'Stiffed' Podcast on the Rise and Fall of a Feminist Porn Magazine

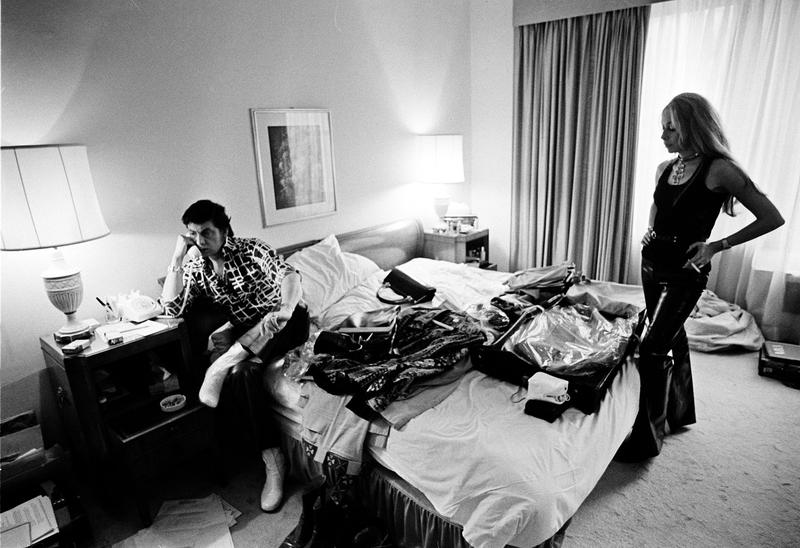

( AP Photo/Marcia Keegan )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Listeners, the heads up we want to let you know our next segment deals with adult themes. 50 years ago in 1973, a magazine aimed at stimulating both women's minds and their sexual fantasies arrived. It was a feminist erotica magazine titled Viva and its publisher was Bob Guccione, the brash showman behind Penthouse Magazine and edgy competitor to Playboy. Here he is from an archival interview that's part of the podcast stiffed about the founding of Viva. The first voice you hear is interviewer Christopher Glenn, then Bob.

Christopher Glenn: Since you started working in the area, "men's magazines," has your personal attitude about women changed at all? A lot of people say you're just an exploiter of women.

Bob Guccione: Well, they can say what they like. My attitude toward women if anything, has grown more respectful over the years.

Christopher Glenn: In what ways?

Bob Guccione: Well, I've come to understand them a lot better when I produced a woman's magazine some years ago called Viva, which was very successful with the readership.

Alison Stewart: Despite the DNA of its founding company, Viva attracted writers like Betty Friedan and Nikki Giovanni. Even though Guccione took credit, women were integral in its creation.

A new podcast called Stiff takes us from the unusual beginning, tumultuous middle, and ultimately end of Viva. In its review of Stiff, The Financial Times said, "At the heart of the series is the question of whether a magazine funded by a man who made his fortune exploiting female bodies could really change women's lives for the better. The short answer, it's complicated."

Stiff was named by New York Magazine as one of the best podcasts of 2023 so far. I agree. Host Jennifer Romolini joins us now. Jennifer, thanks for being with us.

Jennifer Romolini: Oh my God, thanks so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: You've worked in publishing at various magazines and you got your first copy of Viva from eBay. What did you think of it as a magazine?

Jennifer Romolini: Well, this is just this gorgeous, cool-looking, just really well-designed magazine. It's striking just as soon as you look at it. The covers were gorgeous. The inside design was gorgeous, but then as I was paging through that first issue, there were stories on art and artists, books, films, feminism, politics. There were in-depth profiles of people like Maya Angelou, along with a series of soft-focused male nudes. In a way, this magazine didn't make sense to me, but I was so intrigued by it because it was unlike anything I'd ever seen.

Alison Stewart: Was it initially, in part of its mission, was it meant to be an erotic magazine for women with full-frontal male nudity, a mirror of Penthouse, or was it meant to be something else, or a combination?

Jennifer Romolini: It was meant to be a competitor, I think, for Playgirl. I think that Bob Guccione, who famously hated Hugh Hefner and was competing with him the entirety of his life and career, saw Playgirl come out a few months before and said, "You know what? I'm going to keep pace with my nemesis." Playgirl was nothing like Viva. Viva was smart and vibrant and alive, and aspirational. Part of the reason for that was because it was staffed by some of the best female journalists of the '70s, female journalists and editors of the entire '70s.

The women who circled through that magazine went on to have careers for years, Molly Haskell, the famous feminist film critic, Patricia Bosworth who became a famous profiler and famous journalist, and wrote a lot of biographies including one of Montgomery Cliffed. Just a lot of really powerhouse editors, even though they were really young and it was many of their first job.

