A Story About the Black Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis

[music]

Allison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Allison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us, and thank you to everybody who is in The Greene Space at WNYC. Donating blood as part of our blood drive with the New York Blood Center. Thanks to all of you who signed up and are coming down today helping to save lives. We're going to talk about right now a new book that also talked about women who save lives. People who save lives.

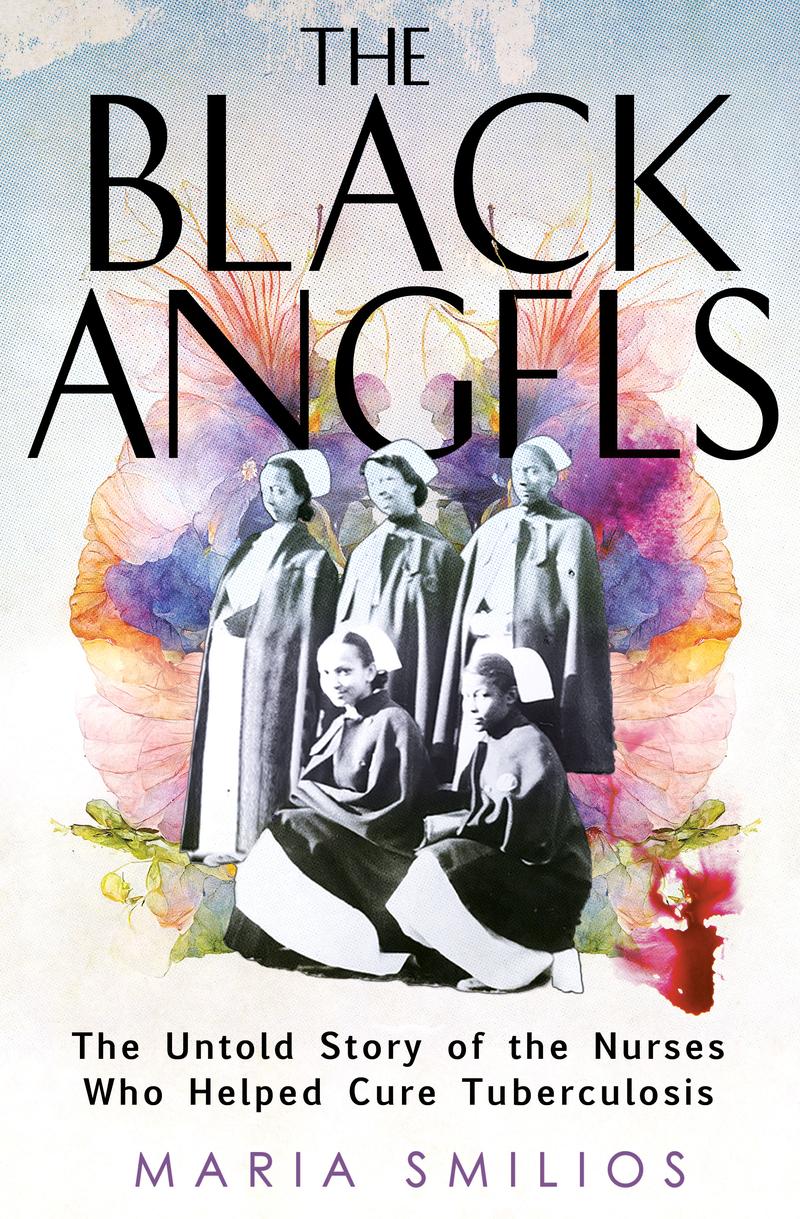

It pays homage to the African-American nurses often called the Black Angels, who served at Sea View Hospital on Staten Island, playing a key role in the fight against a disease, sometimes referred to as the white plague. The book is titled, The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis. We're introduced to our heroines in 1929 when TB killed one in seven people living in the US and Europe. In New York City, white nurses began quitting in mass due to the danger.

To solve the problem, city officials recruited Black nurses from across the nation, offering them housing, better compensation, and career growth opportunities. These women began treating some of New York's poorest and sickest patients, many of whom were left without hope waiting for death's release. Sea View Hospital shut its doors in 1961 but was later designated historical landmark in 1985. The Black Angel: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis is out now. Author Maria Smilios joins us to discuss. Maria, nice to see you.

Maria Smilios: Thank you for having me. It's nice to be here.

