A Retrospective of Artist Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

( © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Photograph )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. In the past few years, there have many firsts for artist Jaune Quick-To-See Smith. In 2020, she became the first Indigenous artist to have her work acquired by the National Gallery. This year at 83 years old, Smith will also be the first native artist who curate an exhibition at the National Gallery. Today, a major retrospective of Smith's work opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The first time the museum has ever dedicated a retrospective to an Indigenous artist. First are great, but they're always a little tricky for people of color. Sure, it's great, but there's always the, what took you so long of it all.

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith is a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation. For more than five decades, she has made art, painting, sculptures, and drawings reckoning with the land that doesn't recognize its original inhabitants. Vulture says of the artist, "Smith is one of America's greatest living artists, and failing to acknowledge that would be madness."

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map is on view at the Whitney until August 13th. With me now in studio is the show's lead curator, Laura Phipps. Laura, thank you for coming to the studio.

Laura Phipps: Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: You visited Smith in New Mexico and spoke with her many times through the process of organizing this show. When you visited her, what struck you most about her practice?

Laura Phipps: Oh, sure. The very first time that I even reached out to Smith about being in her studio, I said, "Can I come visit you?" She said, "Sure, but you're going to have to make time to go and see this artist, and this artist, too" I said, "Okay, this is how this is going to work." We are building a relationship together and we're building a relationships out. That has definitely been a mainstay of our work together.

Alison Stewart: What was it about these other artists that she wanted to see? What was the point she was trying to impress upon you?

Laura Phipps: Sure. They were also contemporary Indigenous artists, and a huge part of Smith's practice has been bringing others along with her, using whatever platform she has to introduce others to contemporaries that she really believes in. One of the artists happened to be her son, Neal Ambrose-Smith, who's also an excellent artist, and then other younger artists that she is just excited to support, wants to see them succeed.

Alison Stewart: I want to make sure people understand when I'm saying her name. It's spelled J-A-U-N-E, Quick, T-O S-E-E Smith, so it's Jaune Quick-To-See Smith.

Laura Phipps: Correct.

Alison Stewart: She's born 1940 in St. Ignition's Mission on Flathead Reservation in Montana. What clues are there from her early childhood that hint that she would become an artist?

Laura Phipps: Sure. She says that she knew she wanted to be an artist from a really early age. I think that part of that came with her childhood was quite itinerant. She was raised by her father, and they moved around quite often between Montana and the Pacific Northwest, but art and making was a constant. It was a form of communication, something she and her father shared, and I think the physicality of it was always really important.

When we see in her work now this mark-making related to her study of petroglyphs, or we see even some of the colors and materials she uses are really references to the places she was raised. Not only the land, but also her father worked with horses, and a lot of that imagery comes back through in her work.

Alison Stewart: What kept her going in the face of something almost worse than rejection, discouragement?

Laura Phipps: Sure. She's incredibly determined [laughs], and I think that in some ways, the discouragement was encouragement. Being told that you can't do something I think in some ways fueled her interest in figuring out how to actually do it. That is true not only of her education, true of the way that she has found a voice as an organizer and a curator, and then also through the work that she's making just pushing against stereotypes.

Alison Stewart: This retrospective is huge. How much the square footage? Can you tell us the square footage-

Laura Phipps: Oh, gosh.

Alison Stewart: -of it, and if you can guesstimate how many pieces?

Laura Phipps: Sure. Yes, numbers not my forte, but it's around 12,000 square feet. It's on the fifth floor, on the third floor, and then some surprises throughout the building. You encounter her work in unexpected places. There are over 130 objects in the show--prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures, and ephemera to really try and tell that full story of her practice.

Alison Stewart: We are talking about Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map. It opens today at the Whitney Museum. It'll be on view till August 13th. I'm speaking with Whitney's assistant curator and lead curator on this particular show, Laura Phipps. Let's talk about a few things. I want to talk about the first few things you see when you get off on the fifth floor elevator. Describe the first painting we see, the first piece we see, and why that's the first piece.

Laura Phipps: Sure. The first piece right off the elevator is a three-panel painting called "Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights". It's a painting that Smith did in 2015, one of the more recent paintings in the show, and it's really big. [laughs] It's over, I think, yes, 100 inches long, something like that.

