A New Documentary Examines the Origins of Black Americans Fraught Relationship with the Police

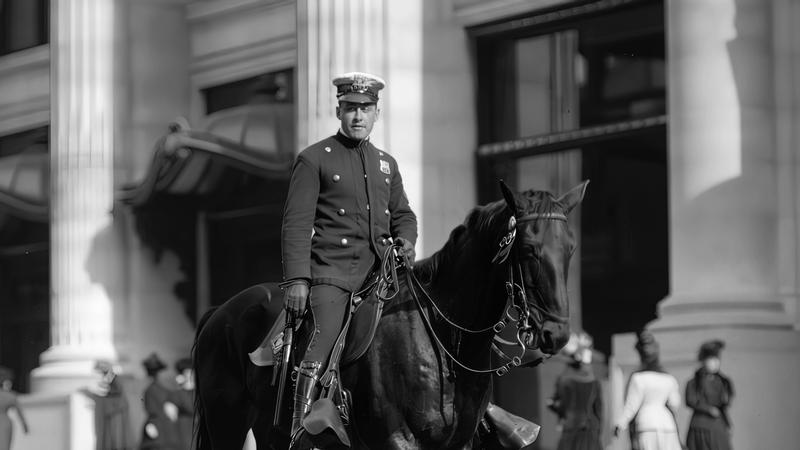

( Courtesy of the Library of Congress - Public Domain )

Announcer: Listener supported WNYC studios.

[music]

Arun Venugopal: This is All Of It. I'm Arun Venugopal in for Allison Stewart. Thanks for spending part of your day with us. Coming up on today's show, we'll preview this weekend's hip-hop anniversary concert at Yankee Stadium with DJ Kid Capri. The Montclair Jazz Festival is also happening, and we'll tell you what's coming up with organizers, Melissa Walker and Christian McBride. We'll be joined by the editor-in-chief of Real Simple for some decluttering 101, and we're going to talk about the new book, The Art Thief, with author Michael Finkel. That's the plan. Let's get started with the new documentary, The Sound of the Police.

KRS-One: Woop-woop! That's the sound of da police!

Woop-woop! That's the sound of the beast!

Woop-woop! That's the sound of da police!

Woop-woop! That's the sound of the beast!

Woop-woop! That's the sound of da police!

Arun Venugopal: That's The Sound of da Police from KRS-One and a new documentary about the history of policing in this country that borrows its title from the song. Sound of the Police connects today's reality of police brutality against Black communities with the early history of policing, such as the slave patrols that monitored and disciplined slave populations, and the infamous Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that terrorized Black people living in the north. We also learn about how police departments handled acts of mass white mob violence, for example, during the red summer of 1919, and public lynchings that occurred in which the police were unresponsive.

Even here in our own city, the film looks back at the history of police unions and how they became so strong with one example being the police riot in 1992 against New York City's first Black mayor, David Dinkins, for his plan to create a civilian complaint review board, CCRB, for the NYPD. All that history can still be felt in the distrust many Black people in this country have towards the police, and also how Black parents have to approach the subject with their kids. Sound of the Police begins streaming on Hulu tomorrow, and with me now is the films director Stanley Nelson, and co-director Valerie Scoon. Hi, Stanley, and hi, Valerie.

Stanley Nelson: Hi, how are you?

Valerie Scoon: Hello.

Arun Venugopal: Let's talk first, Stanley, about what the character that you open up, rather, a person that you start with starts in Minneapolis. A lot of us might associate this with George Floyd and his murder, but you focus on a different incident. That's the 2022 death of Amir Locke and the scene of his funeral. Why start here?

Stanley Nelson: When we first started the film, one of the ideas was that we would start the historical research, but that something would happen within the nine months or so that it would take to make the film. Amir Locke was murdered in Minneapolis. One of the reasons why we also focused on there was that there was so much concern, rightly so, it turns out with Minneapolis and the Minneapolis police. We wanted to work on a case that was developing, and the murder of Amir Locke was a case that was just breaking. We could go to his funeral, we could talk to his newly grieving parents, and so that frames the film.

Arun Venugopal: Tell me a little more about this incident and about this young man.

