A New Documentary Examines a Risky and Covert CIA Operation

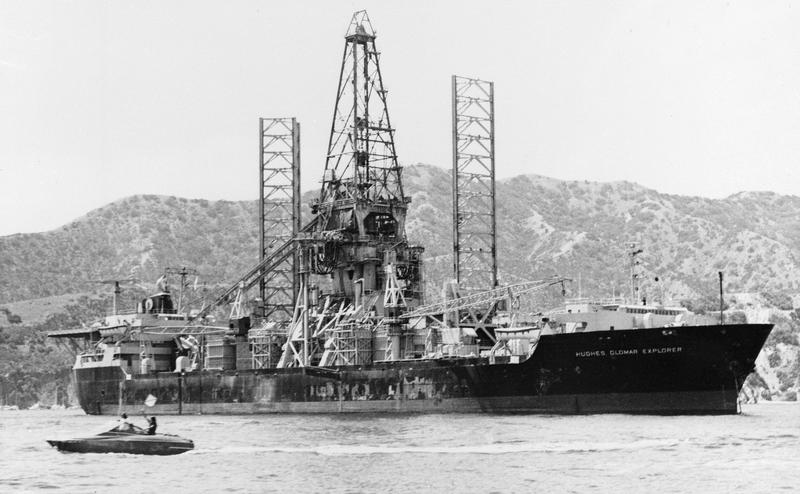

( Catalina Island, Calif., August 29, 1975 )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. On the show next week, we'll talk to the curator of the new Ed Roche exhibit at MoMA. We'll continue our series of Small Stakes, Big Opinion. Wait for it. We're going to talk about where the best French fries are. We will have Pete Wells from the New York Times joining me for that one. We'll also speak with Sterlin Harjo, the co-creator of the amazing FX series Reservation Dogs. That's a peek at what's coming up next week on All Of It.

Now, let's get this hour started with the documentary Neither Confirm Nor Deny. We've all heard the phrase, we can neither confirm nor deny, and now a new documentary reveals the wild origin story of that phrase, and it involves the Soviet Union, the CIA, and Howard Hughes. 50 years ago, the CIA accomplished something that many thought would be impossible. It retrieved part of a sunken Soviet submarine with the hopes to get some intel, but that was 1973 in the midst of the Cold War and spies were everywhere.

How could the CIA construct a machine big enough to haul up an entire submarine without the Soviets or the press finding out? The answer includes countless unknowing mechanics and workers around the globe, Richard Nixon and Hollywood powerhouse Howard Hughes, but the mission was not airtight and once journalists got wind of what was going on, they were desperate to know details. The CIA's response included the now popular phrase, we can neither confirm nor deny, known to history aficionados as the Glomar response.

A documentary titled Neither Confirm Nor Deny was directed by the late filmmaker Philip Carter who sadly passed away recently, but his final film will be available to stream on Apple TV and Prime Video on Friday. Joining us now to discuss the film are producer Sheryl Crown. Hi, Sheryl. Nice to see you.

Sheryl Crown: Hi.

Alison Stewart: We're also joined by--

Sheryl Crown: Lovely to meet you.

Alison Stewart: Lovely to meet you. You're dialing in from the UK, so we're going to have our fingers crossed the connection stays. If not, we will figure out a way to connect back with you. We're also joined by Hank Phillippi Ryan, journalist turned novelist who was a dogged reporter determined to get her hands on more information about this covert mission. Hank, it's so nice to see you.

Hank Phillippi Ryan: You too, Alison. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Sheryl, I gave a short description of the mission to retrieve this submarine, but I'd love for you to fill in a few more details; what the mission's goal was, who was in charge, what it was called.

Sheryl Crown: Thank you, Alison. Yes, this was an extraordinary stranger than fiction real story. The Russians lost, the Soviet Union lost a nuclear submarine in 1969. The CIA found it, the Americans found it, and decided this may have very valuable nuclear information on it, so they did hatch an extraordinary plan to try and retrieve the nuclear submarine three miles down from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean in plain sight with a cover story that would hold.

Actually, the leaders at the CIA worked with extraordinary men. David Sharp was the chief engineer, and actually, we were very fortunate to have access to David to work with him over the years on this story, and those of you watching the film will see him. It was also the most extraordinary story of achievement, engineering achievement, various people like Curtis Crook from global marine mining, and also the extraordinary character of John Parangosky at the CIA who was a rather estranged violin-playing extraordinary individual who would sack David Sharp every other day but then reinstate him.

