[music]

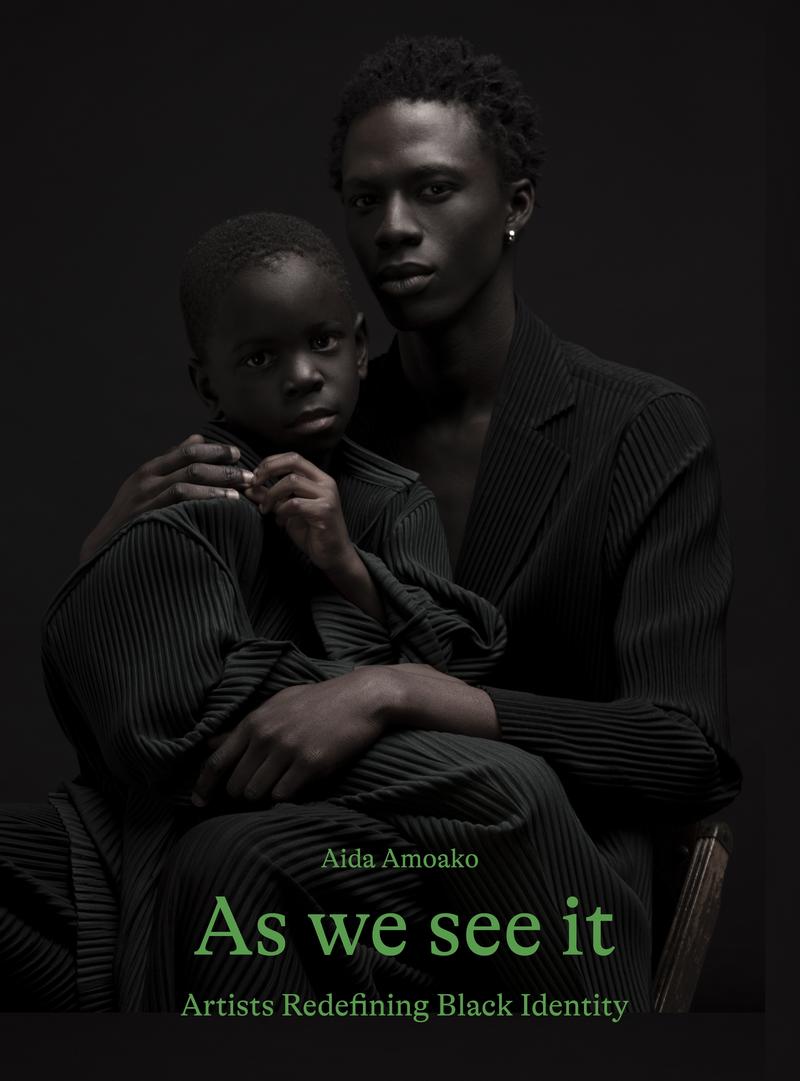

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. As we continue our Black Art History Month series, it's helpful to think about why learning about and celebrating Black art is so important. We just heard about Black art in the past, now, we'll look to the future. In her new book, As We See It: Artists Redefining Black Identity, writer and cultural critic, Aida Amoako, highlights the work of 30 Black artists around the world whose work has contributed to expanding the notions of what it means to be Black.

As Aida writes in her introduction, "The book is not just about looking at Black people, it's also about seeing the world through their varying perspectives. The goal is to afford Black people the fullness of their humanity." Aida Amoako is a journalist, writer, and cultural critic. As We See It: Artists Redefining Black Identity is available now. Aida, welcome to the show.

Aida Amoako: Hi. Hello. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: You decided to approach this book from a global perspective rather than focusing just on American artists or British artists. Why did you feel it was important to zoom all the way out and take a global perspective?

Aida Amoako: I thought it would be good to break out of the Anglo-American perspective, which dominates art books, not because I have a problem with British or American artists, but I just thought if we are going to talk about expanding the notions of what it means to be Black, naturally, we'd go out and look at the Black diaspora around the world. There are artists from every corner of the globe featured in the book, the Bahamas, Nigeria, South Africa. The whole project is about broadening perspectives and looking at the multiplicities of Blackness, so it made sense to broaden it out.

Alison Stewart: You write a bit about the Black gaze in the introduction of the book. What is the Black gaze and where is it in relationship to the white gaze that we talk a lot about?

Aida Amoako: I would explain the Black gaze as perspectives that reject the, what is the word, centralization, the focus of the opposite, I guess, which is the white gaze, the traditional Western gaze that says, "This is what Blackness is in relation to us," and gives the microphone and all the other tools over to people who have a Black subjectivity to tell their story themselves. That's linking to the name of the book, As We See It, to see through our eyes rather than a projection, it's a conversation.

Alison Stewart: What were you looking for in terms of who to spotlight in the book? Did you have certain criteria? Did you have certain goals, a touchstone that you came back to that you would use to help you figure out who should be in this book?

Aida Amoako: I think youth was definitely one of them. I wasn't trying to be ageist, but I was just trying to think of, if we're talking about the idea of a cannon and how younger people, millennials especially, might engage with that, wanting to expand upon things that they've picked up from their own artistic heroes or rejecting and challenging those ideas,

so I want to look at that, but also gave me the opportunity to look at how social media has helped these artists gain a platform and share their ideas, so youth was definitely one.

