New Exhibition Celebrates the 50th Anniversary of Hip Hop

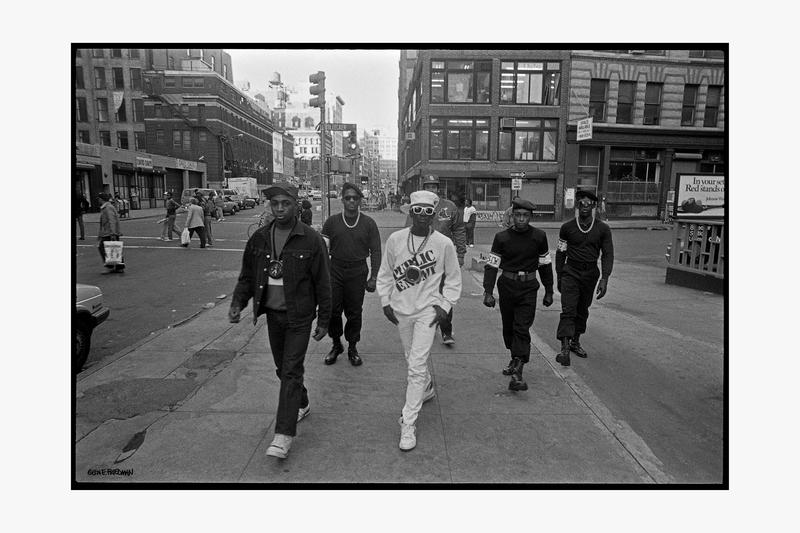

( Photo by Glen Friedman )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on demand, I am grateful you are here. On today's show, we'll talk with Emily Nagoski, a co-author of the book, Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle. If you're thinking about starting your own business or maybe making your side hustle your main gig, we'll talk about how to become an entrepreneur with two experts. It is Grammy week, the awards are on Sunday, so we'll hear from pianist, Robert Glasper, who is nominated this year. That is the plan. Let's stay with the music theme and get this started with a conversation about the exhibit, Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious.

[music]

That mix right there that DJ Kool Herc put together in August of 1973, it started a music revolution that is now being celebrated with a two-floor photo exhibit at Fotografiska. It's called Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious. What started in the Bronx 50 years ago, has become the most listened to genre in the US. Its evolution is documented in more than 200 photos, plus some throwback video for fun. Not only are there photos of artists like DMX, Jay-Z, Salt-N-Pepa, Slick Rick, Pop Smoke, and Lauren Hill, among others, the show also features photos of the neighborhood where hip-hop was born and the people who originally consumed it.

The show also pays tribute to graffiti artists, the distinct styles and flair of each region. A Vogue review states, "Portraits of the genre superstars, Biggie, Tupac, Public Enemy, De La Soul are balanced by photographs of people whose names we don't know, acknowledging the communal quality of the four elements of hip-hop, emceeing, DJing, B-boying, and graffiti writing. Today we are joined by the exhibition's co-curator, Sacha Jenkins, is the Chief Creative Officer at Mass Appeal. Welcome back, Sacha.

Sacha Jenkins: Thanks for having me. Always great to be here.

Alison Stewart: Sally Berman, the visual director at Hearst Visual Group. Sally, nice to meet you.

Sally Berman: Nice to meet you too. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, what was the inspiration for the title, Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious?

Sacha Jenkins: When I was growing up, hip-hop was something that we just did. There were no record labels, they weren't people getting rich, it was just part of our day-to-day. We played stickball, we played handball, we might write a little graffiti, breakdance, and rap. That was a time when hip-hop was not conscious of itself. We didn't understand who we were and what we were outside of just expressing ourselves. Then there was a time when hip-hop became conscious of itself, and there were careers and industries and fortunes built on the backs of this culture that came from very humble beginnings.