It's a period of great excitement as a spy story. The mission and the goal was very much to see what was going on with the Russian nuclear intelligence at a submarine level. There was a lot happening in the '70s. It was the height of the Cold War and I think Walter Lloyd who was the guy in charge of the cover story and who actually coined the Glomar response-- He's the person who said, "This intelligence will let us know what the Russians are up to, what the Soviets are up to."

It was deemed a very high-stakes mission, and the guy's intelligence around it, obviously, they threw everything at it. What I love about it aside of the extraordinary mission was the way in which the story really does reveal the brilliance of investigative journalism as well as the brilliance of the CIA at that time. It's a dual story in a sense, and honestly, I could speak for hours but the film does that.

Alison Stewart: Hank, let me bring you into this conversation. As a journalist, part of it is the story of the journalists trying to get this story, but I want to take us back. What was the relationship between the CIA and the press at that time and what's the press's view of the CIA in the late '60s, early '70s?

Hank Phillippi Ryan: I think that's a great question because I think that times were changing quite a bit at that time. I think we as journalists, and I was a very young journalist in Washington, DC at Rolling Stone magazine at the time, I think that our attitude about the government was beginning to change. We had all been a little naive maybe before that, and as the world began to change as there was Watergate and as there were all those kinds of things that were happening in the '70s, we began to be very suspect and be very curious and began to come into our power as journalists, and began to realize that-- and forgive me for this, but we began to realize that the government might be lying to us and the government might be keeping secrets.

Neither Confirm Nor Deny, the documentary, is this extraordinary tour de force in point of view because there were so many puzzle pieces. If you can imagine the CIA and the journalists and Howard Hughes and the Russians and spies. This story, I love that you called it wild in your introduction because it is. If you said to anyone, "Did you know that some years ago the CIA secretly tried to steal a Russian sub from the bottom of the ocean?" People would say, "No, that couldn't have happened." Yet, it did, and the government tried to hide it.

It's a wonderful story, which we can talk about. but in essence, it's the intersection of the public's right to know with the government's right to keep a secret. It tells that story so gorgeously. It's as action-packed and it's intriguing.

Alison Stewart: [chuckles] It is.

Hank Phillippi Ryan: Isn't it? As any spy thriller. We always say you could not make this stuff up and Neither Confirm Nor Deny puts together those puzzle pieces in this sort of-- I don't know, Alison, total immersion history. You are there and hear it from all sides.

Alison Stewart: Sheryl, how did you and your team--

Sheryl Crown: Can I just come in with that on--

Alison Stewart: Yes, I want to follow up a little bit and then let you dive. Oh, we've got this delay. Delays are tough. When you were talking, when you were assembling this group of CIA officers to speak on the record about this, what were some of the guidelines? What were some of the rules and some of the terms that these men, one, could speak, and why did you get a sense that they wanted to speak?

Sheryl Crown: We were very lucky that David Sharp had actually had a book published called The CIA's Greatest Covert Operation. The fact that he'd already got the book out there with his lawyers, he had been-- in a way, the CIA already knew the story was out there. We had no opposition at all to any of our conversations with David, with Walt, or with Curtis, though it was all out in terms of David's book. Also, I think the guys were very proud of what they'd achieved in some way, and so they should be in terms of the technical brilliance.

In that sense, we didn't have to worry that much about the CIA. We do have some CIA classified footage, but that's also in one tiny instance that's been seen somewhere. We have some of the footage and we also have David's original photographs from the mission which he's given us permission to use. We were really actually quite gung ho about it and didn't fit in any way under threat. Interestingly, the only thing I was going to carry on [unintelligible 00:08:46] brilliantly that Hank explained the relationship with the press and the CIA.

We've actually got audio recordings in the film of Colby, Kissinger, and Nixon expressing their anger and their frustration and almost their disgust of the wonderful investigative journalism of Jack Anderson and Seymour Hersh. Seymour Hersh and Jack Anderson were sort of flies in the ointment. They just really spoke very negatively in audio tapes that Phil, our wonderful director, and thank you for letting the audience know that he sadly just passed recently, Phil listened to masses of audio tapes of the White House talking about those journalists.

