Revisiting Steven Spielberg's Biggest Year, 1993

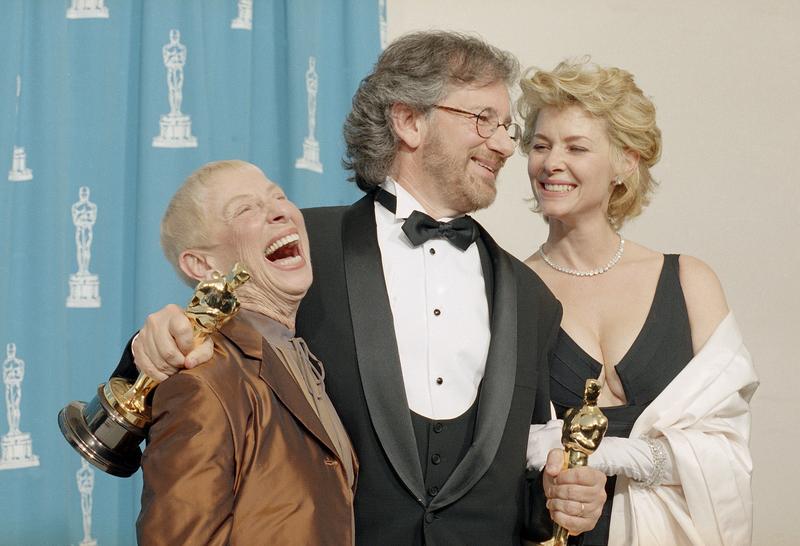

( AP Photo/Lois Bernstein )

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. This is a big year for Steven Spielberg. Not only is the film about his life, The Fabelmans up for six Oscars, including Best picture. This year was the 30th anniversary of two of Spielberg's career-defining films, Jurassic Park and Schindler's List, a dinosaur action adventure, and the true story behind Oskar Schindler and the Holocaust could not be more different, and that's what's remarkable. They came after a five-year dry spell after a whole lot of success in the '70s and early '80s.

Jurassic Park and Schindler's List also cleaned up the box office and in award categories with Jurassic Park grossing almost $1 billion and Schindler's List and Jurassic Park receiving a combined 10 Oscars. We're joined now by movie critic for Vulture in New York Magazine, Bilge Ebiri, to talk about what was going on in 1993 and walk through some of Spielberg's most impressive works. He wrote a list reviewing all of Spielberg's films. Ranked Worst to Best. Bilge, welcome back.

Bilge: Hi there. It's good to be here.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we want you to be a part of this. What is your favorite Stephen Spielberg film? Why? Let us know. Do you have a story perhaps about seeing Jurassic Park or Schindler's List in theaters, or maybe another film you saw of his, maybe you have a personal connection to one of his films. Give us a call. Our phone lines are open. 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692 to share or tell us, or you can reach out on social media @AllOfItWNYC, that's both Twitter and Instagram. Bilge, when you think about a Steven Spielberg film, what makes a movie a Spielberg movie?

Bilge: Wow, that's a big question. I grew up with Steven Spielberg movies. I'm 49 now, so I was just the right age to be seeing Raiders of the Lost Ark and ET in theater. Back then, the idea of a Spielberg film was it was very family-friendly. It had great sci-fi-ish, actiony set pieces. Very often it featured a child or a childlike character at their center. Over the years, they've changed quite a bit. In fact, they start to change right around this time when he makes Jurassic Park and Schindler's List. As he grows up and as he becomes more of an adult, obviously he was an adult when he was making movies, but he becomes a father.

He has a big family, and he starts to make films that feel less like they're from the point of view of a child and more like they're from the point of view of a grownup, a parent very often.

Alison Stewart: That's how it changes. What are some of the elements of a Spielberg film that some remain the same that you know you're going to find in a Steven Spielberg film?

Bilge: He's a very precise technician. He really understands the craft of filmmaking. He knows exactly how to move the camera. He knows how to close in on certain details, not necessarily because they're important, but because he needs to. He's a magician, so he diverts your attention to something in the frame, but then something else happens that's actually more important then he uses the element of surprise. One thing I've always said, I actually think he's a horror filmmaker at heart. Some of the very early films he made right at the start of his career were in the horror genre. He hasn't really returned to that genre, but all his films have these elements in them.

If you think about a movie like Raiders of the Lost Ark, yes, it's a wonderful rip-roaring fun adventure for the whole family, but it is terrifying. Eight-year-old me was terrified of that movie and Jaws obviously, but he's never stopped doing that. If you look even a movie like The Post, which is a historical drama about the Pentagon Papers, it's shot like a thriller. The way he moves the camera, the way he uses light and shadow, it's shot like a thriller. The plot could just be slightly different and it could actually be a thriller.