Alison Stewart: What opportunity did they see at Viva these women?

Jennifer Romolini: Well, for the most part, after the first couple of issues, Bob Guccione got out of their way. He was very interested in art and design and visuals. He controlled all of the pornography of the magazine, which is part of, I think why it failed because all of it was through a male lens. That's beside this point.

They were able to write whatever they wanted in the magazine. They were writing these very progressive ahead of their time stories on erotic fantasies, on the choice to not have children, open marriage, things that people were not really talking about yet. They had the freedom to write about it. They weren't getting that in other places.

I remember I spoke to an editor who had been at Newsweek before she went to Viva. In Newsweek, she couldn't even get a byline. They were getting to write these huge features and get all of this experience. We all know what it's like to make those kinds of choices in your career, like maybe I don't love the place but look at what I get to do.

Alison Stewart: Let's also time and space. Let's talk about 1973. How was Viva a product of its time?

Jennifer Romolini: Viva is a direct product of the sexual revolution. Actually, it mirrors the '70s almost perfectly. Sexual revolution, there's something that The New York Times coins porno chic. We have porn films in mainstream theaters, including movies like Deep Throat. That's the beginning of the '70s. Viva comes out of that. There's all of this freedom. There's all of this sexual equity. Women get to have desires, like men have desires.

As we go through the decade that begins to falter. The feminist movement splits in two. There's pro-sex feminists and anti-porn feminists. By the end of the decade when Viva ends in 1979, the [unintelligible 00:06:18] majority is coming in. Reagan is coming in. Everything is shifting in the culture. This was a really progressive moment in terms of sexuality. That's where this magazine comes out of.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Jennifer Romolini. She is the host of the podcast Stiffed about Viva Magazine.

Let's go all the way back to the beginning. Penthouse porn publisher, Bob Guccione was the person who at the beginning did all the PR interviews about the magazine, was the face of it, but it was this woman named Gay Bryant who first had the idea. We're going to play a clip from the podcast in a minute, but tell people who Gay Bryant was.

Jennifer Romolini: Gay Bryant was this aspiring journalist and editor. She's British. She had come up in this very flouncy women's magazine in London. Bob Guccione hired her to be an editor at Penthouse. She was the first editor of Penthouse. She moved from the UK to the US, didn't know anybody, and just gets her start really in pornography.

Alison Stewart: Then she has this idea, here's a bit of an interview with Gay Bryant from your podcast, Stiffed.

Gay Bryant: I began to think, gee why can't women who are now part of the sexual revolution and the women's movement and so on, why can't they have a magazine like this for them?

Alison Stewart: Gay Bryant suddenly had a magazine idea of her own and she shares it with her male colleague at Penthouse.

Gay Bryant: I went and talked to Ernie, the publishing expert there, and I said, "I think the company should do a magazine for women, a sexy magazine. It's time." He said, "Yes, great idea. Why didn't you write up a proposal and I'll pass it up to Bob?"

Alison Stewart: What happens next?

Jennifer Romolini: By the way, that proposal was 50 pages, and I think about that so much. She thought this magazine out. What happens next is she sees an article in New York Magazine where Bob Guccione is saying that he's launching a women's magazine. She had wanted to call it Mia. He called it Viva. It's just too coincidental for her, and she doesn't say anything about it at work, but she says something about it in this consciousness-raising group that she belonged to that Nora Ephron also belonged to.

Nora Ephron, after this consciousness-raising group where Gay is just ranting about a man stealing her idea, Nora Ephron calls her up and says, "Hey, I'm going to report that out that he stole this idea from you." Nora Ephron publishes a story about Bob stealing this idea from Gay Bryant.

Because of the time that it is and because of how women felt their place was in the workplace, Gay Bryant walks into Bob Guccione's office after this article is published that's publishing the truth, I think, and says, "I'm so sorry. I'm going to quit. I can't believe I betrayed you, basically." He stole her idea, but she quits the job. Of course, she felt so ashamed that she had gone against her boss, that she had been--

It really told me so much about the time when we had this conversation and she still feels a little bit of shame about it. She made a fuss. It's unbelievable to me.

Alison Stewart: She's also, and people might recognize because it is attributed to her, the phrase glass ceiling.

Jennifer Romolini: That's right. She's the first person to popularize the term glass ceiling. She went on to have this very rich and wonderful career in publishing and like many of the women, she's still working today.

Alison Stewart: Any startup has rough patches. What were some of the original challenges for Viva?

Jennifer Romolini: The biggest challenge was that Guccione would get out of their way, but then helicopter in or parachute in. He would just, "I know best." They were really trying to straddle this line between being really open about sex, but also being really honest about the limitations that they felt about sexual assault that was happening about safety. They were really trying to do a lot.

