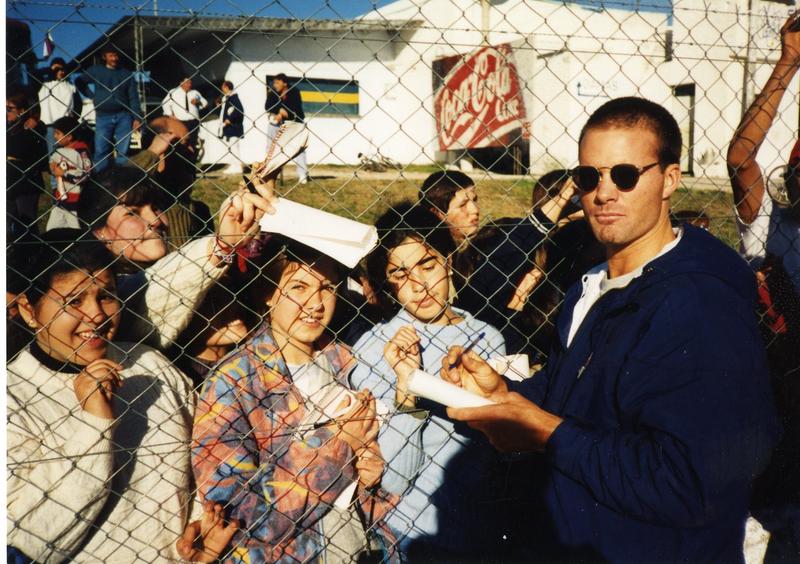

Roger Bennett: I reached Pedro Dutore by phone, he's a sports journalist for Paysandu's leading newspaper, El Telegrafo. But back in 1995, he was just a 16-year-old kid who bought a ticket to every Copa America match being played in his town and on the day the Americans arrived, Pedro and his friends only wanted to do one thing, go and find them

Translator: We were like, "Let's go wait for them at the hotel." One of my buddies wanted to go up and say hi to Alexi Lalas

Roger Bennett: In Paysandu, Jim Froslid, the team's 28-year-old press officer, glimpsed for the first time the global power of the 94 world cup.

Jim Froslid: We were walking down this really rickety street, very underserved area, and in between these two buildings is this little alley and there was this little kid sitting there. I'm with Alexi and this kid looks up at him and his face just lights up and he goes, "Lala." I'm like, "Holy smokes, he knows who you are."

Roger Bennett: The team checked into the Hotel Bulevar, a modest budget type of place. Alexi Lalas remembers its most distinguishing feature.

Alexi Lalas: This partition of glass was all across the front, it was this fishbowl type of existence because the locals they had never seen a US team and the public wasn't allowed in the hotel but they were allowed right up to the glass.

Roger Bennett: They got quite a reality show.

Alexi Lalas: We played a lot of back cabin and we drank a lot of cappuccinos in that lobby.

Roger Bennett: Because of the strike, the Uruguayan fans weren't getting to see the Americans play, but they got plenty of time to watch them not play.

Alexi Lalas: They would press their faces up to try to get a glimpse of the American players while we sat there, it was almost like a museum exhibition, "Come see the Americans." [laughs]

Roger Bennett: Come watch the Americans drink coffee, come watch the Americans formulate their next steps in the negotiation strategy. By now the players have developed a list of demands that really all boiled down to one thing, more money and they wanted that money distributed equally. The players told the US Soccer Federation that they wouldn't so much as lift a cleat or toe, unless these demands were met.

Alexi Lalas: We would all pile into our rooms which were like two beds a room, little cots.

Eric Wynalda: A room the size of a bathroom that we've managed to cram all 23 players in.

Roger Bennett: From there they'd send off faxes to US Soccer back in Chicago and then they'd wait.

Eric Wynalda: Where do we stand, did the last fax come through? Have we agreed terms? Can we go and train now?

Roger Bennett: Back in Chicago, federation general secretary, Hank Steinbrecher also wanted the players to get back into training but he saw the negotiation differently.

Hank Steinbrecher: I'm looking at saying, "Well, we've done an awful lot. This is what we think is a fair and legitimate deal." They come back with all these visions of grandeur saying, "No, you're not paying us enough. You guys are screwing us." So I was disappointed.

Roger Bennett: The way Steinbrecher saw it, US Soccer had invested so much in these players and their development for years. Remember, before 1994, the idea of even being able to make a living playing professional soccer in America, that was impossible.

Hank Steinbrecher: Who put you in a housing complex to have a professional team without a professional league? The federation with little resources cared enough to help develop you and now you're going to hold us up for extra money. You don't want to play for the United States National Team, you don't want be [unintelligible 00:10:48], you ungrateful lot.