They did not respect those journalists, but interestingly and maybe Hank can speak more about this, this was a time in which journalists did a deal with the CIA. Colby did a deal with Seymour Hersh to keep the story out of the press on grounds of national security. I'm not sure that would ever happen now, that any journalist and CIA director would come to a deal that said, "Please don't break this story. It's about national security."

Alison Stewart: Certainly not one that said for a year. That was it. It was a year. Please be [unintelligible 00:10:01] if I'm remembering correctly, Hank.

Hank Philippi Ryan: Well, it was a long time. That's exactly where we came in, is that we began to hear that the CIA was telling certain news outlets, asking them please to hold this story and so we wondered. We weren't asking about government secrets. We were simply asking who was being told or asked or made a deal to keep the secret. You have to know very, very quickly I had worked on Capitol Hill and the Administrative Practice and Procedure Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

We worked on the Freedom of Information Act amendments, and I knew the Freedom of Information Act through and through. We all thought if we want to find out what the CIA is doing, why don't we just ask them? The CIA under the Freedom of Information Act, just like every other government agency, had to tell us what information they could that was public there. As you know, there are exemptions to the Freedom of Information Act, and we knew that.

We decided we'll play by the rules. We'll just ask them. We wrote them a letter saying, "Please tell us any and all correspondence documents research," you know how to write a Freedom of Information Act request, "about the government's effort to stop the story of the retrieval of this Russian sub." We thought we were so smart because we knew that there were only two answers that we could get. One, they would say, "This information is classified." That's an exemption to the Freedom of Information Act.

They could say it was classified, and then we would have a story, wouldn't we? Because there was something that was classified, or they could say, "We have no idea what you're talking about. There's nothing like this in any of our files. We just don't have it." We sent off a letter with a stamp in the mail and said, "Tell us this stuff," and waited for the response.

Alison Stewart: My guests are Hank Philippi Ryan, a journalist who is in subject in the film, Neither Confirm Nor Deny. I'm also speaking with the film's producer Sheryl Crown. We'll get to the response in a minute. I do have a tangent. I want to go on for just a moment with you, Hank. Although your name is Hank, you're very much a very beautiful feminine woman. A lot of this was a boy's club. It's Jack Anderson, it's Sy Hersh. What was it like for you at that time?

Hank Philippi Ryan: [chuckles] It was really a heady time in Washington, DC. There was Woodward and Bernstein and Ben Bradlee and Henry Kissinger and Frank Church and the power brokers in Washington. I can tell you this, Alison, maybe I was 24 or 25, and I think I had the naivete of someone that's that young that I just thought I can do anything, I can be involved in this, I know as much as they do, and if I don't know, I know how to find out. It was fabulous if I could say. I felt as if I was really in the middle of history at that time, not only watching it unfold, but being part of it unfolding.

I have to say, watching this documentary, Neither Confirm Nor Deny, I realized that each of us had our role, but we never knew the whole picture. We never knew the whole picture. I'm watching this documentary and thinking, "Really? He said that? They did that? That's what they have? That was actually on tape? Are you kidding me?" It's just a marvelous way of learning more about the world that I was really in. We were brave. We were empowered. We thought we were going to do this, and we gave it our best shot.

Alison Stewart: Sheryl, in order to have this plausible cover story for a giant ship is being constructed and sent to the Pacific Ocean, the CIA needed a reliable partner, someone who would say, "Oh no, that boat belongs to me." It seemed like Howard Hughes. People might believe that of Howard Hughes at the time. Why did the CIA agents think he would be a really good fit for this collaboration?

Sheryl Crown: Okay, he's a perfect partner. This is where it feels-- I work in absolute fiction as well, and this is what I couldn't believe. I would not make this up in a script, but Hughes already had a marine mining operation. He obviously was an individually eccentric guy who had lots of money, was known to be a patriot. He was the absolutely right person to try and work with the government to make this thing happen. He had millions, so he could look as if he could front this original new global marine mining big ship with a hole in the bottom within which they would send Clementine, the claw down, and pick up manganese nodules.

