Richard Avedon at 100

( ©The Richard Avedon Foundation Courtesy Gagosian )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. The highly anticipated exhibition Richard Avedon 100 just opened at the Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea. Born May 15th, 1923 in New York City, Avedon made portraits that are almost instantly recognizable as his, the contrast, the energy. In this show, you can see the revealing details he captured in the faces of people like Patti Smith or Linus Pauling.

He playfully posed a high fashion model in a Dior dress with her escorts, two elephants. Avedon famously once said, "My photographs don't go below the surface. I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues." While his 2004 New York Times obituary led with his surface and fashion work declaring Avedon, "Helped defined America's image of style, beauty, and culture for the last half-century."

He also photographed the very real struggles of incapacitated people in psychiatric care, as well as the civil rights movement, as well as world leaders. This show could have just been a greatest hits. Instead, the curators asked some of his subject, his family, his inspirees to choose the photos. For example, music producer Mark Ronson chose Stephen Sondheim's portrait.

Director Ava DuVernay chose a photo from 1949 of a random little boy in Harlem strutting across a playground with a lollipop in his mouth. Avedon 100 is at the Gagosian Gallery on West 21st Street until June 24th. Today we're joined by James Martin, executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation. James, hello.

James Martin: Hi, how are you, Alison?

Alison Stewart: I'm doing well. Also joining us is art and cultural historian, Harvard professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, who before joining the faculty, held curatorial positions at MoMA and the Tate. She chose one of the photos in the exhibition and wrote an essay, which is in the accompanying book, Avedon 100. We'll keep it a secret until we get to later in the conversation. Welcome, Sarah.

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: Thank you for having me. It's great to be here with you.

Alison Stewart: James, you worked with Richard Avedon. How did you meet?

James Martin: I was an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, working on a project in the photo archives there when I happened to run across Avedon. He was working with his negatives, going through them and making his selection to choose which ones that he wanted to take with him back to New York. In Arizona, at the Center for Creative Photography housed many of his photographs and his negatives as well. He spent about a month there. We worked together, and he asked me to come to New York to be his assistant.

Alison Stewart: Avedon was known for his work ethic. He even passed away when he was on assignment for The New Yorker. What motivated him? What drove him, James?

James Martin: Curiosity. I think that underscores the whole exhibition that we're putting on right now. That's that curiosity of who his subjects were, what predicaments they're in. It's a curiosity that drove his interest, even his early days in fashion to his portraiture of unknown and uncelebrated people in the American West in the 1980s.

Alison Stewart: Sarah, you wrote in your piece, "The time is always right to celebrate Avedon." Why do you believe that?

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: For many of the reasons that James said and more. We are really in a moment where we're redefining our understanding of how images construct and give us a chance to remedy the narratives that define who counts and who belongs in American society. Avedon is exemplary in offering us a way to think through the impact of images and culture to do precisely that in this moment. His work offers creative models, I think, for artists of all kinds, as does his rigor and imagination in the construction of each image.

Alison Stewart: James, when did the idea come about to have photographs taken by various stakeholders as opposed to, like I said, it could have been a greatest hits and everyone would've been pleased.

James Martin: Laura Avedon, the daughter-in-law of Richard Avedon came up with the idea a few years ago. Rather than having central curators that have their own vision of who Avedon is, she came up with the idea of asking at first 100 people to vision their own Avedon, which is interesting because we had a lot of fear that people would pick the same three or four photographs, but actually, that's not the case.

Because as it turns out, everybody that we asked had different ideas of who Avedon is. Is he a photographer that primarily works in fashion, and do you look at his early work in the 1940s, and certainly, you could do an entire retrospective of that work? Or do you want to take a closer examination of his work with James Baldwin in the Nothing Personal period where you can take a look at a vast body of work that covers his civil rights interests?

You take a look at his later portraits of celebrities, of people of importance that he photographed for The New Yorker. These visions, these ideas of Avedon, when you pull them all together from each individual subject, creates a larger retrospective that we can see his entire career.

