A Prolific Art Thief Who Kept What He Stole

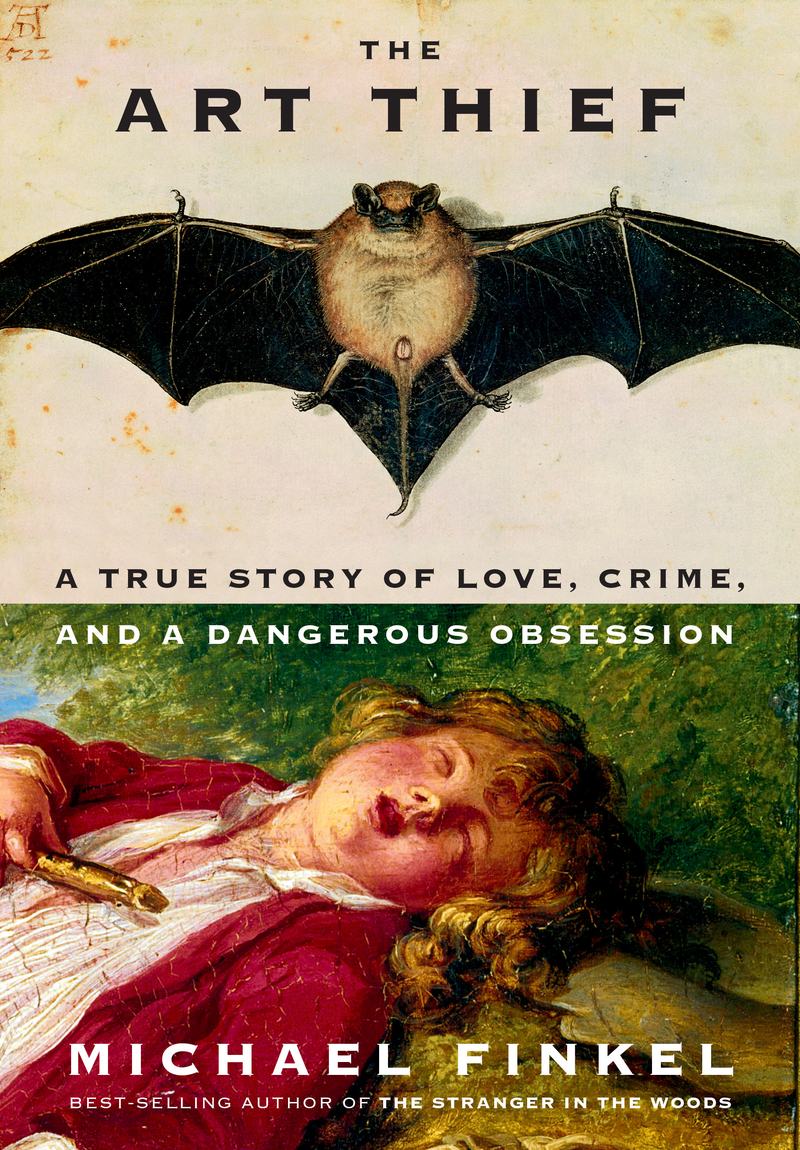

( Courtesy of Knopf )

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Arun Venugopal: You're listening to All Of It. I'm Arun Venugopal sitting in for Alison Stewart. Believe it or not, one of the most prolific art thieves in history didn't steal for money. Instead, he hoarded around $2 billion worth of stolen art in two locked rooms in his mom's house, rooms that he shared with his girlfriend and accomplice. Even after he was caught, the French thief, Stéphane Breitwieser insisted he just wanted to admire all this beauty in his own space and intended to have the art returned at some point. Unlike most art thieves, however, Breitwieser and his girlfriend Anne-Catherine did not spend months planning their heist, instead, the thefts were spontaneous, often conducted in broad daylight with tourists and security guards quite close by. Breitwieser stole often, sometimes almost once a week.