Roger Bennett: More faxes from the hotel.

Eric Wynalda: You're supposed to be our partners in this.

Alexi Lalas: I remember moments where we were in a room together as a team and we said, "Look, are we going to fight this? Are we not going to fight this?"

Roger Bennett: What? Consensus is cracking. Hold it together, lads.

Eric Wynalda: You can see a few guys were hesitant but we made it very clear that in order for this to happen, it's got to be united.

Roger Bennett: Then a fax from the federation.

[beep]

Hank Steinbrecher: You're going to put a noose over our neck and a bullet to our head? Screw you. You're finding your way home and I'm bringing down the Olympic team.

Roger Bennett: What? The Olympic team. Steinbrecher didn't just threaten to send in replacement players, did he? Scabs.

Hank Steinbrecher: Sure did.

Roger Bennett: The players responded in kind.

Alexi Lalas: Great. Go for it.

Roger Bennett: They called his bluff. Back at the hotel Bulevar, there were Uruguayan soccer fans where their noses pressed against the glass just to glimpse Marcelo Balboa, Alexi Lalas and Eric Wynalda sip coffee. There was no way Hank Steinbrecher was going to send in the scabs and replace these big names to represent the United States in the biggest tournament in South America.

Hank Steinbrecher: Yes, I absolutely would have done it.

Roger Bennett: But you didn't do it, Hank Steinbrecher, you blinked.

Hank Steinbrecher: We came to a compromised position which was not a popular decision by the way, because the members of our board, there's no way you're going to give in to these guys. Give in to them now, you'll be giving in to them forever.

Roger Bennett: Reluctantly, US Soccer agreed to increase the player's fees. On the morning of July, 7th, 1995, the day before the first game of the Copa against Chile, Coach Steve Sampson finally got his team back.

Steve Sampson: The thing is that when you ask for more money, you better live up to it. You better go out and prove that you deserve that money.

Roger Bennett: Steve rounded up Lalas and his teammates who had time for just one practice before the first game.

Alexi Lalas: I'll never forget him looking at us and saying, "All right, you fuckers, you got what you wanted. Now you do your job."

[music]

Commentator: [foreign language]

Roger Bennett: This is American Fiasco. I'm Roger Bennett.

[background noise]

Roger Bennett: That's the sound of Eric Wynalda opening the scoring in the US's first game of the Copa. The striker celebrated first with his teammates but then after spotting US Soccer officials sitting in the stands, he charged towards them pointing his finger in accusation. You ran screaming.

Eric Wynalda: Yes.

Roger Bennett: You're screaming at US Soccer?

Eric Wynalda: That was my moment to remind them that, "Don't be the enemy. We're in this together."

Roger Bennett: Six minutes later, Wynalda scored again with a dream strike of a free-kick from long range that curled past the goalkeeper's flailing fingertips.

Commentator: [foreign language].

Roger Bennett: Just like that, the Americans have won their first game, 2-1 against Chile. To this day, I'd still love to know what was in that coffee they serve at the Hotel Bulevar because this was the first time the US had beaten a South American team on South American soil since the inaugural World Cup back in 1930. By now, the Uruguayan fans were waiting in droves around the Hotel Bulevar.

Jim Froslid: Everything was police escorts. Jim Froslid, the press officer. When you have one of those, it's an amazing feeling. Now, here you are slicing through traffic and the fans were crazy for these US players.

Roger Bennett: Why do you think?

Jim Froslid: Americans have this confidence, and it's what pulls us through.

Roger Bennett: Where does the confidence come from, Jim?

Jim Froslid: I think it's patriotism. It's the 1980 Olympic hockey team. It's achieving things that you really have no business achieving.

Roger Bennett: The American's next game was a reality check. A 1-0 loss to Bolivia. For the people of Paysandu, all that mattered was what comes next. These upstart Americans were set to play the team despised by Paysandu and all of Uruguay. I'm speaking of course of Argentina. A quick word on the Argentine playing style because it's singular. It's as brutal as it is beautiful, ferocious and dirty, poetic and pure. Their fans, they expect their players to drive at their opponents, beguiling them, weaving, dribbling, swallowing. If an opponents groin or kidney presents itself somewhere along the way, they also expect them to deliver a thunderous punch.

The most legendary Argentine player of all time was a midfielder named Diego Maradona. I carry my own scars caused by the memory of Maradona. He's the man who vanquished my beloved English squad 2-1 in the 1986 World Cup.

