Walasse Ting's Radical Art

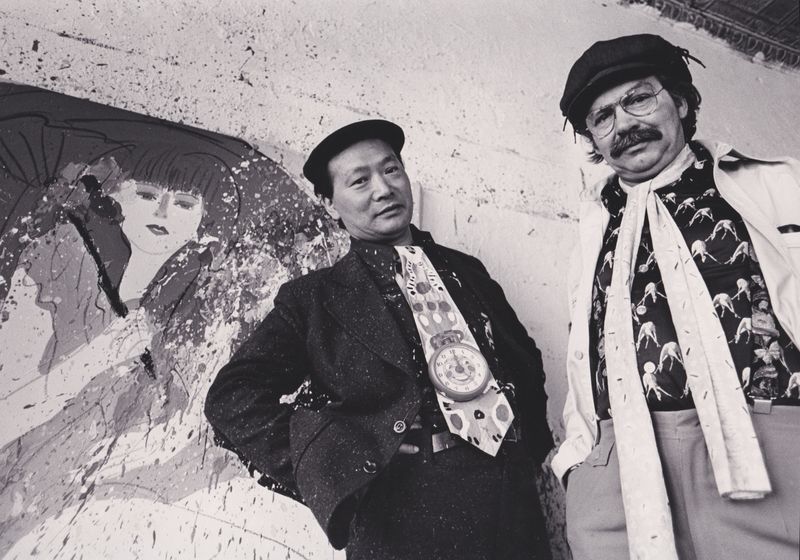

( Courtesy of The Estate of Walasse Ting )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. The brightly colored paintings of Walasse Ting are on display at the Alisan Fine Art Gallery on the Upper East Side. It's the inaugural show for the New York City outpost of the Venerable Hong Kong Gallery. The show focuses on the years that Ting spent in New York from the '50s through the '90s after his time as a young artist in Paris. Around 1958, Ting traveled to France from his homeland of China when he was 20-something with a dream.

His work is at the intersection of abstract and pop art, known for his neon-colored images of lovely women, as well as creatures like parrots and cats. They are instantly recognizable. The show also features some of his black-and-white work and splatter paintings, too. Walasse was a poet as well, and as one profile of my red noted, he ended one poem with this description of his practice, "Sleeping all day, living in a 60-feet window loft, eat there, paint there. Self-taught, individual, not belonging to any group." Joining me now are Walasse Ting's, daughter Mia Ting. Mia, welcome to the show.

Mia Ting: Thank you, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Daniel Chen, the director of the Alisan Fine Arts Gallery that recently opened at 125 East 65th Street, and the show is up through February 16th, I should note. Daniel, thanks for being on.

Daniel Chen: That's right, yes. Thanks for having me. Yes.

Alison Stewart: I want to talk about the gallery just for a minute. As I said, this is the inaugural show. Will you share us a little bit of the history of the gallery? Who started it? What's the focus?

Daniel Chen: Sure. Yes. The gallery was founded in 1981, so the two founders are Alice King and Sandra Walters, which is where the name Alisan comes from, Alice and Sandra. This was one of the very first commercial galleries in-- well, not very first, but it was an early commercial gallery in Hong Kong. The mission of the gallery was to work with and seek out artists of Chinese background, Chinese diaspora artists working abroad. Artists like Walasse Ting, which is why it's it's perfect that we are showing his work in the inaugural show here in New York. He was one of the very first artists that the gallery showed in 1986.

Artists who were notable, who had created these careers for themselves abroad, and the gallery wanted to reintroduce them back to their home country, being Hong Kong and China in general. Now, 40-plus years later, we are opening our first outpost here in New York and continuing this with the Ting Show. We plan to show also living artists, working artists, Asian American artists here, and continuing that legacy of the gallery.

Alison Stewart: Mia, what did you think when you heard that your father's work would be the first show in the Alisan Gallery?

Mia Ting: I was relieved and super happy. My father's original gallery in New York, Le Fab, closed in the 1980s, and he was never had another gallery show in New York after that. No gallery would take him. It was a really tough time. He concentrated back to his Asian and European roots and has had, I think, a certain level of success in both those areas of the world. It killed us.

I grew up in the West Village. I'm a New York kid, and this killed us that we weren't getting anything going on in New York. A lot of this started because NSU Museum, Fort Lauderdale, which I'd never heard of, approached me in early 2021 after COVID and everything getting canceled in Hong Kong about doing a museum retrospective for him. It was like manna from heaven falling after a year of hell and not being able to do anything. Then when Daphne King, the director of Alison Fine Arts in Hong Kong, that I've known almost my whole life, said, "I want to do something in New York," I was thrilled.

Alison Stewart: Sounds like it has been a really great past six months.

Mia Ting: Yes. It really, really has. I'm just hoping the momentum keeps going.

Alison Stewart: Mia, your father was born near Shanghai in the late '20s. I couldn't get if it was '28 or '29.

