Why Do Only Men Have Pockets?

( The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Costume Institute. Art Resource. )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. I want to check in and see how everyone's doing with the September Get Lit with All Of It Book Club pick. We are reading the novel The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by National Book Award winner James McBride. It tells the depression era tale of a small Pennsylvania town where Blacks and Jewish immigrants coexisted along with the clam, by the way, and they have interlocking destinies. The New York Times calls it "a murder mystery locked inside a great american novel, charming, smart, heart-blistering and heart-healing."

It is so good that I read it already, and I am now listening to the audiobook just to get all ready for next week's event, because I'll be in conversation with James McBride next Wednesday, September 27th at 6:00 PM along with special musical guest Carla Cook. Now in-person tickets are sold out for the library event, but you can follow along from the comfort of your home with a free live stream. Head to wnyc.org/getlit for more information. That is in the future, now, let's get this hour started.

[music]

Spend any time on the internet, and you may have seen the meme of a woman being complimented on her clothing, and she enthusiastically declares it has pockets.

[musical meme]

Hey, I like your dress. Thanks. It has pockets. Pocket. Pockets. Oh, my god, the dress has pockets. Can you believe her dress has pockets?

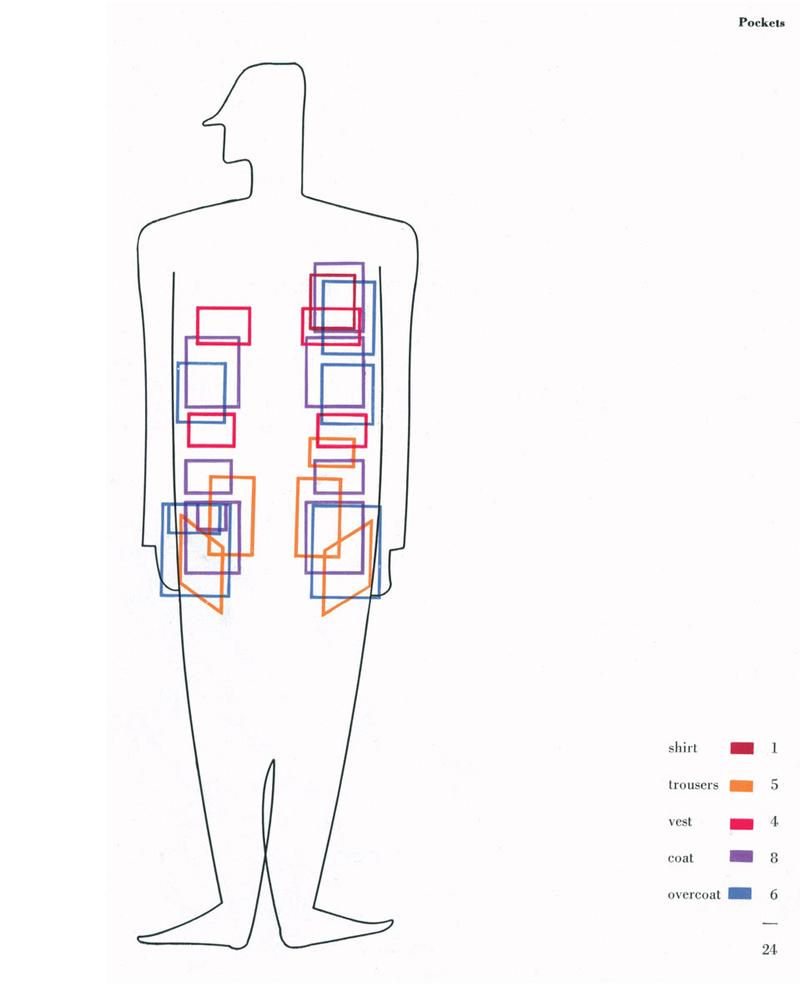

Alison Stewart: For hundreds of years, humans have found solace in the fact that the items they cherish the most are right where they need them to be; inside their pockets. A new book investigates the origins of the pocket, how its existence intersects with gender, class, and power. It's titled Pockets: An Intimate History on How We Keep Things Close. It's a meticulous cultural study that revisits a time when both men and women wore purses, shows how pockets became a rite of passage in Western culture for boys, how hands in pockets sometimes indicated lustiness, and discusses the significance we assign to the contents of an individual's pockets. Joining us is the author, researcher, Hannah Carlson, who is an authority on clothing history and senior lecturer in the apparel design department at the Rhode Island School of Design. Hannah, welcome to All Of It.