At one point, they did a package on rape and Guccione wound up firing the lead editor on this package because he was like, "This is an entertainment magazine. This should be a fun magazine." The startup costs were that the magazine didn't really know what it was and he wouldn't let them define it for themselves.

Alison Stewart: There was one point in the podcast, someone says that it aspired to be like Esquire ultimately. When you think about what got in the way of that, what do you think it was?

Jennifer Romolini: I think it was Bob. I think it was Bob Guccione getting in the way of that because he couldn't conceive of just this very smart magazine for women. I think also honestly, the male nudes got in the way because they were always clumsy. They were not erotic. They were not what women wanted. They were always through, like I said, the lens of a man.

At the core of this series is tracking the missteps of a megalomaniacal boss with inconsistent leadership style in a dysfunctional workplace. Who among us has not dealt with that?

Alison Stewart: Sounds vaguely familiar. We're talking about the podcast Stiffed. My guest is Jennifer Romolini. She is the host of the podcast. There are just all sorts of interesting tidbits in the podcast, facts in the podcast that really take you back to a time. One of the ones, and this is a little bit out of sequence, but I've got stuck on it, was the idea that you couldn't put Viva in the mail.

Jennifer Romolini: Yes.

Alison Stewart: That was a federal offense. Would you explain why and what impact it had on the magazine?

Jennifer Romolini: I'm going to be very careful about this because we're on public radio. I think I can do this. The obscenity laws at the time were that an erect penis was obscene, but a flaccid penis was not obscene. You could put Viva through the mail as long as you did not have an erect penis. That limited how the erotic imagery could be shot and what you could show clearly. I think that if we use a Seinfeld term here, shrinkage was a large part of this magazine, which, to women, was not always the most erotic. How was that?

Alison Stewart: That was really well done, re really well done. Our engineer thanks you. [laughter]

Jennifer Romolini: Thank you very much.

Alison Stewart: How did Viva run afoul of second-wave feminism? Everything you've described sounds like something that would be really welcomed. Women writing about women's issues, writing about just issues, writing about policy, writing about rape, writing about sexual assault, writing about aspiration Yet it did run afoul with certain feminists.

Jennifer Romolini: The Women's Liberation Movement starts in the '60s and it goes into the '70s. At a certain point, feminism became dominated by a certain fraction of feminists, which were the anti-porn feminists led by women like Andrea Derkin. What they believed was that porn of all types of any kind meant violence for women. It's just they equated porn and violence.

It was a very rigid point of view and if you participated in pornography of any kind, if you were a sex worker, if you were an exotic dancer, any of that, you were outside of the fold of feminism at a certain point. That starts about the mid-'70s and goes into the '80s.

The women who worked for Bob Guccione, who was a big enemy of these anti-porn feminists, even if they were putting out a progressive feminist porn magazine, were outside the fold of the movement at this moment. I don't think it was anything they did. I think it was simply their affiliation with Bob Guccione and that they were participating in the porn ethos generally.

Alison Stewart: When we think about how people viewed Viva and how people have viewed Viva in the course of its existence and looking back on it, it is very interesting, and my listeners might know this because I interviewed the woman who wrote the Anna Wintour biography, that Anna Wintour worked at Viva. She had been fired from Harper's Bazaar. She was this young, interesting sophisticated-

Jennifer Romolini: Ambitious.

Alison Stewart: -ambitious fashion editor. Why did they bring her on and what impact did she have on the magazine?

Jennifer Romolini: Anna Wintour comes into Viva at a time when it is just floundering for an identity. At a certain point, they decide that the male nudes are not worth it. They're not worth it because they can't get ads. A mascara advertiser doesn't want to be next to a full-frontal male nude. The magazine just can't make money. They decide to do away with the male nudes.

In doing away with the male nudes, they do away with their major subscriber base, which happens to be gay men, which is something that, of course, is happening because there's no other place to see full-frontal male nudity at this time. They do away with the male nudes. Now, they've lost subscribers and they haven't gained advertising money.

They bring Anna Wintour on to revive the fashion section of this magazine. They go from, I think it was, I forget exactly what it was, it was like 6 to 16 fashion pages overnight when Anna comes on and they think that she is going to legitimize them into becoming just a mainstream women's magazine. She has a lot of success there, but it's not enough to take off that sort of initial stink of it being a porn magazine.

Alison Stewart: The name of the podcast is Stiffed. I've been speaking with its host Jennifer Romolini. New York Magazine named it one of the Best Podcasts Thus Far of 2023. Jennifer, thank you so much for joining us. We really appreciate your time.

Jennifer Romolini: Thank you so much. The whole season's out now. Binge it. Have fun with it. Thank you for having me on.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.