Stanley Nelson: Amir Locke was a young man in his 20s. He was home in his bed sleeping and the police broke in with what's called a no-knock warrant. One of the amazing things is they had a body cam, and I guess they got the key from the super. You see them sneaking the key in the lock and not making any noise and opening the door. Amir Locke was a licensed gun holder, and he did have a gun but he did not point the gun at the police. He did not have his finger on the trigger. Within nine seconds he's killed by the police. They just opened fire.

Arun Venugopal: We see in this footage that you play, I think a few times during the film, replayed this scene. You slow it down. We see that he's on his sofa in his living room undercovers like a bedsheet or a comforter. Am I right?

Stanley Nelson: He's in bed.

Arun Venugopal: Hot it.

Stanley Nelson: He's in bed asleep.

Arun Venugopal: Got it.

Stanley Nelson: The police with a botched no-knock warrant break into his house and immediately kill him.

Arun Venugopal: What were the elements of this incident that you thought were really important to present to us, Valerie?

Valerie Scoon: I think it was important to show that it happens, that this problem in policing happens not just when people are walking down the street or it's an unusual situation that people may not think a lot about. Do you know what I mean? I think that there's been a problem with no-knocks, which I think Minneapolis has been focused on changing. I think it was partly timing of when it happened and partly the fact that it gives us an unusual look at a licensed gun owner. We often don't see African Americans put in that position of being licensed.

I remember some commentary after he was killed where a licensed gun owner said, "Actually when you wake me up like that, I would reach for my gun as well." I think that offered a perspective on African Americans as being gun owners, as licensed gun owners but in this situation, he wasn't able to survive it because of the way they came in with the no-knocks.

Arun Venugopal: You spent some time with the parents of Amir Locke, and they give us a window into who this young man was. What should we know about him, What stays with you?

Stanley Nelson: They talk about how he was just coming into his own. He was developing as a human being. His father talked about him as being a philosopher and he looked at things very philosophically. We try to give an idea of, again, that he's a human being. I think that we were lucky that his parents were so able to talk about it. Really, you can feel their pain and you feel, that he's a human being that his life was snuffed out and that's what we want to say.

Arun Venugopal: One thing you point out is that so often people who are killed by the police are immediately demonized, are painted as in somehow being complicit in their own death. How was that the case in this particular instance?

Valerie Scoon: I think at the beginning, Amir actually might've been visiting a cousin and sleeping on the couch, that's why you see him on the couch or a relative, I'm not sure. At any rate, I think in the beginning, I remember an expert or one of our interviewees telling me that I think they may have listed him as a suspect in the beginning. They corrected it, but that remains in people's minds whereas really he has no record at all. He wasn't the person the police were looking for. I think in that sense, you have to work against that first impression that was put out there.

Arun Venugopal: We start in the relative present, we go back to your starting point for this in terms of the film, this larger history of slave patrols. Tell me a little about these, where they started, and why they're relevant to us today.

Stanley Nelson: One thing that most people don't understand is that the modern-day police started as slave patrols in 1704, I think is what we say in the Carolinas. They were deputized to keep Black people in line, to make sure that if you were off a plantation, you had a pass and they were just random people that were deputized to do this. That's the start of the police in this country. We don't understand that the police did not always exist. There were no police, but they came out of slave patrols.

Arun Venugopal: You also talk about how the average person, as this institution grew and evolved, that it implicated not just people who were deputized, but just average white people who, I guess, they were incentivized, weren't they, Valerie?

Valerie Scoon: Yes, I think that the system of slavery entails the society to keep it going and for that society's benefit. I think that the idea of being mindful of whether an enslaved person was where they should be, there was always, as historians tell me, a lot of fear of revolt on the part of the enslaved people. They were ever mindful of that in the south, the slave patrols, obviously where they developed.

Stanley Nelson: Also, when the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, it then required people in the North to report any suspicious Black person for the police to be vigilant and be part of the slave catchers Northern Police. We quote from a poster that was issued in Boston where it warned African Americans, "Don't talk to the police. They are not your friends. They will act as slave catchers." That was in Boston in the 1850s. The fraught history of African Americans and the police goes back a long, long way.

Arun Venugopal: One striking fact to me was just how much of the newspaper business, I guess, was funded by ads for fugitive formerly enslaved men and women. This was not just a here and there. This is really a very common occurrence in terms of people in South slave owners looking for their "property," isn't it, Valerie?