Hannah: Oh, thanks so much for having me. I loved your musical memes.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Listeners, we'd love to hear from you. What do you keep in your pockets? How often do you find cash that you have long forgotten? Tell us the strangest thing you found in your pocket that you don't remember how it got there. Maybe you prefer a dress with pockets or without. Tell us about your pocket preference. Give us a call. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call in and join us on the air, or you can text to us at that number if that's more convenient. You can also reach out via Twitter or DM us on Instagram, same handle for both @AllOfItWNYC. We are talking pockets. Where does the word pocket come from?

Hannah: Well, it's a combination of poke, which was Anglo-Norman for the French word poche, which means bag and the diminutive et, so like a cigarette. This is a pocket, a small bag.

Alison Stewart: I think a lot of people take them for granted that clothing has had pockets forever and ever. Before pockets, how did people hold on to their personal belongings?

Hannah: Everybody just carries a bag, and that bag could be carried all sorts of ways. You could strap it over your shoulder, over your forehead, hold it in your hand. Often you just connect it to a belt, and it's found in the Paleolithic period, oh, no, I'm sorry, not that far back, but the iceman from 3000 BC had a bag attached to his belt, and it's just a common way to carry things.

Alison Stewart: What's the first documentation of a pocket?

Hannah: The first I found was in a tailor's bills. Around the 1540s, for example, Henry VIII, his tailor says, "Okay, here's the bill for your clothes, and this is the bill for adding this leather pocket here in those clothes." You see no explanations of why tailors were going to include pockets, but they just suddenly start showing up.

Alison Stewart: When they first show up, what do people make of them?

Hannah: I thought that they would think, "Oh, what a nifty contrivance. Instead of carrying your bag at your belt, have fun to just stick it into your big puffy breaches." That's what men were wearing in the 1550s. They looked like pumpkins or big bloomers. Surprisingly, they were considered really worrisome spaces. People were anxious because you could also carry the first small-scale handguns. The new invention, the wheel lock pistol allowed people to fire at will. Guns had before been really cumbersome, heavy, it would take two hands to light the flare to ignite the gunpowder. Now you could secret a gun in your pocket and conceal that you had bad intentions. Queen Elizabeth I and James I issue these proclamations, and they try to make sure that men would stop hiding their pocket pistols in these new secret places that were all about his body.

Alison Stewart: Did women have pockets at this time?

Hannah: There are a few. Queen Elizabeth had a few pockets in her more casual gowns, but women really continue the medieval practice of carrying a bag that was dangled from her belt. Women continued to do that until around 1800. It's just you reach into a slit at your skirt and there were your what historians now call tie on pockets, and they were big. They were shaped like tears or pears, and you could stuff a lot in them, and they were very useful.

Alison Stewart: We've got a text that says, "Pockets! My teenage son is into fashion and thrifting, which has led him to buy a pair of two women's pants that get mixed in with men's clothes sometimes. He soon discovered that women's pants have much smaller pockets. I'm hoping he will make his mark in the fashion industry by making pockets equal." We're a little ahead of it, but you get to that in the book that women's pockets are actually much smaller in clothing. Why is that in modern clothing? We'll just jump ahead.

Hannah: Yes, for sure. Why, is the big question. I think it's about our ideas about what women need and is their clothing supposed to be functional or beautiful? That divide between utility and beauty is one that we still carry with us. It's also just the way that dress developed. Men's wear and women's wear developed very differently. Men's wear developed the uniform of a suit early on, and in that suit, pockets were expected. They become, the suit is a uniform, and the uniform was industrialized early. By 1850, you could go to Brooks Brothers and buy a suit off the rack. Women's wear does not develop that way. It's when you get to modern women's clothes, women by that point have been carrying a bag.