That was the cover story. Interestingly, the CIA and everybody, of course, knew that Howard Hughes was a hermit and wouldn't really talk to anybody apart from his key people. The CIA had real problems trying to get to Howard Hughes. Interestingly, Curtis Crook, who was the guy on the West Coast was involved in the design of the film. The guys on the West Coast who were much more laid back, not CIA, but involved in the mission, they got to Howard Hughes. They got to his people, and therefore, the CIA were able to do the deal with Hughes.

It is a proper spy movie. It's Howard Hughes fronted this five-year mission. There was a big press announcement in Hawaii. It wasn't just a little bit in the press. What was interesting, if you look at the ethics of the CIA and the cover story, because people thought global marine mining was a whole big thing, it started other businesses wanting to get into it, whether the whole thing was a fiction. The whole thing was a fiction. There was no global marine mining happening with Howard Hughes, but businesses thought it was something they should get involved with.

Another funny story because spy stories all have their funny moments or historical coincidences, it's extraordinary that the Howard Hughes's offices were burgled the night the ship took off to recover the submarine. In the offices, they took papers, which could absolutely disclose the fact that Howard signed off on this mission, agreed to do it. The CIA were terrified that these papers would get into the hands of press or other people. There was a ransom note that the CIA thought, "Oh my God, we have to pay this." Howard Hughes's people said, "We are not going to pay this for these papers."

The CIA paid $100,000 or something to get back the papers. It's a classic spy movie scene. They travel with a black bag to a corridor down a dark room, and they get nothing for the papers. They leave the $100,000 and they don't get anything. They were living in fear once the mission had started that somehow the papers would be out there, and it would be proved that Howard Hughes is the front and the cover story for the CIA covert operation. Little things like that you could not make up.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing the documentary, Neither Confirm Nor Deny. It'll be available to stream on Apple TV and Amazon on Friday. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guests are producer Sheryl Crown, former journalist, now novelist, Hank Philippi Ryan. We are talking about the film, Neither Confirm Nor Deny available to stream on Apple TV+ and Amazon on Friday. The very true story, the very wild story of the CIA having a covert mission in the '70s to retrieve a Soviet sub before the Soviets, or the press realized what was going on. Hank, when did the press first get a sense that there was something strange going on with this Russian sub?

Hank Philippi Ryan: I've been trying to think about that, Alison, because I wanted to talk with you about that. You know how a story grows. You hear, especially in Washington, DC, at a party, at a lunch, at a hotel, at a meeting, at a Senate hearing, in the corridors. You just hear a little snippet here and a little snippet there. At some point, the little snippets repeat and repeat and repeat. That's when your story sense opens and you think, "Yes, I think there might be something here." We began to probe and we began to ask, and no one was really answering us.

You know that look of like, "Yes, I don't know. You'll have to ask someone else. I don't really know," that sort of pretend innocence about it, which gave us all the more real reason to believe that something was going on, something that we needed to pursue.

Alison Stewart: Sheryl, by the time the mission was ready, they've got the cover story, they've got this enormous ship, they're ready to go, it had been many years since that Soviet sub sunk. Did anyone consider that, oh, we're going through all of this to find intelligence, but that it could be outdated, it could be useless, or it could be incredibly physically dangerous to the people involved?

Sheryl Crown: Yes, there was a lot [unintelligible 00:19:34] John Parangosky was huge. The CIA had to actually talk to committee upon committee to get the mission signed off, and all those questions were dealt with. In particular, whether the information will be out to date, because it was nuclear, because the submarine was nuclear, what had caused the implosion? Was there a nuclear explosion? Was everybody dead? What state would they find the submarine in?

They'd seen that there was a submarine there, but they had no idea. The feeling was there was bound to be something of value in there and it was worth the mission. I think what came over is the Cold War was incredibly hot at that time. At the same time, Nixon was desperately trying to create world peace and was actually involved in SORT talks at the time. His instruction when the mission actually got signed off was, "Yes, you can do this, but do not bring the sub up whilst I'm in Russia, whilst I'm signing a SORT treaty," because then they would be totally exposed.

There was a lot of fear of the whole thing could blow up. It could actually kill the US guys. They might find that the intelligence was useless. Now, of course, it's still classified. What was actually found was still classified, so we don't know the extent to how useful it was, but David Sharp, and he says this in the film, believes what they found was of some use, whether or not it was worth the $5 billion in today's terms that it cost. I don't want to give away the story. I don't want to create any spoilers here for your viewers.

