The Ukrainian Museum Spotlights Contemporary Artist Lesia Khomenko

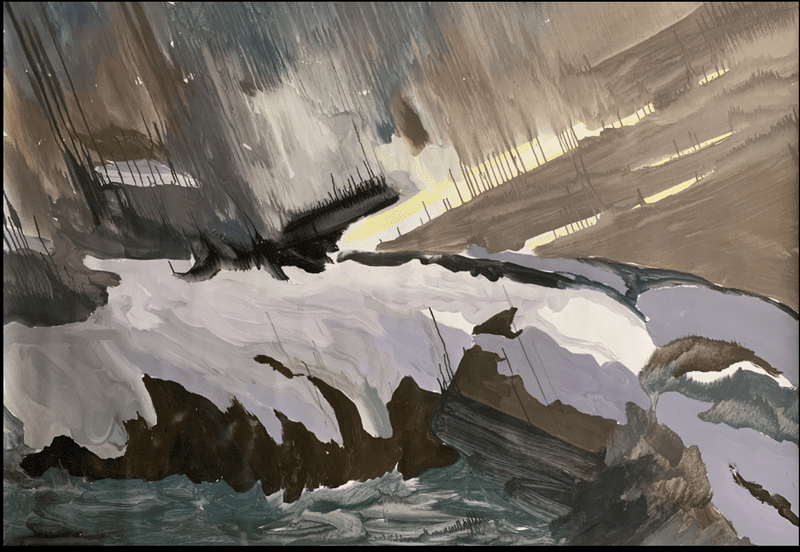

( Courtesy of artist Lesia Khomenko and the Ukrainian Museum )

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. Later in the week, we'll speak with author Victor LaValle about his latest novel, Lone Women. It's about a Black woman with a secret past who moves to Montana in 1915, lugging along a giant trunk with her. What's inside? You'll find out. The New York Times calls it enthralling and almost impossible to put down. We are thrilled that Lone Women is our May Get Lit With All Of It Book Club pick. Victor LaValle will join us on Thursday of this week to preview it. That is in our future. Let's get this hour started now with Ukrainian artist, Lesia Khomenko.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is the first week to see the work of Artist Lesia Khomenko, a Ukrainian artist who has been living in New York since March of 2022 after the start of the Russian War in Ukraine. This is her first-ever North American solo museum show. It is called Lesia Khomenko: Image and Presence, and it runs at the Ukrainian Museum now through September. The show features mostly new work from 2023 by the artist, but alongside pieces from earlier series, her earlier series going back to 2011. War is present throughout the exhibition reflecting Khomenko's own experiences and calling back to 20th-century Soviet painters who had lived through World War II.

Among the work is also a piece in dialogue with the art of Janet Sobel, the Ukrainian-American painter who moved to New York in 1908 and developed a style of drip painting decades before Jackson Pollock became famous. Has been reported that her work had an effect on him. Joining me now to discuss the exhibition in studio with me is Lesia Khomenko. Nice to see you. Nice to meet you.

Lesia Khomenko: Me too.

Alison Stewart: Also, joining us via Zoom is Curator Lilia Kudelia. Hi, Lilia.

Lilia Kudelia: Hi. Thank you for having us.

Alison Stewart: Lilia, why did you want Lesia's work for this multi-month exhibition?

Lilia Kudelia: Well, Lesia has been fantastically quick in producing very profound response to this very new type of footage, very painful footage that we, as Ukrainians, have to witness whether we are at home in Ukraine or dispersed everywhere in the world. Since the beginning of the war, Lesia launched also very important initiative for the internally displaced artists in Western Ukraine where many new, interesting works and exhibitions happened, again, very quickly in very turbulent times. We felt privileged for this opportunity to include the most recent work by Lesia as this immediate reflection to what we, as Ukrainians, collectively have to go through.

Alison Stewart: Lesia, what do you hope that people will come to understand and think about as they view the work in this show?