Let me back up. I'm sorry. We jumped ahead, so I didn't spool out the story, but around 1800, those bags that women wore under their skirts no longer fit. People joke that women then had to carry their pockets in their hands, and you have the first fashion handbags. As long as men have had suits and all these pockets and the fact that they're just automatically there, women have been carrying either their bags under their skirts or the purse. The simpler answer is that there's just this expectation that men's wear will have pockets and women's pockets have come and gone [laughs], and you just don't know if you can expect them.

It's because in a way, women didn't have a uniform. That dress you cannot buy off the rack until 1920. There is no standard form, no standard place for pockets. There's this laziness so that manufacturers think, "Well, women have handbags. Why on earth would I take all the trouble to include a well-working pocket?" It's an engineering puzzle to get a pocket to fit well, and so if you ever want to cut costs, you say goodbye to the pocket.

Alison Stewart: Speaking of, we have a designer calling in on line 1. It's Naomi from Brooklyn. Naomi, you are very interested in women's clothing with pockets. All of your skirts have very big pockets, right?

Naomi: Yes, absolutely. We think of pockets as not only a central part of our design, but also our design process. We have pockets in almost all of our garments, especially our signature Oxford. I think that putting pockets in a garment especially for a woman, acknowledges that the garment and in effect the wearer is something not just to be passively looked at, but to be actively used and listened to. Essentially, designing with pockets acknowledges that the woman wearing it has a life beyond just being looked at.

Alison Stewart: Is this something from your personal life? Is this something that you learned in design school? This just something you've observed, and your clients have asked you for?

Naomi: It's something I definitely observed, and my clients ask for, but it's something that I've just grown up- I've grown up making all of my clothes from childhood, and when you make your own clothes, you can make them however you want. I never made clothes without pockets. That's just always what I wanted. That translated very easily into what my customers wanted as well.

Alison Stewart: You can shout out.

Naomi: Yes. I am Naomi of NAOMI NOMI, and we're a made to order garment line based here in Brooklyn, and we make women's work wear and specialize in shirting. Again, all of our clothes have pockets.

Alison Stewart: I love that. Naomi, thank you for calling in. Hannah, I wanted to ask you about. There's another company, and I think you mentioned it in your book Argent, and that is their entire sales pitch. It's women's blazers with inside pockets. I think the tagline says something like "your phone, your pencils and your tampon can come with you". I found that to be such an interesting marketing angle.

Hannah: It's becoming frequently a great marketing angle. All sorts of brands are highlighting that. I think it suggests a couple of things. This recognition that women do want to act and do. As Naomi just suggested, they want to be in the world with ease. You don't want to be stuck having lost your handbag somewhere, but it's up to the buyer, the purchaser, to seek out those folks who highlight that they've included pockets. It's still up for women to make sure that their clothes are outfitted this way. It's not yet standardized. That's why these sorts of promotions, I think, work.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Jarrell from the Upper West Side, who has a comment/question. Hi, Jarrell. Thanks for calling in.

Jarrell: Hi. Thank you. I'm thrilled that the book has been written about pockets. It's just so exciting, because I've been thinking about pockets for a long time, but I had mainly one realization that seems to be the answer. Now, I have to read your book and find out other things. There was no reason for us women to have pockets, because we didn't have to carry money. Much later when clothes were first developed that was the case in my opinion that then designers don't like to spoil the line of the clothes.

Alison Stewart: Interesting. Let me get Hannah in here in terms about the line of clothing.

Hannah: Well, that's a common, common excuse in my mind. I have a wonderful moment where Elizabeth Katie Stanton, the women's suffragist, women's rights advocate at the turn of the 20th century, writes all these articles about pockets and wanting them. She was incensed that women's wear did not have useful working pockets. Around 1898 she includes this discussion, this back and forth she has with her dressmaker. She says, "I want pockets." The dress maker says, "Ah, I'm not going to include pockets. They'll bulge you out just all over," and they have this fight.