The canoe, and the trade canoe in particular, is a motif that is repeated throughout Smith's work often in this large scale. She uses it as a container for her ideas, for imagery, for her concerns or dreams, things that are on her mind. The concept of the trade canoe as something that carries things along has a history with her own ancestors and history of trade. It also, she's creating its new history, and we use that concept really throughout the show. The trade canoe reoccurs in a way carries these ideas along through the show. That work in particular, the "Forty Days and Forty Nights" might sound familiar as a biblical reference. Since is really thinking about some of the shared stories that we have across culture, the idea of shared creation stories, stories of flooding, and she fills the canoe with animals and objects, things that we would want to save, things that are culturally important.

Alison Stewart: On the other end of the spectrum of things that will be filling a canoe, there's a sculpture that hangs from the ceiling that is red and it's a canoe, and it casts a beautiful shadow and it's full of things, sculptures. You realize when you get close, it's like old soda bottles and the styrofoam containers and all sorts of refuse and hygiene--

Laura Phipps: Epidermic needles, single use plastic, yes.

Alison Stewart: What story is that canoe sculpture telling?

Laura Phipps: A number of Smith's works really are looking at the way that traditional foodways and traditional medicines have been decimated by colonialism, by policies put in forth by the US government over centuries. That work in particular, really thinking about how taking food and medicine from the land has been discouraged, and instead replaced with fast food, with western medicine. There are also wooden crosses in there, and Smith made that piece in collaboration with her son, Neal Ambrose-Smith. They talk about how this is all the stuff they want to give back. Canoes were for trade, trade is an exchange. What if you don't want what you were given.

Alison Stewart: After you step off on the fifth floor, and you see that large trade canoe painting, if you go to the left, you're greeted by a sculpture. It looks like a female form wearing traditional native clothing, sitting in a chair. There's a flag draped across a lap. The hands are really interesting because they're feathers. The face is a face in a picture frame and the figure's holding a book God Is Red. It's a 50-year-old text about native religion. What is the name and origin of this piece or the figure that greets us?

Laura Phipps: Sure. The work is called Indian Madonna Enthroned, and it's from 1974. It's one of two works from that year, the earliest in the show. Oh, it was such an excellent discovery. [laughs] I'd seen it in photographs in Smith's home, but until I visited her storage facility actually in Corrales, New Mexico and saw it up at the top of a shelf sitting on its back, I'm like, "What is that?" We're so thrilled that it could come back down. [laughs]

Smith finished her undergrad degree in Massachusetts at Framingham, and was at the time studying art history and art education and spent a lot of time learning about the Italian Renaissance, focusing on Italian Madonna's.

That reference and then also seeing the work in New York museums of contemporaries like Edward Kienholz and Marisol, and their treatment of the figure, and use of their own symbols really encouraged her to go back to her studio and make her own Madonna, something that reflected her own understanding of her identity and culture. Yes, she's infusing this idea of a Renaissance Madonna with these contemporary Indigenous symbols, the corn in the woman's heart, the feathers, and buck skin. Really, thinking about the connection between humans, animals, nature, that's so important to Smith and her worldview.

Alison Stewart: I'm having an image of you going into her storage facility. What was that like?

Laura Phipps: Everything was framed and beautifully maintained, and then there are things that you can pull out and see. This was the real surprise there. When you see the piece in the gallery sitting up on a pedestal in this new context, just imagine it sitting at the top of a shelf, sitting on her back. She's had a long life, Indian Madonna.