[background cheering]

Roger Bennett: The first goal from a move that became known around the world as the Hand of God and only in England as a Hand of the Devil. Picture this, a five-foot five-inch tall Maradona leaping to use his left fist to reach over a dumbfounded English six-foot goalkeeper and punch the ball into the net so quickly the referee didn't even see it.

Commentator 1: The goal is given. At what point was he offside or was it a use of the hand that England are complaining about?

Roger Bennett: Such brazen impudence, but four minutes later, Maradona's dirty trick was followed by an act of sheer brilliance. He got the ball and charged 60 yards dancing blindly through the entire English team to score again.

[background noise]

Roger Bennett: By the time the Copa rolled into Paysandu in 1995, Maradona's international career was over. He'd failed a drug test during the 1994 World Cup and was now forced to watch his team play from the stands. The 1995 Argentinians, the Copa's defending champions were no less fearsome. One of their star players was another Diego, Diego Simeone.

Eric Wynalda: This is a guy that was a bully on the field, and he was very good. He was a scary individual. A guy that you just don't mess with.

Roger Bennett: Back then, Simeone was the closest thing global soccer had to an NHL enforcer. Something Wynalda would have been well aware of but he was warming up with his team before the games and the tight confines of the hallway outside of the locker room. The Argentinians are in there to doing the same. A perfect opportunity for Simeone to let the dirty tricks begin.

Eric Wynalda: He starts belittling us.

Roger Bennett: In Spanish?

Eric Wynalda: Yes.

Roger Bennett: Give me in Spanish?

Eric Wynalda: Let's just put it this way. There was a couple of F-bombs and your mother would be involved.

Roger Bennett: The players on both sides keep stretching, skipping knees up high going back and forth and the next time Wynalda goes past Simeone.

Eric Wynalda: I told him, "I'm going to rip your face off."

Roger Bennett: Simeone barks something back in Spanish. They're trading insults.

Eric Wynalda: We met in the middle and I grabbed him.

Roger Bennett: You grabbed him by the-

Eric Wynalda: Throat and put him up against the wall. They had to pull us apart.

Roger Bennett: What made you do it? He was the most feared enforcer in the game? You're just an American guy. Nobody then knew who you were.

Eric Wynalda: This was about who we were aspiring to be. We're not afraid of anything. My dad said in the event that you get in a street fight, there's only one real rule to that. You hit first, you hit hard, and if that son of the bitch tries to get up, you don't let him.

Commentator: Jones loses control. A shot by Klopas, it's a goal. Frank Klopas scores and the US has taken the lead.

Roger Bennett: The United States hit first.

Commentator 2: This is going to be exactly what Steve Sampson was hoping for to happen.

Eric Wynalda: The message was to get forward and getting behind an attack and then press high at the field. Let's go out and make a statement for soccer in the United States.

Commentator: Without a doubt, one of the biggest goals in US history.

Eric Wynalda: We would have been really happy with the tie, quite frankly.

Roger Bennett: Of course these American players would have been happy with a tie. Like me, they've grown up watching the Diego Maradona era of Argentine football. When Alexi Lalas was 16, he'd watch the Argentinians win the 1986 world cup in person. Nine years later, he'd score a goal against them.

Commentator 2: They're actually trying to get out a favorable result.

Commentator 1: Wynalda curling it all the way to the far side. That's Cobi Jones. Cobi Jones, manned one on one, the cross into middle of the area. It's a goal, it's a goal. Lalas tucks it in inside the goal area. The US leads 2-0. Cobi Jones breaks out his man, sends the ball across--

Alexi Lalas: I knew that it was something that regardless of what happened, nobody will ever take away. I scored against Argentina.

Roger Bennett: Though normally a defender, he'd somewhat recklessly abandoned this position to make a bold dashing run towards the Argentine goal, and that gamble paid off. Diego Maradona himself would have been delighted with the way that Lalas didn't just score, but he scored with style. 15 minutes later, the halftime whistle went and the Argentines looked dazed as they shuffled to their locker room, hearing the boos from their own fans. The Americans were dazed too, but for a different reason. The locker room at half time, Alexi, are you going to tell me you were just cool, professional and of course, we were 2-0 ahead on Argentina, we United States of America?

Alexi Lalas: Well, there were certain moments where we kind of looked at each other and giggled.

Roger Bennett: In the second half, the Americans had to contain their giddiness. They needed a tie or a win remember, or they were out of the Copa. Argentina had been caught by surprise. They'd underestimated the Americans by resting their enforcer at Diego Simeone, but in the second half he entered the game. He almost scored twice, but almost doesn't count. Wynalda in on the other hand.

