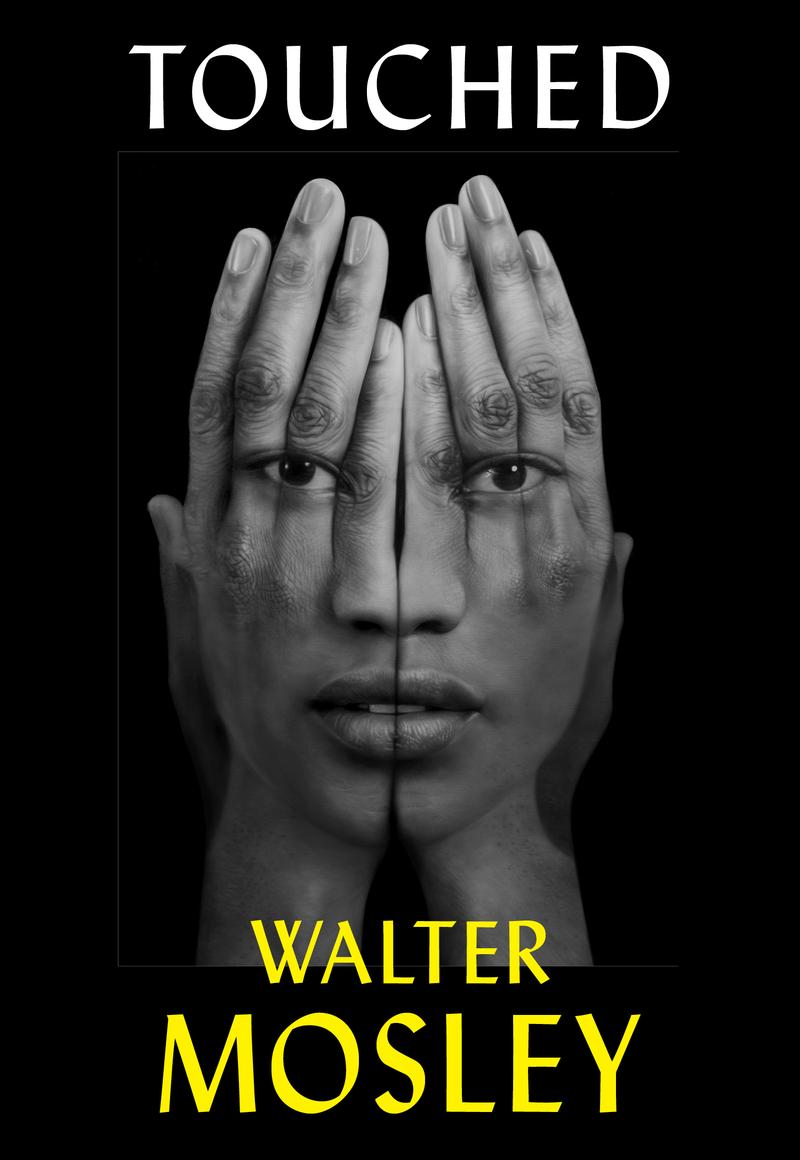

Walter Mosley's New Sci-Fi Novel, 'Touched.'

( Courtesy of Grove Atlantic )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on-demand, I'm grateful you're here. On today's show, we'll talk with actor Vicky Krieps, whose work is the subject of a retrospective this weekend at the Metrograph. We'll also talk about this weekend's Coney Island Maker Fair with three of the participants, and we'll discuss the varied cuisines of Latin America with cookbook author Sandra Gutierrez. That is our plan, so let's get this started with bestselling author Walter Mosley.

[music]

Alison Stewart: The Los Angeles Times said Walter Mosley's new Sci-Fi thriller Touched is "Like nothing else you've ever read, and it's so, so good." The briskly paced, action-packed story introduces us to an average 47-year-old Black family man, Marty, who lives in LA and has worked at the same company for 17 years. Marty wakes up one day to learn that he has been chosen to help save the world and has to protect humanity from an evil being named Tor, who is bent on genocide. Telling Marty during their first meeting, "Life is stupid. Only eternity is precious."

In this story, there are cops, Aryans, fierce kids, and Mosley's deft commentary on justice. Touched will be released on October 10th. Walter Mosley will be appearing at P&T Knitwear Bookstore and Event Space on Sunday, October 8th at 2:00 PM, and we are thrilled to have the award-winning legendary author of more than 60 books in studio today. It is a pleasure to meet you.

Walter Mosley: You too. It's great.

Alison Stewart: In reading around about the book, you've noted that Sci-Fi writing is liberating because you can break rules. Was there a rule that you were really ready and willing to break?