Alison Stewart: Sarah, you are involved on two fronts as the art historian, but also you chose one of Avedon's images for the exhibit, but it's also one that is part of an initiative called Vision and Justice of yours. Before we reveal that photo, can you share the work of Vision and Justice?

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: This is a project that's really focusing on research and academic programs and public-facing ones that really allow us to think through how culture has allowed for us to reshape the visual environment, to foster equity and justice in the United States. The issue, the aperture, commissioned being the guest edit became the first launch of the Vision and Justice Project in 2016. That issue had two covers.

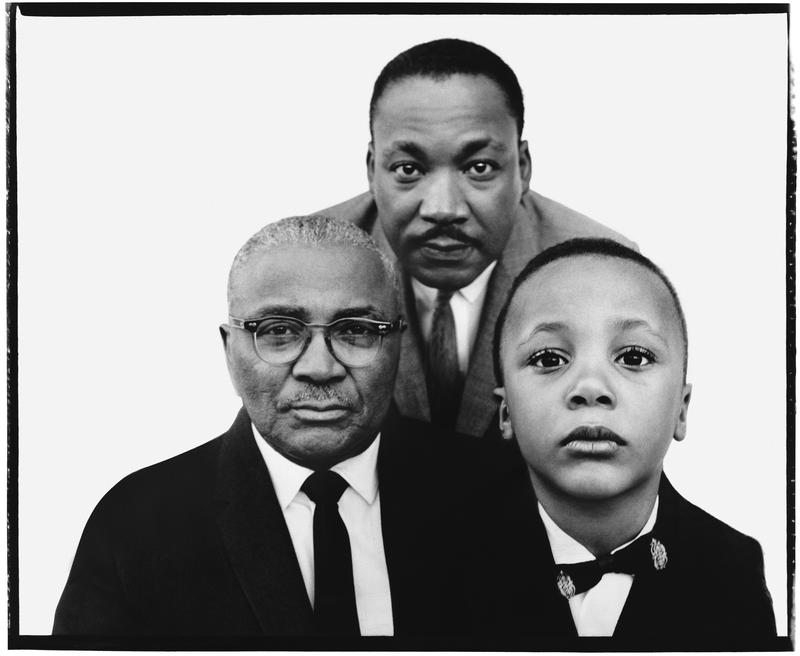

One, created by Awol Erizku, a wonderful photographer, and another I was fortunate enough to be able to use was by Richard Avedon of Martin Luther King father and son. That began the Vision and Justice Project.

Alison Stewart: I would love it if you'd read the first paragraph of your essay about that photo.

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: With pleasure. Here we go. "A man seems to hover. He gazes intensely straight through the camera right at us. His body is hidden entirely by a seated, suited older man and a young boy in a plaid blazer wearing a bow tie. Together, they cohere into an eternal architecture, the apex position held by one in their prime. An elder is seated as if a foundation, the young boy, chin raised that attention seated closest to the camera, a reminder of our duty to the future.

The hovering man we know is Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The elder figure is his father. The young boy is his son, Martin Luther King III. The photographer we know is Richard Avedon. The portrait is an emblem of an unflinching craftsman who could transform icons into parables, individuals into myth. To view Avedon's work is to dwell on the stunning feet and cost of the human lineage. Avedon's composition places the King family emphatically in our sights, the photograph, diagrams, and exhortation.

The King family is presented not only as theirs but also insistently in line with our own." I'll end there.

Alison Stewart: Professor, why was that the right image for the work you were doing?

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: As I write in the piece, I sat just immobilized by that portrait one night in 2015 as I was constructing the issue. I had been trying to find an image that just emblematized the mission of what would become the Vision and Justice project. One of the courses I teach at Harvard was launching at the time with that same title. I realized that in that image, we were able to understand the work of the project through the force of Avedon's composition.

That right to be recognized justly in American democracy has required the work of culture and visual representation and that insistent gaze that you see in this photograph. There are many others you could have chosen. The contact sheet also published in the book showed it, seemed to be, as I've read it, Avedon's desire for us to see how connected we are, not just with these three individuals, but with what they represent and with the work of culture to underscore its work in the world.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing Avedon 1-- Oh, I'm sorry, continue.