He took Renaissance oil paintings, he took goblets, statues, antique muskets, even took one gigantic tapestry. Took years for the authorities across Europe to figure out that they had a unique and prolific thief on their hands. Breitwieser was eventually caught, but not before tragic consequences befell the art he claimed to love so much. This wild story is captured in the New York Times bestselling book from author Michael Finkel, it's titled The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession. Michael Finkel joins me now to discuss. Hi, Michael.

Michael Finkel: Hi. Happy to be here.

Arun Venugopal: You actually interviewed Breitwieser for this book. How did you get him to agree to speak with you?

Michael Finkel: If you're going to describe my working methods in one word or less, I would say they're inefficient. I worked on this book for 11 years. I want to stress that this is a true story, a 100% true, not based on a true story or 99% true. I had read a tiny bit about Breitwieser, and it was journalistic catnip, not just the insane quantity of thefts, more than 200 museums and churches he stole from, I mean, the second most prolific art thief stole from '90s. There's really no second place. I liked the way he stole during the day without violence, sometimes with guards in the room, but what really pushed this into obsession for me was the fact that he didn't do this for money. He seemed to steal for love.

I exchanged handwritten letters with Breitwieser for four years before he agreed to meet me for lunch, and I wasn't even allowed to bring a notebook to that lunch. After that lunch, he finally agreed to sit for some interviews. We spent more than 40 hours together, including possibly the most bizarre experience of my journalistic life, which was to visit a museum with the world's greatest art thief.

Arun Venugopal: You start the book with this really gripping account of a theft. Tell us a little more about this particular incident and why you chose to open the book there.

Michael Finkel: Breitwieser stole 300 works of art in his more than 10 year career, and one of his favorite things was this ivory sculpture of Adam and Eve from the early 1700s. Breitwieser's stealing style was both simple and highly risky, to steal this 10-inch high ivory sculpture, he unscrewed a couple of screws that were holding this piece inside of a plexiglass display box. Now, he would screw it like one or two turns at a time between tourist visits and guard entrances. His girlfriend, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus served as his lookout.

Finally, after about 20 minutes of work, a couple of seconds at a time, he was able to lift the display case top off, stick the ivory sculpture at the small of his back, put his long coat over it, and for those of you considering stealing art, don't run out of your museum, walk out of your museum.

Arun Venugopal: Be cool.

Michael Finkel: It sounds about as simple as that, but it was also, of course, extraordinarily risky. He put this particular piece on his nightstand in his bedroom where he displayed all of his works, and he said it was one of the first things he saw every morning for years as he opened his eyes.

Arun Venugopal: Paint the scene for us, this home of his, where he has all of his loot. Where is he living? Alsace. Does he live in Alsace? Is that the--

Michael Finkel: Yes, he's in Alsace region of France. This where Germany, Switzerland, and France all meet. He's Alsatian, but if you haven't heard of the French city of Mulhouse, that's because it's probably the least touristy town in all of France. It's where they make automobiles and manufacture chemicals. He lived in this most nondescript house. If you asked a two-year-old to draw a house, it would probably do a square with a drawing along top, and that's what his house looked like. It's his mother's house.

Breitweiser was a full-time art thief, which is another way of saying he was an unemployed freeloader. He lived with his girlfriend in these annex rooms of his mother's tiny house. You enter this house, his mother lived on the ground floor, and you go up this very narrow set of wooden stairs and you open this door. I'm telling you, if I could have seen this in real life, I would have paid all sorts of money. I saw videos of it.

You open this door and in the middle of this attic chamber with low ceilings and slanted roof beams, was this amazing four-poster bed, and surrounding the four-poster bed was an estimated $2 billion worth of stolen arts, and these includes oil paintings, gold, silver, ivory, mother of Pearl, brass, you name it, all displayed. It was as if he and his girlfriend lived inside of a treasure chest. It is like an image that I hold in my mind. He called himself though he was broke, living in his mother's attic, he thought of himself as the richest person in the world, if you use beauty as your measuring stick.