Walter Mosley: Well, it's only if it's necessary. Different genres do different things. Crime is great if you have a mystery or you're having some issues with justice, and of course, if you're thinking about your heart, romance is always the thing that might work its way in or out. A lot of times when you're thinking more philosophically, science fiction is really the only thing you can do. Or if you're trying to recreate our mechanical answers to problems. I never want to break anything unless there's no other choice.

Alison Stewart: That you need the new avenue to explore something?

Walter Mosley: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Science fiction is often a vehicle to write and discuss about very real-life issues, whether it's gentrification or colonization, assimilation. What were some of the themes or issues you wanted to bring up in this book, specifically using Sci-Fi?

Walter Mosley: Well, there are a few things. One, for me, is worrying or thinking about the political issues in this world, in America, where you have this so-called Left and the so-called Right, between so-called Black and so-called white people, arguing with each other and thinking, "But if we only work together, then we could answer the problems." The only answer is for us to work together and to agree these are our problems. Whether or not we like each other, we have to settle it. One thing is I wanted to address that.

Another thing is I wanted to just make a very light touch thinking about the speed of light. When you have the speed of light and you look out there and you say, "Well, 100 million light years. You mean I have to travel for 100 million years at the speed of light to get to that thing? I'm never going to get there. Even if we had a ship, we would go through thousands of generations just to get there, maybe tens of thousands." If indeed there is like a big bang and there's a primal atom that's at a moment where everything is right next to each other like millimeters rather than hundreds of millions of light years.

I just wanted to talk really, a tiny little bit about that, and also, and the third thing, maybe the most important whenever I'm thinking about science fiction is one problem that I see in science fiction is that it usually makes humans the most important thing. It's like a time when they said well, the sun goes around the Earth. It's a mistake. We need to see ourselves in relation to the rest of at least life on Earth as more closely intertwined than we're used to thinking.

Alison Stewart: Yes, in the book, there is a distinction between life and humanity.

Walter Mosley: There is? What did I say?

Alison Stewart: I picked up a distinction between life and humanity.

Walter Mosley: Well, humans think-- No, there isn't a distinction, and that's the problem. We think there's a distinction between life and humanity, that there's humans and then there's everything else.

Alison Stewart: Oh, I see what you mean.

Walter Mosley: We think that trees don't have feelings. We think that we're the smartest creature, which may not be true. The way that we see ourselves, we get blinded to the reality of our lives. One of the great things you can do with science fiction is open that up and say, "Well, we're really not that important. We're really kind of inconsequential."

Alison Stewart: We're actually agreeing. [laughs]

Walter Mosley: Okay, but that's not a surprise, right?

Alison Stewart: No.

Walter Mosley: You hear something and you hear something else.

Alison Stewart: It would be terrific if you could read the first three pages of the book for like--

Walter Mosley: Well, I will. I have to change one word, I think, for the radio, but that's all.

"I awoke on a Saturday morning with the plan fully formed but fading in my mind. Nothing else had changed. It was as if I had gone to sleep years before contemplating a tricky conundrum and remained in that doze until the naughty question had been completely disentangled, at least mentally so, at least for a while, but when I awoke, it was merely the next morning, as if time had folded back on itself, depositing me where I was before.

Tessa was in bed next to me, sound asleep. Her hair was wrapped in violet nylon netting. She'd sleep for two hours more. Brown would certainly be asleep in his room, and Celestine, whom everyone called Ceal, was probably sitting in her bed, reading a library book. I sat up and took a deep breath that felt like my first inhalation in a very long time. Cells began to fire in my body. That's the only way I can describe it. It was as if my physiology had also undergone some kind of transformation.

I could feel my organs and glands pumping out chemicals, altering tissue and even bone. There had been an azure plane where beings not human had poked and butted me fondled and sexed me in ways that made no sense in the earthly realm. I was there, and others were, too. Other people, human beings, being prepared for something, for some things. It occurred to me that we were not all in accordance. Our plans were different, and sometimes even at odds.

There were 107 assigned to the great change, but our tasks often seemed to contradict one another. 107 human beings conditioned and trained to prepare for the transition, but there were other creatures, too, other earthly life forms that were there to complete us. Or maybe we were there to complete them, or even more accurately, to complete a circuit, a turning, a revolution.

It was only on that Saturday morning, with Tessa sleeping next to me and the sun slanting in through the seam of our heavy curtains, that I understood the plan in its totality, and even then, while I was rousing from my centuries-long sleep, the lessons I had learned were receding into the shelves and cubby holes of my unconscious mind. I can remember only some of it now. After the first skirmish in an intergalactic invasion, there was a place that gave the impression of many shades of blue, but I can't say that my eyes were working there.

