Shirley Chisholm Gets Elected (Full Bio)

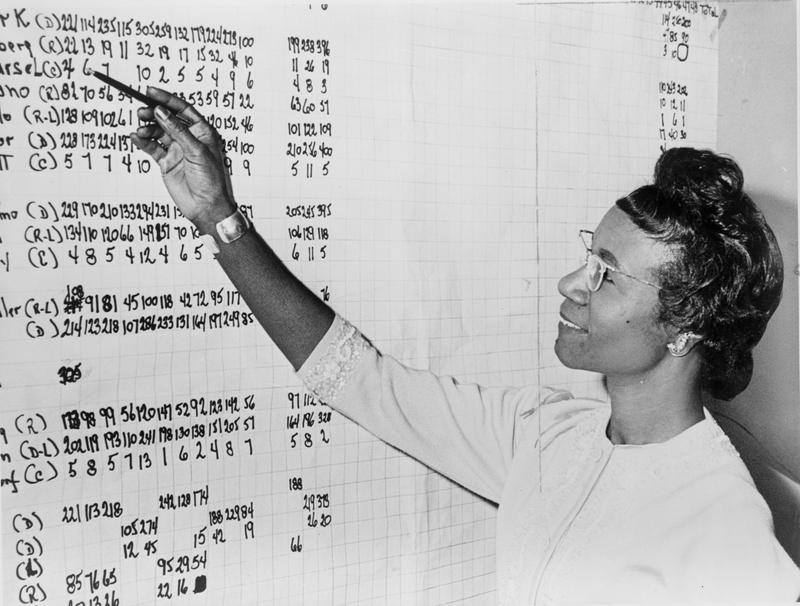

( Roger Higgins, World Telegram staff photographer - Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. / Wikimedia Commons )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thanks for spending part of your day with us. Later this week, we'll talk to Psychologist, Lisa Damour. Her latest book is called The Emotional Lives of Teenagers, and it aims to help parents guide their adolescence through challenging phases. We'll also take your calls on that. Plus we'll talk to Irish-born Singer, Songwriter, Hozier, on St. Patrick's Day, which happens to be his birthday, and play songs from his new EP.

A quick programming night, all this week at 9:00 PM, join WNYC for a special broadcast of the show Helga. Tonight, host Helga Davis talks with poet Claudia Rankin about who holds the power in our democracy, followed by a conversation with legendary choreographer, Bill T. Jones. That is in the future, but right now, let's get this hour started with Shirley Chisholm.

[music]

Alison: Full Bio is our monthly series when we have a continuing conversation about a deeply researched biography to get a full understanding of the subject. The book we are talking about this week is titled Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics by University of Kentucky Professor, Anastasia Curwood. Kirk has called the book, "A model political biography that all modern activists should read."

Chisholm was the first Black woman to be elected to Congress and the first Black candidate and woman to seek a major party's nomination for President of the United States, but before her turn on the national stage, she was a politically active citizen who realized she could make a difference with an elected position. Here she is from a 1969 Democratic National Club event, reflecting back on why she decided to leave her career in education and pursue a seat in the New York State Assembly, representing the 17th District back in 1964.

Shirley Chisholm: When the people in the district saw fit to ask me to leave the world of education and perhaps enter into the world of politics because during my spare time, I organized many groups, many organizations to appear before budget estimate hearings, city council hearings, and be the spokesman for the people in terms of the needs on the local level as they saw them. Pretty soon, it became noticeable that I never relented. That even though we may have taken trips from time to time to these various bodies, and we were received in a somewhat cold and aloof manner on many occasions, this never stopped me from telling them we will go back next week.

Each time I began to work in this way with the people in the district, the people felt that even though I was a professional person, that perhaps this was the person we really needed to function in the political arena.

Alison: From Chisholm's time in the New York Assembly, she said the work she was most proud of included securing unemployment benefits for domestic workers, as well as establishing a program called SEEK, Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge to help minority students succeed in college. It's still in place today at the City University of New York. Let's find out how it all started with Anastasia Curwood, the author of Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics.