Arun Venugopal: Some of these works, they're by household names, and when we're talking about artistic greats, right? He's stolen stuff that was made by people who are very famous, right?

Michael Finkel: Right. Now, everybody, of course, if I ask all your listeners to close your eyes and imagine the thing that you find most beautiful, we're all going to have different answers, ranging from maybe Sunset over the Rockies, to a lover, to a Picasso, but he particularly loved late Renaissance and early Baroque artwork, and that is the 16th and 17th century, and yes, if you are familiar with the famous artists of that era, like Dürer, and Cranach, and Watteau, and Boucher, these were $50 million, $60 million, $70 million oil paintings that he would steal. It was the time when artists broke away from church strictures, and could paint more scenes of everyday life, and he loved those vibrant-- the oil of course, as opposed to temporal, really brings out that shine. He was obsessed with these works of art. He had a collection worthy of a couple of rooms of The Louvre.

Arun Venugopal: You get a hold of what it's sort of like this psychiatric profile of him, and the psychiatrist, I suppose, determines that he's not a kleptomaniac, right? This is a fascinating revelation that gets at his motivations. Tell us a little more about this.

Michael Finkel: Eleven years of work on this, we eventually built up enough trust that Breitwieser gave me signed-written permission to see his psychology reports. I read pieces of five psychology reports, and yes, I don't want to get too into the weeds on psychological diagnoses, but kleptomania s usually highlighted by-- first of all, it's the theft that's really what you're motivated by, not the object, and afterwards for a kleptomaniac, it's usually followed by a letdown steeped in shame or regrets, but Breitwieser was completely the opposite of that. He was very specific about what he stole, and he was exultant after he stole it, so that didn't hold any water.

It was very hard to pin a diagnosis on Breitwieser. He clearly isn't a run-of-the-mill person. He is an outlier. One of the interesting things that all five psychologists said, but besides calling him a cancer on modern society and being quite harsh on his behavior, they all admitted that it was clear that Breitwieser, the art thief, was obsessed, was a true art thief, who truly felt a connection. Love is not too strong of a word to the pieces of art in his "collection," his loot that he stole.

Arun Venugopal: Then you get this contentious, I suppose, highly debatable theory as to whether he suffers from this thing called Stendhal syndrome. What is that, and where do people land when they say whether or not he actually did experience this response, this clinical diagnosis, if you will?

Michael Finkel: The French writer Stendhal, wrote about in one of his books, becoming absolutely overwhelmed with emotion in looking at a Fresco in Florence, Italy. It was so overwhelming that he thought his heart would explode, and he had to run out of the basilica to calm himself down, and then a chief psychiatrist at the main hospital in Florence noted that there were several other people who would become overwhelmed with the beauty of art in Florence, and she named the syndrome Stendhal syndrome. Now, I must tell you, it is not in the DSM, it is not an official diagnosis, but Breitwieser himself, who was an avid reader of art theory and art history and art thieving.

He had his own name for this encounter with art that was just emotionally like a volcano, and he called it a coup de coeur, which is a blow to the heart. He said that when he read about Stendhal syndrome, it was like all the tumblers in a lot clicking into place. He thought his coup de coeur, his blast to the heart, was exactly the same thing as Stendhal syndrome. In other words, there are those of us who become overwhelmed by something we find beautiful and basically faint. I think we've all experienced at least tinges of that when looking at something utterly sublime or what we find beautiful. Like I said, whether it's another person or sunset over the Rocky Mountains or your favorite van Gogh.

Arun Venugopal: I'm talking to author Michael Finkel about his book, The Art Thief. I guess, the world's most prolific thievier of art. [laughs] $2 billion, that's a lot of stuff. You actually get at something I found very interesting is that there a lot of people think it's just BS, this whole Stendhal syndrome. He's just making it up, but one of these experts says, "He has no record of lying. He tends to be quite honest." Do you think fondly that himself believes that this is the reason for this lust for stolen goods and stolen art, beautiful things?