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: No, no. That's why the image was so gripping and why it's an honor to have been invited to write about it. Thank you to James and everyone at the foundation.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing Avedon 100. It's at the Gagosian Gallery. My guest are James Martin, executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation and Professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis. James to your point, there were definitely themes in the show as you go through, and it's organized so that we do get that breadth of his work as you walk through. I was really moved by some of the more personal photographs in the exhibition.

There's a terrific photo of Avedon with a young James Baldwin, and they're staring into a mirror. It's one of those pictures that we all took as kids in a mirror. For folks who don't know, they were high school colleagues and they ran a school publication together, how did their friendship evolve into a working relationship as well?

James Martin: Thanks for that question. It's really one of the more fascinating parts of the archive. Looking in to the documents and the negatives in the archives, you really sort of get a glimpse of how these relationships came together. Avedon kept all of his negatives. We have about 500,000 that are in the archive. If you look really closely at the beginning, the forties, which are chaotically numbered, you start to see trips that Avedon took back to the Baldwin house, he was there to photograph Jimmy to take a portrait of him for some unknown reason.

We see throughout the negative documentation that he makes his portrait in the studios of Junior Bazaar at the time, Harper's Bazaar Junior and the photographs that are of Avedon at Jimmy's house show him showing these finished proofs to his mother. There's no direct correspondence that we have back from there, but you can really start to piece together these relationships. Then a few years later, about 20 years later, they were out, Jimmy was being photographed for Vogue. Avedon took his photograph, and that's where the project starts. It eventually becomes the book, Nothing Personal.

Alison Stewart: Professor, the exhibit really highlights Avedon's commitment to civil rights. Where in the exhibit do you think we see this? What's an example of some of that strong imagery that was really important in telegraphing what the Civil Rights movement was about? Also through his lens, both literally and figuratively, I guess.

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: There are many examples. I think you might expect that my answer would be to look to say photographs that he took of leaders in SNCC, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, for example. He was committed to helping teach those within the organization, use photography as a means for the beautiful struggle, and to advance it.

I actually think that there is, and it's to James' earlier point, a way in which we can see through even the fashion photographs. Say Daniele Luna, his understanding of the need to bring an ethos of racial equity into other arenas that aren't necessarily seen as overtly political, like the fashion arena. He was, as I understand it from the archives, barred from incorporating Black models into his guest edited Harper's Bazaar shoot, and he chose Daniele Luna to be his featured model and was barred from ever doing so again.

His understanding of the need to push these boundaries became an ethos through which he would really push past prejudices throughout many of his photographs in all domains of life.

Alison Stewart: There's also photos chosen by the family, James. It was so interesting to see from his son and his grandchildren, Matthew, Michael, William and you mentioned, Laura earlier, and I thought it was so interesting because-

James Martin: Caroline Avedon too.

Alison Stewart: -and Caroline, thank you. John picked his mom, which I think was lovely, but I thought it was interesting the kids picked more iconic images. I'm so curious about the conversations with the family about the images because they knew him best.

James Martin: Of course. For the family, it's hard because they're also very close to each of these images. There's also a re-examination that needs to take place. The image of Chet Baker is fantastic, but it's not as well known as say, your Dovima with elephants, your [unintelligible 00:13:51] the Marilyn Monroe images. This allows the family to take a closer examination of both very personal images, like as you mentioned, the photograph of Evelyn, and also wider known, but images that needed closer examination. I think that's where those choices came together.

Alison Stewart: James, where do we see that he was a New Yorker in this show?

James Martin: Oh, all over, all over this book. His studio is on the Upper East Side. He moved it several times, but it stayed within that 20 block radius. It's really bringing in everybody with the few exceptions. Of course, he did travel and he traveled out west, and he traveled extensively for a lot of these major photographs. This exhibition is truly a homecoming for all of these photographs. You can really see the New Yorkness in all of these photographs.

Alison Stewart: Avedon at 100 is at the Gagosian Gallery at 522 West 21st Street through June 24th. My guests have been Professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis and James Martin, executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation. Thank you so much for spending time with us today.

James Martin: Thank you, Alison.

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis: Thank you, Alison.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.