Apart from that, it was open really as in the same way that picking artists from not just American Britain, yes, it was open.

Alison Stewart: You write in the introduction, "The unassuming prefix re became a source of unexpected insight while researching this book." What is it about that prefix that is so important to the work of the artists in this book?

Aida Amoako: I think because the connotation of re is to do over, but when you look at it, it's not just doing it again, it's with the eye to improvement. As I was doing research for these artists, it just kept on coming up, reset, reimagine, reevaluate. It was a linking thread between a lot of the artists, this idea of looking at what's been done, what's already there, and thinking, "Well, how can I expand this? What has been left out of this conversation?" That's how re came into play.

Alison Stewart: It's fine. My guest is Aida Amoako, the name of the book is, As We See It: Artists Redefining Black Identity. You mentioned social media earlier, let's look at the both sides of it. How has the emergence of social media and smartphones opened the door for Black artists, and what are the potential pitfalls of social media for Black artists who share their work that way?

Aida Amoako: I think quite a few of the artists have used it as both a platform and a tool. It's allowed them to cast for models in a different way, in a non-traditional way. It's also allowed them to do more lateral networking rather than trying to get past all the old gatekeepers. It's also allowed them to find an audience that they can have an intimate relationship with before they ever get to show in the gallery.

A lot of the artists [unintelligible 00:05:53] in the book became prominent at a much younger age than the generation before them. There were quite a few who became known when they were still teenagers, in their early 20s. I think that's how it's encouraged artists. I guess the negatives would be, I guess, the idea from maybe some of those gatekeepers of a frivolousness, that their art isn't as legitimate as artists who came through a more traditional route.

For example, there are artists who create solely using an iPhone and then digitally edit their work. They've had to come up across the accusation of, "Well, is this really photography?" I think it's a gatekeeper battling, but overall, the artists seem to appreciate having had social media to boost their platform in a way that they wouldn't have had if they'd, for example, gone to art school, and then gone through that way.

Alison Stewart: You include some groundbreaking fashion photographers in the book. Who was important to include in the world of fashion photography?

Aida Amoako: I think Nadine Ijewere. She was the first woman of color to shoot the cover for British Vogue in its over 100-year history. She did that under the tenure of Edward Enninful, who is a Ghanaian-origin Black British editor of British Vogue. That was in 2019, so just to show you how long it took for a woman of color to shoot the cover. She was also the first Black woman to shoot the cover for US Vogue in 2021.

Again, centuries going past before these landmarks happen. I think Nadine is really important because she talks about the ideas of representation and inclusion, and not wanting Black people in art their presence, to be considered as a box-ticking exercise or being considered something spicy to add on. She says, "For Black people to be present, why must something have to be disturbed?"

She's very interested in moving past the first this, the first that, and it being natural that there would be Black people reached in fashion photography, both in front of and behind the lens.

Alison Stewart: You also include a photographer who is the first Black cover photographer of Vanity Fair.

Aida Amoako: Yes, Dario Calmese, sorry. He shot Viola Davis in this just stunning, stunning photograph, where she has her back exposed and she's in part profile. He called it a love letter to Black woman. There was also a bit of controversy because the visual reference was-- this photograph called Whipped Peter, which shows an enslaved gentleman with a keloid scarred back. There was a discussion of, "Is this the glamorization of suffering?" For him, it was a love letter.

He also has a series called Amongst Friends, where for over five years, he shot his friend Lana Turner, who was shot in the most incredible outfits, which are evoking the old-new look-esque. It was just a blaze on focusing the shoes, on the cut of her skirt, on the top of the hat. A love letter to Black women, I'd say comes up quite a bit in his work.

Alison Stewart: Since we're New York Public Radio, I wanted to ask a bit about a few New York-based artists in the book, Lina Iris Viktor combines photography and painting to create afrofuturist portraits. How does her work combine fantasy and history?

Aida Amoako: Well, she takes a look at mythology. She creates these self-portraits where she mythologizes herself, creates-- Oh, sorry about that. Makes herself into a goddess. By referring to those mythological narratives and bringing the afrofuturistic angle, she blurs these lines, these temporal lines, justice philosophy about rejecting rigidity and that there should be solid center. She merges afrofuturism, but ancient, ancient mythological stories about goddesses as well.

Alison Stewart: Another New York-based artist is Donovon Smallwood. He's a photographer. What do you admire about his work?

Aida Amoako: He's self-taught. He recently released his first monograph and he took photos through Central Park in the middle of the pandemic around the time when New York was the epicenter for COVID in America. I remember those 'Is New York dead?' article. 'Is New York done?' His response seems to be to say, "Look at this. Here's a place of solace and escape and aloneness, but not loneliness." There was no sense of mourning despite everything that was going on. He gives his subjects, his Black subjects, an escape from the pressure cooker of the city by transforming Central Park into this other worldly escape. The relationship between open green spaces and Black people is a thread throughout his work as well.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is As We See It: Artist Redefining Black Identity. I was speaking with this author, Aida Amoako. Aida, thank you so much for sharing your research and your work with us.

Aida Amoako: Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: That is All Of It for today. On tomorrow's show, horror writer Stephen Graham Jones. He tackles indigenous identity through his terrifying but really good novels. He'll join us to talk about My Heart is A Chainsaw and Don't Fear the Reaper. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening and I appreciate you. I will meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.