[music]

Alison: Shirley Chisholm was elected at the State Assembly in 1964, and you write in your book, "She began to develop her brand of pragmatic radical politics." What's an example of a position or a priority for her that fits this description of pragmatic radical politics?

Anastasia Curwood: Well, the best example was her orientation toward women of color who worked and maybe were parents. She tended to look at politics through this lens, really throughout her 20 years of politics, that if these women who were at the intersections of parenthood, womanness, Blackness, they tended to be poor, that she looked at that intersection of vulnerabilities and really geared her policies and political interests toward mitigating those.

Now, that is a fundamental, so radical with the meaning of going to the root, that is a fundamental change in how political power is and was constructed at that time. That political power has been the province of men who were breadwinners of their families and seen as the true economic and political citizens. This is a very radical project that she's engaged with, but she's doing it through really pragmatic means of the party politics, New York State government.

She's working inside these political systems and she's also in those systems. She's not just going in and throwing bombs on the floor of the State Assembly, she's using very carefully reasoned speeches. She's creating allyships. One of the very first allies she made was Anthony Trivia. For her four years in the New York State Assembly, they didn't always agree, but she really kept him as an ally. You don't get much more establishment than the State Assembly speaker.

It's this blend of practicality and, "Okay, well, how am I really going to change how power works here? How am I actually going to put more economic and political power in the hands of these everyday moms who are trying to make ends meet?" I'm going to do it using the procedures in state government, and later, of course, the federal government.

Alison: What was one of her solutions? What was one of the things she prioritized?

Anastasia: Well, so what she was trying to do in the state, and then she expanded it into the federal government, was to get full protection, full labor protections so social security and minimum wage for domestic workers who tended to be an overwhelmingly be poor women of color, many of whom had children. She successfully did so both at the state and at the national levels. She hosted women who were seeking to change the New York State's Constitution to include reproductive rights, what we now call reproductive rights. She was trying to change New York state law to liberalize abortion. Now, the law that she was working on, the New York State Assembly was working on was much more of an incrementalist law than what Roe v. Wade created a few years later.

They were trying to get a bill passed that really left the decision to get an abortion between a woman and her doctor. It placed authority in the hands of physicians and women as we know, Roe v. Wade also took away the gatekeeper of the doctor.

Alison: My guest is Anastasia Curwood, the name of the book is Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. It's our choice for Full Bio. I want to give a little context for people about what the world was like when Shirley Chisholm was trying to establish herself as a civic leader. Her assent began around the time of the Moynihan Report titled The Negro Family: The Case for National Action written by Patrick Moynihan, then Assistant Labor Secretary in the Johnson Administration.

It was aimed at examining levels of Black poverty. It contained some problematic analysis, certainly as we look back on it, and even at the time, it was controversial, and some of it really rankled Shirley Chisholm, especially his take on Black women working outside of the home and contributing to the breakdown of the nuclear family. It's a two-part question. On a personal level, how did she feel about this? How did this affect her? Then on a perception level, the way people looked at her and talked about her based on some of Moynihan's assertions?

Anastasia: On a personal level, she found it really frustrating. She saw it for what it really was, which was a call for Black women to cede some of their self-determination so that Black men could get ahead. It believed that equality between Black men and Black women basically amounted to matriarchy. She, as somebody who thought that women were just at least as capable as men, it really wrankled her. She overheard some people call her the Black matriarch a few times during her political career and it really bugged her. I think the second part of your question-- oh, can you please tell me the second part of your question again?

Alison: I think you actually really addressed it, that idea that what Moynihan had put out there about the Black matriarch, some people began to assign to her.

Anastasia: Well, and it really plagued her career. It plagued her career later on. Some tried to use it against her in the 1968 election. It didn't work, but then there was suspicion, especially when she was running for president, that she was trying to take authority from Black men, and they were really mad about it. The Moynihan report really stung, especially for Black men who did not necessarily believe in women's equality or thought that women's inequality was a marker of status, because remember, this is a time before the feminist movement of the late '60s and '70s, it's just at the very beginning of it.

People really thought that women did not deserve or shouldn't have the same level of power that men should. They just didn't believe it. These men really thought that she was out of line and that did dog her.