Alison Stewart: What's interesting, I was with a friend yesterday, we went to the exhibit and he said, "Man, wasn't it great before stylists?" [laughs] Stylists are great. No disrespect on these stylists out here but, Sally, there's just a certain authenticity in some of the earlier photos that is incredibly charming and, in some ways, heartwarming.

Sally Berman: Absolutely.

Alison Stewart: Your expertise as a visual director and art director, how do you tackle a project as large as 50 years of hip-hop imagery? Where do you start? How do you think about organizing a show like this?

Sally Berman: It's overwhelming. Five decades is not a short amount of time. I think I have that brain set. I've always been an archivist of sorts. We started by making a list of the rappers we wanted to include. We made a list of the photographers that we knew, and wanted to just have a really balanced view of all the different regions. It was a lot of back and forth, several meetings, going over lists and looking at images, and seeing who we had were missing.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, some of the first images aren't of musicians and artists, but locals in the neighborhood, members of the Savage Skulls. Why was this an important jumping-off point for the exhibition?

Sacha Jenkins: Because hip-hop is people. If it wasn't for the people, there would be no hip-hop. It's not all about big brand-name rappers, it's about people who were known in their communities. Some are more known than others, but I wanted people to really feel what hip-hop- where it came from. It just came from very humble beginnings and everyday people on the street who wanted to express themselves.

Alison Stewart: Sally, this is-- [crosstalk]

Sally Berman: So many of them are kids.

Alison Stewart: Yes, continue. Go ahead.

Sally Berman: No, I just wanted to point it out, if you look through the show, so many of the photographs of really young people that started this movement.

Sacha Jenkins: Going to the Savage Skulls, for instance, gang culture was thriving in 1973. I don't want to romanticize and say that hip-hop eradicated gangs, but certainly, the energy, the competitive nature of the gangs, you have these insignias of the gangs on the back of their jackets. When you look at the breakdance battles and stuff, they would have insignias, the names of their breakdance crews on their jackets. They're not battling over turf, they're dancing. I wanted people to understand the energy that was on the street, how that transferred over to the culture.

Alison Stewart: My guests are Sacha Jenkins and Sally Berman. We're talking about Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious. Now at Fotografiska. Sallly, there's a real mix of styles in the show. There are portraits, there are candids, there's some super hyper-stylized work, like the work of Sam Balaban, especially at the end. Would you share an example of perhaps one of the most stylized images we see, and then maybe an example of one of the most raw and unaltered images? Just to give people a sense of the breadth.

Sally Berman: Yes, of course. There's a group shot of Wu-Tang by [inaudible 00:05:51] where they're charging out of the water. It's very stylized. They couldn't have been done without budgets for retouchers and lots of concepting and probably sketching. Then you have much rawer photos of kids tearing their cardboard across the street to dance. It's very unguarded. No one really knew what was the influence that it was going to have.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, the legend goes, DJ Kool Herc laid the foundation for hip hop at a party in the Bronx in '73, where he created this continuous track using two turntables and different pieces from different pieces of music. First of all, what actually happened that night? Then maybe more importantly, what happened next?

Sacha Jenkins: I certainly wasn't there in the '70s. I was two years old, but what-

Alison Stewart: As the legend goes.

Sacha Jenkins: -happened that they threw a very humble party in the basement of their building, and that party became the marker for the birth of the

culture. The truth is, listen, you got to start somewhere, but I believe that whether it's blues, jazz, gospel, Black music in America, it's a continuum. Hip-hop is just a marker of a certain period of time in Black American, in American history but you've got to start somewhere. That party has become known as the beginning, but I believe the energy predates that. The hip-hop energies, blues energies, is jazz energies, it's the same thing, just reimagined every generation.

Alison Stewart: To your knowledge, what happened next? The sound is being created or is being recognized, when does it start to become mainstream?

Sacha Jenkins: You go from Studio 54 is happening and our Studio 54 happened in the parks, so you have more DJs playing music outside. DJs becoming known for their style of DJing, and the people who would show up to these parties. Eventually, these folks started to make tapes of their performances. You weren't at the show, but eventually, the tape of that show made its way around.

