The Story of Mother and Son, Afeni and Tupac Shakur Told in 'Dear Mama' Docu-Series

( Courtesy of FX )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on demand, I am grateful you are here. On today's show, we'll talk about the play Sancocho, with its director, playwright and star, a Latin tale of sisters with secrets, poet Eileen Myles is here in studio to discuss their latest collection and take your calls, and we'll talk about some spring cleaning. That's the plan. Let's get this started.

[Tupac Shakur's Dear Mama plays]

When I was young, me and my mama had beef

17 years old, kicked out on the streets

Though back at the time I never thought I'd see her face

Ain't a woman alive that could take my mama's place

Suspended from school, and scared to go home, I was a fool

With the big boys breakin' all the rules

I shed tears with my baby sister, over the years

We was poorer than the other little kids

And even though we had different daddies, the same drama

When things went wrong we'd blame Mama

I reminisce on the stress I caused, it was hell

Huggin' on my mama from a jail cell

And who'd think in elementary, hey

I'd see the penitentiary one day?

And runnin' from the police, that's right

Mama catch me, put a whoopin' to my backside

And even as a crack fiend, Mama

You always was a Black queen, Mama

I finally understand

For a woman it ain't easy tryin' to raise a man

You always was committed

A poor single mother on welfare, tell me how you did it

There's no way I can pay you back

But the plan is to show you that I understand

You are appreciated

Alison Stewart: There's a new five-part documentary series that takes its name from a song on Tupac Shakur's 1996 Platinum career and culture-defining album Me Against the World. In 2017, the original lyric sheet went to auction for $75,000. The third line of those lyrics we heard from Dear Mama "Ain't a woman alive who could take my mama's place." Tupac's mother, Afeni Shakur, was famous before her talented son became a world-renowned artist. She was a leader in the New York branch of the Black Party Panther-- Black Panther Party, excuse me, and known for her defense in court of the ultimately acquitted the Panther 21. More on that later.

Both were forceful people with strong wills and beliefs. Tupac spent his early years here in New York. His mother worked in the Bronx fighting evictions for people in financial trouble. They too had money woes. Tupac grew up poor and on the move. Afeni and her son relocated to Baltimore and then California, where Tupac would largely have to fend for himself due to his mother's drug addiction and learned to take on alter egos to survive all the way through his short life. The documentary features archival interviews with Pac and his mom, and it tells their story along with conversations with Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Mike Tyson, and family members of the Shakurs.

Joining me now to discuss the documentary, Dear Mama, which premieres on FX this Friday is writer and director Allen Hughes, and joining us in a moment will be executive producer Jamal Joseph, a former Black Panther party member and Tupac's godfather. Allen, thank you for coming in.

Allen Hughes: Thank you for having me, Alison.

Alison Stewart: This is not just a Tupac straight rock doc situation. It blends Tupac's story with a story of his mother, their backgrounds. Why did you elect for this framework, this sort of melding, this weaving of the two stories together?

Allen Hughes: What's the saying? The sins of the father, [laughter] and I'm like, what about the actions of the mother's and the thoughts of the mother? Because I was raised by a single mother, an activist mother who was out in the forefront of the women's movement. I related to that struggle and it was personal to me. Having known Tupac and worked with Tupac, it was personal to me. I looked at the icon around the world. You see murals of Tupac in Africa, South America, Europe, Asia. I'm like, "What's the meaning of it?" There was such a-- people project what they want to into Tupac. It's like no other 20th-century figure in that way.

You want to see a lover, you want to see a fighter, you want to see a poet, a philosopher, a saint, a sinner, you'll see whatever you want to in Tupac. I was confused by that and I wanted to understand him. I go, "Wow, maybe if I find out his mother's journey and excavate her narrative, it'll bring out who he is." Even more so, our mothers were greater than us. I just say that straight up, just the time they were in, knowing the brain that Afeni had and my mother personally, so that was the reason.

Alison Stewart: Tupac is-- his mother's no longer with us, she passed away at 69 in 2016. Obviously, he was murdered in 1996. The doc has music, lyrics from notebooks, archival videos. I mentioned that lyric sheet had gone up for $75,000 a couple of years ago. How involved was the estate in the making of the documentary?

