A New Set of Rules for Major League Baseball

( AP Photo/Morry Gash )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC, I'm Alison Stewart. Baseball's opening day is a whisper away and things are going to look different again. Over the past couple of decades, the play at a Major League Baseball game has been more gummed up than a tub of Big League Chew, the endless batting glove adjustments, the ceaseless pickoff attempts, more calls to the bullpen. The result has been fewer runners getting on base, longer games, and fans heading for the exits, both in the stadiums and with their TV remotes. It's a bit of an existential crisis for MLB, so it's making some changes for the 2023 season.

Joining us now to talk a little bit about it is Evan Drellich. He's a senior writer with The Athletic and the author of Winning Fixes Everything: How Baseball's Brightest Minds Created Sports' Biggest Mess. Evan, welcome back.

Evan Drellich: Good afternoon, Alison. Thanks for having me.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, if you have questions about the new rules or comments, give us a call, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can also reach out on social media, both Twitter and Instagram. It's the same handle, that's convenient, @allofitwnyc. Before we talk about the new rules, Evan, let's talk about the issue that MLB's trying to solve. Longer games, fewer runs, more strikeouts, equal less action. I wonder, how did this time creep happen?

Evan Drellich: I was looking this up right before coming on here, and you have to go back to 2011 for the last time that Major League Baseball averaged a game time under three hours. The peak was in 2021, it was 3 hours, 11 minutes, and it's really an outgrowth of Moneyball, which was a fantastic book and brought a lot of innovation and progressive methods into the sport.

As everybody became efficiency-minded, they started figuring out, "Well, okay, what's most valuable?" Baseball's a great game, but it was not a perfectly designed game. They realized that home runs are incredibly valuable, and for hitters, it doesn't really matter if you strike out. Conversely, for pitchers, you do want strikeouts. You want guys who miss bats as much as possible.

We had this growth in home runs, strikeouts, walks as well, and all that adds up to, A, longer games because hitters aren't putting the ball in plate very quickly. B, without the ball in plate, you don't have a lot of action. It's just a lot of guys walking up to the plate, swinging and missing or hitting a home run. It's boring, and they finally realized at the commissioner's office that they needed to get ahead of this, that the teams weren't going to do it themselves, and they needed to make some changes.

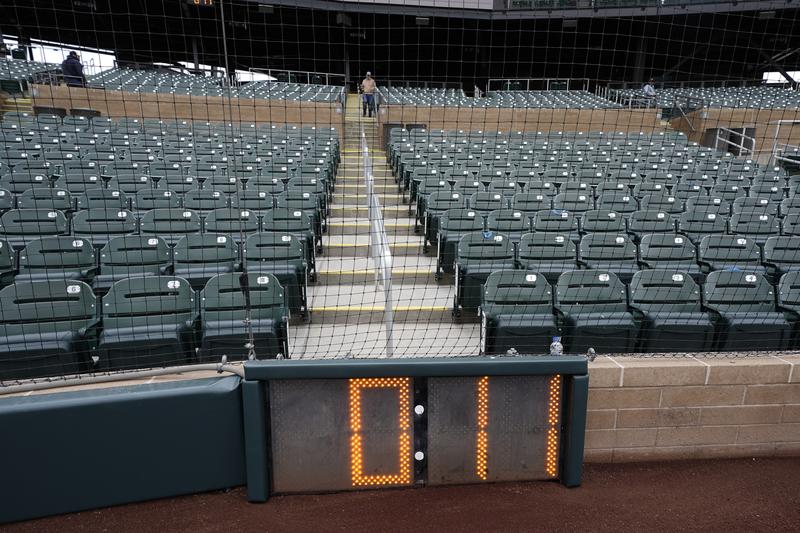

Alison Stewart: All right. Let's talk about some of the rules. The pitch timer is probably the best known. Could you explain the components of the pitch timer?

Evan Drellich: Yes. MLB wants to call it a pitch timer. Most people call it a pitch clock. I'm not sure why MLB wants to avoid the clock terminology. Maybe because baseball traditionally did not have a clock. If there's nobody on base, the pitcher has 15 seconds to deliver the ball. If there is somebody on base, they have 20 seconds. There's all sorts of other clocks involved here. The catcher has to be in the catcher's box with nine seconds left on the timer. The hitter has to be alert, staring out at the pitcher with eight seconds left, the inning breaks at least for regular season games, not the national broadcast will be 2 minutes and 15 seconds. Everything is designed to keep things snappy, and they saw positive results in the minor leagues with this.

Alison Stewart: The shift has been eliminated. Explain the shift for us and what the new rule says.