Then eventually, someone decided that it was time to record this kind of music, committed to tape and committed to vinyl. There's a guy named King Tim III, which is often credited as the first rap record, which I dropped in '78. Really, I think Sugarhill Gang, Rapper's Delight was the thing that, the lightning rod that really shot her around the world. Once that happened, record companies and other industrious people figured out like, "Hey, people want this music." More and more of it got recorded, and then eventually, music videos and clothing lines and everything else followed after that. That was 1980s. Rapper's Delight, I believe this was '79, '80.

Alison Stewart: Sally, the list of photographers is really interesting. When you think about the careers of some of these photographers, how did they end up documenting something which was still underground, at least in the early days? Then, how did the idea of being a music photographer who takes pictures of hip-hop evolve? [crosstalk] When you have somebody like Janette Beckman, I know she heard it in the UK and was completely drawn to it and had to come to the States. This was her whole goal was to take pictures of hip-hop artists.

Sally Berman: Yes, she started by shooting punk artists, and then coming to the US to shoot rappers. I think there's a lot of that in the show. A lot of European photographers were coming over here and documenting it. Now, things have shifted, it's all over. It's much broader spectrum of photographers. We have photographers now shooting that are not necessarily only shooting music or only shooting hip-hop.

Alison Stewart: My guests are Sacha Jenkins and Sally Berman. We're talking about Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious. Sacha, the show considers Emceeing DJing, breakdancing, graffiti, beatboxing. How does this exhibit weave those elements together?

Sacha Jenkins: You see how it all coexists and how it wasn't a conscious thing. Like the breakdancers who were breaking, there just happened to be a beatboxer there. It's not like it was a conscious thing, it's just this all very naturally came together. There was a Village Voice article that dropped in 1980, which crystallized hip-hop as a culture. The article basically said, this rapper, plus this DJ, plus this breakdancer, plus this graffiti artist makes hip-hop.

There are people who will tell you that they were writing graffiti in 1973, and that they listened to Black Sabbath. They don't have anything to do with the Sugarhill gang. In many ways, hip-hop came together in a way that was very organic to what you believe. For some people, graffiti isn't a part of hip-hop, but for others it is. If you subscribe to this a la carte, coming together of all these things, then yes, it is your hip-hop does involve all of these elements, but for many people, it doesn't. I don't know if I've answered the question, but maybe presented a theory more than anything else.

Alison Stewart: Sally, there are more 20 female artists included in the show. What conversations did y'all have about how to represent women in the exhibition?

Sally Berman: We knew that female rappers there's way less than there are male rappers, so we really wanted to showcase them, but not necessarily highlight them and really show them in how they were probably perceived and how they were seen when they were coming out. We wanted to show them in all their shine, but also not single it out.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, will you--

Sally Berman: Obviously, include as many female photographers as possible. There were quite a few.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, when you think about the evolution of women in hip-hop, how would you describe it?

Sacha Jenkins: I would describe it as women continuously being marginalized by men. I think that women are stronger than ever nowadays in the industry of rap, but I think they've been marginalized since day one. It's great that we are able to make sure that they are represented in the show.

Alison Stewart: There's some great ephemera in this show, Sacha, like, there's a great 8-track tape, there's a whole wall of cassettes. Do you have a favorite piece that's not a photograph in the show, something that you'd like people to spend an extra few minutes in front of?

Sacha Jenkins: The 8-track that you mentioned blew my mind because I had no idea hip-hop even made it to 8-track. Those 8-tracks must have happened in 1980 because I think 8-track was definitely on the way out by 1980 and hip-hop was on the way up, but those are the earliest, only known 8-track of hip-hop in existence. It's pretty cool.

Alison Stewart: Where are they from, if I can ask?