Mia Ting: It's '28. It's a fact, it was a mistake printed, and that it was '29 for decades. We've recently corrected that. We're trying to tighten up some loose ends, but yes, '28, year of the dragon, and believe me, he was a dragon.

Alison Stewart: We call those zombie mistakes around here. They just never die. They just keep going on and on.

Mia Ting: That's actually a really good term, I'm going to remember that one.

Alison Stewart: How did he describe his childhood to you?

Mia Ting: He was the youngest of four sons. It was Sino-Japanese War in Shanghai. He grew up in, I think, a somewhat privileged background, but also under the specter of war. He was sent to the country numerous times when he said that he would just run away or go back to the city because no one was paying attention to him. He always wanted to paint, he always wanted to go to Paris. Paris in the '50s was the place to be. It took a lot of hard work and scrappiness, but he got himself where he wanted to be.

Alison Stewart: Daniel, as Mia mentioned, he gets to Paris. He's in his early 20s. This is one of those, let me fact-check this because the the internet, is it true that he changed his name to Walasse as a nod to Matisse?

Daniel Chen: That is true, yes. He just loved the spelling. Yes, that's a nod to his favorite artist.

Alison Stewart: And he became part of a collective in Paris that spelled capital CoBRA.

Daniel Chen: Well, CoBRA. Yes. He was never part of them. Mia, you can jump in if you--

Mia Ting: He made a lot of extremely close friendships in Europe, in Paris. CoBRA was a group of artists that actually had disbanded by the time he met them, which was a collective of artists from Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam, hence the anagram. My father, he's associated with all these groups because he was very good friends with so many artists, including pop artists and abstract expressionists. He was very defiant in that he was not part of any group. His individualism was enormously defining for him. That may even been to his detriment in terms of putting him in some kind of historical context because he kind of floating all over the place within pop artists, New York abstract expressionists, and European artists.

Alison Stewart: What drew your father to New York?

Mia Ting: I think if Paris was the place to be in the '50s, New York was the place to be in the '60s, big time. He was invited here. He came and he didn't want to leave. He actually just took a ceramics class at the Brooklyn Museum to get a student visa so he could stay here. That's where he met my mother, who grew up in Crown Heights.

Alison Stewart: That's a story.

Mia Ting: That's a New York story.

Alison Stewart: That is a New York story. We're talking about Walasse Ting: New York, New York, it is at the Alisan Fine Arts Gallery. I'm speaking with Mia Ting, as well as Daniel Chen, director of Alisan Fine Arts at 125 East 65th Street. I'm going to ask you, Daniel, we're going to give our listeners a little bit of a tour, an audio-visual tour. In the first gallery in the museum, we don't see just his brightly colored work, but there are some splatter paintings as well. There's one called I Walk, I believe it is, from 1959. Why did you want to start the show with that work as well?

Daniel Chen: The layout of the show was the brainchild of Daphne. Daphne King is, I mentioned, the founders of the gallery. Her mother was Alice, or is Alice King. Daphne has been running the gallery for, since what, 1998 or so. She knew Walasse Ting. She knows his work through and through. She wanted to present, first of all, all works that were created here in New York. That's number one. Then secondly, she wanted to do something that was chronological.

We start, the painting you mentioned I Walk is from 1959, the year after he arrived here. I see these photos that Mia sends us of her father painting on the roof all the time. I'm sure this was one of them that was painted on the roof. Because they look-- there was action painting was very much happening here in New York. In that vein, he is using different materials to actually apply the paint and you see the motion, you see the energy, just this kinetic energy being splattered. We wanted to show some of those works before he came back to figurativism.

Alison Stewart: Mia, he painted on the roof.

Mia Ting: I think he even slept on the roof a lot. His studio had no shower, cold water, no kitchen. I think he picked that space in Chelsea because there was a Cuban coffee shop on the bottom. Yes, small space, so a lot of times, he'd paint on the roof.

Alison Stewart: He did become a New Yorker. What were, Mia, some of the traditions or behaviors or rituals your father had while he was working?

Mia Ting: He played music all the time, and it was a crazy mix of music. He'd have opera, he'd have classical. He would have Chinese music, pop, and classical, and then he'd have big band and Motown. You never knew what you were going to get in there. He painted every day, and I think that was a necessity for him just to be creative every day.

He wasn't the type of painter that had to be alone in his space. People would come over all the time. There was always coffee. There was always donuts. A lot of artists write about going to his studio, and I think a lot of them became interested in a lot of his techniques, especially Chinese ink, because nobody was really doing that here, especially in the 1950s.

Alison Stewart: If you go to the Walasse Ting Estates Instagram, there's a great picture of some paint-splattered black lace-up shoes. Did he always wear them?