In the end Stanton gets this dress and they do not include working pockets, and she's infuriated. The notion that women's aesthetics of the line and the smooth look I think though is an excuse, because there are all sorts of places to hide wonderful pockets. All sorts of American, say, sportswear designers in the '40s and '50s figured out that you could include fun big bulging pockets at the hip, and they only made your waist look smaller. I think it's an excuse to consider the silhouette above function.

Alison Stewart: Well, throughout the book you examine how pockets become a symbol of power and who gets a pocket matters. In one instance you wrote, "Pockets were not guaranteed nor pockets guaranteed in clothes enslaved people endured." What was the rationale behind slave owners excluding pockets on their enslaved clothes? How did this work as a preemptive strategy?

Hannah: Well, I think clothes in the 18th century are all made by hand, and so there's quite a lot of variation in how they looked, and that particular quote occurs because a formerly enslaved man remembers his childhood in the 1930s. He's recalling what it was like, and he remembers that as a kid he didn't have pockets in his trousers, and the reason was so he couldn't steal eggs. There was this preemptive defense against theft. I think it's clear that it would cost money to add pockets, but also having a jacket with pocket flaps and also the wonderful extra useful space denying that is another way to mark out the free from the enslaved.

Alison Stewart: We have a text that says, this is Emily, "My mother deliberately left money in coat pockets and pocketbooks different amounts each time, and was surprised with each new 'discovery.'" Listeners, we want to hear from you. What do you keep inside your pockets? How often do you find something in your pocket you've long forgotten about? Tell us about the strangest thing you found inside your pocket that you won't remember how it got there. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Are you someone who prefers a dress with or without pockets?

Gentlemen, how do you feel about pockets 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can join us online or you can text us at that number or send us a message via Instagram @AllOfItWNYC. Our guest this hour is Hannah Carlson. The name of her book is Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close. We'll have more pocket history and more of your calls after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

This is all of it from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Hannah Carlson. She's the author of Pockets: An Intimate History of How we Keep things Close. In the first chapter, Hannah, you write, "Mark Twain counted pockets among the most useful of inventions. For a man who had witnessed the rise of the steamship, the telegraph, and the cross-continental railroad, pockets would seem a surprising choice." Why would a pocket be considered revolutionary by Twain?

Hannah: Well, I just love this book. It was considered one of the first-time travel novels, and he's writing at the end of the 19th century. It's a time when there's all this romanticization of the medieval era. It's just when industrialization is really hitting its stride, and people are looking back, and he has this nightmare. He's stuck in medieval armor and he says, "Everyone's romanticizing this moment." We have Tiffany lamps, all this stuff that looks medieval, all this architecture. He says, "It was terrible. Look at these guys in these iron dudes." What kind of designer would make armor without pockets?

He has a nightmare about being stuck in armor. Then he writes a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. I love this notion that it's because of Twain's dream of the lack of pockets that he begins to think about, "Well, why are they so useful?" That actually helped me think about that too. They just allow us to move through space, to be prepared, to keep our memories. They are these fellows that come with us that are small. We never think about them, but they're actually quite important.

Alison Stewart: What are some of the other literary references to pockets that you came across in your research, and what are these references? What's an example of a reference that really reveals something about culture?

Hannah: Dependent on literature for this book. I think literature helped me think about how it is we interact with clothing. Another similar story I guess in a way is the Robinson Crusoe story. Have you ever had that feeling where you locked yourself out of a car or locked yourself out of your home, and you make that patting yourself down gesture and you think, "Oh, do I have anything useful?" Robinson Crusoe does that when he's cast away on this island. He is stuck without anything useful. He thinks, "Oh, I'm doomed. I'm going to die."