Alison Stewart: Calls are coming in. Let's go to line two, talking to Artie from Queens'. Hi, Artie. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Artie: Guys, I love Steven's movies. You left out Duel, not to mention the fact he is the only director I can think of who worked with people from Joan Crawford all the way up through Kevin Costner and to the generation now that's making movies, but my favorite Steven Spielberg film is probably Private Ryan. My father was still alive when it came out, and I remember him and the whole cast on The View. [chuckles]

They had so many questions to ask him from all his different movies that his head was just spinning like a bobble. [laughter] Barbara would ask something and Joy, and then Whoopie, [laughs] but yes, I guess probably Ryan is my favorite because it makes me think of my father and his generation.

Alison Stewart: Artie, thank you so much for calling in. Let's talk to Alex from Brooklyn. Hey, Alex, thanks for calling All Of It. You're on the air.

Alex: Hey, you're welcome. My most vivid movie theater memory and still the most terrified I've ever been while watching a film was eight years old. My father took me to see Jurassic Park at the Ziegfeld Theatre, rest in peace, and we were in the third row from the front. I white-knuckled it the entire time. My entire view was dinosaurs in front of me, and it was just a thrilling, terrifying, and vivid experience.

Alison Stewart: Alex, thank you so much for calling in. That's a lovely segue to our discussion of Jurassic Park. It was an early example of CGI, which created those huge scenes, these very scary scenes. What was the initial response to this new technology, Bilge?

Bilge: It was a huge, huge hit. The initial response was very positive and predicts liked it as well. Spielberg had always been at the forefront of technology. Special effects and things like that were obviously so important in films like Raiders of the Lost Ark and Close Encounters and Jaws and ET, obviously. CGI, at that point, we'd seen some of it in a movie like Terminator II and The Abyss and things like that. We had seen that, but we knew that Spielberg was going to do something special with it, and he absolutely did. What is interesting though, is if you watch Jurassic Park now and they re-released it a few years ago in 3D.

I remember seeing it in 3D when it came back in theaters, and I actually was surprised by how janky the special effects looked. They didn't look as perfect as they did, but that actually almost enhanced the experience. When I saw it in 1993, the effects were incredible. When I saw it again in 2013, the effects were not as incredible, but then it started to feel more like one of those old-timey creature features that the movie itself was referencing. It became a wonderful historical artifact that still works really well. Like I said, he's a horror filmmaker at heart, and Jurassic Park is if it ends differently, it's a horror movie.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Let's take a listen to a clip. The welcome to Jurassic Park clip, in which the creator of the park, John Hammond, is welcoming two scientists played by Laura Dern and Sam Neill, who are overwhelmed by what they're seeing that Neill's character even feels faint. This is from Jurassic Park.

[dinosaur coos]

Dr. Alan Grant: How fast are they?

Dr. John Hammond: Well, we clocked the T-Rex to 32 miles an hour.

Dr. Ellie Sattler: T-Rex?

Dr. John Hammond: Yes.

Dr. Ellie Sattler: You said you've got a T-Rex.

Dr. John Hammond: Yes.

Dr. Alan Grant: Say again.

Dr. John Hammond: We have a T-Rex.

Dr. Ellie Sattler: Put your head between your knees.

Dr. John Hammond: Dr. Grant, my dear Dr. Sattler, welcome to Jurassic Park.

[dinosaur coos]

Alison Stewart: Jurassic Park turns 30 this year. My guest is Bilge Ebiri. We are talking about the anniversary of Jurassic Park and Schindler's List 30 years ago, released as well as the career of Steven Spielberg. Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Maybe you want to share your favorite Steven Spielberg movie, or maybe you want to share something about seeing Jurassic Park or Schindler's List in theaters, what those movies meant to you. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

Bilge, I want to know a little bit about what the movie industry was looking like in 1993. We can have some context for both Jurassic Park and Schindler's List. If we transported back to 1993, what was the vibe? What was the ethos of Hollywood at that time?

Bilge: Technology has created almost a new genre of action movies, sci-fi movies, and things like that. It's interesting for Spielberg, he actually went through a period in the late '80s, early '90s when his films weren't quite as successful. They were still successful. He was still Steven Spielberg, but that's when he makes Hook, which is a movie I personally love that predicts were pretty critical of it. There was actually a question of can Steven Spielberg get back to being the King of the Box Office that he had been in the '80s and late '70s. Jurassic Park obviously solved that, to answer that question.

There was also a question about Schindler's List because he was also in the process of becoming a more serious director or "serious director." He wanted to tackle more important subjects. He wanted to tackle more dramatic subjects. As I said, he himself was kind of growing up, if you will. He had done films like Empire of the Sun, again, a movie I personally love, but which was not as well received as I think he had hoped. There was this question, can Steven Spielberg make the "Oscar movie" because that's how we thought of them back then. Oscar movie is a period piece. It's about an important subject. Schindler's List absolutely cleans up not just at the Oscars, but all the Critics Awards and things like that.