Allison Stewart: At one point, Sea View Hospital was the largest tuberculosis sanitarium in the nation treating thousands of patients. How did it become to be the site where so many people were treated, and who were the patients? What was the population?

Maria Smilios: At the turn of the 20th century, New York City was drowning in tuberculosis. At the time, one in three were dying of tuberculosis. The then Chief Medical Officer, Hermann Biggs, who was this real bulldog of a man wanted to conquer tuberculosis. He believed he could do it in a single generation and so he waged this war against TB, which is where we get this rhetoric of the war against TB, the war against consumption. What he did was he started to try and isolate the areas where tuberculosis had been the most prominent.

He did this through different methods. He used disease maps where he would send visiting nurses into the tenements. Down on the Lower East Side of New York were 80,0005-storey buildings where over 2 million people lived. At the time that was two-thirds of the city's population. He realized when these nurses would come back and report to him, "Oh, this building has this many people who are sick that certain clusters down there were what they called hotbeds of disease."

What he decided to do was target these areas. The thing with Biggs was that he also did not like the people who lived there who were predominantly immigrants. He also did not like the African Americans who were living up in Harlem at the time as well. What he decided to do was to present the city with this economics of human life. He said to the city, "These people who are getting sick are costing us millions of millions of dollars a year. Let's build a hospital and quarantine them on Staten Island." That is how Sea View got built. It opened in 1913. Within weeks, the hospital was filled to capacity.

Allison Stewart: Who worked there initially? Who were the nurses at Sea View initially?

Maria Smilios: Initially there were white nurses that were working there. They were traveling from the city to Staten Island. There was no bridge connecting Manhattan to the island. Their commute was long. It could take up to three to four hours round trip, sometimes longer. At the end of the 1920s, there were a lot of options for white working women for jobs that weren't killing them, and so they began to quit. Suddenly the then commissioner of Health, Shirley Wynn, was presented with a problem. Sea View had managed to bring the death toll down from 10,000 a year annually to 5,000 a year.

There it stalled, but it was okay because there were other measures being put in place. There was tenement reform happening. There were better sanitation. There was better sanitation in the city. When the nurses started quitting, Wynn became alarmed because he knew one of two things was going to happen. They would continue to quit, and then he wouldn't have a hospital staff and because of that he would have to shutter it. That would turn loose 1800 patients who were considered uncultured, uncouth, unrefined, "incorrigible consumptive," and the death toll would rise. He, at any cost, said it's not going to happen. It's just not going to happen. This is where this plan was birthed to start recruiting Black nurses.

Allison Stewart: What was the pitch to Black nurses? Think about it. Come work at this hospital full of people who might lead you to death's door. What was the pitch like to the Black nurses at the time?

Maria Smilios: It was done under the guise of a rare opportunity. They pitched it in the same way that recruiters who had gone down during the Great Migration-- The Great Migration was still happening, but at the beginning of the Great Migration, where they called up Black laborers and they lured them up with good wages, living conditions, employments, and an escape from Jim Crow. They said, "Well, let's try these professional nurses." What they did was they offered them a good salary, a steady job.

A lot of the nurses only had gone to training schools, so they were offering them education at the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing and of course a career. Here were these women who were stuck down south in the clutches of Jim Crow. They stood at a crossroads and they said, "Well, on the one side, we could stay down, for example, in Savannah or Mississippi and live within the confines of Jim Crow, or we could head north and wage our lives in a TV hospital, but at least there we have the opportunity for a career." They boarded Jim Crow trains and buses and came north.

Allison Stewart: The recruitment efforts coincided with the Great Migration. You write in the book many stories of Black women who had moved north told how they traded ambition for necessity. What sacrifices did these women have to make to create a life for themselves in the North?

Maria Smilios: Many of them left behind their families, their friends, the only community they had ever known. For example, Edna Sutton, one of my main nurses in the book, she was born in Savannah in 1900, and she leaves in 1929. It's 29 years of a community. She leaves her church behind. Her family has already migrated north, and she had been left behind with a younger sister, and she can't take her younger sister with her to New York City, so she leaves her with a brother.

They leave behind entire lives, and they come up by themselves to forge new lives, and new pathways to try and bring up their families, which many of them ended up doing.

Allison Stewart: My guess is Maria Smilios. We're discussing her book, Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis. Where did they live when the nurses came north? They came north by themselves as you said, without family, not necessarily knowing anybody here. Where did they live? What kind of lives did they have outside of the hospital?