Lesia Khomenko: First of all, I would like to share my new approaches, how we could understand recent days, recent reality through digital war, so cyber war because I'm using a digital footage for my works, for my painting works. I think it's more global issues and only war in Ukraine. I think it affects all the world. I would like to speak about a new language and new understanding of humanity through my works.

Alison Stewart: Let me ask you about two new works created for the Ukrainian Museum. Is it Fragmented Surveillance and The Moment of the Shot? Could you tell us a little bit about the inspiration for these?

Lesia Khomenko: I'm using the footage from the internet, especially local Ukrainian websites, and books, and I found that photography now, photography documentary, photography and video changed their emissions, changed their role through this war because it's full of obscured pixelated elements and it's very secured, it's very anonym, but also it's very detailed so we could even walk on the death online.

Both these factors leads me to the idea that changing the role of photography and changing the role of working on our bodies. I'm using different footage with the most recent military technical equipments to look on the body through it like a type of monocular or, for example, drones or, for example, some on underlying video footage from battles. By working on it, I'm turning it to the material objects, to the painting to just point on specific kind of visuality.

Alison Stewart: Lilia, this may be Lesia's first solo show in North America, but she's been working as an artist for a long time. When you look at the full scope of Lesia's work, what do you notice about how she's working now as compared to, let's even say a decade ago?

Lilia Kudelia: Well, in this case, it's really interesting to be in the exhibition that Lesia proposed for the Ukrainian Museum because, as you already mentioned, we have works that date back to 2011, and that work was seemingly very different topic. The topic of how do we rethink the legacy of socialist realism as artists, for example, and how it impacted the thinking of the narratives that we grew up with.

What seems to be a very new approach for Lesia was this shift into abstraction. Had the traces and had the clues a decade ago when she was deeply embedded into the critical topics that even the museums, the institutions on an official level, didn't quite know how to grapple with and how to resolve those archives and how to present them through a more critical lens as this heritage, the burden of innocence that we have.

Alison Stewart: Lilia, has the focus of your own work as a curator and a researcher been impacted as we all have to adapt to the reality of the war?

Lilia Kudelia: It's obviously the only topic that feels important to be talked about these days. The need to decolonize so much context again on an institutional level and whatever we see coming from the artist studios is prevalent. I've been working for many years with artists from Eastern Europe, artists who witnessed wars in Yugoslavia, artists in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and not until now was I able to fully feel, comprehend the trauma and the pain that they are carrying within them.

On the one hand, it's this profound sense of kinship that I feel now with a way larger community of artists, creators, thinkers, and writers. On the other hand, it's also the feeling of trauma that keeps growing larger, but the hope that we can collectively create maybe new alliances and draw interesting historical parallels and understand our humanity better. The projects in collaboration with colleagues from the neighboring countries became also very important. I know that being in the US, and I lived in the US for 10 years, it's sometimes hard to put the topic of war on the agenda.

I'm also, working a lot in taxes. To a degree, I still feel invisible in this sense because there are way more other-- Here, we have to deal with the immigration, with other topics, but this reality started converging in a more intense way. It's not an easy task to deal with.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing the exhibition, Lesia Khomenko: Image and Presence. It's at the Ukrainian Museum. It just opened. It will be up until September 2nd, 2023. I'm speaking with the artist, Lesia Khomenko, and curator, Lilia Kudelia. There are two paintings, Javelin and Milan. They're in the same series. The name of the series-- I'm going to let you explain the name of the series.

Lesia Khomenko: Basically, it's a anti-tank missile gun, especially Javelin is very popular because it's widely donate to Ukraine by the US and it really works very successfully on the front line and it, I don't know, new kind of image of the front line battles. Also, it remind me tubes, just regular canvas rod in a tube. It's a very obvious object for me because I'm traveling over more than one year. Every month I'm traveling with troops in airports and trains.