Allen Hughes: Well, I will say that they were partners in that they granted me access and were always very helpful. I did ask that, let me please do my thing, or we just can't have rose-colored lenses completely here. Once I interviewed Glo, Afeni's only sister and Tupac's only aunt, she said it right out the bat-- I'm going to get my words straight. Right out the gate, she said Afeni wanted this story told, blemishes and all. There's a classy way to do that. They were really good as far as supporting-- because I was always asking for multi-tracks because I wanted the acapellas. I just wanted to hear him feel Tupac in different ways. They were very helpful.

Alison Stewart: You have to put the blemishes in the documentary or no one will believe you. [laughs] Honestly, right?

Allen Hughes: That's right. You know what? They both lived their life like that, the good, the bad, and the ugly, and that's probably why we're still talking about him and now talking about his mother. She lived her life out loud, not as loud as he did, [laughs] but that was part of it.

Alison Stewart: Hold on one second. I think Joseph Jamal might be here.

Allen Hughes: Ooh.

Alison Stewart: We'll slide him in in just a minute. We are talking about the documentary series, Dear Mama, about the lives of Afeni and Tupac Shakur. Episode one of the doc premieres on FX this Friday, April 14th. Tupac--

Allen Hughes: 21st.

Alison Stewart: Oh, I'm sorry. On April 21st. Let me get myself--

Allen Hughes: Next Friday.

Alison Stewart: Next Friday. We'll get people all excited. Tupac was politically active and a thinker, and the doc shows that if he hadn't gone to music, he could have easily been a politician or some sort of really big social activist. From firsthand experience, what was his gift as a communicator?

Allen Hughes: He had the ultimate power of spirit and moving a room. When he walked in a room, the temperature changed. That's called the it factor. That charisma, we all know, we've all heard about it with him. His sense of humor was off the charts. I think his emotional IQ, what do we call it? EQ now, or what is it?

Alison Stewart: Emotional intelligence.

Allen Hughes: Yes. Before we even had the word in the common day language, off the charts. He was empathic as well, which goes with emotional intelligence, I think. I don't think I-- and I've been around a lot of rock stars, stars, and pimps, hoes, you name it. [chuckles] I've been around a lot of colorful people, no one had the wattage he had and was steeped in the history and the struggle that he was. He was definitely destined to be a leader of social justice, some kind of leader in that area, but hip-hop came and derailed that plan.

Alison Stewart: He was also a really sensitive person as a young man, especially. There's a moment in the film when he, as a very young man, is thriving. He has to go to this art school, and he creates a movement piece to Don McLean's Vincent about Vincent van Gogh and how he relates to Vincent van Gogh in an amazing way. It's a very lyrical soft rock kind of song. Why did you include this story? It felt really purposeful to me.

Allen Hughes: Well, you're talking about-- that's right-center in the middle, part four and it's probably the central thesis on Tupac right there. He's an artist, pure and simple, full stop. Not a recording artist, not an actor, not a whatever. Like starts off just a pure artist. I think that's why he's no longer with us because sometimes those lines blur with artists, they don't know where reality begins and ends. You alluded to that in your intro about the alter egos, but that Don, Starry Starry Night's a very sweet song. I would shutter to call it soft rock. It's so sweet, right? [laughs]

Alison Stewart: It is sweet.

Allen Hughes: It's very soft and very-- Tupac had that side. He was very much in touch with his feminine and his sensitive side as well, and he wasn't ashamed of it. I think hip-hop made him conceal it as the years went on, that and the longing for a father figure. I think that there's a powder keg for someone that explosive, that artistic. When you have those abandonment issues and the displacement issues, and you're a pure artist, a pure poet, and you're very sensitive, highly sensitive, you see where that journey took us.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned Glo, Glo who is Afeni's only sister and Tupac's aunt. You can tell she's a truth-teller. She just tells it like it is. What questions did you want answered? Why did you think she would be a particularly good witness to this relationship?

Allen Hughes: Well, it seemed as though Glo was there since he was born and was there before, obviously, with her sister Afeni. I could see Jamal walking into the studio right now.

Alison Stewart: He's on his way.

Allen Hughes: I knew when I had dinner with her before we put her on camera, there was a mystical energy about Glo and her storytelling. She reminds me of an old blues man. She reminds me of Pryor sometimes at his best, Richard Pryor. It transcends and she's very, very frank and colorful. I knew. I'd go, "If this woman doesn't get nervous on camera, because you never know with civilians, we got a rockstar here." She did not disappoint. She's just unvarnished. To your point, when someone's being that frank, and that heartfelt too, and that loving, when the uppercut comes, you just appreciate it. You're like, "Oh my God, look at this."