Alison: This was a time when a woman, to get a credit card, needed her husband to sign for it.

Anastasia: Exactly. She thought that that was hogwash. I can sit here in 2023 and say, "How silly is that?" That's crazy, but this is the context that she found herself in, and it's pretty remarkable that she stepped outside of it.

Alison: You write that by the end of 1967, there was a movement afoot to elect a Black congressperson. Who else was in the mix? Shirley Chisholm was about to get into the mix. Who were some of the other names being considered?

Anastasia: Well, one of the major ones was a man named William Thompson, who was a sometime ally, sometime rival of Chisholm. In this case, he was a rival, and it was an open secret that he was supported by that local party organization, by the Democratic Party in Kings County. Even though they said that, "Well, we're not supporting anybody," that, "We're not going to support any anyone candidate."

That's actually where her slogan unbossed and unbought came from because she thought that the Democratic Party facilitated the buying of candidates through the trading of favors and patronage. That the boss, when you're boss, it's the party boss who calls the shot, says when you can run and what you could do when you run, and how you should run, and because she didn't have the support of the party, she didn't really have a choice, but she embraced it.

She said, "Oh, okay. Well, fine. I don't owe you anything." William Thompson, on the other hand, he owes them a lot. She was one of-- I'm trying to remember if it was 8 or 12 possible candidates who were interviewed by the committee to elect a negro congressman from Brooklyn in the aftermath of a redistricting case that the Liberal Party of New York brought, actually, to get the district redrawn. It was gerrymandered, like other districts we have today.

It was gerrymandered and the largely Black population of Bedford Stuyvesant was split up in four or five different ways so the voting power was really diluted. When that redistricting was in the works, this committee for a negro congressman started interviewing candidates, she said she was chosen because she talked back to them and she told them the truth, and she was honest, and they liked that she wasn't obsequious.

Maybe so, or I think some other people say, "She just was the obvious choice. She's in the state assembly," and, "We know she can run a good campaign," [chuckles] but either way, she got the nod and she was put forward by this organization, so she already had some support behind her.

Alison: Her headquarters was at 1103 Bergen Street, near Nostrand Avenue. I think it's a community garden or it's a lot now. She kicked off her campaign on January 19th, 1968. What did she have going for her as a candidate, just objectively?

Anastasia: Well, subjectively, she had some grassroots support in the heart of the district. She's also running under the Democratic Party which was dominant in the district. She had the key women's organization that she was part of that supported her and Black women, in general, were her most stalwart supporters through her entire career, and especially through the presidential run. She had Black women who really cared, who were really devoted to her. She had labor unions and labor support. Also, she had Mac [unintelligible 00:16:36]. They'd made up after their split when she tried to take over the Bedford Stuyvesant Political League. It's not clear who called whom, but one of them called the other, and they got back together, and so she had his political mind.

One of the things that he identified pretty early was that the district was largely female, it was three to one female in terms of registered voters, and so that was a bit of an ace in the hole for her. In fact, she was replacing a woman, the previous district, it was not drawn the same way, but the previous district had been held by Edna Kelly, who was also a woman. She knew a woman could get elected and she knew that there were a lot of women voters.

Alison: We knew who she could count on, we talked about women. Who did Shirley Chisholm need to woo in this congressional race?

Anastasia: [chuckles] It's really interesting. The folklore about this is that it was a Black district, and that a Black man, Andy Cooper, successfully sued to get the district redrawn. That's actually not true. It was the liberal party and the district was about 50% Black. There were a lot of white people in that district, and she had to woo the white people. She had to woo women, white women, she had to woo Jewish people.

She went to white neighborhoods and sat down with them, talked, had coffee, endless cups of coffee, and she really spent time in neighborhoods that were majority white. We think of this as, "She won this Black district and a Black person was definitely going to win." Actually, maybe that was the case because Black people were the ones who were running, but she had to win over the white people.