Evan Drellich: Beyond the clock, we have the defensive shift, which was where you would, as a team, position your fielders in an unorthodox way. Often, it would be for a left-handed batter, you would put your infielders maybe three infielders on the right side because left-handed hitters are often pole hitters. They've banned that now. That means that a ball that used to be going back a couple of decades, traditionally it hits, say, that line drive right up the middle, a sharp ground ball right up the middle.

Teams had started positioning fielders perfectly because they had all the data. After Moneyball, they figured out, "Okay, where should we put guys depending on a different hitter's tendency?" The shift is now banned, you have to keep two fielders on either side of second base, two on the left side, two on the right side.

The bases, physically, the bases that the players run around are now larger. They did that, one, for a health reason. It makes it a little safer, so they give a less chance of the collision, but also makes it a little easier to steal a base. Stolen bases are exciting. They want to bring those back. There's also now restrictions on how many times a pitcher can throw over. Guy gets on first base, you don't want him to steal, well, you can't throw over there now five times in a row. You have two, and then it can reset depending on what happens, but two per plate appearance.

Alison Stewart: All right. I've got a couple of questions I want to tease out. Our baseball fans here at All Of It are saying, "The shift is going to be a huge CHANGE." Why is it going to be a huge change?

Evan Drellich: It's going to make some hitters who were really on the outs, I think, in the last few years better because often, these left-handed hitters, they could just stack the fielders on the right side. Even if it wasn't like that, even if they figured out, okay, this guy has a tendency to be more up the middle, well, you could stack people up the middle.

It'll return it to the aesthetic that we used to have where, okay, you hit the ball really hard to certain spots on the field, up the middle in the hole, chances are now, it'll be a hit. They can still try to circumvent it a little bit. You can bring in an outfielder, but teams are probably not going to do that as much because then you're more liable to give up an extra-base hit. You want your outfielders because you don't want to give up a double or a triple.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about the base size increase from 15 to 18 inches. To explain why MLB made a video imagining the thought process of both the hitter, in this case, Daniel Vogelbach, when he's on base, and the manager, Buck Showalter watching in The Dugout. Take a listen.

Daniel Vogelbach: These new bases are wider than the old ones.

Buck Showalter: Is he focused on the size of the new bases?

Daniel Vogelbach: Now, it'll be easier to steal second base.

Buck Showalter: Is he thinking about stealing second base?

Daniel Vogelbach: Seven years in the league.

Buck Showalter: He's never stolen a single base. Don't steal second base.

Daniel Vogelbach: The pitcher's not looking.

Buck Showalter: I am not looking.

Alison Stewart: All right, is that about stolen bases?

Evan Drellich: The commercial's funnier with video because Daniel Vogelbach is a very, very large burly man who is not going to be stealing any bases. It's interesting that MLB is leaning into this display, that they're actually using these changes as a form of advertisement. They have other commercials that they're putting out right before opening day, alerting people to the new rules.

Stolen bases, again, a product of Moneyball, they figured out, well, unless you're stealing at a very, very high rate, it's not worth it. Teams got away from stealing bases. Now, you make it literally just a matter of inches closer, a little bit easier to steal a base. The bases used to be 15 inches, now they're 18 inches. They're a little larger, gives you a little bit of a jump that you might not have had previously. They saw in the minor leagues that there was an increase in stolen bases. They're hoping that carries over to the majors, that you get a little bit more of that excitement of, "Oh, will he run, will he steal that bag?"

Alison Stewart: My guest is, Evan Drellich, he's senior writer for The Athletic and also the author of Winning Fixes Everything: How Baseball's Brightest Minds Created Sports' Biggest Mess. We're talking about some of the new rules maybe to speed up the game a little bit. I understand even bat boys and girls have to step it up.

Evan Drellich: MLB just put out a memo. They put out several this spring because they're modifying and learning as they go here. The memo was clarifying some of the new rules. One of the things that was included in this memo was that they will be monitoring "the performance of bat boys and girls as the season goes on" because to have these clocks run effectively, a lot of people have to be on, forgive the pun, on the ball.

You have to have the bat boys and girls retrieving equipment and foul balls quickly, because if they're delayed, well, then everything else is going to get delayed. There's going to be an individual operating the clock in every ballpark, and that person's got to really be paying attention. Nevermind the fact that the umpires have to be paying attention. The players have to be paying attention here. There's a lot of moving parts here, and bat boys and girls are going to be a little bit more in the focus than they might have been otherwise.

Alison Stewart: Have any of these rules been implemented to ensure player safety to make it a safer game in any way?

Evan Drellich: The bases is probably the one that health comes up with because, really, it's about first base where often, or not often, but sometimes you'll see a runner and a fielder are converging at first base at the same time. The base isn't that large. If you give a little bit more space, well, maybe that means a base runner is not going to be stepping on a guy's ankle. It hopefully puts a little bit more distance between injury is the idea with the bases, along with incentivizing steels.