I was aware of different beings from a vast range of planes and realities. They spoke to me, but in ways that transformed rather than informed me. They were like a congress that met only once, decided on the fates of worlds, and then disbanded when their words, their annunciations, had been received and digested. My world, they said, was wrong. It, the planet itself, had spawned a disease of which I was a part. This contagion had begun to multiply and it had to be rendered impotent by any means necessary."

Alison Stewart: That's Walter Mosley, reading from his new book, Touched. We heard in there, the next line talks about being the cure and being an antibody. Was this written pre-pandemic? During pandemic? Post-pandemic?

Walter Mosley: It was before the pandemic. I'd written it quite a while ago. I was trying to remember today how long ago I wrote this, but it was like maybe four years, maybe five, but in this one, we're COVID, rather than--

Alison Stewart: Did it feel different to you after you read it, after COVID, after revisiting something you've written before?

Walter Mosley: No, there were things that scared me about COVID in the beginning, certainly, but what COVID did was it pushed me back into the life I had lived before. I was doing work in California on television and movies and that kind of stuff and I really like being in a place and not having to go out all the time.

Alison Stewart: Martin, who we hear from, Marty, what would a normal day be like for Martin, just before this book starts, before page one of this book?

Walter Mosley: Well, it's interesting. He's a Black man in America, but I think he's not all of that aware of it. He has his wife, he has some children. He really loves all of them. He feels very completed by that relationship and would like to continue it, even though he has this big job, which may be antithetical to humanity. He goes to work every day, comes home every day, spends the weekend, and pays a lot of attention. I think in this beginning where he knows exactly what his children are doing, even though he can't see them. He might be wrong, of course. The son he's still asleep because he sleeps late, and she reads books out of the library because that's what she loves to do and he's so happy knowing that he's not going to stay happy.

Alison Stewart: He's not. What does he think has happened to him when he realizes he has physically changed? There's a sense of, does he think he's unwell? Does he understand what's coming?

Walter Mosley: I think it starts out that he thinks he's crazy. "I'm insane. I think all of these things, they're so clear in my mind, in my heart," but slowly when he starts to realize physically he's different, physically he can do things that other people can't do. I like it because he's Marty and you said Martin. There is a Martin who lives inside of him because he has an ideal self. That ideal self when you're 12 years old, who you want to be. That's part of him because now he doesn't like his ideal self, but his ideal self takes over sometime because he needs somebody more didactic and also physically stronger and aggressive.

Alison Stewart: Before we move on to that part of the story, he's one of 107 individuals, beings, who are supposed to save life and save humanity. How did you arrive at the number 107?

Walter Mosley: I was trying to remember that, Alison. I think it's a prime number. 107 is a prime number. That was one thing. I hope I'm right about that. Well really, there's a literary answer to that question because I wanted to start to write a series of novellas that would deal with this large question that humanity has to answer about how can it better itself and so I thought, well, 107 volumes would probably work. In thumbnail fashion, I've outlined 69 of them, I think. It's never going to happen. I'm certainly too old to write 107 novellas in one stream but it was fun to think about.

Alison Stewart: Our resident math person says it is a prime number.

Walter Mosley: I thought so. I thought it was.

Alison Stewart: Before Martin, Marty, we, the reader can get a handle of what's going on, that he's on the submission and he's going to have a new facet of himself is going to emerge. He's arrested by really aggressive officers on a fakish charge of indecent exposure in front of a minor. He was sleepwalking on his own balcony, and this all happens very quickly. He's arrested, he's swept off to jail, he's in front of a judge. How did you decide on this brisk pacing?

Walter Mosley: Well, it seemed to me that you needed to do it. You imagine living in whatever Poland was called in the 13th century and then you have these Mongolian hoards coming. You live every day. You have a farm, you have your family, you do whatever you do and then one day, there's a 100,000 soldiers just yelling and running across. That's the moment that this is. This moment, decided by other beings completely than humanity that says, "We need to change the world. We need to change it now. You're part of it. This is what's happening. Get to work."

It's why I don't have any chapters in this book. I can't slow down for chapters. It's not like something happens and we wait a little bit and then something more happens and we consider this is like, "It's urgent. It's now."