She carries the film on her back. There are a lot of voices in the film, a lot of family and friends and whatever. I purposely made sure that we always came back to Glo, because she always centered the gravity of the picture, I feel.

Alison Stewart: Was there anything that she told you early on that really helped you shape the doc? Maybe you thought you were going down Avenue A, and then she says something and it made you stop and think, "Oh, maybe I should check out this Avenue B or C"?

Allen Hughes: She was frank about the poverty. I didn't know about the abject poverty. I thought they were broke here and there. She was frank. The biggest question I had for Glo was, "What's with all the moving with Afeni?" Because there's 13, 14, 15 to 20 different addresses all during Tupac's adolescence, maybe more? More cities than in New York alone.

Alison Stewart: Even within New York. You list off like, she was at Edgecomb. She's here, she's there.

Allen Hughes: You heard that?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Allen Hughes: Glo looked at me and she says, finances that she said in the film, but she says she was always struggling with addiction. I didn't know that. I thought it was just the so-called crack years. She had, you want to talk about postpartum really blues after that trial. There were certain men in the movement that went to prison. It's just a natural thing or got killed. Other of her comrades that were meant to be in that courtroom with her absconded and just left the country without her knowledge, broke her heart. She felt abandoned. I thought Tupac's abandonment issues were deep about the father stuff. You see in the film, they both had deep anger about the men in the movement that didn't cover them.

Alison Stewart: For people who don't understand what the trial is, would you explain that?

Allen Hughes: Ooh, I got to get Jamal to elaborate on, but the Panther 21 trial, the FBI brought a case against them, the City of New York. [unintelligible 00:12:40] What is the street?

Alison Stewart: [unintelligible 00:12:43] Street.

Allen Hughes: Yes, exactly. Where Tupac went for his assault trial as well to 21 of the Black Panthers for allegedly plotting a bomb, like major sites, all over New York. They were facing 360 years for that. Afeni defended herself, which is very bold. That was a revelation too. Talking to Glo was like, getting to understand what she said in that courtroom. Eventually, getting the words. Jamal can elaborate more about what that case was. They were not going to see daylight. That's just the bottom line.

Alison Stewart: She was pregnant at the time.

Allen Hughes: She was pregnant at the time of the whole trial. In fact, when they got acquitted, which is a miracle, by the way. I believe Tupac was born a month after the acquittal. A month and a half after the acquittal.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the new docuseries Dear Mama, which debuts on FX on Friday, April 21st. Jamal Joseph is in the building. We will take a quick break. We'll bring Jamal into the conversation. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guests this hour are Allen Hughes, a director, writer, and executive producer, as well as Jamal Joseph, executive producer of the new docuseries on FX, Dear Mama, about the lives of Afeni and Tupac Shakur. Episode 1 of the doc drops on Friday, April 21st. Jamal, you knew Afeni quite well and obviously Tupac too. Why is understanding Afeni's story, and how she carried herself, helpful in understanding Tupac?

Jamal Joseph: All of who Tupac was, was shaped by those early years with Afeni Shakur. Who she was as a woman, who she was as a revolutionary, who she was as a mom, and who she was as an artist. One of the things that we explore in the series is Afeni as a writer, as a poet. Whenever Afeni spoke, it was poetic. Whatever Afeni said to you had that imprint because it was like a verse. It was like a life verse. He grew up seeing that, hearing that, and being nurtured to have those revolutionary eyes and ears, and in that sense that we are not in the world by ourself. Afeni always made that clear.

Even when Afeni was struggling, they were doing work in the community around housing, around social justice, and all of those things. What's been great that we had a chance to tell the story and what Allen insisted on was that the relationship between them is powerful, symbiotic, and understanding them together helps us understand that generation. It's one of the reasons why Afeni and Tupac are relevant today because there's so many things that they encounter that they fought against, that they spoke on that are true some in Afeni's case some 50 years later, in Tupac's case, some 26, 27 years later.

Alison Stewart: How did Afeni Shakur become involved with the Black Panther party?

Jamal Joseph: Afeni was walking down 125th Street, and there was this guy on this podium talking about Black people needing to arm themselves from self-defense. He had swagger, he was charismatic, and it turned out that he was Bobby Seale, co-founder and Chairman of the Black Panther party. That was a moment. People talk about that Bobby Seale moment the same way that some people talk about that Malcolm X moment. Harlem in that corner was the place where everybody came and you'd go on a Saturday, see who was there, was part of walking down 125th Street. Then from there joined the Panthers and then met Lumumba Shakur, and quickly rose to a leadership position in the Black Panther party.