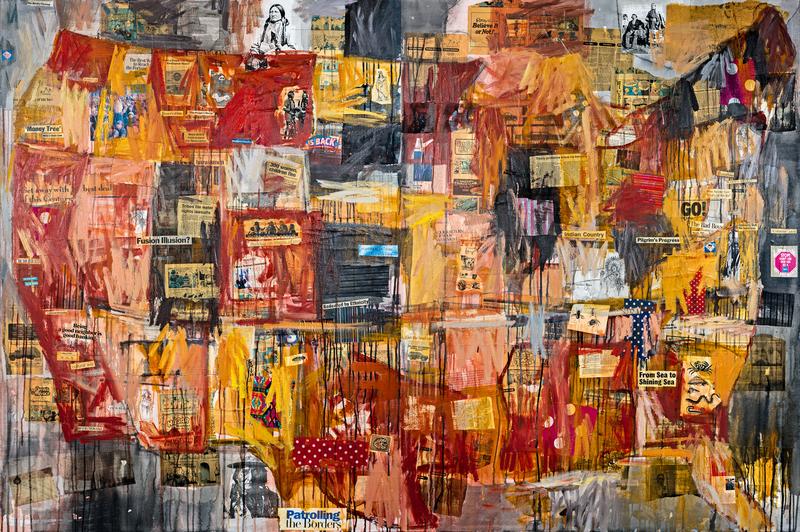

Alison Stewart: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map is at the Whitney right now. I wanted to mention that American flag, because it's in the lap of the Madonna piece. We see the American flag again and again in the show. There's a piece called McFlag, which is oil, newspaper, and paper on canvas. It's a flag, and there's lots of newspaper pieces collage in. On the ends, there are two round black speakers that look like Mickey Mouse ears at the top. Then there's an electrical cord, which looks like a tail at the end. The wall text describes it as a piece that is anti-capitalist. How so? What do we know about Quick-to-See Smith relationship with the flag?

Laura Phipps: Sure. In some ways, the flag is actually related to her use of the trade canoe, this idea of motifs that can be recognizable. The flag, of course, conjures up all of these other feelings, and in some ways, has become ubiquitous in art history as something that artists use and manipulate, maybe starting with Jasper Johns, who's an artist that Smith talks a lot about having this interesting relationship with his work. The flag, we see it, as you said, in Indian Madonna enthroned and really sets this idea of a relationship with America and what that means.

When Smith is using the flag, it's a way for her to use a form that's recognizable and rethink it, to inject her own, meaning, in history and that particular work, McFlag, with the Mickey Mouse ears and the tail includes a lot of language really around multinational corporations, their reach into our lives. It's not only this reference to Mickey Mouse and therefore Disney, but also the language in the painting says, "McFlag, big, bigger, best." It's this idea of this advertising language as well. All these things that we recognize. Then as we read more, look more, we maybe rethink our relationships.

Alison Stewart: Is she someone who considers herself an activist?

Laura Phipps: Oh, yes, an activist and an advocate, really. It's very antically tied up in her work.

Alison Stewart: That's not to say she's not a humorless person. There's quite a bit of satire in her work. What's a piece you think really shows her sense of humor, her sense of satire?

Laura Phipps: Sure. One of the first works that you see also in the show is another trade canoe that is related to-- It was from 1996. It was a time when the Tongass rainforest in Alaska was being threatened, I believe, by expanding logging, expanding drilling. There's some great text, I think, around the protest to save this rainforest, but also counter-protest by the logging industry and individuals who made their living there. There's a great headline that says, "Save endangered loggers."

You come into this show with maybe you already have a little bit of a sense of what this artist is all about. You see this work that also has illustrations of caribou, and these beautiful blues and greens, and you think, "Okay, I get it. We're saving the environment here." Then you read this large text that says, "Protect endangered loggers." I think that tongue-in-cheek use of language that she was finding, but incorporating it and really flipping it around.

Alison Stewart: I particularly like the faux paper dolls that she makes. Aside from embracing the historical nods to things like Renaissance painting, she's very invested in pop art as well.

Laura Phipps: Absolutely. I think the flag is a great example of that and the paper dolls as well. She's taking something that, again, is recognizable. Maybe people have a memory of playing with paper dolls. She's naming them Barbie and Ken. Then the context that they're in is a Salish family who have been really affected by colonization by the work of missions in Montana, and their opportunities and their cultural connection have been lost. You see this play out in the ensembles that she's drawing alongside them.

Alison Stewart: The name of the exhibition is Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map. It opens today at the Whitney Museum. It's on view until August 13th. A lot of hip folks are Whitney members. Remind people when they can go see it for pay-what-you-wish.

Laura Phipps: Sure. Friday evenings are pay-what-you-wish. I just also want to plug that this Saturday, April 2nd, which is Earth Day, is an opportunity to come to the museum free of admission. It's also a great opportunity to see both Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, the new Josh Klein project for a New American Century that opens, and catch no existe before it closes.

Alison Stewart: We had two of the artists on the show. That's a terrific show as well.

Laura Phipps: That's great.

Alison Stewart: Laura Phipps, thank you so much for joining us.

Laura Phipps: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: That's All Of It for today. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening, and I appreciate you. I'll meet you back here tomorrow.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.