Commentator: But a little bit too far. Here's a chance, a goal, Wynalda. Joe-Max Moore pressuring and the ball comes free. Wynalda scores. It's 3-0, USA.

Translator: With the third goal, something automatic happening in all of us. We screamed.

Pedro Dutore: Goal.

Roger Bennett: That's Patrick Dutore, the same local teenager who greeted the Americans the day they arrived in Paysandu. He was there in the stands with his family, anxiously watching his beloved Americans. Even when they scored, he still didn't believe they had the chance to win.

Translator: It was not something we were planning. We kind of burst out on impulse. It was a goal scream from within, from deep inside.

Roger Bennett: The US then shut the game down, holding Argentina scoreless for the last half hour. The Americans had never dominated an opponent this powerful in quite this way. Alexi Lalas.

Alexi Lalas: I think it was affirmation and confirmation of, "You know what, whatever Steve is doing or whatever we're doing right now, it's working and let's not let this go and let's not screw this up."

Roger Bennett: Now, one more thing happened at this game, actually, after this game. It's an infamous story. In truth, every one of the players tells it a little differently. At this point, it's become a bona fide American soccer legend. Some say it happened in the locker room. Others say it happened outside the locker room in the hallway. Alexi Lalas swears it happened in a little bar inside the stadium, a cantina where a victory party was underway. Irrespective, there were many cold beers involved. Maybe because of them, the only thing everyone can agree on is that there was a lot of celebrating and they deserve to celebrate. They'd just beaten Argentina and then-

Alexi Lalas: The room just went quiet. It went kind of a hush.

Roger Bennett: Enter into the bar. It can't be. What? It's Diego Maradona.

Alexi Lalas: We all know he's one of the greatest, he's also a diminutive type of figure. It was just this partying of people as he came into the room, but you couldn't see him because he was so small.

Roger Bennett: He was small. A man once known around the world as El Pibe de Oro, the golden boy. It was he who made his way over to Lalas, Wynalda, and the other Americans.

Alexi Lalas: We all stood up. He walked to each one of us, individually shook our hand. In that moment, I think I recognized that my God, I was meeting a god. Through a translator he said, I'm not crying because he was.

Jim Froslid: Diego Maradona was and he started crying or he was crying.

Eric Wynalda: He started to tear up and he got upset. We were wondering what is going on here? His message was, I'm not crying because Argentina has lost, I'm crying because the Americans have played such beautiful football.

Roger Bennett: The US, they ended up placing fourth at the Copa, an achievement, which for the players, for Steve Samson, for the executives at US Soccer, if I'm going to be honest, it was genuinely astonishing. They journey to this hotbed of international soccer, they'd beaten a team that no one ever thought was touchable. They coaxed tears from a legitimate soccer god. Perhaps more than anything, they began to believe in themselves as true dark horses in the sport.

[music]

Eric Wynalda: I truly believe that we were headed in a direction where we could beat anybody and that we could win a World Cup. I know people think about that, "You don't know what you're doing and you're being unrealistic." I think anything was possible. My dad would always tell me, don't believe what you read in the papers, but a lot of the papers were writing like "Here we come. The US are coming."

Roger Bennett: It wasn't just the US players who were believing in themselves. What they'd achieved on the field in South America was turning them into global idols. A day after the game, schoolchildren kicked the ball on the Paysandu playground. They were recreating the victory against Argentina. An 11-year-old kid says, I"'m not going to play unless I get to be Eric Wynalda because he always gets the goals."

Eric Wynalda: Where'd you hear that?

Roger Bennett: In the New York Times, they wrote it.

Eric Wynalda: Oh my God. That's the greatest compliment of all. I think the people that saw us play, that actually witnessed that team and that energy and that unity, you couldn't help it. You couldn't help it but walk away from that and say, "Okay, look out."

Roger Bennett: I'm Roger Bennett.

[music]

Announcer: American Fiasco is a production of WNYC Studios. Our team includes Joel Meyer, Emily Botein, Paula Szuchman, Derek John, Starlee Kine, Kegan Zema, Ernie Introdert. Eliza Lambert, Jamison York, Daniel Guillemette, Matt Boynton, Jonathan Williamson, Brad Feldman, Bea Aldrich, Jeremy bloom, Isaac Jones and Sarah Sandbach. Joe Plourde is our technical director and his round composed our original music. Our theme music is by Big Red Machine, the collaboration between Aaron Dessner of The National and Justin Vernon of Bon Iver. Special thanks to Adam Ty Schultz, Marcus [unintelligible 00:27:40], and Tomas Naza. This episode included audio from CONMEBOL, Radio Mitre, and BBC. For more about this story, including a timeline and more go to fiascopodcast.com.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.