Alison Stewart: My guest is Walter Mosley, we're discussing his new novel Touched. It will be out on October 10th. He'll be appearing at P&T Knitwear on Sunday, October 8th at 2:00 PM We'll have more with Walter Mosley after a very quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour is Walter Mosley. His new book is called Touched. It is out October 10th, and Walter Mosley will be at P&T Knitwear on Sunday, October 8th at 2:00 PM. Our audience has learned about Marty, where Marty is, what Marty has to do. A version of Marty, whether it's his alter ego or his id, or just who he is when he lets himself be is this person Temple. Temple's actually the one that keeps people safe. Temple has all the extra strength. It's Temple who takes out white supremacists, who were planning to rape Marty in jail. What are some things that Temple can do that Marty couldn't possibly do or that Marty might want to do?

Walter Mosley: Well, even though they're both in the same body, Temple can access the strength that he's been given by these other powers and he can use it. He can also see things, he can see threats, he can see issues, and he can make decisions. This has to be done now rather than sitting back and thinking about it, trying to discuss it that Marty would do. Also, he has much better sex with Marty's wife than Marty does which Marty doesn't like. It's wonderful to be jealous of yourself. It's fun.

In the end, he doesn't have the plan. He doesn't understand what life is. He only understands how to protect and how to fight. They work really well together. I think it would always be a good thing to be able to be two people inside of yourself because life is so complex. One guy can't just take care of it.

Alison Stewart: Temple can kill a man with ease. He's got this sixth sense. He knows when things are going to happen. Tessa, his wife, assures Marty that she loves Marty, even though she has this fiery sex with Temple. Does, she believe that? Does she really love her husband Marty and why does she want him to know this?

Walter Mosley: Well, she doesn't want Marty to feel bad. Marty has really helped her get out of where she was and to become a different person and she likes the person she's become. Also though, because she has been infected with whatever potency has been given by these other beings, she can see him very clearly, and she knows, no, it's the same guy. You think that there's two different guys, but it's the same guy. It's you. Which he doesn't really, I think, understand till the end of the book, but he does finally come to that. She doesn't see the split.

Alison Stewart: Right.

Walter Mosley: She says, "Oh, well, this is this side of you, and this is this side of you. That's all." She knows men. Men on the whole don't know men. They are men, but they don't know it but she understands.

Alison Stewart: It made me think of, and hearing you just say it now, of that Key and Peele sketch with President Obama and his anger translator. Have you seen this?

Walter Mosley: Oh, yes, I have seen that. Yes, yes, yes.

Alison Stewart: Where Obama gives a very political answer and is his anger translator says what we'd really like to say. That made me think, and if I'm wrong, tell me. I know you'll tell me. What is it you wanted to investigate about the right to rage?

Walter Mosley: Well, it's interesting. I'm not sure I'm investigating it, but it's there. Marty and his whole family have a lot to do with these three white supremacist guys.

Alison Stewart: Who show up.

Walter Mosley: Yes. There's all kinds of rage inside of them that he, and also Temple, understand. They understand it in a very clear way. It's just part of who we are, all creatures, sea otters and cats and wasps. There's so much in the world, which is just natural, but we feel like we're not natural, that we're more, cogitative, many of us do. Then a whole bunch of us only think that we can be raging. This is all part of the same thing. You can see it in your dog. How come you can't see it in yourself?

Alison Stewart: Not only does Marty have to deal with the cops harassing him, he has got to deal with the Aryan brotherhood showing up and then walking death in the form of this Tor Waxman who would like to recruit Marty Temple to his side. I found Tor very frightening. What do you think makes him so frightening?

Walter Mosley: Well, I think the absoluteness of death, if you don't deconstruct it, is really frightening to any creature who can imagine a future. I can imagine the future, but I can also imagine the future without me. Most creatures even if they know that somewhere, it doesn't come up except in very extreme situations. The thing is, is that we have to understand how death is actually subservient to life. It's not the other way around. When you see it, you're thinking, "Oh my God, death is going to come get me," and says, "Well, it'll never win." It may come get you and it will come get you, but it'll never win. It cannot win. That's the final understanding.

If you can get to that point, then you may not be afraid of it, but death you're just sitting there thinking you're about to die or if you're going to be executed and, "This Thursday at 11:25, they're going to kill me." It's that, it's that death sentence.

Alison Stewart: It's also, I found, the idea of touch of all this person, this being, Tor, has to do is just touch you and just sap you of your life source, particularly frightening. I just found him to be particularly, just evil. Just evil.

Walter Mosley: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Even though he thinks he's right.

Walter Mosley: Well, he wants to kill everything. Period. There will be no life, when he is finished, there will be no life at all. Because that's the only answer he can see to what the genome is posing as a threat to the universe. Because he's afraid of that.