It's a total award season juggernaut as well as a big hit. Both of those questions are answered and actually, it's only a couple years later that Spielberg creates his own studio, essentially, goes into partnership with Jeffrey Katzenberg and creates DreamWorks.

Alison Stewart: I want to ask about Schindler's List, his expansion into capital "D" drama. You talked about how it cleaned up at the Oscars. For people who don't remember, Oskar Schindler was a German Catholic industrialist and member of the Nazi Party, and during the Holocaust, he bribed officials into letting him retain Jewish workers. He's credited with saving 1,200 people who otherwise would have been sent to death camps. As you said, he wanted to go into dramatic film and to more grown up films. How did this film after critical success, how did it change the trajectory of his career?

Bilge: It changed it in a couple of days. First of all, it was a very personal project for him. I've talked about it as a big Oscar prestige period, but it was a very personal project for him. We see in The Fabelmans, which is a semi-autobiographical film, we see how the young Steven Spielberg, Sammy Fabelman, in the movie has to deal with antisemitism and things like that as a youth. That was very important for him. At the time, he actually said something along the lines of, "I can't imagine myself making another action movie with Nazis as the bad guys."

There was actually the sense that he was going to move away from the "kiddie pictures." He never did, actually. He comes back and he makes a Jurassic Park sequel, but he does, I think, start to make films that speak to him personally much more. I think the films become much more personal. We talk about his one-two punch of 1993. He has a number of years that constitute one-two punches. 1997 he makes The Lost World and he makes Amistad, which is again, a very personal movie for him. In 2002, he makes Minority Report and he makes Catch Me If You Can.

Again, one is a big sci-fi blockbuster with Tom Cruise, the other is a period drama with Tom Hanks and Leonardo DiCaprio. Both are big hits. Both are amazing films. I actually think both are very personal, and one is much more personal for him than the other.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Bilge Ebiri, movie critic at Vulture and New York Magazine. We're talking about Steven Spielberg's big year of 1993, and we're going to continue to expand the conversation, take more of your calls about your favorite Spielberg films after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Bilge Ebiri, movie critic at Vulture and New York Magazine. We're talking about the career of Steven Spielberg on this 30th anniversary of his films, Jurassic Park and Schindler's List. Let's talk to Dan calling in from Brooklyn. Hi, Dan. Thanks for calling in.

Dan: Hi. Schindler's List was unique in that instead of presenting this black and white picture of the Holocaust where you either were on one side or the other, and that's it, you either hate it or loved it and so on, in Schindler's List there was this [unintelligible 00:14:13] humanity that ran through both sides, and had a tremendous impact, especially in older people who lived through the World War II and subsequent wars. It really raises this issue that the bad is not always totally in the bad and the good is not always totally in the good. As for Jurassic Park, very frankly, the lessons you teach college students in biology and especially in evolution, they just can't see it, they can't imagine it.

You're showing them a bunch of bones and so on, but that film, it just put them right into that period. The amount of interest we saw in paleontology after that was just unbelievable. I have to say that sometimes baloney movies like this can really generate a quantum jump in student interest in paleontology and things like this. It may well apply to other science like space science and so forth. I just think these two movies had tremendous contribution that he made, and he took a lot of chances making it because people like to be dumb as a rule.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Dan, thank you so much for calling in. I'm not going to say all people want to be dumb. Let's talk to Angela from Brooklyn. Hi, Angela.

Angela: Hi. How are you?

Alison Stewart: Great. You're on the air.

Angela: My favorite Spielberg movie is Duel. My story that I want to tell was going to see Jurassic Park. I don't like scary movies. The scene with the kids in the kitchen, I was really getting scared and my boyfriend leaned over to me and whispered, "It's okay, honey. It's not Stephen King. The kids don't die in Spielberg movies." I could relax then and watch it without being too freaked out about it.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for calling in Angela. Really appreciate it. Someone, Steve said, "My favorite Spielberg movie is definitely E.T. That's the movie that kicked off my fascination with alien life forms and my love for Reese's Pieces candy." Bilge, this is so interesting, people talking about the cultural impact of Spielberg films. The one caller who talked about interest in science, this person talking about a fascination with alien and life form. I hadn't really put that together.

Bilge: Because he is a big filmmaker who does big projects, there's a lot of attention on these films, but he does give these subjects a real reckoning and a real investigation. The earlier caller, I believe his name was Artie, who talked about Saving Private Ryan-- when Saving Private Ryan comes out, it really inaugurate the whole period of discussion of the Greatest Generation and World War II and things like that, and like they said, very much so the case with Schindler's List. Up until that point, there had not been a lot of movies about the Holocaust.