Alison Stewart: There's a part, I think where Afeni makes Tupac read the paper. What is she trying to give her son by making him read the paper?

Jamal Joseph: Well, she made him read all kinds of papers. It wasn't that he would just read the autobiography of Malcolm X, or Before the Mayflower by Dr. Lerone Bennett Jr. about history, she would make him read the New York Times. She wanted him to think critically. She wanted him to read well and to understand well. She's passed on the lessons. It's one of the first things that I learned from Afeni, and from the Panthers when I walked in the Panther office at 15, thinking they were going to give me a gun, and they gave me a stack of books, and we had to study. Those political education classes were the same. You had to be able to, as we call it, break it down.

Not only break down the Panther Ten-Point Program, but break down an editorial in the New York Times, and explain why that was working for against our folks. She wanted him to think critically. She understood as Afeni would say that the most important weapon that she could give him-- Tupac learned the martial arts and how to defend himself, but the most important weapon that he had as a young Black man was an armed mind.

Alison Stewart: Where do we hear that in his music, and where in his career did that become important?

Allen Hughes: That education?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

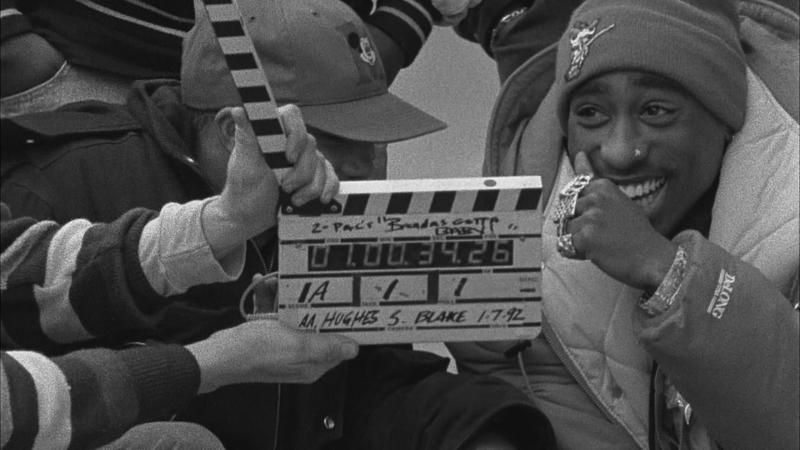

Allen Hughes: I think you see it early in his career. I think you see it in those first three albums. I think you see it in those songs that are, to this day, you don't see any male hip hop artists with Brenda's Got a Baby, with keep Your Head Up, with Dear Mama, and so on and so forth. There's just an understanding there. Then there's all the politics in this first three albums as well. All of that revolutionary stuff is coming out in those albums. I got to cut him some slack because going back to the abject poverty, and he says it in the film as a child. He says, "We were always poor because our ideals got in the way." I thought that was deep.

Alison Stewart: We would be rich if we were on our morals only.

Allen Hughes: Exactly, yes. When you're becoming a star and you look at the death row years, you got to give him, like-- let him give into the excess of a rockstar. That's what that was. We now know he had all these plans to come back to the social justice and the community. He was doing all that, planning all that. At 25, you got to live a little bit, too, so we should forgive him that.

Jamal Joseph: Afeni would, if you visited her, especially, visited the houseboat, and then she could look across the Bay and see Marin City. She would say, "Look where my son lifted me up and set me down at." What he did to help so many people quietly. That part we don't know. We see that at that moment where hip-hop went from a call out against oppression and police brutality to, we've made it, we've outsmarted you. When I was young, there was The Tales of Br'er Rabbit. Br'er Rabbit was the rabbit who always outthought and out-strategized people that was trying to kill Br'er Rabbit being the humans and the wolves. That sense of survival, surviving by our wits is what kept us alive as a people.

The different codes that we had to use to do it from the fields where those songs were songs of the underground railroad is coming to [unintelligible 00:20:54]. There's a part of that celebration that I am here, I've outwitted them, I've been shot, I've been in prison and I'm here, so let me celebrate that, that kind of swagger, but he never stopped giving in those moments. There's tales of so many people where Tupac helped with the rent or Afeni wanted to do something for someone else, that money was available and his idea was, I have to keep grinding because I'm grinding for all of these things.