Valerie Scoon: Yes. I think it was a widespread, and as you say, profitable business, looking for the enslaved people. I think that one of the things I also or we also learned when we were working on the documentary was what an effort of free Black communities that existed would make to support an enslaved person or sometimes a free Black person would be accused of being an enslaved person, and on the say-so of a white person, they could be sent to slavery. That was true for 12 Years a Slave for Solomon Northrop.

There was an effort made as free Blacks to champion the people who were accused and sent back, but they had little power as well. I think that it was a strong business. I think the connection to the northern law enforcement to legally have to support the slave catchers was also made America, or make the nowhere safe for an enslaved person to be, or for a Black person since you could be accused of being a slave.

Stanley Nelson: The fugutive of slave ads are so prevalent that they were the main source of independent ad revenue for papers across the US. There's a database of over 30,000 ads for runaway slaves. It was a common practice if you think about enslavement, yes, you're going to try to get out of it. There was a common practice to escape, and there was a common and profitable practice to hunt these enslaved people down.

Arun Venugopal: If we've been I guess taught this idea that the South and the North were just two separate entities, but in many ways, there was this I guess codependency, if that's the right word, between people in the North who are profiting from the attempts to recapture formerly enslaved people, isn't it?

Stanley Nelson: One of the things that I've always thought is that it's the original sin of the United States that the United States was formed and it's like the North will not have enslavement, but the South will. To do that, to be a divided country, you have to avoid confrontation. As the South will do what they do, which is enslave people, and the North will ignore it. After the Fugitive Slave Act, it meant that the North was also responsible. Law enforcement in the North was also responsible for enslaving people and suspecting any African-American could be suspected as a fugitive slave and could then be jailed or sent down south because some never had been down south.

Arun Venugopal: Or even if you don't actually have reason to suspect just the idea that it's hanging over and that you can impose that fear is, it's a great way to, I guess, emphasize your power over a population, isn't it? Even if you're in New York City or Baltimore or Boston.

Stanley Nelson: We make the point, I think in the film is that it's very similar to Karen's what we call Karen's today. Is that it's very similar to saying, "I don't like what you're doing. You're a little suspicious, and I'm going to call my police on you." That's the same in 1850 as it is in 2023.

Arun Venugopal: There's a word that's come into wide usage in the last few years, Karen's. You show this a montage of white women who are caught on video, these videos that go viral, calling the cops with this great deal of alarm ostensibly for no legitimate reason, except for the fact that they can call the cops on whoever's holding the phone camera in this case, usually a Black man. Is this something that in your experience of going through all this footage and all that is actually a gendered thing, that it tends to be more often white women who are invoking this power? Is it just that you happen to choose these particular clips of white people, all of whom happen to be women?

Stanley Nelson: I would guess that it is a gender thing that males would exert their power in a different way, in a much more physical way. With Karen's, it's kind of, "I'm going to call my police on you, and when they come, you know it won't be good for you, Black person. That you'll be in trouble because the police will side with me."

Arun Venugopal: Of those different clips that use, one of them is someone that a lot of New Yorkers will be familiar with, which is, I guess her name is Amy Cooper, who basically uses power against a birding enthusiast, in Central Park, right?

Valerie Scoon: Yes, that's right. That's a super clear example in the sense that we see her making up a story, exaggerating the story, and landing on the pressure point of saying a Black man is threatening me, which is the fear from, it feels like an echo of the fear of the slave patrol area. A Black person is threatening me, although we can all see visually that's not happening. Yet, she's calling upon this reflexive fear that's threaded throughout our history from the slave patrols.

Stanley Nelson: I think what was so surprising to us is that it really is a thing. We were able to do a montage of different clips of different women calling the police to come get this Black person. In every case, you see that the Black person isn't doing anything. It's just a matter of "I want you to do this, and you're not doing what I say to do, and I'm going to get my police to make you do what I want you to do."

Arun Venugopal: Are there repercussions for people, either in this case or in others, or have you generally seen that they just go about their lives after the fear has died down?

Stanley Nelson: I think generally they just go about their lives. In the case of the birder, it was so obvious that there were repercussions there. Also because she's mistreating her dog at the same time [laughs] that she's doing this.