I think there was a lot of worry about it, but it was deemed still to be a mission that they could and should undertake during this period of Cold War tension, even though quite in a contradictory manner, Nixon laid claim to saying, "This is a time where I want to build world peace." It was very contradictory, but yes, this was important. The Americans had just put a man on the moon, their feelings were quite high. "We need to do something very, very good here."

Interestingly, about what Hank was saying about when did you first hear about the story and what happens in Washington, Hank, this was absolutely corroborated by Seymour Hersh when we interviewed him, when he said Washington-- when he heard the story and he dared to put, "Nuclear submarine, Russian, what's going on," in a Washington room full of people. He said everybody just shut up, and then he knew there was a story.

Then Colby called him the day after and said, "Sy, you have to stop this story. I will give you something that's worth it," and Seymour Hersh said, "Okay," because Watergate was the big story and Seymour Hersh got information. Colby called Sy Hersh after one of those Washington parties and said, "Right, this story has to stop here."

Alison Stewart: Hank, let's talk about neither confirm nor deny, that phrase. Tell us about the day you got that phrase and what you thought when you first read that.

Hank Phillippi Ryan: The mail arrived, and I thought, "Oh, here it is. Here's our response." The letter came, letterhead CIA, that was cool, and I knew that a story was inside. I knew that when I opened that envelope, everything would change one way or the other. It was either going to give us the information we needed, or it was going to say this does not exist. We were about to win.

I opened the envelope, and I think I remember just bursting out laughing, thinking, "Can they say that?" Because the letter said, "We are in receipt of your Freedom of Information Act request," whatever it was, "We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of this information. If it existed, it would be classified, but we are not going to tell you that we have it. We can neither confirm nor deny that we have this information."

We thought there were only two answers, and this was surprise, surprise, the third answer that we had never thought of. I will confess to you, Alison, that after I burst out laughing, I had to give them some begrudging admiration for the wording of that, which I had never heard before. I think no one had ever heard it before. That was the moment when that expression came into being. We all know it now. We all say it every day, but that letter was the moment.

I laughed, and then there was some admiration, and then I got really angry because I knew that we were playing by the rules but the government was not playing by the rules. You could not do that under the Freedom of Information Act. That just propelled us into trying to find out more because, Alison, what they were saying was, to me and to all of us, they were saying, "We don't care what the rules are. Go away."

Alison Stewart: Did you continue?

Sheryl Crown: Interestingly-- May I just jump in there-

Alison Stewart: Yes, absolutely.

Sheryl Crown: -a second, Alison, because one of the things, having met Walter Lloyd, who was the great architect of the covert mission, he was an extraordinary guy. When he talked about how he had to come up with a plan for security, how he had to absolutely make sure this secret was never divulged, he would have oversight. He would talk to two specialists himself on a regular basis to test out his theory of the covert mission.

Walter was an extraordinarily bright man, and sadly, he's no longer with us, but interestingly, when he was approached with Hank's letters of Freedom of Information requests, David Sharp says of Walt, Walt took 15 minutes to come up with this wording. I'll just read it specifically from Walt's words because it's, as Hank said, so annoying but so clever, where he said, "We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested. Hypothetically, if such data were to exist, the subject matter would be classified and could not be disclosed."

This man came up with the Glomar response, which absolutely infuriated everybody, but was actually so smart. In a way, he managed to pull it off, but of course, the story did break. Everybody did break the story, or Jack Anderson broke it, followed up by Sy Hersh's very long article about it, very much prompted by Hank's letters as well. There's a level in which the story by that point was broken, and they had to, in a way. Nobody knows what was found, but it was broken.

Hank Phillippi Ryan: I've always wondered about the man who wrote the letter. I always imagined him and wondered what went through his mind and wondered if it took them days to craft this. The idea that I got to see in this wonderful documentary what really had happened behind the scenes, I have to tell you, and I don't want to give it away, but their reaction to the press's requests for this information was just priceless, is just memorable. I'm so pleased to be able to see the part of the story that I never got to see.

Alison Stewart: Neither Confirm nor Deny will be available to stream on Apple TV and Amazon this Friday. I've been speaking with producer Sheryl Crown and former journalist, now novelist, Hank Phillippi Ryan. Thank you so much for being with us and sharing your stories.

Hank Phillippi Ryan: Loved it. Thank you for having us.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.