Later the next day, he looks off to the shore and sees his boat has foundered. There's this wonderful moment that people made fun of for years after the 1719 publication of the book in which he strips his clothes, he swims to the boat, he loads up with all this useful stuff. He's hungry, so he loads up, he gets rations, he stuffs it in his pockets and he swims back ashore. The joke was that Robinson Crusoe had swum to shore naked with his pockets full of biscuits. I just think that's such a lovely sort of encapsulation. Even men could strip at the shore, take off all your clothes, and still expect to have your pockets at your disposal. Women don't have that expectation, but pockets are so naturalized that we think they'll always be with us.

Alison Stewart: Someone that goes by Dangerous Coats on Twitter, has texted us a poem that says, "Someone clever once said, women were not allowed pockets in case they carried leaflets to spread sedition, which means unrest to you and me, a grandiose word for common sense, fairness, kindness, equality. Ladies, start sewing dangerous coats made of pockets and sedition."

Hannah: Exactly, what could you carry in your pockets? There was a tailor quoted in the New York Times around 1890s who said, "Those bicyclists with their bloomers are making me insert pockets and pockets made out of leather. Do you think they're carrying suffragist speeches? Could they be carrying revolvers?" What can you do when you are well-equipped was one concern.

Alison Stewart: I've got a couple of questions for you. Andy has texted in, what is the origin of deep pockets?

Hannah: Of deep pockets? I'm not sure what-- Well, pockets originally were incredibly deep. They might be 18, 20 inches deep. I think they've been with us all along and really the size changes as our clothes change. Pockets originally look like bags that hung from the waist bag and eventually with the suit they become more envelope-shaped, the way that they are today.

Alison Stewart: I think you might mean the phrase, if you're rich, you have deep pockets.

Hannah: Oh, oh, oh, oh, I'm so sorry. Yes, I can't tell you the origins of that but I think money might be the least interesting thing that people carry, because when we think about it, when you've been asking for pocket stories and listeners' pocket stories, those objects are often not money, but funny, strange things. A memento, something that you hold on to just to remember someone, or someone's signature on the back of a box of matches, or an old receipt crinkled up. We carry stuff that, or we're interested in the things that we carry that suggest something about our life, something about what we're doing. It's very rarely that we think that the money that we carry is all that interesting. Except I should say for tales of I came to this country with $2 in my pocket. Those are stories certainly are frequent.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Dan from Passaic, New Jersey. Hi Dan, thanks for calling All Of It.

Dan: Hey, yes, no, I'm just curious about the back pocket for men, where we keep our wallets, which we throw out onto car seat next to us when we get in because we can't sit on it but I remember back in the-- she talked about '18, '19, men used to carry billfolds, well, rich men to specific, but used to carry it in their jacket pockets, their money in their front jackets. We see that thing where the guy opened up and he pulled out all his dollars nice and flat where we now fold them up and stick them in our back pocket. Where does the back pocket that men have to sit on uncomfortably come in?

Alison: Back pocket?

Hannah: I hear a design complaint. I think you should know. Pockets on the seat are actually pretty late. They come about only in the late 19th century. They were considered, actually, I found some evidence that folks wanted to ban them because the worry wasn't that you would carry money back there, but that you might carry pistols, and those backseat pockets were called pistol pockets in the late 19th century. In the US someone tried to ban them, but I think you should take that up with your tailor.

Alison Stewart: You also write in your book Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close about men placing their hands in their pockets and all the various signals this one might give. We've talked about how it might mean someone was armed and that was a concern, but there's also a concern that it was a sexual act. Correct?

Hannah: Absolutely. Yes. Trouser pockets locate to lust. The poet Harold Nemerov says they are dark places in and around erogenous zones. All sorts of people were very anxious about the placement of pockets, and that putting the hand there was actually really rude. Of course, we don't say it too much now, but take your hands out of your pockets was certainly something that etiquette guides and mothers, and educators said. In the late 19th century, certain boys' schools would sew up boys' pockets so that they couldn't hold their hands there.