After Schindler's List, we get a lot of movies and documentaries and things like that, some of which Spielberg himself produces. All of these movies, especially the big ones, really have social and cultural long tails beyond just cinematic ones.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Peter calling in from Jersey City. Hi, Peter. Thank you so much for calling All Of It.

Peter: Hi. I just wanted to remention the contribution of John Williams to most of Spielberg films, and just the way that he responds to the tone that the Raiders Lost Ark music is so different from The Schindler's List score. There's, of course, the Jaws theme. There's the last 20 minutes of E.T. that begins with the bicycle chase and ends with the spaceship lifting off, which is gorgeous and operatic and very dominant in the scene. There's very little dialogue in that final scene. It's mostly about the music and the actors' faces.

Alison Stewart: Peter, thank you for calling in. Peter made me think of something, that Spielberg has regular collaborators. He has a cinematographer, he often works with. Is it Janusz Kamiński? Am I saying it right?

Bilge: Yes, Janusz Kamiński in the more recent ones starting with Schindler's List or right around that time, I think.

Alison Stewart: John Williams is a composer that he works with as well. That is part of the job of being a filmmaker is picking your collaborators.

Bilge: Absolutely. We talk about directors as auteurs. Very often there's this image of a lone figure who's making all the decisions. The greatest filmmakers are often working with other people, and they're often working with the same people over and over again. Spielberg also has used the same editor, Michael Kahn, on a lot of films. In recent years, he's worked with Tony Kushner, the playwright on the screenplays to the films. These people are crucially important to the movies that he's making. He is someone who is obviously known as someone with a billion ideas of his own and the visionary, but he's also known as someone who collaborates very closely with people.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Edson calling in from Manhattan. Hi, Edson. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Edson: Hey, Alison. Thanks for taking my call. I'm from Brazil, born and raised over there. In one movie that stick with me was The Color Purple because it was nominated, I believe, to 10 or 11 Oscars, but didn't get any. Also, I would like to ask your guest why you think Steven Spielberg decided to make the movie with Whoopi Goldberg-

Alison Stewart: Whoopi Goldberg, yes.

Edson: -Danny Glover, and Oprah Winfrey. I just want to add something. When I was over there in Brazil, I didn't realize about redlining. When I see today movies like E.T. and I see the suburbs. They show the suburbs and you don't see black family at all in a lot of those movies. When I was over there, I didn't realize but living over here now in New York, I see, whoa, those directors, they reinforce the stereotype about the suburbans and the lack of black families, African American families living in the suburbs.

Alison Stewart: No, 100%. I'm going to dive in because that's a conversation we could have about what we export to the rest of the world through our films. I think it's a good segment, actually. Let's get back to the specifics of The Color Purple, Bilge.

Bilge: Well, The Color Purple, as, I think the guy's name was Edison, he noted, The Color Purple was nominated for all those Oscars and didn't win. It was obviously a very acclaimed film. That was actually during that period when people thought Spielberg was never quite going to be accepted as a serious filmmaker. Obviously, the film was a huge hit. It's also Whoopi Goldberg's acting debut. It's Oprah Winfrey's acting debut. I think it's a great film. I think time has treated it a lot better than people thought it would.

You're absolutely right, those early classic Spielberg films like E.T., something like Raiders of the Lost Ark, they're not necessarily particularly enlightened in terms of depictions of race and depictions of other cultures and things like that. As he grows though, he does begin to focus on these issues. He himself has African American children. It's something that has become more and more of a concern for him with those films. I think that also shows how his films have become, in some ways, more socially conscious.

Alison Stewart: One film that people should check out, which is not a conventional choice. What is it, Bilge?

Bilge: Oh, God, what a great question. A.I. is one of those films that at the time that it came out, it received mixed critical response. I, myself, was a little ambivalent about it, but over the years, it just feels more and more powerful, more and more personal to him. It's all about an artificially intelligent child being brought into this biological family. You can tell his issues as a parent and his concerns as a parent and a father are really working themselves out in that film.

Alison Stewart: Thanks to everybody who called to recognize Steven Spielberg's work and to Bilge Ebiri from Vulture Magazine. Thanks, Bilge.

Bilge: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: That is All Of It for this week. [music] All Of It is produced by Andrea Duncan-Mao, Kate Hinds, Jordan Lauf, Simon Close, Zach Gottehrer-Cohen, L. Malik Anderson, and Luke Green. Our intern is Katherine St. Martin. Megan Ryan is the head of live radio. Our engineers are Juliana Fonda, Jason Isaac, and Bill O'Neill. Lucius Jackson does our music. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening. I'll meet you back here next time.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.