Alison Stewart: Somebody on Twitter asked this question. I'm not sure this is your wheelhouse, but I'll read it anyway in case it is, Evan. In terms of growing viewers, MLB TV, Blacks, our local teams, which prevents local fans from being able to watch their teams on MLB's own app. Why can't teams sell direct access to the fans bypassing cable contracts and such?

Evan Drellich: Fortunately, this is my wheelhouse, and I actually can empathize here because I live in New York City. I live in Queens. I am a subscriber to YouTube TV and I cannot watch Yankees games. I also can no longer watch MLB network. That was a carriage dispute. The whole cable RSN model in baseball and in sports in general, but particularly baseball, is built on exclusive carriage agreements. The team has an exclusive deal with the regional sports network, so that's SNY if you're the Mets, Yankees are the S network. Then those entities, the RSNs have deals with distributors, Time Warner Cable, Spectrum, whoever.

There's exclusivity involved in all of it. What's happening now is MLB finally seems to be realizing, "You know what? As cord-cutting is going on, and people are moving away from the traditional bundle, we do need to make these games available to anybody anywhere. It is ridiculous that Evan Drellich cannot watch the Yankees if he wants to tonight."

They have a couple of things they've got to achieve here, though. They've got to either renegotiate or wait for these current contracts to expire. We don't know publicly the full list of where all these contracts are at, but it's going to take years. They're working on it. They want to get to a point where wherever you are, whatever city you're in, you want to watch a major league baseball game, you can pay for it. I would agree, absurd, that they're not at that point yet, but it all ties back to the economics of the cable industry and the evolution of baseball for the last few decades.

Alison Stewart: How are the players feeling about these new rules?

Evan Drellich: Mixed. I think some players have seen it-- have positive impacts to spring. Even this spring, we've seen game times drop really along the same lines as what MLB saw in the minor leagues. It was about a 25-minute difference, and at least as of a few days ago, that's what it's been in spring training. The average time of game in spring training this year, 25 minutes fewer or so compared to last year. That's good.

The players, though, they did object to everything but the bases. That's not because they necessarily thought the clock was a bad idea or that banning the shifts was a bad idea. It's that there were elements on the edges and the margins that the players in their union did not believe MLB was sufficiently listening to them on. We're going to see the presence of a pitch clock in the post-season in the playoffs. That's something that's been a major topic. There could still be some controversy here. In fact, I would bet a good amount that there will be controversy both in the regular season and the post-season.

Alison Stewart: Pete from Wilton, Connecticut has a question. Hey, Pete, real quick. What's your question?

Pete: Hey. Hi. What are the penalties for not abiding by any one of these time limitations?

Alison Stewart: Penalties?

Evan Drellich: It depends on what it is. A pitcher can be awarded a ball if he hit-- well, awarded is the wrong word. Punished with a ball, a hitter can be discredited or credited a strike, however you want to look at it. In the case of throwing over to the bases, if a pitcher does that more than two times per plate appearance, and he does not record an out, so if you try for a third time to get a guy at first base, then you get a bulk. It really depends, but predominantly, the penalty is a ball for pitcher or a strike for a hitter.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Tony online, too. Hey, Tony, real quick.

Tony: Hey, guys. I just wanted to say I know bases in American institution, but it is at its core entertainment and you've got to keep it moving and it's a business, and entertainment's business first and foremost. What do you think about that statement?

Evan Drellich: 100%. I think that's what MLB-- and the commissioner's office seems to be grasping that for a long time. Still to this day, maybe it will always be this way. The teams and their general managers, they don't look at it that way. They're not thinking, "Well, what is the most entertaining thing we can do?" They're thinking, "What is the roster I can build that will win the most number of games?" That has a cumulative effect. When you have this group think that took over the sport, and that's why you ended up in a place where the game had become less entertaining. Yes, this is about making sure it is entertaining so that they have fans and paying customers.

Alison Stewart: How will we know the measure of success? Fans, ratings?

Evan Drellich: I think, yes, there's a lot of different ways. I had an interesting conversation the other day with a company called CrowdIQ, and they have cameras in different professional sports teams, parks, and not just baseball, but one of their insights from baseball is that people leave games sooner. This varies a bit market to market than they do in the other sports. One area we could measure potentially throughout this year is, "Well, okay, are people staying longer?" If football and basketball and hockey are more captivating for people, does baseball get to that place as well?

Alison Stewart: Evan Drellich is senior writer at The Athletic. He is the author of the book, Winning Fixes Everything: How Baseball's Brightest Minds Created Sports' Biggest Mess. Definitely check it out at your local indie bookstore. Evan, as always, thanks for your time.

Evan Drellich: Thanks, Alison.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.