Of course, it's also really cool. It's the gesture that we see in fashion magazines. James Dean, anyone who holds his hands in his pockets is also aloof. I think that it's sort of metaphoric, this notion that you conceal your hand and you're also suggesting your emotional inaccessibility, a blasé attitude. It oscillates between sexual and psychological, holding the hand in your pocket.

Alison Stewart: Let's take some calls. Judy from Fleischmann's New York is calling in. Hi Judy. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Judy: Hey, thank you. I really enjoy your show, particularly during the height of the pandemic. This topic of discussion, I had a night before last on an international Zoom that I do. We all check in at night. The whole thing was a discussion of how women can't find pockets. We started with the discussion about kangaroos and how they really knew what they were doing and how-- It's just literally, I'm a teacher and when I shop, and I shop like an L.L. Bean, I look and they just never have a significant enough pocket to carry things for your work. You're supposed to what, be carrying a handbag in the classroom. I don't know. It's never anything set up for a working person, particularly a teacher.

Hannah: I agree.

Alison Stewart: Judy, thanks for calling in. Also want to let people know if they go to our Instagram @AllOfItWNYC, you can see some of the illustrations from Hannah Carlson's book Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close. Let's talk to Elizabeth from Brooklyn. Hi, Elizabeth. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Elizabeth: Hi. My comment is very similar to the previous caller. In the '70s, my sister worked as a consultant to six machines, computers, and very few women were in the field at all. One of the things I had to do, every client they went to, they had to log in on a card which men held in their top pocket, many minutes they spent and my sister was going crazy, she couldn't find any clothes where she could keep that card so she was very inefficient and it was just a disaster because she couldn't get women's clothes with the pocket in the blouse and the shirt.

Alison Stewart: We have a reoccurring theme here. Let's talk to Dorothy from Scarsdale. Hi, Dorothy. Thank you for calling in.

Dorothy: Hi. I wanted to talk about the pockets in my mother's jackets. I inherited a fair number of really nice quilted jackets from her and was delighted to find her old handkerchiefs or tissues in her pockets. It was a way of remembering her when she was alive. It reminded me, one person said she loved when she found a ball or a balloon that her mother had blown up because in it was the breath of her mother.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's lovely. Thank you so much for calling in. Let's talk to Cassie from Mendham. Hi, Cassie. Thank you for calling All Of It.

Cassie: Hi. I wanted to share a story about my Mimi's pocket. My Mimi is my grandma, and she's an artist. I remember we got to spend special time with her when I was a little girl, and we were walking into a shop. She was always collecting things for her still life paintings, and there was a bird, a dead bird on the sidewalk. I think it had flown into the window, but it was still in good shape. She picked it up and just put it in her pocket. Then I think she forgot about it. Later that day, we were at the grocery store and she was looking for change to pay for her order. She just emptied her pockets out on the cash register counter and that bird was there. I remember the look of the cash register. I was a little embarrassed as a little girl, but now I look back and it's a really fond memory because having these interesting objects for still life paintings was more important than what other people might think of you and so I really love that memory. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: Cassie.

Hannah: It's just such a beautiful story. That's great.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for calling in. Hannah, you write pockets evolved and continue to evolve as clothing and objects do. How so?

Hannah: Well, they multiplied. They started as one and then became two, and then now I think you look everywhere from the interior breast pocket to the seams in lycra legging. We've fit pockets everywhere. I think as objects evolve, we have to think of different ways to hold them and fit them. There was a huge outcry when the iPhone got really bigger and at that point, really it's not just that we don't have good pockets, but forget putting a really huge iPhone in women's wear these days.

I think the question too is will we still need pockets in the future, when we've collected all our tools in a single object, which is now the phone. I think there's hope for pockets, and I think that redundancy, the notion that they're there for memory as well, as many of the listeners have noted, the idea that we may need a place for a lucky charm, that things in our pockets can sustain momentum will mean that we do keep them even as they change shape and form.

Alison Stewart: We just scratched the surface there. So much good history in this book Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close. My guest has been Hannah Carlson. Hannah, thank you for joining us.

Hannah: Thanks so much.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.