This object partly it's about the war, it's about the murder of civil society and army because everyone donate now to army. I think it's very specific situation. It's very uncommon. In Ukraine, all people are donating or accumulating some money or volunteering for the army, but also in the US, also people work through their taxes. Paying taxes also support with weapon. I think it's very sensitive topic, but I think it's important to think about it in different ways.

Also, this rod canvas allowed me to deconstruct image itself, to turn the image to the object to the sculpture. Also, it's my biography of being in evacuation, being in immigration recently. It's a very concentrated, like a ZIP file image. Different meanings in one.

Alison Stewart: You use a lot of different mediums in this show. What is one that for you stretched you as an artist or challenged you as an artist? The kind of material you used, something that was like, "Oh, I want to try this, but I'm not sure I know what to do with this." [chuckles]

Lesia Khomenko: Basically, as media, I'm mostly working with a painting, but I understand painting quite widely, so I'm turning pictures to the objects. I experimented with materials. I think it's most challenging because painting is very clear thing. It's like in checkmate, you have only few figures on the desk and suddenly you in the next step. For me, about paintings always it's possible to invent something in very few elements in your hands.

Alison Stewart: Lilia, I want to ask you about one of the pieces titled AJS or After Janet Sobel, was in dialogue with a Ukrainian artist from the 20th century, whose work is also on view at the Ukrainian Museum. For those who aren't familiar with her, who was Janet Sobel?

Lilia Kudelia: Janet Sobel was born in Ukraine, then Russian Empire, what is now the Dnipro, in the end of the exhibition we'll also have large-scale images from the town that she, unfortunately, was forced to leave after her father was killed in the Jewish pogroms at the turn of the 20th century. She arrives to the US at 15 years old and doesn't become an artist until she's in her mid-40s after which she invents the dripping technique that, as you rightly mentioned, already influenced Jackson Pollock among other artists.

Janet Sobel will have a huge exhibition at the [unintelligible 00:12:31] collection next year, so Ukraine Museum is happy to present this project as a moving preface to a larger view of her work. It's interesting to witness how the history also spirals up and now having lesser-- displacing herself, maybe unwillfully from Ukraine, she comes to the US. I was thinking a lot about these narratives of ruptures, fragmented stories, the people who leave one environment and then re-socialize in a different society, and how important it is to lean to the narratives from generations before us and look for, again, for kinship, for understanding.

Having the work by Lesia Khomenko who quotes Janet Sobel and reflects on her legacy is extremely important. It breaks time in a way and it makes us spiritually stronger through the experience that we go through in any process of migration and displacement.

Alison Stewart: Lesia, why were you interested in having work and dialogue with Janet Sobel?

Lesia Khomenko: Once I heard that my show will be at the same time as Janet Sobel, I was so happy because it makes my experiments turning from figuration to obstruction. It makes new context, very important context of my practice in general because I was reflecting on a painting of the World War after World War II in the Soviet time, in the Soviet period [unintelligible 00:14:17] did this small paperworks during the World War II here in the US.

After this Syria that is presented in the museum, she turned to pure abstraction. These works are like pre-abstract works and this turn, this step before obstruction, it's extremely important to me because I think on this edge, on the trembling edge before obstruction is a lot of sense. I was trying to imagine how would I turn from pure works to obstruction. We know what she did, but I was experimenting with a figuration, with different methods on this my replica. For me, it was great chance.

Alison Stewart: I can say how happy you are when you talk about it. It means a lot to you.

Lesia Khomenko: Yes.

Alison Stewart: The name of the show is Lesia Khomenko: Image and Presence, it's at the Ukrainian Museum. My guests have been Lesia Khomenko and Curator Lilia Kudelia. Thank you so much. Thank you for coming to the studio. Lilia, thank you so much for being with us.

Lesia Khomenko: Thank you so much.

Lilia Kudelia: Thank you. Wonderful [unintelligible 00:15:28] together. Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.