Alison: We'll have more of my conversation about Shirley Chisholm's campaign with Biographer, Anastasia Curwood, after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. We continue our Full Bio conversation about the book, Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. On January 19th, 1968, Shirley Chisholm officially kicked off her campaign to represent the 12th District of Brooklyn in Congress. She ran on the idea that she would provide local leadership and was a homegrown candidate. Her platform included in her words, "Decent low-cost housing, equality, education for our children, extension of daycare facilities and federal support for these centers, adequate hospital and nursing home facilities, enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, and an increase in tax exemption from $600 to $1,000 dollars per person."

Chisholm said of her neighborhood, "We have never had anyone looking like us to consistently and persistently hammer away at these matters." Let's get back to our conversation with Anastasia Curwood.

[music]

Alison: I want to talk about her campaigning a little bit. She would be in a truck that would go through neighborhoods and announce that she was the fighting Shirley Chisholm. Why was this a good position for her, the fighting Shirley Chisholm?

Anastasia: Well, first of all, it was who she was. She was pretty feisty, so it fit. She could pull it off because it was true. She was telling people that she was fighting for them, that she was taking on establishment politics. She's from this insurgent party. She is not beholden to the party bosses and she's doing things a little bit differently. She had this populist flavor and people liked the idea that she was fighting for them.

This was how campaigns were conducted, anyway, that people got in sound trucks or sound cars, and they put a loudspeaker on the top and drove around and they just talked. If that happened now, it'd be like, "Wow, that is weird." You imagine would be, "They're unhinged. That's too tacky. We're not going to go for them. That's tacky." That was what everybody did and that's what she could do. Then she'd get out on a street corner, and she would see and talk to people there, and she'd give a little speech and a little rally and she'd move on. That maverick image that, "I'm going to fight for you. I'm not going to fight for these old crusty guys sitting in their clubhouse," it worked for her.

Alison: I'm glad you brought up the old crusty guys because it becomes very clear that sexism is going to be one of her biggest obstacles. You even write about how some local ministers wouldn't support her. How did Shirley Chisholm get around these archaic thoughts about women in leadership roles?

Anastasia: Some of it was spoken and some of it was unspoken so she'd say, "Well, don't say that I can't do this because I'm a woman." She said that overtly, many, many times. "Would I be getting this kind of trouble from so and so if I was a woman?" Also, implicitly she talked to women, the Emma Lazarus Club in Brooklyn. There's some really wonderful audio footage that the Schaumburg Institute has and the New York Public Library. She addresses the Emma Lazarus Club because she says, "These women are important. These are the women I need to be talking to," and other women's groups.

Then also, you need to remember, this is radio, so we can't show pictures, but Shirley Chisholm was a close horse, very feminine one. One of the people who worked for her later on Capitol Hill called her a feminine cupcake with the heart of a lion and very solicitous as well, very charming. She is disarming. She's saying, "I can be feminine, I can be a woman and I can still do this. Don't say just because I wear a skirt, I can't do this." I think that she, in some ways, charmed her way into office and was very strategic about the self-image that she presented.

Alison: When she would go on these tours and these sound cars, what did her potential constituents tell her was important to them? What were the people telling her?

Anastasia: That's a good question. I don't have much of a record of what people told her on these trips except what she got reinforcement for was talking directly to them. Sometimes, that was in Spanish. She'd speak in Spanish and get applause, and so that was reinforcing. Sometimes, it was money. One of the smaller donations she got, she said was the most meaningful to her. She told this story a few times in different interviews and in her memoir, that some Black women showed up at her door early in the campaign and had a tiny donation at $9.42 or some small amount like that, and that they handed it over to her because they thought that it was so important that she run and that she win.

She said that the kind of interaction where somebody kind of gives her their hard-earned money, the money that they really couldn't spare, she said that was energizing and also a little bit intimidating. Well, she didn't get intimidated very easily, but it's about as close to intimidated as she would get that, "Okay, I really have to produce for these people. These people want me to run. I have to give it my best shot for them."

It was the faith of voters that seemed to be the strongest spur to her continuing and working in politics. It even worked when she was considering retiring from Congress that somebody told her, "You really give me hope and your presence in Washington is so meaningful to me." She said, "Okay, well, I can't retire now. I've got to be there for these people." It was that sense of responsibility that people transmitted to her that I think had the most impact.