Michael Finkel: I cannot crawl into somebody's mind but 11 years is a long time to work on a project. We spent many, many, many afternoons together. There's no question in my mind that Breitwieser was obsessed with aesthetics and love to surround himself with beauty. I think your listeners might be wondering, how can you steal so many times without getting caught? The answer to that, despite the fact that we have dedicated police forces in 20 countries, specifically working on art crime, including the FBI's Art Crime Force, 20 full-time detectives.

The reason why Breitwieser and his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine, were never caught is that they didn't try and sell the works of art. It's one thing to take it out of a museum, that's risky, but it's even more risky to try and monetize your theft, which 99.9% of real art thieves do. Don't think about this Thomas Crown Affair. Those are fictitious. Very few steal art. In fact, almost none steal art for the aesthetics of it. The fact that Breitwieser put them up in that beautiful treasure chest, his attic bedroom, police were waiting for a transaction to arrive that never came. That's why he was able to get away with it for so long.

Arun Venugopal: You mentioned the people who regard him as this cancer on society, but does he also have a following, people who just think this guy is incredible because of his success rate, if you will?

Michael Finkel: When I choose a topic for a book-- Listen, I admire the heroes of the world, the freedom fighters, and the frontline soldiers, and the nurses. Those people are a distant star to me. They're pure and amazing. I'm interested in the all shades of gray, the scallywags, the miscreants, the rule breakers. I feel when writing something like that, a reader shouldn't be told what to believe. I feel like the reader should act as jury.

If you read The Art Thief, and you decide that Breitwieser is a horrible person, I think that's correct. If you decide that, "Wow, he's to be admired on some level." I think that's correct as well. I'm telling you what kept me motivated writing this story for so long, is that even now, more than a decade into this project, finally seeing a book completed, I'm not sure how I feel about Breitwieser. It's like every question you ask, I'm like, "Oh yes, I like him about that." Then I'm like, "He's an ass about that."

Public museums. I've been a museum-goer since childhood, are one of the great goods of public society. We could talk about the problems of society 10 years from now, but museums are not one of the problems. They allow us to see the most amazing works of art humans have ever created and for a modest admission fee and Breitwieser abused that trust. I waver between admiration and disgust. I wonder where the readers lie down. Welcome to contact me through my website. If anybody wants to, let me know.

Arun Venugopal: You get into his upbringing, which is complicated, I guess. Tell us a little about that and how it set the stage for this eventual path that he took.

Michael Finkel: Breitwieser grew up in Northeastern France in the Alsace, into a fairly wealthy family. His father had an amazing art collection of oil paintings and ivories and antique weaponry. When Breitwieser was a teenager, his parents had an extremely contentious divorce. His father left the family and took all of the artwork, which he had inherited from his side of the family. He didn't leave a single piece for Breitweiser.

His initial motivation, he says, was to try and replace the works that his father had taken. In fact, his first several thefts were similar to things his father had owned, except, as Breitwieser pointed out to me, much more valuable and much better. After 5 or 10 thefts, when his collection, as Breitwieser called his loot, far exceeded his father's, he not only didn't stop, he didn't even slow down. The excuse of replacing your father's collection and the divorce is exactly that, somewhat of an excuse that is no reason to de-robe museums across Europe for more than a decade.

Arun Venugopal: Then at some point in his early 20s, he actually takes his first thing. Well, that was some little village museum.

Michael Finkel: One of the things I'd like to add is that there's theft after theft described in this book, but really what gives, I think the story some heart is that there is a love affair shot through the middle of this. Breitwieser, as his father abandons his family, he meets this woman, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus. I spoke to many people that knew the couple, and they all said, "Oh, this is an unhealthy relationship. This is a terrible meeting of two people."

Everybody said the same thing that they fell in love with each other. Breitwieser fell in love. Anne-Catherine fell in love, and together, they formed this unstoppable art-stealing team. Yes, the first few things they stole together in small-town museums were weapons, somewhat like his father owned, but then just something about the power of love and the bizarreness of criminal connection just really sent these guys into a crime spree. Really like nothing else in the annals of all crime history.