Alison Stewart: Right. He also, well, I don't want to give too much away.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: I don't want to give too much away. We're talking about Touched with Walter Mosley. There are all these fights and killings and car crashes and people blasting into people's homes yet it's on the backdrop of an average day in a neighborhood in LA with people, like neighbors, around watching. Why did you want to have that mix of the mundane with this extraordinary action?

Walter Mosley: Yes. Well, again, it's like the Mongolians and it's also you think of Germany in the late '30s into the '40s, Germany and the other German countries like Vienna. You walk out your house one day and you see that they're dragging out a Jewish family, and they're going to take them away and they say, "Well, we're just going to send them to a war camp," but you know what they're doing. You also know that you can't do anything about it. That there's a kind of a-- That we are helpless in the short run. I wanted to see it there and I wanted to see Marty a really everyday kind of guy being just thrown completely into that and he has to survive in it. That's so so difficult.

Alison Stewart: It's sort of funny in the way that the cops just keep getting in the way. There's a supernatural showdown for life as we know it, and the cops just keep showing up and wanting to insert their authority.

Walter Mosley: Yes. Just so true because the police do what they do, but there might be issues that are way beyond them. One problem that law enforcement always has, it has no method to reinterpret the rules. There are rules and you follow those rules no matter what. It's like, no, there's something else going on, but what's going on, they can't touch. They try, but they can't.

Alison Stewart: One thing that happens in the book, which I'm not giving too much away, but it's an interesting moment as these white supremacists, they start working with Marty and his family. They get turned around. This is a bigger-picture question. I would love to hear your answer specifically. Do you believe it's possible to rid people who have been infected by racism, who are racist? Can they be turned around?

Walter Mosley: Well, this is America, right? Everybody in America has been somewhat infected by racism. I don't know about the world because I'm not a citizen of the world. I think, yes, and I think it's very logical in many ways. One, I'm very happy about union activity, nowadays. Unions can really make that happen because how you work with people. How you come together to make something happen, either to get the right salary or to make sure that you grab that big 2,000-pound piece of machinery and make sure it gets on top of something else with nobody dying and nothing getting broken.

All of that, that really satisfying feeling of people working together. I think that yes, of course, and it's necessary. There's no way, you're going to make America work without at least having a labor party. You have to have a labor party. Right now we only have the rich so the Republicans and the Democrats, they go to the same trough. That's a problem.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Walter Mosley, the name of the book is Touched. It's out October 10th. It is banned Books Week and you may know this, and our friends at the New York Public Library have called for an online action today, #Freedom to Read Day, encouraging people to go online, say their favorite banned book, or just support authors whose books have been banned. Your books have been banned.

Walter Mosley: Yes. Sometimes my books have been banned and I think it's really important. The thing I get out of that the most is the library. The library is really the bulwarks of our political freedoms. They're always protected. When George Bush kept running around and said, "I want to know what everybody's reading," they said, "No, that's freedom of speech. You can't do that." It was great when the librarians did that. I'm glad that they're still doing it.

I imagine they say, "Oh, hey, listen, you have to come behind the desk. Here's all these banned books." I know Penn's been doing a lot of work lately. I've done some with them. Not a whole lot, but--

Alison Stewart: Well, I want to ask you about one of your banned books, so we can talk about it for just a moment. At least one Texas School district has banned 47.

Walter Mosley: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Will you tell people about 47? Let's talk about 47. [laughs]

Walter Mosley: Well 47 is a story about, a Black slave boy, enslaved boy on a plantation in Georgia in the 1840s, who meets this alien, who is in the form of another young boy and they work together to change the world. They have a complex temporal relationship. At some point, the alien has been around longer than 47, but on the other hand, there are times when 47 has been around, longer than the alien and so they're teaching each other. He's there to tell people what it's like to experience slavery. In the long run, that's what he's going to be doing.

I know that it got banned. I don't know. It's people being afraid of-- People have always been afraid of their victims. Native Americans, there was such fear of them and the fear was, well they scalp people, they rape people, they do this, they do that. I said, "No, wait, wait a second. That's what we're doing to them," and we're doing it a lot more. We know that unconsciously and we're so afraid. That's why I think that's why people are afraid of the book. That's why the book should not be banned. That's why people should be able to read it and get used to understanding their own culpability.

Alison Stewart: That book is called 47 for those who would like to read it. The new book is Touched, out October 10th. Walter Mosley will be at P&T Knitwear on Sunday, October 8th at 2:00 PM. Thank you so much for spending so much time with us.

Walter Mosley: Well, thank you. I really appreciate it.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.