Alison: My guest is Anastasia Curwood, the name of the book is Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. It's our choice for Full Bio. During her campaign for Congress, she would have a health scare that would become an issue that would lead to her inability to have children. She was already very small. She was a thin woman. Her health was greatly impacted. What impact did it have on the campaign when she felt ill?

Anastasia: Well, so to her, on a practical level, she didn't want it to have an impact on the campaign. She wanted to keep going, but she had benign tumors and had to have a hysterectomy. The rumor got out that she had cancer and that she was dying. The doctor said, "Look, you need to recover from this." This was before we had these robotic surgeries for women to get hysterectomies. She was really supposed to just lay low but she started hearing these rumors that she was dying. She's like, "I've got to get out there." She said she told her husband, Conrad, that, "The stitches are not in my mouth. I can go out there. I can get in that sound car. She wrapped a towel around her waist so her skirt would fit properly. She got in that sound car and she went out again and just kept talking.

Yes. It was very scary because they didn't know if the tumors were benign or malignant before the surgery, and it was a major abdominal surgery, so it took a lot out of her. She lost a lot of weight. Her problem tended to be when she was stressed, she would lose weight. That's what happened to her. As it turned out, it happened in-- The timing worked fairly well. That she was diagnosed at the beginning of the summer. She had the surgery. She was able to go and be at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the one in Chicago that was really chaotic. She wasn't quite 100% back up to speed, but by late summer, she was getting out in that sound car again. The timing, actually, it could have been worse and she did keep going.

Alison: Who was Shirley Chisholm's biggest competition and why did she ultimately win the race?

Anastasia: Her biggest competition was James Farmer, who was until recently, the National director of the Congress on Racial Equality Core, he's famous for starting the Freedom Rights, famous for having some of the first sit-ins in Chicago in the 1940s. Really one of the big four civil rights groups. Really big deal. He was not able to run. He had no entry into the Democratic Party in New York. He ran on the Liberal Party ticket and on the Republican Party ticket.

It's important for listeners to know that, yes, this was compatible in 1968, that New York liberal Republicans had a good bit of influence in state and eventually, in national politics in the form of Nelson Rockefeller. He ran on that ticket and everybody thought, "Oh, he'll win because he's famous." He wasn't that famous in Brooklyn. He was living in Manhattan. Finally, he was running his campaign. His campaign literature said that he would be a strong man's voice in Washington for the district. The district was three to one female voters. That strong man's voice in Washington,-

Alison: Wow.

Anastasia: -it might work with some women, but there were plenty of women who thought, "Maybe, it's time that we have a woman's voice in Washington." They voted for Shirley Chisholm. The fact that he was a carpetbagger. He was from over the bridge and not from the district, that he tried to use that masculinist rhetoric, and that he wasn't in the Democratic Party. All those things helped Shirley Chisholm.

Alison: How did Shirley Chisholm think about her status or view her status as the first Black woman elected to Congress?

Anastasia: First of all, she was very proud. She liked being a first. She liked achieving, even though she wanted to be remembered, as she said, as a catalyst for change, as somebody who really made a difference. Inasmuch as she was this historic first, that was a source of pride. What's important is that she wasn't just the first Black woman in Congress, she's the first Black feminist in Congress. She has an unprecedented platform with which to advocate for Black feminist ideas. Going back to that bedrock idea that she had of protecting folks who are the most vulnerable, protecting, for example, Black women and women of color who were trying to make lives for themselves and their children on poor wages. Those are the people who were at the center for her.

Those people had never had someone put them at the center in Congress before. She really took up the mantle of trying to advocate a larger purpose. Yes, the 12th District of New York, but also her being a Black woman was at time secondary to the fact that she wanted to advocate for Black women if that makes sense. Now, what she does say is that she got some flack. She got a lot of attention as the first Black woman. She says that her Black men colleagues sometimes resented the attention that she got.

Alison: On tomorrow's Full Bio, we'll discuss what Congresswoman, Chisholm, was able to accomplish and how she managed to get around the myriad obstacles in her way.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.