Mia Ting: Those are his shoes. He had paint-covered shoes, paint-covered suits, because he always wore a suit. I think that's the Hong Kong upbringing. Those shoes are at the museum in Fort Lauderdale, NSU Art Museum in the vitrine. The curator, Ariella Wolens, who I kind of credit with all of this rediscovery of my father, she chose some really personal things to put on display for the show, which I think really give you an amazing picture of a person, not just the artwork.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing Walasse Ting: New York, New York, with his daughter Mia Ting, as well as Daniel Chen, director of the Alison Fine Arts Gallery. The show is up through February 16th. Someone texted us about my next set of questions. This person has texted. Can you talk about how One Cent Life was put together? So, Daniel, it's in the show. Would you describe what One Cent Life is and then, Mia, you can jump in.

Daniel Chen: I'll describe what it is. Yes, it's a book of lithographs. It was published in 1964, and in it, Walasse had published a few books of poetry. This is a much more involved book of poetry because it involved lithographs by a lot of his friends who happened to be some of the biggest names in contemporary art at the time. People like Karel Appel, Asger Jorn, Andy Warhol, Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell, Lichtenstein. The list goes on and on. There's 28 artists in the book. These were signed lithographs, and I believe the initial run was a book of 100 lithographs signed. We have a version. It's a reprinting here on display at the gallery.

I show everybody who walks in. I'm like, look at this artist list. How charismatic must this guy have been to be able to pull these people together from different crowds, too? The AbEx abstract expressionist crowd and the pop art crowd famously did not get along, but they're both well-represented in this book. How he did it, maybe Mia has some stories, I'm sure.

Mia Ting: It was not easy. Certainly. I know my father was even carrying proofs to different countries. A lot of the artists were in Paris at that time, so they could come in, but a lot of them weren't, and he was carrying proofs back and forth and whatnot. My father has always written a lot of poetry. He got this idea for this book. He got everybody to be in it.

It was really crazy, actually. It was edited by Sam Francis. It's a phenomenal work. I don't think you could ever get this many different personalities to do a project like this. I have to say, that book is pretty much in every museum's collection, big museum in the world. It's something he was enormously proud of and I'm proud of, but this has also, because my father's never enjoyed this recognition, the book is also kind of under the radar.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting. I love that one of our listeners knew about it without us even talking about it. That's great.

Daniel Chen: Yes, that's fascinating. It's been on view at several museums in recent years.

Alison Stewart: Is it a if you know, you know. One of those, that if you know, you know.

Mia Ting: Maybe.

Daniel Chen: Your brother said in one of these interviews I read that your dad lived by his code. How would you describe that code?

Mia Ting: Live life to the fullest. My father loved to eat. He loved people. He loved color. He loved hot weather. He liked flowers. I think he felt you should take all this good stuff in and then give it right back out, and that he did through his painting and a lot of his philosophizing.

Alison Stewart: Daniel, when people go into the show and they're expecting to see one of Walasse Ting's paintings using the bright colors, share with us one painting that really fulfills that mission.

Daniel Chen: One painting that fulfills that? It's called, I may get the exact title slightly wrong, but it's called Pretty Onlooker. What it depicts is a table. This is a motif that he came back to, but Mia was talking about food. It'll be a table laden with food. This is a big watermelon right in the main image. It's front and center. There's fruit. It's really colorful. Then right in the corner, there's one of Ting's what he's very well known for, this depiction of a woman. She's just looking from the corner at this spread. For me and for a lot of people, it just says it all. It has all these elements of what he's known for, the subject that he loves to paint. It's just about life.

Alison Stewart: Mia, how did your dad talk about his Chinese identity?

Mia Ting: He had a really Chinese identity. When my brother and I were children, China was foreboding. It was before it would reopen. No one ever thought you were going to go back. We couldn't even get anybody to teach us Mandarin. There was only Cantonese. He really held on to his Chinese identity, and I think as a lot of immigrants do, food, language, music, all these aspects stay with you, I think. I think when you're younger, you don't want to be the one who looks different than your friends and whatnot. To a lot of people, it may not sound like we look different, but in the '60s, we looked a little different even in the West Village.

My brother and I developed this huge fascination with China, which my father had kind of written off at that point and he told us we were of the roots generation, that we all wanted to know where we come from and had this fascination for it. I think when China opened up and my father was allowed back and we all went, it was really a very profound moment for all of us.

Alison Stewart: The name of the show is Walasse Ting: New York, New York. It is at the Allison Fine Gallery at 125 East 65th Street through February 16th. I was speaking with the director of the gallery, Daniel Chen, as well as Walasse Ting's daughter, Mia Ting. Thank you so much for spending time with us.

Mia Ting: Thank you, Alison. Thank you for having us.

Daniel Chen: If I have time to quickly mention, Ariella Wolens, the curator of the NSU Museum exhibition, is going to be here on January 27th with Mia giving a talk at the gallery. That's Saturday, January 27th, so listeners can come down.

Alison Stewart: Love that. Thanks for being with us. That's All of It for today. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening. I appreciate you, and I will meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.