Sacha Jenkins: Pete Nice of the Rap group, 3rd Bass, who's also a crazy hip-hop historian, who's working with the Hip Hop Museum, I believe it comes from his collection. He lent it to us.

Alison Stewart: Sally, do you have a favorite piece in the show that's not a photograph? The photographs are gorgeous, but just something tangible?

Sally Berman: Yes. They're Polaroids, so they are photographs [chuckles], the low life Polaroids that we got from--

Sacha Jenkins: Thurston Howell.

Sally Berman: Thurston Howell, thank you. Are pretty incredible, and they're in one of the first rooms. I really love those. What else do we have that's really great? The Public Enemy Medallion is also pretty amazing to have in our possession. That also came from Pete Nice.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, you know there's obviously artists in the show have had different issues. Afrika Bambaataa has faced allegations of sexual abuse. He's currently dealing with a lawsuit. What conversations did you have about some of the, we talked about it a lot on the show, separating the artist from the art, the person from the art?

Sacha Jenkins: It's 50 years in two floors. The Shaka Bambaataa, I thought was interesting because it was a different look at Bambaataa. He was downtown, he's unassuming. I can't speak to the allegations, but I know that there's a lot happening with it. Simultaneously, he was very important to the birth of hip-hop. It's a delicate balance you want to strike because you want to honor history and you want to honor the truth, but sometimes, history trumps other things that might be going on.

Alison Stewart: Sally, how do you deal with that? How do you think about that as someone who's in the business of art, separating the art from the artist, if you can?

Sally Berman: It's hard. Yes, no, it's hard to separate it, but yes, we did our best to try to document the history as close as we could. Again, as Sacha said, two floors is, we could have filled several more floors, so not everything is included that we'd like to include.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, yesterday, legislators and announced that their Universal Hip Hop Museum in the Bronx would receive 5 million in federal funding to help construct this building and create educational programming. The museum expected to open next year. When you think about educational programming around hip-hop, what would you like to see?

Sacha Jenkins: Hip-hop is always a reflection of and a reaction to the environment, and so I think what's really necessary is history. I think the reason why America's in so much trouble right now is no one's really paying attention to history or people are trying to rewrite history. I think if there was some kind of focus on not just hip-hop history, but the history that's fed hip-hop, because again, hip-hop, jazz, blues, rock and roll is all a reflection of and reaction to the environment, and the environment is going through a lot. Hopefully, there can be some kind of history lessons and things that really unpack what's happening with society. Because it gets unpacked in the music often indirectly, but I think sometimes a more direct approach would be more effective.

Alison Stewart: Sally, is there an image that you're really taken by in the exhibit for its artistry? Not just because-- Some of them are so beautiful and you're like, "Oh, I recognize the person. Oh, there's somebody when they were so young and so beautiful, or there's somebody when they're older and beautiful too," but is there a photo in the exhibition that you really, really admire for its [stutters] artistry? That's what I'm trying to say.

Sally Berman: I love the portrait of Outkast in the elevator. I love the energy of that photograph. I love the color of this photograph. I feel like when I look at it like I'm with them. I really love that image off the top of my head, but there's so many that I feel strongly about.

Alison Stewart: Sacha, for you, is there a certain image that you just really like the artistry of the image making?

Sacha Jenkins: There's a photograph of a gentleman who's no longer with us named Phase 2. He's a very important figure in the world of hip-hop, who's lesser known. He's not a famous rapper, but had many contributions as a fine artist, as a rapper, as just a personality on the scene. There's a very humble photo of him that, for those who know who he is, understand the power of the photo, but I think it's just generally a really great photo.

Alison Stewart: The show is called Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious. It is currently at Fotografiska. My guests have been its co-curators, Sacha Jenkins and Sally Berman. Thanks for spending time with us.

Sacha Jenkins: Thanks for having us.

Sally Berman: Thanks, Alison.

[Hard Knock Life playing]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.