Valerie Scoon: There was one story, the gentleman who's watering the garden for his neighbors. There is actually repercussions sometimes, after that. He did explain that he was a pastor, lived across the street, and it was odd because even when the neighbor, the woman who had called the police came out, she recognized him finally and was like, "Oh, yeah." They still arrested him because-

Arun Venugopal: He's just sprinkling his plants out, he is watering his plants out in front-

Valerie Scoon: His neighbor's plants, you know what I mean?

Arun Venugopal: Exactly.

Valerie Scoon: He's like, "I live across the street." They wanted him to get his ID. He's like, "I'm not doing anything wrong. I'm just watering the plants." Then when the neighbor who called came out and saw him, she's like, "Oh, yeah, that is the guy who lives across the street," and yet they still arrested him. When you asked if repercussions, now he has an arrest on his record, and now he has to hire a lawyer, and now he has to get that off and it can hurt your employment to be going back and forth and even to have that. There are repercussions when you're literally arrested.

Arun Venugopal: I want to play a clip from the movie. One of the things you focus on is the elevation, if you will deification of police officers in our white or pop culture and all the TV cop shows that exist. Let's listen to a clip from the film. The first voice we hear is David Simon, the creator of The Wire.

David Simon: One of the most fundamental American filmic forms, cinematic forms is the Western. The idea of the wild frontier and the lone warrior who goes and tames it for civilization.

Speaker 1: Gunsmoke.

David Simon: We don't have a frontier anymore, and yet we do.

Speaker 1: Before us a sprawling city at night stretching far into the horizon.

David Simon: We have our urban reality.

Speaker 1: Here in this melting pot of mixed emotions and fears, a war takes place every moment of the day and night. A war between the criminal and law enforcer. A desperate struggle to maintain peace during the growing years.

David Simon: In the imagination of a lot of American viewers, the police, the thin blue line, are the people who are establishing order, locking up the correct people, and they're trying to, in some way, restore and retain civilization.

Speaker 2: When we see depictions of police in popular culture, they're portrayed as heroes, people who are primarily there to protect us.

Speaker 3: These are programs that make the law enforcement person a kind of embodiment of virtue. That gets transposed onto what we think of as policing in general.

Arun Venugopal: Stanley, the timing of this genre, it's not just coincidental. When do we see that these TV shows and I guess films also that really paint a particular picture of police officers. Is it something a political backdrop that you think is important for people to realize?

Stanely Nelson: No. I think that we see that this has been going on forever since Dragnet in the beginning of TV. It's constant. It's one of the things that's underlying the clips that you hear just now is titles, like 50 titles of different police shows, cop shows. If you turn on your TV now, it seems like there's 10 Law and Orders, and there's just cop shows, cop shows, cop shows. Always in the cop shows, the cops are virtuous. The cops are at least trying to do their best to protect all the citizens. It goes from the ridiculousness of the clip we play from Dragnet to all the way to today, and there are more and more cop shows. I don't think it really rises and falls with any particular political agenda.

After George Floyd, we're in the post-George Floyd period of time, and there's more cop shows on now than ever, it seems. That's where we get so much of our opinion of the police, through the cop shows. We have much more contact, most people do with cop shows than they do with real-life cops.

Arun Venugopal: Two, three years after the protests that followed the killing of George Floyd, is there anything that you think did legitimately get advanced in terms of protections or a wider acknowledgment of the systemic injustice that happens across communities?

Stanely Nelson: I think that now we know, and I think that that's for so many people, especially so many White folks, they now see the police in a different way. I don't think the police have changed that much, but I think that's the start to recognize that there's a problem with the police. I think the recognition of who the police are and who the police are vis-a-vis the African-American community is very different now, or somewhat different now, than it was before George Floyd.

Arun Venugopal: Anything to add, Valerie?

Valerie Scoon: I think that there is much more recognition. I think when I would bring up what I was working on, and I'd say looking at the history of Black people in law enforcement, everybody, no matter what their race was, would say, oh, yes, yes, yes. I would like to know more. They would say, I would like to know more why this is happening. I think that's what we were trying to do with this documentary, is to look at the history of how we got here so that we could have better solutions for both people of color, communities of color as well as for law enforcement themselves to have it's better for all.

Arun Venugopal: I've been speaking to Stanley Nelson and Valerie Scoon about the film they co-directed. It's called Sound of the Police. It begins streaming on tomorrow. Stanley and Valerie, thanks so much for joining you today.

Stanely Nelson: Thank you.

Valerie Scoon: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.