Maria Smilios: Many of them lived in Harlem in boarding rooms that they rented. Some of them shared boarding rooms. A few of them moved into the nurse's residence as the white nurses started. They had a nurse's residence at Sea View. It housed about 200 nurses at the time. Some of the white nurses had lived there. As they started moving out, the Black nurses began moving in, but the hospital also began doubling in capacity. By 1929, the hospital had about 1,000 patients. By mid-1930, when the depression was really in full swing, it was almost up to 1600 in capacity.

They lived in these boarding rooms. They really didn't have lives outside of the hospital per se. They were working 14 to 16-hour days. Edna's commute was five hours from Harlem to Staten Island. They did go to church. They did join organizations, the NAACP and the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses. They were not, for example, going to work and then being able to go out to dinner and then the beach and whatever else somebody else would do if they were working a shift that was 9:00 to 5:00. This was not the way their life was structured in any way. It was all about the hospital, especially those who lived on the hospital often worked double shifts.

Allison Stewart: What was the daily life like for one of these nurses?

Maria Smilios: Let's take a life in the day of Edna. Edna was a surgical nurse. She would report to work at three o'clock. She would either depending on what her supervisor told her to do. If she was in the operating room, she would scrub in and do surgery, then she would do postoperative care. The nurses were also responsible for making sutures.

Sutures came, it was just a string of catgut and a little needle, a curved needle and they had to sterilize it and pass it through. They had to do gauze bandages. Gloves were washed and then dried, the gowns. Everything was sterilized. It's nothing like today where everything is just disposable. They set up the operating rooms, they sterilized the instruments, they took care of the patients depending on what kind of needs they had. Many times they also did linens and jobs that today nurses don't necessarily do. They're given to the support staff at the hospital.

Alison Stewart: Even though it wasn't the Jim Crow South, obviously, we're talking about the 1920s. There's discrimination in the north like everywhere else. How did these nurses-- what discrimination did they face?

Maria Smilios: Well, Sea View had a supervisor, Ms. Lorna Doone Mitchell. She was-- Let me just rewind a second. Most of the hospitals had white supervisors and only four hospitals in New York City hired Black nurses, the other 26 there weren't quotas the way they were down south, but there were gatekeepers who did not want Black nurses working alongside white nurses because they believed that white nurses would flee if they hired Black nurses. All of the overseeing staff were white.

Ms. Mitchell, who worked at Sea View, who was the Sea View supervisor, was the daughter of a Confederate medic. She came to Sea View to build up the ranks of nurses that had quit and her job was to train and retain a staff of strong nurses who would work in this TB hospital. She didn't like a lot of the Black nurses, it was the way she could wield her power. She didn't let them wear masks, she stalked them in the hallways waiting for them to do something wrong.

In 1937, the nurses walked into the new dining room and found placards that said whites only. She didn't allow them to transfer between hospitals. There were myriad ways in which today we would call them microaggressions, in which she taunted them and made their lives much, much more difficult than it already was dealing with really sick patients.

Alison Stewart: Was there ever a time when there was a flight of Black nurses who said, "You know what, this is not what we thought this was going to be," or did they stay?

Maria Smilios: No, they didn't have a choice. They couldn't leave. If they did leave, they would have to quit and reapply to one of the three other Black hospitals. Well, the other hospitals that hired Black nurses. They would begin again at a low wage. They'd lose any seniority or benefits, so they stayed.

Alison Stewart: My guess is Maria Smilio. The name of the book is Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis. In 1940, a 27-year-old doctor who's ultimately credited with finding the cure to tuberculosis in the '50s became the hospital's newest doctor. Tell us a little bit about him.

Maria Smilios: Dr. Robitzek came to Sea View as a celebrated doctor who had an illustrious future. It was shocking to people why he would want to come to this hospital way up on a hill in Staten Island instead of going to any other hospital that he could have gone to and worked. The reason he came was because his father had died of tuberculosis, and he came from a wealthy family. He saw how his father had been treated. His father was sent to Saranac Lake, and it struck him that there were a lot of health disparities, so he wanted to devote his life to finding a cure for TB.

He put himself in Sea View in the midst of the biggest municipal sanatorium in the city. He came to Sea View as a pathologist because he believed that you had to learn the disease internally before you could begin to treat it. Dr. Robitzek didn't really find the cure per se. The drug was developed by Hoffmann-La Roche. What Robitzek did was he facilitated the cure and the nurses executed it.