Arun Venugopal: His motivation, you've established, what is her motivation for doing this?

Michael Finkel: Anne-Catherine, who liked the artwork, I think she was somewhat thrilled by the heist. Think about life with Breitwieser. They averaged one theft every 12 days for more than eight years. That's incredible rate. Then they lived in Alibaba's cave, and they had this amazing four-poster bed in the middle. Anne-Catherine was a nurse's assistant. She had a very difficult job, changing bedpans and cleaning, swabbing rooms. I think this allowed her to escape into a fantasy life, literally living like a queen with her king. I think that fantasy life for at least a while fulfilled her. Then, of course, like any good Icarus story, the wings melt, and everybody crashes to earth.

Arun Venugopal: The wild thing is yes, they have all this beautiful stuff around them, but as you have written, they still have to scrape by to provide for other things. Wasn't she ever saying, like, "Can we please just sell one little thing, so we don't have to do this kind of work for the next few years?

Michael Finkel: Well, I think they were both aware that selling the art would really expose them to punishment. [chuckles] She did actually say, "Can you get a freaking job?" Breitwieser, who was a basically a full-time art thief, and when he wasn't planning or stealing, he was researching and reading. He was an autodidact of the highest degree. He got occasional temporary jobs, waiting tables, loading trucks, and they were broke. They had billions of dollars worth of art. On his getaway drives, he had to avoid paying highway tolls. That's how broke he was. He lived in his mother's house. She stocked the refrigerator. It was this odd melange of extraordinary riches and complete poverty.

Arun Venugopal: There's a great term that I think you coin when he's like, "I guess, implicating the public or what do they understand? These people, they are all aesthetically impotent." I think is what you say. I think like, "Oh, that's great. I can always imagine the ads. Do you suffer from aesthetic impotence?" I was just wondering, but what does this mean to him or to you when you're describing his view of the world that seems to not understand what he's all about?

Michael Finkel: I was wondering what the name of the pill to cure that would be, but we'll put that aside. I think another thing that besides a love story and a whole bunch of heists, I'm hoping that if you read this book, you might come away, you might actually learn something from The Art Thief, which is how to enjoy a work of art. more than you ever have before. I think when we stand in front of something in a museum we all naturally tend to intellectualize, talk about paint strokes and symbolism, and all this stuff. Breitwieser, to put it simply, led with his emotions. He was highly educated on the works of art but just wanted to feel the work of art. I think most of us after the age of 10 lose that feeling.

He was horrified by paintings of war. He was rapturous in front of religious paintings, and he was turned on in front of sexy paintings. Having toured through multiple museums and churches with him, he imparted in me, this new way of looking at our answer to me. That is the number one thing that came out of all this research, which is, "Yes, the thefts are fun. The love affair is bizarre. The denouement, the crash, is tremendous, but the advice on how to interact with the work of art is for life," and has changed my aesthetic appreciation of the world.

Arun Venugopal: Last question. How did he get caught?

Michael Finkel: Well, I mentioned that most people get caught when they try and sell something. 201 thefts without getting caught, that is an amazing streak, not just an amazing streak, unheard of in the annals of art crime. He's human. He made a mistake. It's almost funny he was caught one of the few times he was near a museum not wanting to steal.

His girlfriend Anne-Catherine became increasingly nervous about the thefts logically, and she insisted that he erased his fingerprints from the theft. They went back to a museum to erase their prints, and it was that mistake that causes the downfall and his collection. What happens with his mother and his girlfriend is, I believe, as spectacularly unpredictable as his rise. It's got a whole second part this crazy story.

Arun Venugopal: For those of you who actually buy the book, or read The Art Thief, a true story of love, crime, and a dangerous obsession. Michael Finkel, thanks so much for joining us today.

Michael Finkel: Thank you for the perceptive and fun questions. I appreciate it.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.