Alison Stewart: That was interesting in the documentary, his almost inability to stop. That he slept three hours a night, that he was going from the studio to the video set, to the movie set, because he really wanted to be an actor. I was wondering as I was watching that, what would happen to him if he stopped. Would he have to face his demons, face his issues, face what's going on? That whole energy that was his success. I just kept wondering, "I wonder what would happen if this young man just stopped for a minute."

Allen Hughes: What's the Richard Pryor book, If I Stop, I'll Die?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Allen Hughes: Same thing.

Jamal Joseph: He had this sense though. Tupac told me when I would visit him in prison, that he was going to die. He was a artist, warrior, prophet, and like many people who have prophetic lives, he saw his death. The conversation he had with me about it wasn't if he was going to die, it was how he was going to die. He'd say clearly, "Look, I could go out like Tony Montana for Scarface, or I could go out like Malcolm X. I want to go out like Malcolm X." Of course, I as Panther godfather or Panther uncle, would go like, "Pac, people love you, you're going to be fine, you're not--" Then he wouldn't turn it into a debate whether he was right or wrong, or try to dissuade me from what I was saying.

He then, Allen and Alison, would immediately launch into his plans. He would start talking about the production company and the Powamekka Café, and how he was going to charge, these was his words, "All of these artists to give back to the community, to these youth programs." He had this vision of this national youth program that he was going to do. That would be his response when you tried to talk him out of the fact that he only had a little time left, is that he would just lay out all of the things that he had to get done and which part of it were you going to help him with.

Alison Stewart: It was interesting to see in the film also, just over the course of time, these, I think before you came in, we talked about his alter egos. That he was a different kind of person at different times. Sometimes even a little chameleon-like. When you think about his alter egos, Allen, how did they coexist and how did that affect him? It was really interesting even to watch his vocal patterns change.

Allen Hughes: Oh, wow, yes, you saw-- [laughs] Again, going back to the displacement issues and it's talked about freely, openly in the film about how he could blend into the lexicon of any neighborhood very quickly, and that's part of the coping skills of just adjusting quickly to whatever neighborhood you're now in and as an artist, back to the pure artist, he's taking in that stuff like a sponge. I think, like an actor, you start to feel a bit schizophrenic, I think. We all semi-live schizophrenic lives anyway, especially as people of color, but people in general, with your mother, with your lover, with your friends. It's all a different kind of face you show but his were extreme. I think that was weighing on him because the stuff you're talking about, Jamal, like those values were always there, and as he's seemingly losing himself to one of the-

Alison Stewart: Personas.

Allen Hughes: -roles or persona, yes, I think that was dogging him. You could feel it, you can see it in him. Even in the film, you can see it in his eyes. The responsibility, the one thing that you touched on that he never stopped doing from the time I met him, is he always was taking care of youth, friends, family. He was taking care of so many people, but before he had money, he was doing that. That comes from his mother, how she cared for people around her. I think that burden too, even though he was a giver, you can't help but to keep, when you didn't have the microphone, when you couldn't afford a microphone, when you couldn't afford anything to record on, once you get it, you don't stop because you are fearful of not having it again. That's another thing I believe that was dogging him. That's my personal opinion.

Alison Stewart: Well, when you spend a lot of time, it's an educated opinion. You spend a lot of time looking at all of the footage and context of his whole life and his mother's whole life. Jamal, when Tupac and his mother were not getting along, what was the source of the tensions?

Jamal Joseph: Tupac's disappointment and heartbroken that his mother was struggling. That the person who had been the constant and had been his hero had fallen. You know that poem when your hero falls, what are you to do? Afeni had that effect on Tupac. Afeni had that effect on me. Afeni remains to this day, my greatest hero from the Black Panther Party. I learned most of my lessons about manhood from Afeni Shakur. Not to take away the great mentors that I had in the Black Panther Party people like Dhoruba bin Wahad and Cetewayo Tabor and Sekou Odinga, people who were there to help raise me, but Afeni is the one that taught me about honesty and trust and values.

When Tupac saw that, that broke his heart. I think that he was feeling like I have to step away to protect me because the pain is so overwhelming. If that I'm too close, I won't be able to make it, but the instant that Afeni made a step toward recovery, he was there and they were reunited and they were stronger than ever. Afeni was able to come back with lessons from that journey of humility, of serenity, of understanding that you have to forgive yourself to move forward and be there to be that balance when things got really intense and really crazy in his life.