Alison Stewart: I was going to ask then, how did the Black Angels play into it? When did they come into the story?

Maria Smilios: In 1951, Hoffmann-La Roche called Sea View Hospital, called Dr. Robitzek. Actually, they called his partner Selikoff, and they said to him, "Hey, you know that drug we've been testing on mice? Well, it looks good. Do you want to test it on humans?" It had never before been tested on human beings. Two days of meetings ensued, "Yes," they said. Dr. Robitzek and Selikoff were put in charge of executing this one journalist called the most grandiose human experiment in medical history. The first trials for isoniazid on human beings.

The nurses were called in to work the front lines because they knew the ebb and flow of tuberculosis. Its nuances, they knew the arrogance of the disease, how it nod at the body, how it attacked the moods of patients, their psyche. It was called consumption. It consumed you literally, but it also consumed you holistically as well. They knew that one day somebody could be well and the next day they could hemorrhage. They also knew these patients. Most of the patients had been at Sea View for a minimum of a year, but many had been there three to five years. The first five trial patients were called "lungers."

One of the girls, Hilda had been there for five straight years. She was 20 years old, the criteria was death had to be imminent. The nurses knew Hilda, they knew her disease, they knew every time she came in and stayed a year and a half. What they did was they were tasked to administer the drug, and then they took all these meticulous notes, which at the end of the day, Robitzek collected and he went with Selikoff and they looked through them and they began writing downside effects. They saw how many patients had side effects and what the side effects were. They saw how it affected their physical being, how they started gaining weight. They saw their moods become elevated. This was all tasked on the nurses.

Alison Stewart: Where did you start your research for this? How did you start it? I know that for some of the documents, they're locked in a room somewhere, [chuckles], that you had to get access to.

Maria Smilios: That's a whole other story of getting access to those documents. The story of the nurses, I found it, I was working as a science editor, and I read the line, the Cure for Tuberculosis was found at Sea View. I became curious. When I found the article, alongside of it was an article about a woman named Virginia Allen. It said she was part of a group of nurses called The Black Angels, and so I became more curious about her, and I ultimately tracked her down. We began having these meetings in over a series of weeks. She told me a little bit about the story, and then she eventually asked me to tell the story. Then she told me there were no archives. There were no archives on the nurses.

This is an oral story, this is the story of years of talking with families and friends, and just sitting back as a journalist, listening decentering myself, and letting their voices structure the narrative arc of the story of the nurses. There were more archives of Robitzek because his son is alive, and he sent me his father's papers and there were newspaper articles. There was nothing in the newspaper about the nurses, not a mention of them. Nobody cared about their story.

Alison Stewart: I want to say Virginia Allen worked at the Schomburg for a bit.

Maria Smilios: She did, she volunteered at the Schomburg. Actually, she's still volunteering at the Schomburg.

Alison Stewart: That's amazing.

Maria Smilios: For, I think it's like 13 or 14 years.

Alison Stewart: I know sometimes when you write a story like this people start to come out of the woodwork with their own stories because they've only heard about it in their family. Has that happened to you? Have people been reaching out to you? Tell us a little bit about who's been reaching out.

Maria Smilios: I get a couple of emails a day. The last one I got was from a woman who said, "I think my great-uncle worked there." She had his name, and yes he did. I was able to look him up in the city records and send her some information. Most of the emails I get are really sad. There are people who say, "I think my mom died there." One woman said, "I think I was actually born there." Sea View was one of the few hospitals that had a maternity ward.

I've gotten emails from some white nurses who said, "This is a 100% true, I bore witness to how these women had been treated, and it's even worse than you talk about in the book." Then they describe these more horrible situations that happened. They come from all over the place, but it's really people trying to track down loved ones and verify if they were there. One person asked me if I could try and find out where their grandfather was buried.

Alison Stewart: Did these nurses go on to have long careers as healthcare professionals?

Maria Smilios: Yes, they did. Most of them died in their late 80s or 90s. When they worked themselves out of a job, essentially in 1961, some of them went into private care, others went into working in different hospitals. Virginia actually went into labor rights. She marched with Martin Luther King in the Civil Rights Movement, and she's still extremely active at 92 years old in her Staten Island community with voting rights.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis. My guest has been its author Maria Smilios. Maria, thank you so much for being with us.

Maria Smilios: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.