Alison Stewart: Allen, when did you first meet Tupac?

Allen Hughes: 1991. I was 19 doing our first music video. He hadn't become famous yet. His album hadn't come out yet. Juice was about six months from coming out. I met him at a Waffle House with Digital Underground and was instantly taken by that thing we talked about earlier, his charisma and his humor. Probably one of the funniest people I ever met. I met him in humor. To see seemingly go dark in places, was interesting because I think the joy and the humor was the strongest thing he had.

Alison Stewart: At some point in the film, you become a part of it a bit. What went into that decision?

Allen Hughes: To put it in the film?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Allen Hughes: We were looking at it, I didn't want to do it and my producers were like, "No, you got to deal with this because this is going to come up," and the network felt the same way. I go, "No, I don't-- It's false to do it." Then we found an organic way, one of his-- Atron Gregory, his manager, and Leila Steinberg, his first manager, were on the set and they go, "Well, what about--" you can see it in the film, it's actually going down in real-time. [chuckles] When I sit down, you can see I'm blushing because I say, "You know what? This is genuine." Because that was what I was trying to figure out. If we're going to do with this, I don't want to just show up on camera and start talking.

Also, Tupac's not here, so I had to let him fully exercise his demons about the situation, and I had to figure that line out and go, "Hey, you know what? I can't really explain everything I want to explain because it's not my place to and he's not here." That's what went into the decision.

Jamal Joseph: [crosstalk] If I can.

Alison Stewart: Yes, of course.

Jamal Joseph: One of the things that Allen and a key thing that Allen brought to the film was he honored what we know that Afeni would've wanted and what Tupac would've wanted, which is to tell the whole story unblemished as Glo says so poetically. It's so amazing how that rhythm and the way that Glo can read the back of a cake mix and make it sound poetic.

[laughter]

Jamal Joseph: Afeni had that same way, that little kind of in their voice, but unblemished. Afeni never wanted to edit the truth and Tupac didn't. I think one of the things that makes the series so powerful is that Allen really honored that in terms of the storytelling of it. Again, put himself out there too, just to say, this is an honest part of the story.

Allen Hughes: I got very, very prominent friends that go, "You made a mistake. Watch," and I go, "I made a mistake?" [laughs]

Alison Stewart: Well, the film gets into the arrests, it gets into violence that Tupac was a part of, and on the receiving end of. You really didn't leave too many stones unturned. What was something you wanted to get in the film that even though you had five hours, you didn't?

Allen Hughes: You know what? The thing that breaks my heart, and I think we'll get it in the book that's coming out soon, was there was a lot of things that happened in his adolescence. I'm talking about five, six, seven, eight, that we couldn't get in the film. There were some images that there was a person that owned them and was not being very agreeable. Jamal can elaborate on this. I thought I knew why he was paranoid. When I knew him, I thought I knew why he was paranoid all these years. I thought it was the weed. I thought it was the Hennessy. I thought it was the hip-hop lifestyle.

There's a story in the book, and I had to try to get in the movie. Being eight years old, Afeni wanted him to sit in the stoop and watch out for federal agents all day. That was his assignment. He blew the assignment and he was punished severely. I'd go, "He's an eight-year-old boy. Can you imagine that burden?" You know more about the details of what that was, but those type of things, we allude to them, but you don't get to see those things. That's my only regret, but we plant the seeds there. Baltimore is the thesis of when she's at her lowest and when he discovers his true gift. That became the core.

Alison Stewart: He seems so pure during that time. Some of that footage you have of him, he's just such a pure young man.

Allen Hughes: His drama teacher who's so well-spoken beautiful man, Donald Higgins. He says, when Tupac had to go to Oakland because his mother had to go and he's crying, he goes, "I was concerned that this was going to break the continuity." That's part of that run you're talking about with Starry Starry Night. You're like, "Ooh," that's very powerful.

Alison Stewart: It's a five-part series. It debuts on Friday, April 21st. It is called Dear Mama, about the lives of Afeni and Tupac Shakur. My guests have been Allen Hughes and Jamal Joseph. thank you for coming into the studio.

Allen Hughes: Thank you so much, Alison.

Jamal Joseph: Thank you.

[Tupac Shakur's I Ain't Mad at Cha plays]

I ain't mad at cha

I ain't mad at cha

I ain't mad at cha

We used to be like distant cousins, fightin', playin' dozens

Whole neighborhood buzzin', knowin' that we wasn't

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.